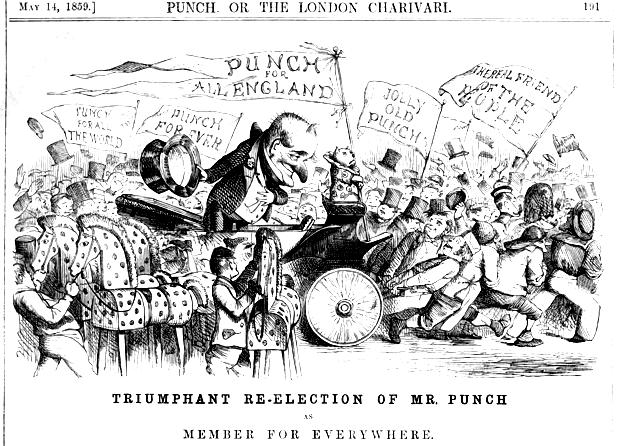

Title pages, left to right: (a) Triumphant Re-election of Mr. Punch — Member for Everywhere (for 14 May 1859). (b) Punch as St. George slaying the Dragon (for Vol. 37, 1859). (c) Punch as Bacchus worshipped by nymphs and at least one drum-playing satyr (for Vol. 50, 1866). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Title and inception

The title of the famous magazine of Victorian humour, Punch, might have been short for Punchinello, adapted from the Neapolitan dialectal "polecenella," a young turkey cock, to the hooked bill of which the hooked nose of Punch's mask in the Commedia del Arte bears some resemblance. But there are other possibilities as well. Favourite among these is the inspiration of the drink, Punch, at the magazine's inception:

Punch was born in the ferment of early Victorian publishing where periodicals quickly appeared (and just as quickly disappeared), produced by a shifting group of journalists, writers, printers and engravers who drank in the same pubs and ate at the same eating houses. Punch was no exception. One such pub was (appropriately enough) the Shakespeare's Head, kept by Punch's future editor, Mark Lemon [1809-1870]. The founders of the new magazine were the wood engraver Ebenezer Landells [1808-1860] and writer Henry Mayhew [1812-1887], along with three other shareholders including Lemon. As for the magazine’s name, the legend went that someone remarked the new paper should be like a good mixture of Punch — nothing without Lemon — to which Mayhew cried: "A capital idea! We’ll call it Punch!" and a prospectus was drawn up announcing "A new work of wit and whim embellished with cuts and caricatures." [Walasek 10]

The printer Joseph Last (c.1809-1880) and the Irish playwright and journalist Sterling Coyne (1803-1868) were the other two shareholders not mentioned here. These men got together a small team of young journalists and artists, among the best known of whom were Douglas Jerrold (1803-1857), William Makepeace Thackeray (1811-1863), John Leech (1817-1864) and Richard Doyle (1824-1883).

One or two such comic papers had already appeared in London in the 1830s, notably Figaro in London (1831-9), edited first by Gilbert Abbott à Beckett, and then by Henry Mayhew, and Punchinello (1832) illustrated by George Cruikshank (1792-1878). Early imitators of Figaro were Mark Lemon's Punch in London and Thomas Hood's annual Comic Offering . Meantime, in Paris, Philippon's Charivari was all the rage. No wonder it had occurred to Landells that a similar illustrated paper might do well in London, and no wonder that Mayhew had taken him up on it — no wonder too that Lemon, already well known as a humorist, journalist, as well as a dramatist, should have gone in with them. Thus the first issue of the illustrated humorous magazine Punch, or the London Charivari appeared on 17 July 1841, at this point a strongly radical publication. It sold well, but not well enough: despite early sales of 6,000 copies a week, the new weekly soon got into difficulties. The fact was that sales of at least 10,000 were needed to cover costs.

Taken over by Bradbury and Evans

Richard Doyle's 1842 cover of Punch. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Owing to these financial difficulties, in December 1842 the printing and publishing firm Bradbury and Evans were persuaded to take over the magazine (see Spielmann 31-36). In these early years the firm made the most of its capital investment in presses and types by printing both Punch and the novels of Dickens and Thackeray — the former abandoned Chapman and Hall for Bradbury and Evans after they failed to secure him £1,000 clear on the publication of A Christmas Carol in December 1843. From then on, Punch's artists were closely associated with the Christmas Books, John Leech being the principal illustrator for each of succeeding four. It was rather like a club: Lemon, Leech, Mayhew, Jerrold, and the humorist Gilbert à Beckett (1811-1856) played alongside Dickens in such amateur productions as Ben Jonson's Every Man in His Humour (1844). They were like minded: with Dickens the Brotherhood shared what were regarded as "radical" sentiments, including cynicism about government and a genuine concern about the welfare of the working poor.

In those days, Punch could be very hard hitting. For example, in 1843 it published Thomas Hood's "The Song of the Shirt," about the lot of the poor seamstress, and Robert Jacob Hammerton's famous cartoon, "Capital and Labour." It campaigned against the Corn Laws and the 1834 Poor Law, and demanded the reform of parliament, supporting Chartism (although not the use of force).

