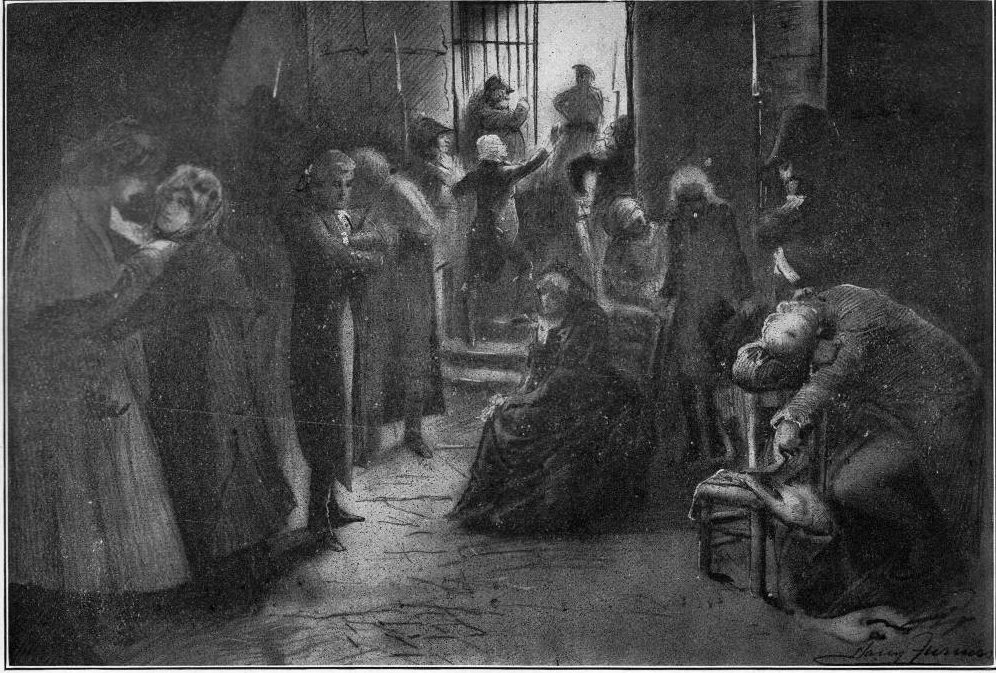

Sydney Carton and the Little Seamstress by Harry Furniss. 1910. Vignetted lithograph, 9.5 cm high x 14.6 cm wide. Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing XIII, 337. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated

"Citizen Evrémonde," she said, touching him with her cold hand. "I am a poor little seamstress, who was with you in La Force."

"He murmured for answer: "True. I forget what you were accused of?"

"Plots. Though the just Heaven knows that I am innocent of any. Is it likely? Who would think of plotting with a poor little weak creature like me?"

"The forlorn smile with which she said it, so touched him, that tears started from his eyes.

"I am not afraid to die, Citizen Evrémonde, but I have done nothing. I am not unwilling to die, if the Republic which is to do so much good to us poor, will profit by my death; but I do not know how that can be, Citizen Evrémonde. Such a poor weak little creature!"

"As the last thing on earth that his heart was to warm and soften to, it warmed and softened to this pitiable girl.

"I heard you were released, Citizen Evrémonde. I hoped it was true?"

"It was. But, I was again taken and condemned."

"If I may ride with you, Citizen Evrémonde, will you let me hold your hand? I am not afraid, but I am little and weak, and it will give me more courage."

"As the patient eyes were lifted to his face, he saw a sudden doubt in them, and then astonishment. He pressed the work-worn, hunger-worn young fingers, and touched his lips. [Book Three, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter Thirteen, "Fifty-Two," 338: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary

The extensive caption which J. A. Hammerton has provided points towards Carton's first crucial test in his impersonation of Charles Darnay since the seamstress had become well acquainted with "Citizen Evrémonde" during his extended incarceration in La Force. Carton carries off his substitution coolly by prompting the young woman to describe the grounds upon which she was arrested, thereby deflecting conversation from himself. She represents a very real source of suspense since she and Darnay could well have been in close association over fourteen months in La Force. That the date is now November 1793 suggests that Carton will shortly become one of the more than two thousand eight-hundred victims of the Reign of Terror executed at the Place de la Concorde between January 1793 and 3 May 1795 (Sanders 164). In the space of just these few lines of dialogue, Dickens uses Darnay's birth-name some five times — as if through this repetition and repeated Carton's reactions to it he may let his mask sli The climax of the dialogue, not in Hammerton's caption for the illustration, is the seamstress's revealing that she, simple as she is, has penetrated Carton's disguise:

"Are you dying for him?" she whispered.

"And his wife and child. Hush! Yes."

"O you will let me hold your brave hand, stranger?"

"Hush! Yes, my poor sister; to the last." [338]

To heighten the suspense, Furniss has placed four armed guards in the darkened communal cell so that, were they not whispering at this point, the conversation between Carton and the seamstress would almost certainly be overheard. In the murky darkness of this general holding cell it is not easy initially for the reader to pick out Carton, but he must be the man to the extreme left, identifiable by the young woman with whom he is in close conversation and by the fact that he — unlike the other male aristocrats in the cell — is not wearing a white-powdered wig (Carton has exchanged a black hair-ribbon with Darnay earlier, and now wears his "Brutus" hairstyle tied back to emphasize his likeness to Darnay).

