Photographs and image download by the author. You may use these illustrations without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the author and (2) link your document to this URL or cite it in a print document. [Click on the illustrations to enlarge them.]

Exterior

Sandringham House (west front, seen in 2018), largely designed by Albert Jenkins Humbert (1866-70), but with substantial late-nineteenth century extensions, including the right-hand wing, by the architect Colonel Robert William Edis (1839-1927). The estate lies in the parish of Sandringham, Norfolk.

The chief interest of Sandringham House, of course, lies in its connection with the royal family. Lord Palmerston had spotted its potential as a country seat, and the property was then acquired as a "shooting-box" for Prince Edward. When the house already there on the site was demolished, the new one for which it made way was grander, with some influence from Blickling Hall, a Jacobean house in the same county (see Turner).

As for Humbert, he had previously rebuilt St Mildred's, Whippingham for the Prince Consort near Osborne, on the Isle of Wight, and was still engaged in building the royal mausoleum at Frogmore when this project came up. He started with the service wing of Sandringham House in 1866, and completed the main house in 1870. It included a bowling alley like one constructed at Trentham, Staffordshire, by Charles Barry (see listing text), and the stable courtyard (later garages, and now partly a museum). In Jacobean style, with gables, cupolas, a turret and (among post-Humbert additions) stone bay windows, the main part of the house is of brick with Ketton stone dressings (see Pevsner and Wilson 628).

Left: West front in 1893. Source: How, frontispiece. Right: External light with intricate ironwork — possibly executed by Barnard, Bishop & Barnard of Norwich, the firm that made the celebrated Norwich Gates and provided the elaborate lamp standard near St Mildred's church (see Pevsner and Wilson 627).

Edis's extensions were carried out in two phases, in 1881-84 and 1891, on the latter occasion after a fire. His additions were in harmony with the rest, but had their own character — for instance, the large one-storey ballroom he designed to the east of the main entrance frontage in 1883-85 was also Jacobean in style; but it was somewhat livelier, as can be seen in the main photograph above. He also used more brownish-coloured local Norfolk carstone, rather than red brick. Another example of his work was the conservatory (shown below under "Interior," in the image on the right). Very little remains of the original house here, except that a conservatory added to it by Samuel Teulon was turned into a billiard room by Humbert, and some stonework from Teulon's old porch was used in Edis's visitor's entrance.

The east front. Left to right: (a) The east front in 1888. Source: C. Rachel Jones, between pp. 30 and 31. (b) The east front in 2018. (c) The east front in 2018 from the other side.

C. Rachel Jones describes the net result of Humbert and Edis's work succinctly as "a good-looking, red brick house with white stonework, windows of modern form, and a picturesque irregular outline" (21). Others, however, are more critical: "Vaguely historical in appearance, but without scholarly substance, it is pure mid-Victorian with its porte cochere, gables, bay windows, towers, turrets, and tall chimneys, all built in brick with pale Ketton stone details," writes Nigel Jones.

Interior

The Prince and Princess of Wales and Their Family in the Hall of Sandringham House. Penny Illustrated Paper. The royal couple are described on the following page as a "model host and hostess," and there is said to be "no happier home in England" than Sandringham ("The Prince and Princess of Wales," p. 342).

Turning to the interior, Nigel Jones adds that everything in the house "was and still is late Victorian dark abundance, with no surface left undecorated" (249). This comment also sounds negative, but of course such "abundance" as remains makes the interior intensely revealing for interior design historians. What had been preserved by the time these illustrations were made is not an Arts and Crafts showpiece but something more generally representative, if up-market.

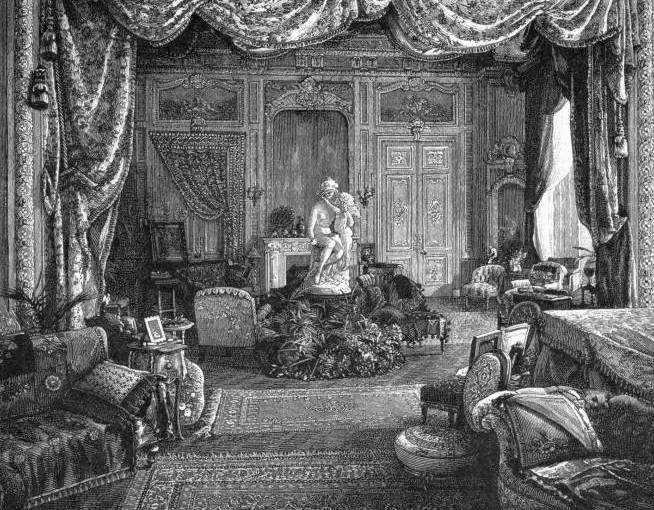

More late Victorian illustrations. Left: The large drawing room. Source: C. Rachel Jones, between pp.58 and 59. Right: The principal conservatory, one of Edis's additions. Source: How 333.

Note especially the staginess of the large drawing room shown on the left above, with its heavy, plush soft-furnishings (the hangings are of "rich chenille," How 332) framing a sculpture of Venus and Cupid in a surround of rocks and plants. A corridor ornamented with armour, swords, antique china, stuffed birds in glass cases, and so on, linked the whole suite of drawing rooms (see How 330). Also on display in the large drawing room, and probably in the rest too, were embroidery pieces, sketches, feather screens and other pieces of handiwork that showed off the skills of the womenfolk. In the late Victorian period, times were yet to change at Sandringham, and the royal household would have been particularly conservative.

The main drawing room opened into the principal conservatory, seen on the right above. This had fancy ironwork in the light-brackets, and an array of the dramatic palms and giant ferns so beloved of the late Victorians. The interior was quite up-to-date in its amenities, with the latest kitchen equipment, and gas lighting: there was an "estate gas plant" (Nigel Jones 250).

Stable and Carriage Complex

Left: The stable blocks round a courtyard (the central building is now the entrance to the Sandringham Museum). Right: Gates, and carriage lodge on the right-hand side of the courtyard.

Grounds

A view across the gardens from the south-west.

The extensive grounds of Sandringham House include the large gardens visible from the west front. Some of the trees are of a considerable age, and two attractive lakes (Upper Lake and Lower Lake) were formed in the 1870s. But according to Nikolaus Pevsner and Bill Wilson, apart from these, the "arrangement" of the gardens dates from the 1860s (628). Within that general scheme, however, as might be expected, the gardens and the wider pleasure grounds have been subject to a process of "continual change and development ... since the late C19 and throughout the C20" (listing text).

Related Material

- Col. R. W. Edis

- The Norwich Gates

- St Mary Magdalene, Sandringham

- "What Was Victorian Taste, Really?"

Bibliography

How, Harry. "The Prince of Wales at Sandringham." Strand Magazine, Vol. 5, No. 28 (April 1893): 327-39. Internet Archive. Web. 13 October 2018.

Jones, C. Rachel (Mrs Herbert). Sandringham, Past and Present. London: Jarrold, 1888. Internet Archive. Web. 13 October 2018.

Jones, Nigel R. Architecture of England, Scotland, and Wales. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood, 2005.

"Sandringham – The Norfolk home of HM the Queen." Country Life. 29 May 2008. Country Life. Web. 24 November 2021.

"The Prince and Princess of Wales at Home in Sandringham." Penny Illustrated Paper. 1 December 1888. Vol. 55, No. 1435: 341-42. Internet Archive. Web. 13 January 2025.

Sandringham House. Historic England. Web. 13 October 2018.

Turner, Michael. "Humbert, Albert Jenkins (1821-1877)." The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 13 October 2018.

Created 13 October 2018

Last modified 13 January 2025