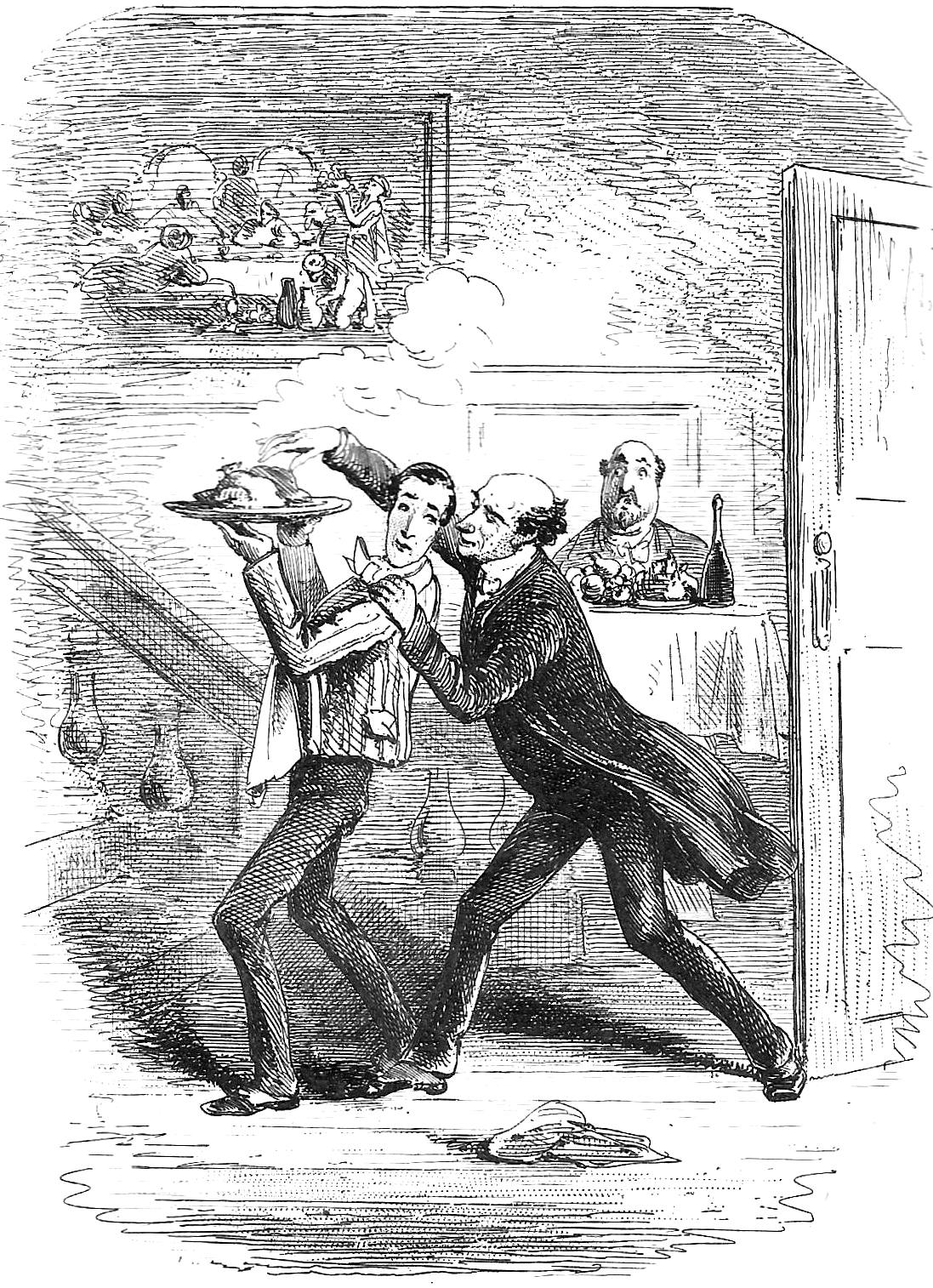

The Rev. Paul foraging

Phiz

Dalziel

February 1858

Steel-engraving

12.3 cm high by 9 cm wide, vignetted

Twenty-fifth regular monthly illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day, facing 251 (1859 edition) in Chapter XLVIII.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: Remaining an unwelcome Guest at "The Golden Hook"

“I heard some noise outside there this morning, Carl,” said[ Grog Davis] to the waiter; “what was the meaning of it?” For a moment or two the waiter hesitated to explain; but after a little went on to speak of a stranger who had been a resident of the inn for some months back without ever paying his bill; the law, singularly enough, not giving the landlord the power of turning him adrift, but simply of ceasing to afford him sustenance, and waiting for some opportunity of his leaving the house to forbid his re-entering it. Davis was much amused at this curious piece of legislation, by which a moneyless guest could be starved out but not expelled, and put many questions as to the stranger, his age, appearance, and nation. All the waiter knew was that he was a venerable-looking man, portly, advanced in life, with specious manners, a soft voice, and a benevolent smile; as to his country, he couldn't guess. He spoke several languages, and his German was, though peculiar, good enough to be a native's.