Since the reader examines the picture proleptically, undoubtedly he or she would revert to it after reading page 338, so that it serves as a suitable complement to the letterpress. The lithograph conveys effectively the atmosphere of despair that grips the prisoners, among whom one is momentarily in the light at the back, apparently waving to somebody. Furniss has not shown all fifty-two people in today's batch consigned to the guillotine, but has selected nine whose postures betoken their emotional responses to the situation. The bayonets glinting in the darkness reveal the presence of five uniformed guards, implying that escape is unlikely. The chiaroscuro is intensified by the presence of just one source of light, which filters through the darkness, highlighting the wigs of the male prisoners and thereby emphasizing their difference from Carton, who, despite the fact that his is the largest figure in the composition, remains muffled in the darkness, his face not detectable in any detail. The picture is rendered more interesting by virtue of the extreme depth of field, by which Furniss positions the reader even further inside the condemned cell and away from the light.

A mere "bit part" in the novel, the seamstress was a named part in the Victorian stage adaptations, a fact that suggests she actually played a significant role in these final scenes, according to Malcolm Morley:

The Only Way was produced at the Lyceum on February 16th, 1899, and the occasion launched [the lead actor] Martin-Harvey as one of the great actor-managers of his day. It was a drama, vital and moving, and his sensitive portrayal of Sydney Carton a creation of romance outstanding in the theatre. . . . . Included in the supporting cast that memorable first night at the Lyceum were Herbert Sleath as Charles Darnay, Holbrook Blinn as Ernest Defarge, Grace Warner as Lucie Manette and the veteran actress, Alice Marriott, a one-time Hamlet, as The Vengeance. Nina de Silva played Mimi, so the anonymous seamstress of the novel was called, and played the part during every one of the ten revivals in the town [i. e., the West End of London], the last being at the Savoy Theatre, November 7th, 1930. [Morley, 39]

Morley's analysis reveals that the celebrated stage adaptation emphasized certain characters that today's novel0-reader would classify as minor, including The Vengeance and the seamstress, diametrical opposites caught up in the swirling tide of Revolution. Almost certainly Furniss would have attended at least one performance of The Only Way prior to his work on the Charles Dickens Library Edition, and therefore may have been influenced by the play in his characterisations of The Vegeance, who appears in a number of his historical "dark" plates, and the seamstress, to whom he has given prominence in this final dark plate.

Furniss's Six Other Darkened Lithographs for Historical Moments in the Novel

- 3. Stopping the Dover Coach, Book the First, "Recalled to Life," Chapter Two, "The Mail," facing 8.

- 21. The Fall of the Bastille, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "Echoing Footsteps," facing 201.

- 22. The End of Foulon, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "The Sea Still Rises," facing 217.

- 24. On the Way to Paris, Book the Third, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter One, "In Secret," facing 232.

- 25. The Grindstone, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 2, "The Grindstone," facing 256.

- 26. The Carmagnole, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 5, "The Wood-Sawyer," facing 265.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions: 1859, 1868, 1874, and 1905

Left: John MacLenan's 26 November 1859 depiction of Carton and the seamstress surrounded by Jacobin militia in "The two stand in the fast-thinning throng of victims". Right: "Sydney Carton and The Seamstress" already on the scaffold in the frontispiece by Sol Eytinge, Junior in the Diamond Edition volume (1868).

Left: Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustration depicting the journey to the place of public execution emphasizes Carton's heroic sacrifice and recently developed relationship with the little seamstress in Book Three, Chapter Fifteen, "The Third Tumbrel" (1874). Right: A. A. Dixon's version of the journey through the streets of Paris to the Place de la Concord in "To the guillotine, all aristocrats" (1905).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987.

Cooper, Fox. The Tale of Two Cities: Or, The Incarcerated Victim of the Bastille. An Historical Drama, in a Prologue and Four Acts. Adapted from Charles Dickens's Story. No. 780. London: Dicks' Standard Plays, n. d.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Hutter, Albert D. "Nation and Generation inA Tale of Two Cities. PMLA 93 (1978): 448-62.

Morley, Malcolm. "The Stage Story of A Tale of Two Cities." The Dickensian, 51 (1954): 34-40.

Robson, Lisa. "The 'Angels' in Dickens's House: Representations of Women in A Tale of Two Cities." Dalhousie Review, no. 3 (Fall 1992): 311-333. Rpt. Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Charles Dickens's "A Tale of Two Cities." New York: InfoBase, 2007, 27-48.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Selznick, David O. (producer). A Tale of Two Cities [black-and-white, soundfilm adaptation of Dickens's novel]. MGM/United Artists, 1935.

Waters, Catherine. "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens and the Politics of Family. Cambridge: Cambridge U. , 1997, 122-49. Rpt. Bloom's Modern Critical Interpretations: Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. NewYork: InfoBase, 2007. 101-128.

Created 3 January 2014

Last modified 12 January 2020