Inspector Bucket

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 403.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration—> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Bleak House —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

Inspector Bucket

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.5 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 403.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Mr. Bucket and his fat forefinger are much in consultation together under existing circumstances. When Mr. Bucket has a matter of this pressing interest under his consideration, the fat forefinger seems to rise, to the dignity of a familiar demon. He puts it to his ears, and it whispers information; he puts it to his lips, and it enjoins him to secrecy; he rubs it over his nose, and it sharpens his scent; he shakes it before a guilty man, and it charms him to his destruction. The Augurs of the Detective Temple invariably predict that when Mr. Bucket and that finger are in much conference, a terrible avenger will be heard of before long.

Otherwise mildly studious in his observation of human nature, on the whole a benignant philosopher not disposed to be severe upon the follies of mankind, Mr. Bucket pervades a vast number of houses and strolls about an infinity of streets, to outward appearance rather languishing for want of an object. He is in the friendliest condition towards his species and will drink with most of them. He is free with his money, affable in his manners, innocent in his conversation—but through the placid stream of his life there glides an under-current of forefinger.

Time and place cannot bind Mr. Bucket. Like man in the abstract, he is here to-day and gone to-morrow — but, very unlike man indeed, he is here again the next day. This evening he will be casually looking into the iron extinguishers at the door of Sir Leicester Dedlock's house in town; and to-morrow morning he will be walking on the leads at Chesney Wold, where erst the old man walked whose ghost is propitiated with a hundred guineas. Drawers, desks, pockets, all things belonging to him, Mr. Bucket examines. A few hours afterwards, he and the Roman will be alone together comparing forefingers. [Chapter LIII, "The Track," 403-4]

Mr. Snagsby is dismayed to see, standing with an attentive face between himself and the lawyer at a little distance from the table, a person with a hat and stick in his hand who was not there when he himself came in and has not since entered by the door or by either of the windows. There is a press in the room, but its hinges have not creaked, nor has a step been audible upon the floor. Yet this third person stands there with his attentive face, and his hat and stick in his hands, and his hands behind him, a composed and quiet listener. He is a stoutly built, steady-looking, sharp-eyed man in black, of about the middle-age. Except that he looks at Mr. Snagsby as if he were going to take his portrait, there is nothing remarkable about him at first sight but his ghostly manner of appearing."Don't mind this gentleman," says Mr. Tulkinghorn in his quiet way. "This is only Mr. Bucket." [Chapter XXII, 175]

Eytinge may not have known of the connections between such real-life London detectives as Inspector Field and Jack Whicher of the Metropolitan London Police, but he would likely have been well aware of how Dickens utilized such enigmatic figures as the private investigator Nadgett in Matin Chuzzlewit to solve crimes, and to cast a pall of mystery over the narrative.

All nineteenth-century programs of illustration for Bleak House prominently feature Dickens's dogged criminal investigator, Inspector Bucket, a detective in London's Metropolitan Police charged with investigating the murder of the attorney Tulkinghorn. He is as important as Edgar Allen Poe's Surete detective C. Auguste Dupin, the forerunner of Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes, as he shares honours as the first professional criminal investigator in literature written in English. Dickens seems to have based the character of Detective Bucket on the real-life Scotland Yard investigator Charles Frederick Field (1805-74). The two became associates through Dickens's nocturnal tours of areas of London known to be hotbeds of criminal activity and immorality. In Household Words in its initial year of publication Dickens described his adventures with an "Inspector Wield," a thinly-disguised version of Field, in "A Detective Party" (see Philip Collins, Dickens and Crime, 204-207). Dickens may also have based the character of Inspector Bucket on Jack Whicher, one of the 'original' eight detectives set up in the Detective Branch, founded at Scotland Yard in 1842.

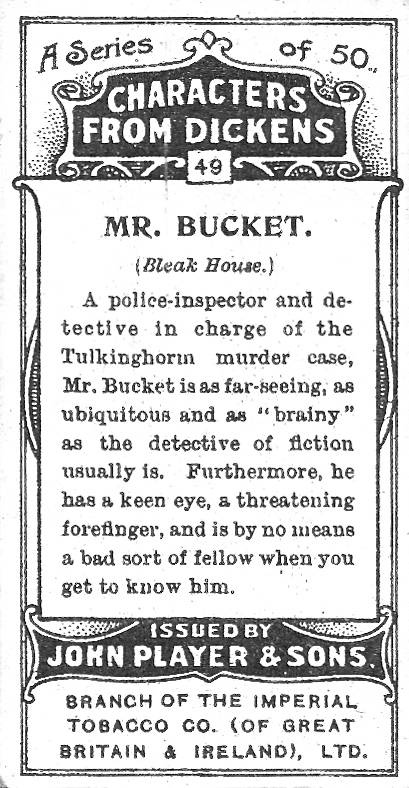

Left: The first appearance of Detective Bucket in Fred Barnard's Household Edition illustrations: "There she is!" cries Jo. (Chapter 22). Centre and right: Kyd's version of the police detective in the Player's Cigarette Card series, Card No. 49: Detective Bucket (1910).

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Collins, Philip. Dickens and Crime. London: Macmillan, 1964.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume IV. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XVIII. Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., [1910], 294-338.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Last modified 28 February 2021