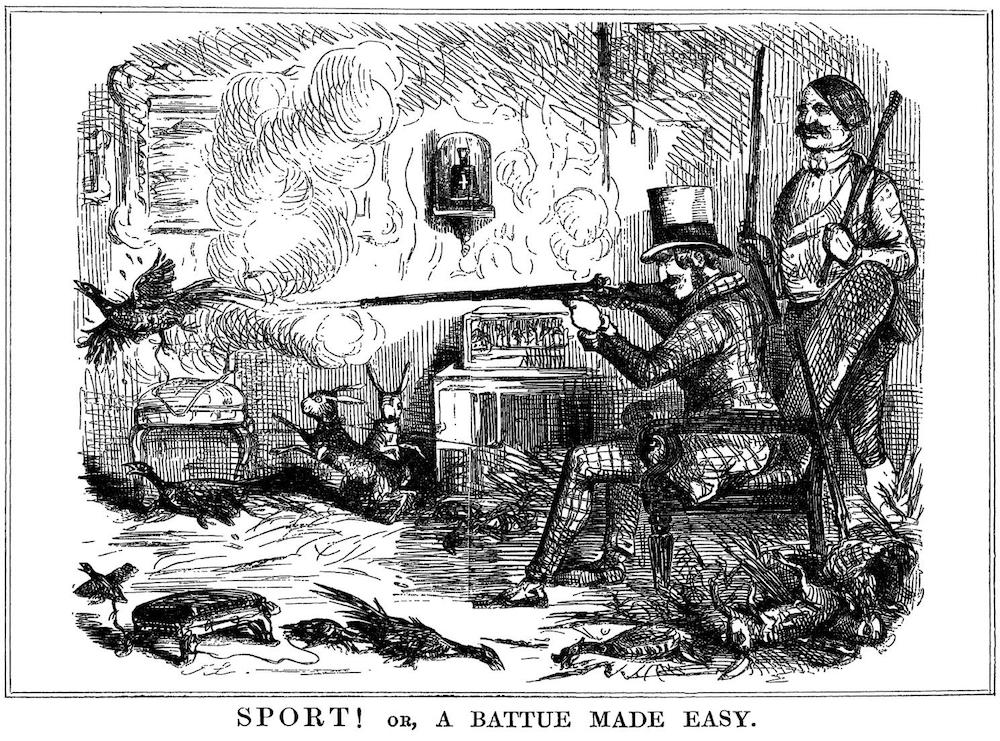

"Sport! Or, A Battue Made Easy" — Prince Albert, nattily dressed and seated indoors in comfort, has been provided with ludicrously easy targets to satisfy his huntsman's instincts. Source, Punch Vol. VIII (1845), following p.58. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

It was also quite common, says Marion Spielmann, to attack individuals such as "Lord Brougham, 'Dizzy,' Lord Aberdeen, and, during his earlier career, John Bright." Spielmann might have mentioned Sir Robert Peel, as well, when he was Prime Minister; and special reference should be made to the magazine's treatment of Prince Albert, a popular butt of its mockery. Nothing about the Prince was safe from snide comment. His attire and his prowess in hunting were both ridiculed (see the cartoon on the right for its take on these), as were his military exercises — consisting, it claimed, of four hours a day practising the telescope (Vol VIII: 115). There was even some sport to be had out of his punctiliousness with regard to his shaving water (Vol. VII: 130).

But, Spielmann continues, the magazine gradually mellowed in outlook over the 1850s:

many things were done forty years ago which nowadays "the Table" would neither tolerate nor excuse — such as certain attacks upon defenceless royalty (more particularly upon Prince Albert) as being both unfair and in bad taste. The courteous highmindedness of Sir John Tenniel has made greatly for this mellowing and moderation, to the point, indeed, that many complain that Punch no longer hits out straight from the shoulder. This peaceable tendency obviously arises from neither fear nor sycophancy, but from an anxious desire to be entirely just and good-natured, and to avoid coarseness or breach of taste. [101]

There were still some social and political campaigns that Lemon supported, such as a reduction in the hours of shopworkers and attacks on the the bungling of the Crimean War. Its satire continued to deal with political subjects, such as the Second Reform Bill (1866-7) and parliamentary debates concerning Irish Home Rule in the 1880s. But after 1850, the magazine began more and more to reflect the conservative views of that the growing portion of the British middle class that were Punch original readership.

