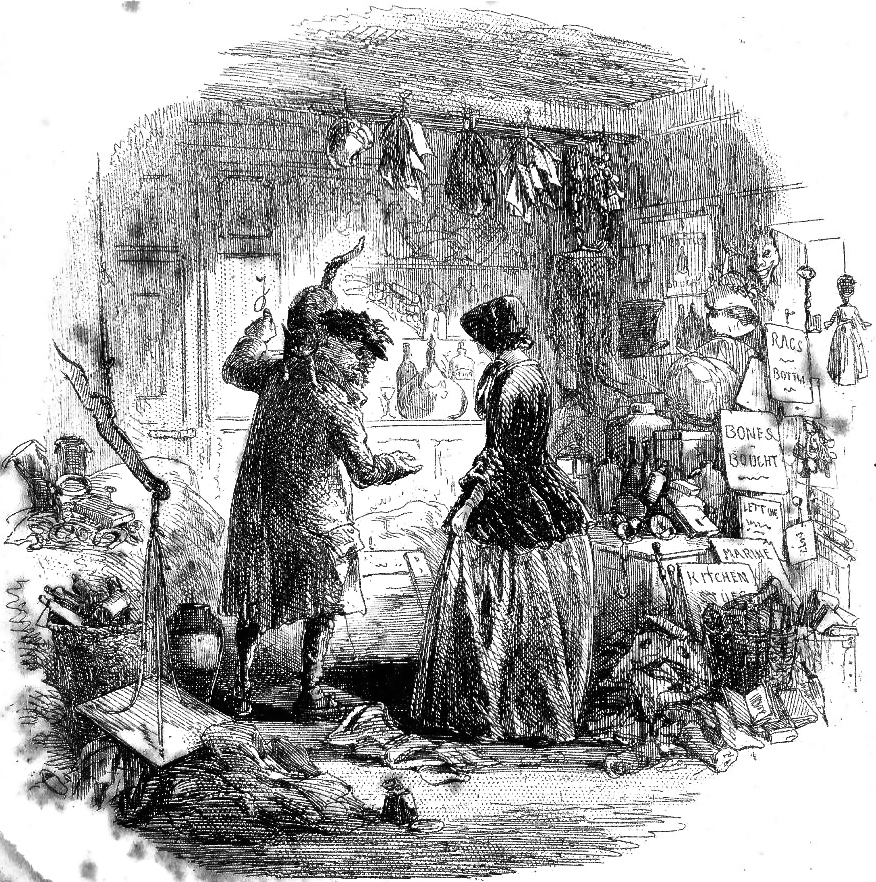

Miss Flite and Krook

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.4 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 29.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[Victorian Web Home —> Visual Arts —> Illustration—> Sol Eytinge, Jr. —> Bleak House —> Charles Dickens —> Next]

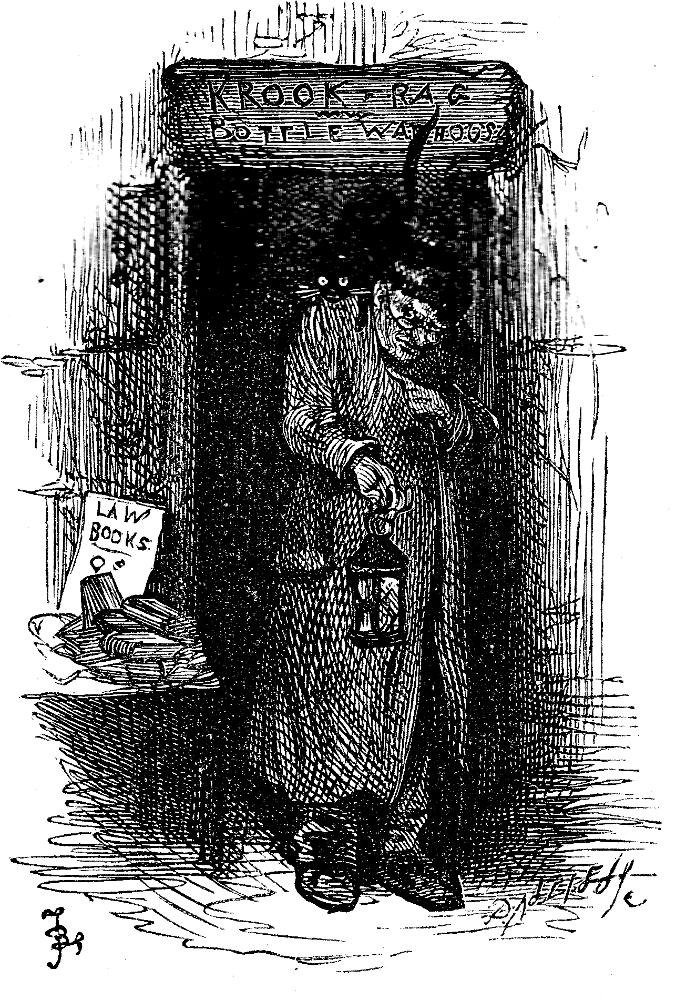

Miss Flite and Krook

Sol Eytinge, Jr.

1867

Wood-engraving

10 x 7.4 cm (framed)

Dickens's Bleak House (Diamond Edition), facing VI, 29.

[Click on image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

"My landlord, Krook," said the little old lady, condescending to him from her lofty station as she presented him to us. "He is called among the neighbours the Lord Chancellor. His shop is called the Court of Chancery. He is a very eccentric person. He is very odd. Oh, I assure you he is very odd!"

