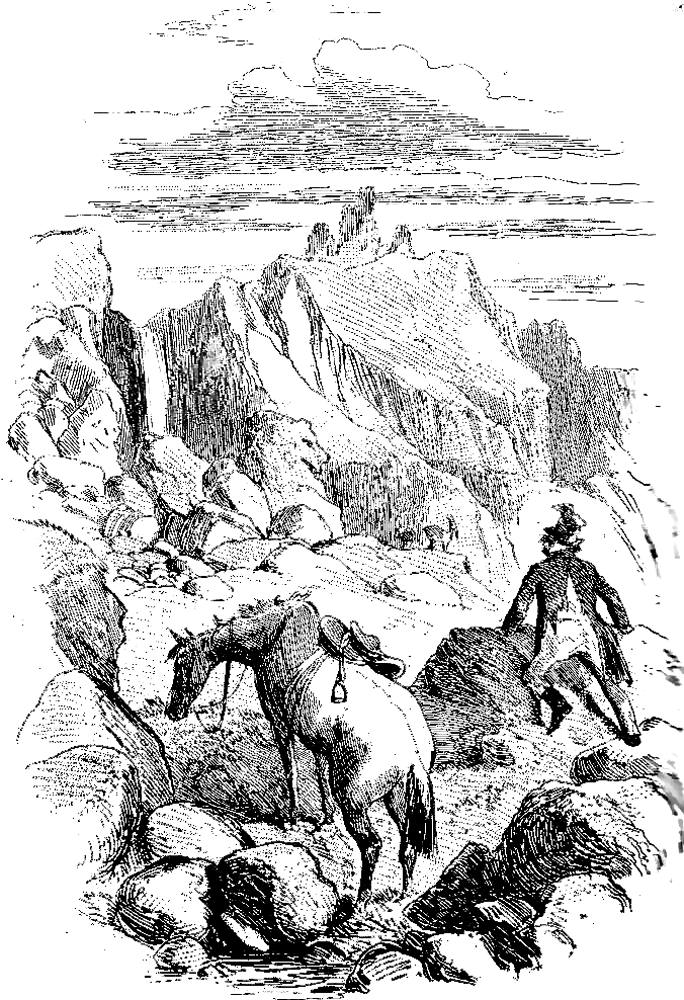

Mr. Hankes in a Fix

Phiz

Dalziel

October 1858

Steel-engraving

14.3 cm (5 ¾ inches) high by 10.2 cm (4 ⅛ inches) wide, vignetted

This illustration originally appeared in the sixteenth monthly (October 1858) instalment for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day, facing page 493.

[Click on image to enlarge it and mouse over text for links.]

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliographical Note

This appeared as the thirty-second serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Steel-plate etching; 14.3 cm (5 ¾ inches) high by 10.2 cm (4 ⅛ inches) wide, vignetted. The story was serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The thirty-third and thirty-fourth illustrations in the volume initially appeared in the reverse order at the very beginning of the sixteenth monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 October 1858. This number included Chapters LVII through LX, and ran from page 481 through 512 to make up the 32-page instalment. This pair of illustrations develops the secondary character of Hankes in a pair of Irish settings.

Passage Illustrated: Lost in the Wilds of Ireland, and Forced to Abandon His Mount

Just possible it is, too, that some curiosity may exist as to what became of Mr. Hankes. Did that great projector of industrial enterprise succeed in retracing his steps with safety? Did he fall in with some one able to guide him back to Glengariff? Did he regain the Hermitage after fatigue and peril, and much self-reproach for an undertaking so foreign to his ways and habits; and did he vow to his own heart that this was to be the last of such excursions on his part? Had he his misgivings, too, that his conduct had not been perfectly heroic; and did he experience a sense of shame in retiring before a peril braved by a young and delicate girl? Admitted to a certain share of that gentleman's confidence, we are obliged to declare that his chief sorrows were occasioned by the loss of time, the amount of inconvenience, and the degree of fatigue the expedition had caused him. It was not till late in the afternoon of the day that he chanced upon a fisherman on his way to Bantry to sell his fish. The poor peasant could not speak nor understand English, and after a vain attempt at explanation on either side, the colloquy ended by Hankes joining company with the man, and proceeding along with him, whither he knew not.

If we have not traced the steps of Sybella's wanderings, we are little disposed to linger along with those of Mr. Hankes, though, if his own account were to be accepted, his journey was a succession of adventures and escapes. Enough if we say that he at last abandoned his horse amid the fissured cliffs of the coast, and, as best he might, clambered over rock and precipice, through tall mazes of wet fern and deep moss, along shingly shores and sandy beaches, till he reached the little inn at Bantry, the weariest and most worn-out of men, his clothes in rags, his shoes in tatters, and he himself scarcely conscious, and utterly indifferent as to what became of him. [Chapter LIX, "The Discovery," pp. 402-403]

Commentary: Satirizing the English Mr. Hankes

Although Lever fails to distinguish between English and Anglo-Irish among his aristocratic characters such as Lady Augusta and Lord Lackington, he emphasizes the Irishness of his protagonists, in particular Sybella and Jack Kellett, whose expert horsemanship seems to be a fundamental aspect of the Irish character. Lever indulges in satirizing Hankes's English ineptitude as a rider — and Phiz, an accomplished horseman himself, seems to be enjoying Hankes's discomfiture. In the previous plate, Mr. Hanks thinks he had better turn back (Chapter 59; also in the October 1858 number), the urbanite, Hankes, who is daunted by the precipitous coastal bridle path, refuses to even attempt to follow the fearless Sybella. In this illustration, following Lever's cue in his many verbal portraits of the Irish coast, Phiz dwarfs Hankes's figure amidst the craggy backdrop, so different, remarks the novelist, from the far less rugged English landscape:

Sybella Kellett was less than just when she said that the country which lay between the Hermitage and Bantry Bay had few claims to the picturesque. It may possibly have been that she spoke with reference to what she fancied might have been Mr. Hankes's judgment of such a scene. There was, indeed, little to please an English eye, — no rich and waving woods, no smiling corn-fields, no expanse of swelling lawn or upland of deep meadow; but there was a wild and grand desolation, a waving surface fissured with deep clefts opening on the sea, which boomed in many a cavern far beneath. There were cliffs upright as a wall, hundreds of feet in height, on whose bare summits some rude remains were still traceable, — the fragment of a church, or shrine, or some lone cross, symbol of a faith that dated from centuries back. Heaths of many a gorgeous hue — purple, golden, and azure-clad a surface ever changing, and ferns that would have overtopped a tall horseman mingled their sprayey leaves with the wild myrtle and the arbutus. [Chapter LVIII, "A Bridle Path," p. 481]

As if to complement Hankes's ragged condition when he finally arrives at the inn at Bantry on the facing page, Phiz indicates that the saddle, cincture, and stirrups on the mount are badly awry. Moreover, even before he undertakes the difficult journey over "the fissured cliffs of the coast" (493), Phiz indicates that the hapless Englishman has split his coat, and damaged both his hat and his trousers. And to connect this illustration with the previous dark plate, Phiz has placed two mountain goats squarely in the middle of the composition. These may be Irish goats (that is, feral goats) or Bilberry Goats; whereas the domestic goats gone wild are common enough in the coastal regions depicted in these illustrations (notably the counties of Mayo, Donegal and Kerry), the Bilberry Goats are actually feral goats who take their name from the chief habitat, the Bilberry Rock in Waterford.

Phiz and Horses

Bibliography

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, October 1858 (Part XVI).

Victorian

Web

Illustra-

tion

Phiz

Davenport Dunn

Next

Last modified 3 August 2019