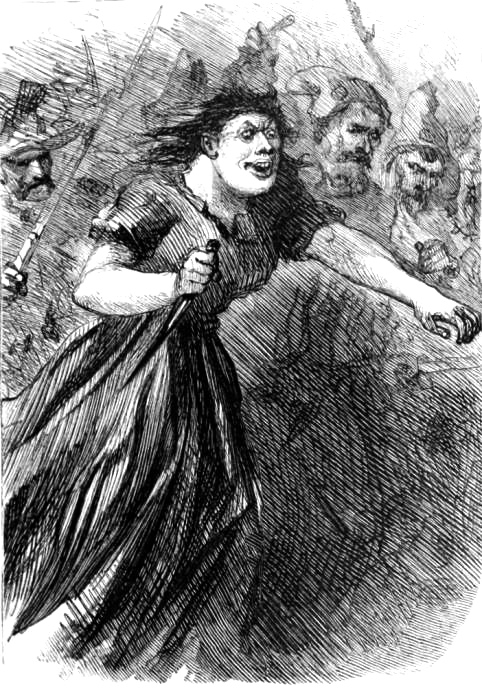

The Carmagnole by Harry Furniss (1910), lithograph, 9.5 cm high by 14.6 cm wide, framed. Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, facing XIII, 265. [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Illustrated: The Carmagnole

. . . presently [Lucie] heard a troubled movement and a shouting coming along, which filled her with fear. A moment afterwards, and a throng of people came pouring round the corner by the prison wall, in the midst of whom was the wood-sawyer hand in hand with The Vengeance. There could not be fewer than five hundred people, and they were dancing like five thousand demons. There was no other music than their own singing. They danced to the popular Revolution song, keeping a ferocious time that was like a gnashing of teeth in unison. Men and women danced together, women danced together, men danced together, as hazard had brought them together. At first, they were a mere storm of coarse red caps and coarse woollen rags; but, as they filled the place, and stopped to dance about Lucie, some ghastly apparition of a dance-figure gone raving mad arose among them. They advanced, retreated, struck at one another's hands, clutched at one another's heads, spun round alone, caught one another and spun round in pairs, until many of them dropped. While those were down, the rest linked hand in hand, and all spun round together: then the ring broke, and in separate rings of two and four they turned and turned until they all stopped at once, began again, struck, clutched, and tore, and then reversed the spin, and all spun round another way. Suddenly they stopped again, paused, struck out the time afresh, formed into lines the width of the public way, and, with their heads low down and their hands high up, swooped screaming off. No fight could have been half so terrible as this dance. It was so emphatically a fallen sport — a something, once innocent, delivered over to all devilry — a healthy pastime changed into a means of angering the blood, bewildering the senses, and steeling the heart. Such grace as was visible in it, made it the uglier, showing how warped and perverted all things good by nature were become. The maidenly bosom bared to this, the pretty almost-child's head thus distracted, the delicate foot mincing in this slough of blood and dirt, were types of the disjointed time.

This was the Carmagnole. [Book Three, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter Five, "The Wood-Sawyer," 264-65: the picture's original caption has been emphasized]

Commentary: A Dark Plate to intensify the Chaos

The caption which J. A. Hammerton has provided does not immediately indicate the timing of this tribal dance by the frenzied denizens of Saint Antoine, but the action of the novel makes it clear that Darnay has now been detained "in secret" for over fourteen months in La Force, and that the date is now November 1793. Although not realised by the initial illustrators of the novel, this sensational street scene had been the subject of a particularly chilling illustration by Fred Barnard in the Household Edition, so that Furniss's lithograph may be based as much on that highly effective illustration in which the savage revellers engulf Lucie as on Thomas Carlyle's description of surrealistic mob action as "a Pyrrhic war-dance" in The French Revolution (2.5.7 and 3.5.4) and on Dickens's description — and quite likely sensational stagings of the peasant dance macabre in fin de si;ècle adaptations of the novel.

The staging of The Carmagnole as a combination of folk dance and opera, perhaps in imitation of Beethoven's revolutionary paean in Fidelio (1805), must have been impressive in the July 1860 three-hour dramatic adaptation by Fox Cooper at the Victoria Theatre, London. It is possible that Furniss saw one of the play's revivals, and in all likelihood the 1899 production of the most celebrated stage adaptation of Dickens's 1859 novel, The Only Way at London's Lyceum Theatre; however, the lithograph of Furniss's pen-and-wash drawing of the chaotic melee bears scant resemblance to the grand chorus of Saint Antoine patriots which opens Act Four in Fox Cooper's melodramatic adaptation, but which both musically and lyrically bears little resemblance to the satirical song and Piedmontese peasant dance as these would have been performed in late autumn, 1793, outside the National Assembly rather in the recently completed public square on the site of the notorious prison:

Scene I. — The Place of the Bastille, during the Festival. In the centre stands a Tree of Liberty, round which a group are dancing the Carmagnole. At a table, R., sit others, drinking, and the rest of the ground is filled up in a moving group of Citizens, Women, and Children.

Chorus. — "The Carmagnole."

The night of iron rule is gone — Around, above, the golden birth Of Freedom, like the light, comes down, And wild as air our joy goes forth, But, brother, if again on France The tyrant's step should dare advance, We'll die the death — we'll die the death! So fear not — cheer thy soul — Come and dance the Carmagnole!

