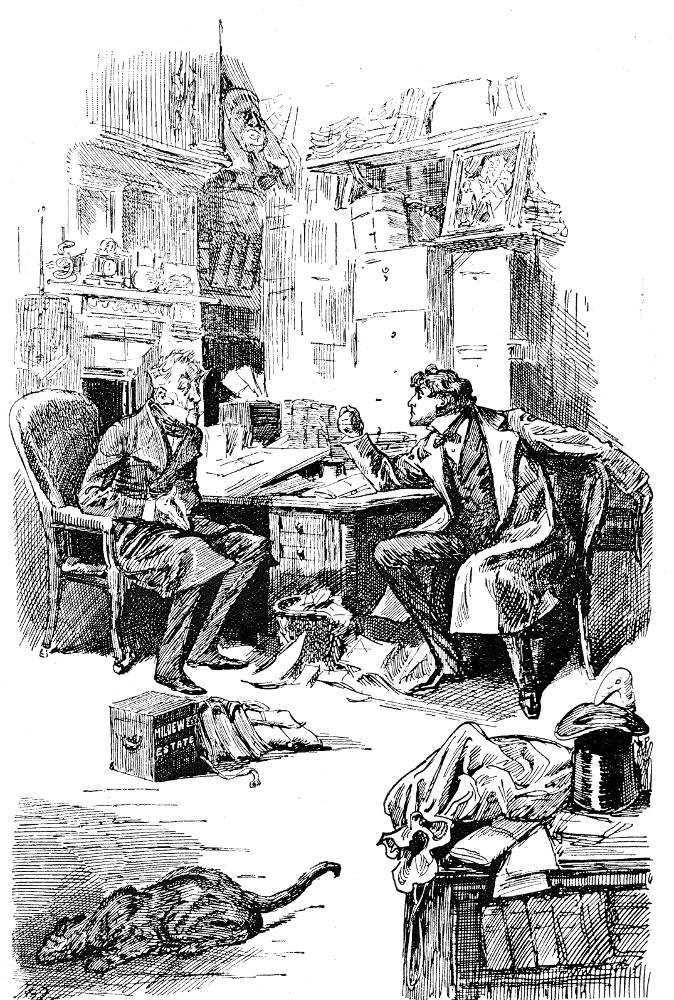

Mr. Woodcourt and Vholes

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 391.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration—> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Bleak House —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Mr. Woodcourt and Vholes

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 391.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

When Mr. Woodcourt arrived in London, he went, that very same day, to Mr. Vholes's in Symond's Inn. For he never once, from the moment when I entreated him to be a friend to Richard, neglected or forgot his promise. He had told me that he accepted the charge as a sacred trust, and he was ever true to it in that spirit.

He found Mr. Vholes in his office and informed Mr. Vholes of his agreement with Richard that he should call there to learn his address.

"Just so, sir," said Mr. Vholes. "Mr. C.'s address is not a hundred miles from here, sir, Mr. C.'s address is not a hundred miles from here. Would you take a seat, sir?"

Mr. Woodcourt thanked Mr. Vholes, but he had no business with him beyond what he had mentioned.

"Just so, sir. I believe, sir," said Mr. Vholes, still quietly insisting on the seat by not giving the address, "that you have influence with Mr. C. Indeed I am aware that you have."

"I was not aware of it myself," returned Mr. Woodcourt; "but I suppose you know best."

"Sir," rejoined Mr. Vholes, self-contained as usual, voice and all, "it is a part of my professional duty to know best. It is a part of my professional duty to study and to understand a gentleman who confides his interests to me. In my professional duty I shall not be wanting, sir, if I know it. I may, with the best intentions, be wanting in it without knowing it; but not if I know it, sir." [Chapter LI, "Enlightened," 391]

Although Dickens does not disparage the intellectual capacity of such lawyers as Tulkinghorn in Bleak House, Jaggers in Great Expectations, and Sydney Carton in A Tale of Two Cities, he is often critical in his portraits of the members of the legal profession (whether barristers or solicitors) in Great Britain. Among his more unflattering portraits are Stryver in TTC and Vholes in BH. Some stories such as David Copperfield feature multiple lawyers, but very rarely does a member of the profession receive unalloyed praise from the writer who as a young man worked in law offices and in 1829 became a court reporter for the Court of Chancery. From the first novel he published, The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, he was highly critical of lawyers such as those two shady operators in the Bardell v. Pickwick breach-of-promise-of-marriage action, Dodson and Fogg, and that shrewd master of realpolitik, the solicitor Mr. Perker. Of the professional cavalcade in his dozen novels, however, attorney Vohles stands out — as the most scurrilous, deceitful, and money-grubbing of Dickens's many lawyers — and certainly one of the most sanctimonious. Even the names "Vohles," "Jaggers," and "Stryver" are hardly suggestive of strong authorial admiration. Dickens introduces Richard Carstone's solicitor in the matter of Jarndyce v. Jarndyce memorably in chapter 37 with some degree of unconscious irony on Skimpole's part:

We asked if that were a friend of Richard's.

"Friend and legal adviser," said Mr. Skimpole. "Now, my dear Miss Summerson, if you want common sense, responsibility, and respectability, all united — if you want an exemplary man — Vholes is the man."

We had not known, we said, that Richard was assisted by any gentleman of that name.

"When he emerged from legal infancy," returned Mr. Skimpole, "he parted from our conversational friend Kenge and took up, I believe, with Vholes. Indeed, I know he did, because I introduced him to Vholes."

"Had you known him long?" asked Ada.

"Vholes? My dear Miss Clare, I had had that kind of acquaintance with him which I have had with several gentlemen of his profession. He had done something or other in a very agreeable, civil manner — taken proceedings, I think, is the expression — which ended in the proceeding of his taking me. Somebody was so good as to step in and pay the money — something and fourpence was the amount; I forget the pounds and shillings, but I know it ended with fourpence, because it struck me at the time as being so odd that I could owe anybody fourpence — and after that I brought them together. Vholes asked me for the introduction, and I gave it. Now I come to think of it," he looked inquiringly at us with his frankest smile as he made the discovery, "Vholes bribed me, perhaps? He gave me something and called it commission. Was it a five-pound note? Do you know, I think it must have been a five-pound note!"

His further consideration of the point was prevented by Richard's coming back to us in an excited state and hastily representing Mr. Vholes—a sallow man with pinched lips that looked as if they were cold, a red eruption here and there upon his face, tall and thin, about fifty years of age, high-shouldered, and stooping. Dressed in black, black-gloved, and buttoned to the chin, there was nothing so remarkable in him as a lifeless manner and a slow, fixed way he had of looking at Richard. [Chapter XXXVII, "Jarndyce and Jarndyce," 302-303]

Left: The initial serial depiction of the lawyer Vholes: Attorney and Client: Fortitude and Impatience (Chapter 39, "Attorney and Client," March 1853). Centre: Fred Barnard's version of the lawyer: "Miss Summerson," said Mr. Vholes, very slowly rubbing his gloved hands, . . . ." This was an ill-advised marriage of Mr. C.'s." (1873): Right: Harry Furniss's dual portrait, but a different pairing: Mr. Vholes and Richard (1910).

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Collins, Philip. Dickens and Crime. London: Macmillan, 1964.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume IV. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XVIII. Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., [1910], 294-338.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Last modified 12 March 2021