“But how does he live?” said Davis; “he must eat.”

“There's the puzzle of it!” exclaimed Carl; “for a while he used to watch while I was serving a breakfast or a dinner, and sallying out of his room, which is at the end of the corridor, he'd make off, sometimes with a cutlet, — perhaps a chicken, — now a plate of spinach, now an omelette, till, at last, I never ventured upstairs with the tray without some one to protect it. Not that even this always sufficed, for he was occasionally desperate, and actually seized a dish by force.” [Chapter XLVIII, "A Village Near the Rhine," 387]

Commentary: A Slippery Character from Davis's School Days

Lever emphasizes the picturesque setting of the chapter — that is, the little, out-of-way German village of Holbach, about fifteen miles inland from the Rhine where Grog Davis has been hiding from the authorities after shooting an English officer in a dual outside Brussels. He has been staying as the premier client at the comfortable "Golden Hook," the aptly-named resort of trout fishermen: "it was easy of access, secret, and cheap" (385); however, "it was the calm seclusion, the perfect isolation, that gratified [Davis] most." Far off the beaten track, the place is ideal for avoiding English tourists, and for Grog to keep fit as he practices his swordsmanship, pistol-shooting, and conversational German. After the scene in which the stranger, an unwelcome guest at the inn who has not paid his bill in months, snatches a cutlet or a bit of chicken from the waiter's tray, Lever explains who the Reverend Paul Classon is, and what his past connection is with Grog (now styling himself "Kit") Davis. In short, remarks Lever, as a result of Classon's disputations with Church of England authorities, "he became dissipated and dissolute, his hireling pen scrupled at nothing" (389). He had been practicing confidence schemes upon the unwary in England for years, when, looking for more fertile ground where he was as yet unknown, "he came abroad" (390). Since quitting England, the Rev. Paul Classon has tried his hand at newspaper correspondence and portrait painting:

“And now for yourself, Classon, what have you been at lately?” said Davis, wishing to change the subject.

“Literature and the arts. I have been contributing to a London weekly, as Crimean correspondent, with occasional letters from the gold diggings. I have been painting portraits for a florin the head, till I have exhausted all the celebrities of the three villages near us. My editor has, I believe, run away, however, and supplies have ceased for some time back.” [390]

Needless to say, since the scallywag has been nowhere near either the Crimea or the California gold-fields, his on-the-spot reportage, like his other activities, is merely part of yet another of the Reverend Paul's impostures. In the "foraging" (an oblique allusion to the Crimean conflict, perhaps) picture, Phiz contrasts the elevated theme in the background with the Reverend Paul's scandalous behaviour in the foreground.

A Standard Phiz Technique: The Embedded Picture

Phiz has parenthetically commented upon the Reverend Paul's purloining food from the waiter's serving platter through the embedded scene of a biblical or classical feast. However, Phiz does not clarify whether this scene is Belshazzar's Feast by John Martin (1821) or The Last Supper by Leonardo da Vinci (1498) or Domenico Ghirlandaio (1480), or Albrecht Dürer’s large-scale woodcut (1523), or a feast from an entirely different tradition such as The Barmecide Feast from The Arabian Nights or Banquo ghost's appearing to Macbeth. If Phiz intends through the pair of rounded archways to suggest that the picture is a copy of Ghirlandaio's, in which the figure seated on the opposite side of the table is the treacherous Judas, the illustrator may be equating the dissolute clergyman with the betrayer of Christ. Perhaps the precise scene embedded in the illustration is less important than Phiz's using the subject to mock the clergyman's stooping to steal food since the inn's management is attempting to starve the Reverend Paul into leaving: the Lord helps those who help themselves. The bearded guest watches from his table in the dining-room, stunned at the Anglican minister's temerity, as if he too is an embedded picture. Apparently a local law prohibits the management from simply turning the penurious guest out. Thus, at any point, if the management can starve him out, the meal may prove “Paul Classon's last!”

Other Scenes involving "Holy Paul"

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, July 1858 (Part XIII: Chapters XLVIII through LI, 385-416).

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Davenport Dunn

Next

Created 31 July 2019

Last modified 6 July 2020