Photographs, image capture and captions by the author, with added material from the Ormonds' Lord Leighton by George Landow. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them.]

A life so largely spent on foreign soil, and a profession whose object is avowedly the perpetuation of beauty, naturally result in a home full of rare and wonderful things. Our houses are, or ought to be, the outward and manifest sign of ourselves.... [Lang 26]

Exterior

Leighton House (partial view). A Grade II* listed building designed by George Aitchison (1825-1910) for Lord Leighton and built in stages, 1865-95. Suffolk red brick and Caen stone, with a Turkish tiled dome on the Arab Hall to the west, and a distinctive, decoratively bracketed cornice to the house to its west (see listing details). 12 (originally numbered 2) Holland Park Road, London; now the Leighton House Museum.

Left: Arab Hall exterior. Right: Leighton's studio, exterior.

Aitchison has never designed a house when Leighton first commissioned him, and would only ever design one other. His "reputation as an architect was based more on his achievement as a spokesman and theorist than as a practicising architect"; nevertheless, "Leighton's choice of an architect was natural. They had been close friends since 1853, and they shared many ideas in common." As originally designed, it only took two years to build, and was very much a functional studio-house. It "was treated as two distinct units, the front and garden blocks, each with its own roof. The front elevation is surprisingly plain and simple for its period, while the more picturesque garden side, dominated by the studio window [seen above right], suggests a continental source, possibly French" (Ormond 62-63).

Rear view from the back garden.

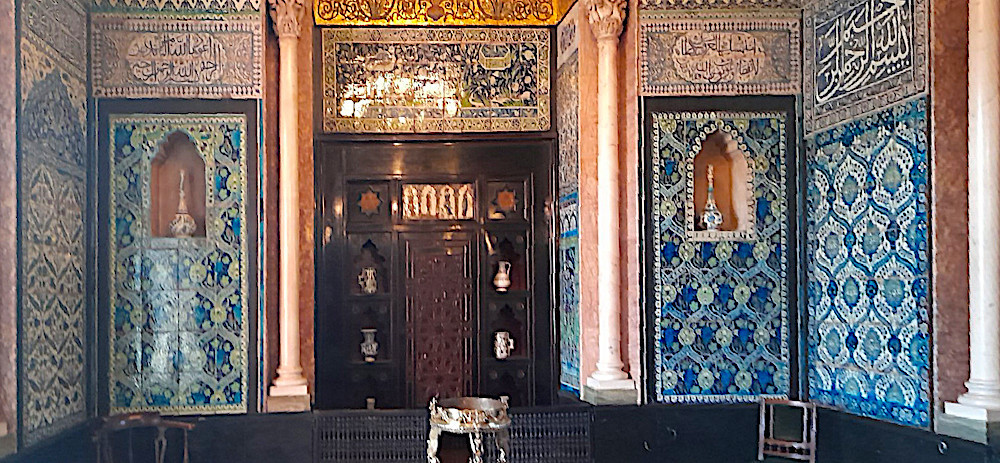

Then, first the studio was enlarged, and a few years later in 1877-81 a "major extension" was built to the west: this was the unique and exotic Arab Hall, inspired by Palace of Zisa in Palermo, and planned as a display case for Leighton's splendid collection of mostly late fifteenth- and early sixteenth-century tiles from Damascus and the Near East, augmented by other tiles given by friends, notably the explorer Sir Richard Burton (see Davies 398, and "History of the House"). Next came the winter studio extension, in brown brick on cast iron columns, to the east. This project kept Aitchison busy for almost three decades.