She shook her head a great many times and tapped her forehead with her finger to express to us that we must have the goodness to excuse him, "For he is a little — you know —M!" said the old lady with great stateliness. The old man overheard, and laughed.

"It's true enough," he said, going before us with the lantern, "that they call me the Lord Chancellor and call my shop Chancery. And why do you think they call me the Lord Chancellor and my shop Chancery?"

"I don't know, I am sure!" said Richard rather carelessly.

"You see," said the old man, stopping and turning round, "they — Hi! Here's lovely hair! I have got three sacks of ladies' hair below, but none so beautiful and fine as this. What colour, and what texture!"

"That'll do, my good friend!" said Richard, strongly disapproving of his having drawn one of Ada's tresses through his yellow hand. "You can admire as the rest of us do without taking that liberty."

The old man darted at him a sudden look which even called my attention from Ada, who, startled and blushing, was so remarkably beautiful that she seemed to fix the wandering attention of the little old lady herself. But as Ada interposed and laughingly said she could only feel proud of such genuine admiration, Mr. Krook shrunk into his former self as suddenly as he had leaped out of it.

"You see, I have so many things here," he resumed, holding up the lantern, "of so many kinds, and all as the neighbours think (but they know nothing), wasting away and going to rack and ruin, that that's why they have given me and my place a christening. And I have so many old parchmentses and papers in my stock. And I have a liking for rust and must and cobwebs. And all's fish that comes to my net. And I can't abear to part with anything I once lay hold of (or so my neighbours think, but what do THEY know?) or to alter anything, or to have any sweeping, nor scouring, nor cleaning, nor repairing going on about me. That's the way I've got the ill name of Chancery. I don't mind. I go to see my noble and learned brother pretty well every day, when he sits in the Inn. He don't notice me, but I notice him. There's no great odds betwixt us. We both grub on in a muddle. Hi, Lady Jane!" [Chapter 5, "A Morning Adventure," 29-30]

A number of nineteenth-century illustrators depicted the novel's eccentric rag-and-bone recycler who lets rooms to the demented Miss Flite and the opium addict "Nemo," the legal copyist who is in fact Lady Dedlock's lover and the father of Esther Summerson. The most flattering interpretation of Krook is that by Sir John Gilbert, and the most critical that by Furniss. Generously, Gilbert dramatizes Krook as a Prospero-like guide for the young, middle-class visitors to his cavernous emporium; his odd manner of dress, suggesting eighteenth-century male fashion, contrasts the contemporary, "respectable" upper-middle class fashions of his visitors. Like Hablot Knight Browne and Gilbert, Furniss suggests the chaotic nature of Krook's shop by the books, boots, and portmanteaus in the foreground. Whereas Krook appears just as Dickens describes him, "an old man in spectacles and a hairy cap . . . carrying about" (80) a lantern in the Phiz and Gilbert illustrations, Furniss focusses on his crooked figure without providing much background or any sense of whom Krook is directing as he glances nervously over his shoulder at us. His splayed fingers and angular legs support the interpretation that he is decidedly odd, if not insane, thereby supplementing Dickens's description: "he was short, cadaverous, and withered; with his head sideways between his shoulders, and the breath issuing in visible smoke from his mouth, as if he were on fire within. His throat, chin, and eyebrows were so frosted with white hairs, and so gnarled with veins and puckered skin, that he looked from his breast upward, like some old root in a fall of snow" (29).

Left: Phiz's March 1852 engraving of the scene in Krook's depository, The Lord Chancellor Copies from Memory. Centre: Barnard's 1873 wood-engraving of Krook in the doorway of his shop, Title-page Vignette. Right: Gilbert's 1863 frontispiece of Krook leading his young visitors through his shop, A large grey cat leaped from some neighbouring shelf.

Left: Barnard's 1873 Household Edition composite woodblock engraving of the scene in Krook's shop in the fifth chapter, The Lord Chancellor relates the death of Tom Jarndyce, when Krook conducts Caddy, Esther, Ada, and Richard to theupper storey of his rag-and-bottle warehouse. Right: Harry Furniss's 1910 Charles Dickens Library Edition lithograph of Krook's shop, Mr. Krook and His Cat.

Bentley, Nicolas, Michael Slater, and Nina Burgis. The Dickens Index. New York and Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1990.

Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. London: Bradbury and Evans, 1853.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by F. O. C. Darley and John Gilbert. The Works of Charles Dickens. The Household Edition. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1863. Vols. 1-4.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Sol Eytinge, Jr, and engraved by A. V. S. Anthony. 14 vols. Boston: Ticknor & Fields, 1867. VI.

_______. Bleak House, with 61 illustrations by Fred Barnard. Household Edition, volume IV. London: Chapman and Hall, 1873.

_______. Bleak House. Illustrated by Harry Furniss. The Charles Dickens Library Edition. 18 vols. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. XI.

Hammerton, J. A. "Ch. XVIII. Bleak House." The Dickens Picture-Book. London: Educational Book Co., [1910], 294-338.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Chapter 6. "Bleak House and Little Dorrit: Iconography of Darkness." Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington & London: Indiana U. P., 1978. 131-172.

Vann, J. Don. "Bleak House, twenty parts in nineteen monthly instalments, October 1846—April 1848." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: The Modern Language Association, 1985. 69-70./

Last modified 16 February 2021