Barsad, Gaspard, Jacques 1, and Vengeance come forward from the Crowd. [IV, i, 15]

Apparently, the dancing of a much wilder Carmagnole was a memorable feature of Tom Taylor's three-act adaptation, which ran through thirty-five performances at the Lyceum in London during the winter of 1860: "the rousing of the sections, and the dancing of the carmagnole, in particular, were replete with wild groupings and individual characteristics (unattributed clipping in The Victoria and Albert Museum, hand-dated 4 February 1860; cited in Bolton, 397).

In contrast to Barnard's crazed masculine adult mob, stripped to the waist, Furniss's mob is generally fully clothed, and contains both a significant number of women as well as several children in the foreground; moreover, from previous dark plates Furniss incorporates a continuing figure, a brawny-armed woman beating a bass drum — The Vengeance. Neither MacLenan nor Phiz in 1859 treated the sensational scene, but Barnard vividly realised it in the Household Edition wood-engraving The Carmagnole (see below). However, unlike Furniss in the present illustration, Barnard has moved in for the closeup, depicting with shocking intensity the manic Sans-culottes abandoning rational control in favour of an atavistic communal rite marked by excessive alcohol consumption and delirium, but without the weapons that characterised the wild scene in which the patriots sharpened their implements in the midst of the September Massacres.

Thus, Furniss has realised yet another historical event in a dark plate, his previous dark plates covering such scenes as The Fall of the Bastille and The End of Foulon, as well as the mob's sharpening its weapons in The Grindstone during the September (1792) Massacres, in which The Vengeance with her bass drum is a continuing figure, a rapacious spirit of the Revolution, although she looks nothing like Eytinge's hideous virago. Thomas Carlyle places this particular dancing of the Carmagnole by a drunken crowd from St. Denis wearing pillaged clerical vestments as occurring as an ironic adjunct to the National Convention of revolutionary leaders on 10 November 1793 at the Festival of Reason and Liberty, still a little early for the snow flurries described by Dickens. The readers of Harper's Weekly did not encounter a realisation of the demonic communal dance to a Provencal tune, but would have imagined MacLenan's street gang engaging in such a dance from the textual description; the American serial reader would likely have connected Dickens's Carmagnole dancers with the illustrator's 5 October 1859 depiction of a roving band of mustachioed toughs as modern-day Gauls in Book Three, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter Six, "Triumph" (see below). In keeping with the textual description, Furniss has stationed two small children in the midst of the savage dance, a detail that Barnard omitted, perhaps because he regarded their presence as inconsistent with his demonic and depraved patriots honing their weapons for another round in the mass execution.

Furniss's Six Other Darkened Lithographs for Historical Moments in the Novel

- 3. Stopping the Dover Coach, Book the First, "Recalled to Life," Chapter Two, "The Mail," facing 8.

- 21. The Fall of the Bastille, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "Echoing Footsteps," facing 201.

- 22. The End of Foulon, Book the Second, "The Golden Thread," Chapter Twenty-two, "The Sea Still Rises," facing 217.

- 24. On the Way to Paris, Book the Third, "The Track of a Storm," Chapter One, "In Secret," facing 232.

- 25. The Grindstone, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 2, "The Grindstone," facing 256.

- 31. Sydney Carton and the little Seamstress, Book the Third, "The Track of the Storm," Chapter 13,"Fifty-Two," facing 337.

Related Materials

- A Tale of Two Cities (1859) — the last Dickens's novel "Phiz" Illustrated

- Costume Notes on A Tale of Two Cities

- List of Plates by Phiz for the 1859 Monthly Instalments

- John McLenan's Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities (1859)

- Sol Eytinge, Jr.'s Diamond Edition Eight Illustrations for A Tale of Two Cities (1867)

- 25 Illustrations for Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities by Fred Barnard (1874)

- A. A. Dixon's Illustrations for the Collins Pocket Edition of A Tale of Two Cities (1905)

Relevant Illustrations from earlier editions: 1859, 1868, 1874, and 1905

Left: McLenan's 5 October 1859 depiction of the mob parading through the streets, holding aloft their grisly trophies, Headnote Vignette for Book Three, Chapter Six, "Triumph". Centre: The Vengeance by Eytinge in the Diamond Edition volume (1868). Right: Dixon's version of the mob arming itself outside Defarge's wine-shop in "Patriots and friends, we are ready" (1905).

Above: Barnard's Household Edition illustration depicting the frenzied mob outside the prison of La Force, in front of the wood sawyer's shop in Book Three, Chapter Three, The Carmagnole (1874).

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. Oxford and New York: Oxford U. , 1988.

Bolton, H. Phili "A Tale of Two Cities." Dickens Dramatized. Boston: G. K. Hall, 1987, 395-412.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens. Ed. Madeline House, Graham Storey, and Kathleen Tillotson. Oxford: Clarendon, 1974. IX (1859-61).

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. All the Year Round. 30 April through 26 November 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by John McLenan. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. 7 May through 3 December 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities and Great Expectations. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr. The Diamond Edition. 16 vols. Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1867.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by Fred Barnard. The Household Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities. Illustrated by A. A. Dixon. London: Collins, 1905.

__________. A Tale of Two Cities, American Notes, and Pictures from Italy. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book Company, 1910. Vol. 13.

Sanders, Andrew. A Companion to "A Tale of Two Cities." London: Unwin Hyman, 1988.

Created 27 December 2013

Last modified 11 January 2020