Interior

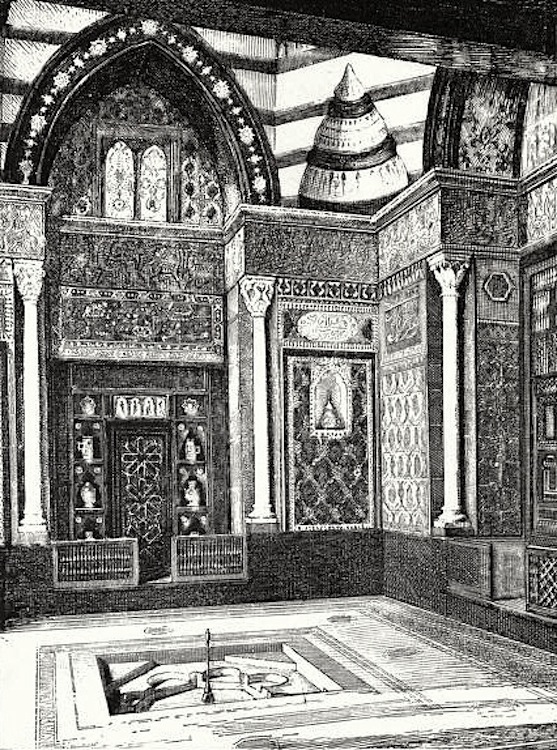

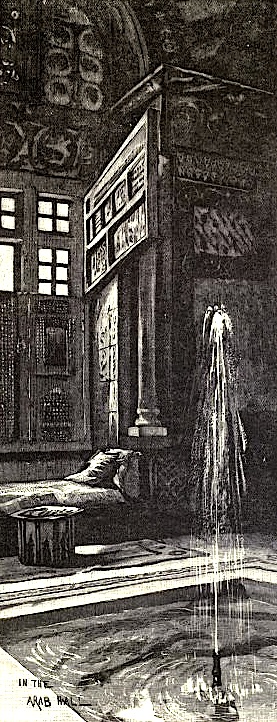

Illustrations from Lang. Left to right: (a) The Staircase, p 26. (b) The Hall, p.27. (c) The Arab Hall, p.28. (d) The Fountain in the Arab Hall, p.29.

Aitchison was Professor of Architecture at the Royal Academy, and President of the Royal Institute of British Architects. But he was most in demand for his interiors. His best work was for rich clients who wanted their homes turned into elegant, aesthetically pleasing settings for their chosen lifestyles. A small but distinctive example of his style can be seen in the light fitments of the New West End Synagogue in Bayswater. His success can be judged by his work at Leighton House. At first the front part of the house consisted of the spacious staircase hall, with the usual amenities, the drawing-room, dining-room and studio all being "in the rear looking out into a deep, shady garden, in which he took great pride," as the American journalist Mary Krout (1851-1927) explained when she visited him there at the end of the Victorian period. "There was a terrace and a fine lawn, with tall, branching trees, many of which, he told me, he had planted with his own hands" (24). Upstairs were just two rooms; Leighton's great painting studio and his surprisingly modest bedroom.

The Arab Hall added at the end of the seventies was symptomatic of the fascination with the Orient at that time, but as unexpected to his turn-of-the-century American visitor as the garden: "there was a dripping fountain playing in a basin of black marble, and carved Moorish grilles before the windows by which the light could be excluded, with cushioned divans beneath them," she reported excitedly; "it was like a bit of Aladdin's palace, which some obliging genius might have set down in London and have forgotten" (Krout 24-25). Now too it might seem eccentric. But, far from being "some self-indulgent exercise in the reuse of architectural antiquities," it was actually designed in order to show off to their best advantage "the work of the leading artists of the time": thus, remarkably, Sir Edgar Joseph Boehm carved the capitals to the smaller columns, Randolph Caldecott was responsible for the "gilded birds on the carved caps of the large columns," Walter Crane made the gilt mosaic frieze in Venice, and "the iridescent cobalt-blue tiles to the staircase and corridor are by William de Morgan" (Davies 398).

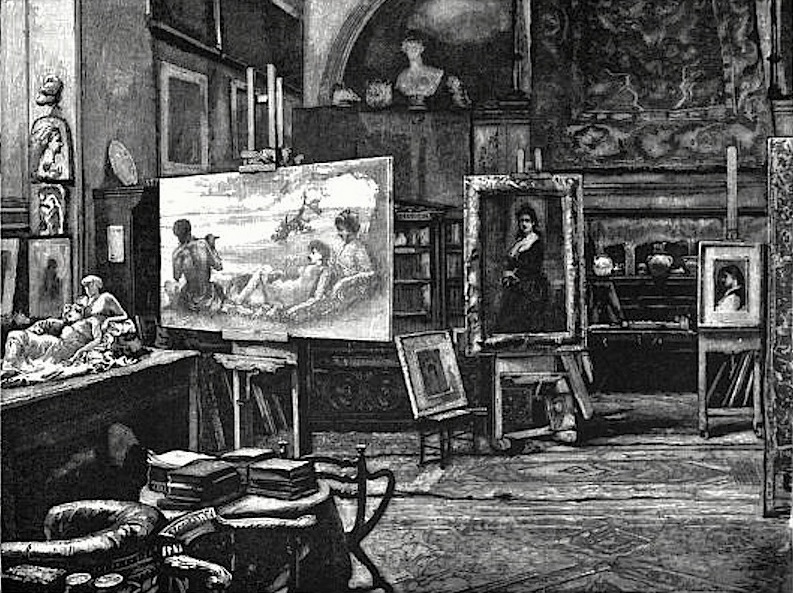

More illustrations from Lang. Left to right: (a) The Studio Window, p. 30. (b) The Studio, p. 31. (c) The Antechamber, p.32.