New names

"The Mahogany Tree" — the Punch "Brotherhood raise a glass to Mr Punch. Source: Spielmann, frontispiece, from a drawing by Linley Sambourne. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Under Lemon, Punch provided an outlet for comic writers such as Thackeray himself, and the illustrators already mentioned above. But as the years passed, other important names were gradually added to this list: John Tenniel was hired in 1850, when Doyle, a devout Catholic, regretfully resigned because of the magazine's attacks on Roman Catholiism; and the first drawing by Charles Keene (1823-1891) appeared in 1851. He joined the staff in 1860, the year that George Du Maurier (1820-1914) began contributing. Du Maurier joined the staff a few years later, in 1864. These were all noted book illustrators as well. As can be seen, Punch attracted a positive galaxy of talent: other cartoonists working for it during the later part of the nineteenth century included Harry Furniss (1854-1925), Linley Sambourne (1844-1910), and Phil May (1854-1903). To themselves, these constituted "The Punch Brotherhood," although to outsiders they were "those Punch people."

Though comic monthlies, such as William Harrison Ainsworth's Ainsworth's Magazine in the early period (1842-54), and various Christmas annuals appeared, Punch reigned supreme in the category of humorous journals. The only serious threat to it was Fun, which featured the humour of W. S. Gilbert.

After Lemon's death in 1870, the editorship passed to Shirley Brooks (1816-1874); in 1874, he in turn was replaced by a Scot, the radical dramatist Tom Taylor (1817-1880), author of some hundred pieces for the stage, including a protest against the penal system, The Ticket of Leave Man (1863), and, perhaps of more significance to Americans, Our American Cousin (1858), the comedy that President Lincoln was watching on the night of Good Friday, 14 April, 1865, when he was assassinated by John Wilkes Booth at Ford's Theater in Washington, D. C. In 1880, F. C. Burnand (1836-1917) took over from Taylor, his twenty-seven year tenure marking a pronounced decline in the magazine's radical sentiments. The remaining editors were Owen Seamen (1861-1936); E. V. Knox (1881-1971); Cyril Bird, better known by his pen-name "Fougasse" (1887-1965); Malcolm Muggeridge (1903-1990); and Alan Coren (1938-2007).

A national institution

Richard Doyle's 1859 cover of Punch, which was used right up until 1954. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

By Seaman's time, if not before, Punch had become a "National Institution, ... aligned with the upper ranks of society," says Helen Walasek, pointing out that editors Burnand and Seaman were both given knighthoods, as were Tenniel and Bernard Partridge (1861-1945), who were responsible for the most popular political cartoons (12). It continued to be part of the establishment after World War I, when it had the reputation of being "a magazine produced by schoolmasters for schoolmasters" (qtd. in Walasek 12), and it was only with the retirement of editor Alan Coren in 1987 that its popularity declined, until it went out of circulation on 8 April 1992. A few years later, an unsuccessful bid was made to relaunch it and win back an audience, but it finally closed in 2002 (see Walasek 13).

It is sad that this magazine, so distinctive in appearance, content and style, should have left the publishing scene. From 1849 to 1954 it had used the famous cover drawing designed by Doyle, a re-working of his earlier design of 1844, with its "very droll" bas-relief on the base of Punch's platform (Altick 318). This depicts Bacchus in triumphant procession, being crowned by a pair of nymphs as he rides along on a donkey, with cherubs around him (the front one beating a huge drum) and others playing instruments or just skipping along, and a Pan figure bringing up the rear. For over a century, this cover design had adorned the magazine as its familiar wrapper, until, under Muggeridge's brief editorship (1952-57), the journal got a new look and began to sport a different full-colour design each week. However, it usually still featured Punch and his dog, Toby. For another two decades, the original Doyle drawing could be found at the top of the Charivari page, until the "last vestige of Doyle's image disappeared from the inside pages in 1978" (Birch 813). Forty years on, it is still that image which is remembered with nostalgia. — Revised and updated by Jacqueline Banerjee

Related Material

Bibliography

Altick, Richard Daniel. Punch: The Lively Youth of a British Institution. Athens: Ohio University Press, 1997.

Appelbaum, Stanley, and Richard Kelly. Great Drawings and Illustrations from Punch — 192 Works by Leech, Keene, Du Maurier, May & 21 Others, 1840-1901. London: Dover (Constable), 1981. (This has useful short biographies of the artists, including the less familiar ones.)

Birch, Dinah, ed. Oxford Companion to English Literature . 7th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009. 813.

"Gould, Sir Francis Carruthers (1844-1925)." The Political Cartoon Gallery. Web. 4 August 2018.

Phillips, G. "Last, Joseph William (1809?–1880), printer and journal proprietor." Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online Ed. Web. 4 August 2018.

Punch, Vol VII (1844). Internet Archive. Contributed by the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Delhi. Web. 4 August 2018.

Punch, Vol VIII (1845). Internet Archive. Contributed by the Rashtrapati Bhavan, Delhi. Web. 4 August 2018.

Spielmann, M. H. The History of "Punch." London: Cassell, 1895. Internet Archive. Contributed by the University of California. Web. 4 August 2018.

Walasek, Helen. Introduction. The Best of Punch Cartoons: 2000 Humour Classics. New York: Overlook Press, 2008. 8-13.

Last modified 4 August 2018