From the start, the first floor studio window dominated the garden side of the house. Originally, this floor only consisted of a big studio and a small bedroom. But this was followed in 1889 by a winter studio, to enable him to secure "all the light possible from our dull skies." This "delightful" space was filled, according to Krout, with "a bewildering array of treasures, bronzes, marbles, rich fabrics and hangings, furniture of carved oak black as ebony, and plaques from India, China and Japan" (25-26). The last extension, finished only just before Leighton's death, was the Silk Room of 1894-5, which added an exotic touch to the first floor too. This was designed to turn the space previously occupied by a roof terrace into a gallery for Leighton to display paintings by his contemporaries, against a background of green silk. These works, he told Mary Krout, "were painted for this little gallery and given me by my friends — this was from Millais, that from Alma Tadema — this from Burne Jones" — the latter a stately, strutting pea-cock — all admirable examples of the work of each donor" (25).

The antechamber too was by no means an undistinguished nook. Here is a description of it by another visitor, the author and translator Leonora Lang (1851-1933), wife of the folklorist and writer Andrew Lang:

A door at this end of the studio opens into a little antechamber which has a raised divan, looking through a screen of old Cairo wood-work into the Arab hall below. In the centre of this screen is a Persian pot of beautiful design and colour, while the sides of the alcove have panels of blue and white Persian tiles dating mostly from the seventeenth century. This room contains some of the most beautiful pictures in the whole house. — Lang 29

The house that Leighton built with Aitchison over the decades was "for his own artistic delight," wrote his sisters to the Times in late January 1899, when its fate was in the balance. "Every stone of it had been the object of his loving care. It was a joy to him until the moment when he lay down to die" (Orr and Matthews). But he also wanted it to inspire the public, opening it up to them when he was abroad. After his death much was lost, and Martina Droth argued in 2011 that the then partially restored house was still very much a reconstruction, and even obscured the artist's true identity. Comparing it with the illustrations shown above suggests that in fact the main rooms retained a good deal of their original appearance and atmosphere. The 2012 exhibition, "Victorian Visions," which included works by many of those in the Leighton circle, as well as some by Leighton himself, certainly looked very much at home there.

Left: The foot of the staircase (compare with the same view in Lang). Right: Looking into the Arab Hall.

But a more recent and much more ambitious restoration project has produced, as well as greatly improved facilities for visitors at the east end of the house, and extra gallery space there, some previously hidden aspects of it. One is the separate staircase and entrance to Leighton's studio, for use by his models — a matter of normal social convention at that time. Another looks more to the future: after having been boxed in, those stout industrial iron columns which supported the Winter Studio of the late 1880s are now rather proudly on show.

Links to related material

- Uniquely Welcoming: Leighton House Transformed

- Sir Thomas Brock's sculpture, A Moment of Peril, in the garden of Leighton House

- HRH Princess Louise, a bust by Mary Thornycroft on the first floor

- Emilie Isabel Barrington a bust by Mary Thornycroft on the first floor

Bibliography

Dakers, Caroline. The Holland Park Circle: Artists and Victorian Society. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 1999.

Davies, Philip. London: Hidden Interiors. Croxley Green, Herts: Atlantic Publishing, 2012.

Droth, Martina. Journal of Design History 24.4 (2011): 339-58.

"History of the House." Leighton House Museum. Web. 1 June 2014.

Krout, Mary H. A Looker On in London. New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1899. Internet Archive. Uploaded from the Collection of the New York Public Library. Web. 1 June 2014.

Lang, Mrs A. "Sir Frederick Leighton, PRA." In The Life and Work of Sir Frederick Leighton, Bart., President of the Royal Academy, Sir John E. Millais, Bart., Royal Academician, L. Alma Tadema, Royal Academician. London: Art Journal Office, 1886. 1-32. Internet Archive. Uploaded by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 1 June 2014.

Listed Building details for Leighton House. Web. 1 June 2014.

Ormond, Leonée and Richard. Lord Leighton. New Haven: Yale UP, 1975.

Orr, Alexandra, and Augusta N. Matthews. "Lord Leighton's House" (Letters to the Editor) The Times. 28 January 1899: 13. Times Digital Archive. Web. 1 June 2014.

Created 2 June 2014

Updated 16 October 2022