he

campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws

was led by the Anti-Corn-Law League (ACLL) and was closely modelled on that

of the Catholic Association led by Daniel O'Connell.

The ACLL published pamphlets, employed peripatetic speakers and held public

meetings. They had a very busy headquarters in Manchester where they kept copies

of the electoral registers and produced their propaganda. By 1841 the ACLL had

two MPs: Richard Cobden and John Bright. These men

constantly asked questions concerning the Corn Laws of the new Prime Minister,

Sir Robert Peel.

he

campaign for the repeal of the Corn Laws

was led by the Anti-Corn-Law League (ACLL) and was closely modelled on that

of the Catholic Association led by Daniel O'Connell.

The ACLL published pamphlets, employed peripatetic speakers and held public

meetings. They had a very busy headquarters in Manchester where they kept copies

of the electoral registers and produced their propaganda. By 1841 the ACLL had

two MPs: Richard Cobden and John Bright. These men

constantly asked questions concerning the Corn Laws of the new Prime Minister,

Sir Robert Peel.

Right: A membership card in the Anti-Corn-Law League. Note the banner over the group of praying figures that says "Give us this day our daily bread." Left: Signing an Anti-Corn-Law Petition. [Click on pictures for larger images.]

Between 1841 and 1845 the Anti-Corn-Law League grew into a very powerful political force. It used every opportunity to attack the government; it was winning support for the anti-government and anti-Corn Law groups by registering voters and having candidates in by-elections; it tried to create discontent among the working classes by encouraging factory-owning ACLL members to cut wages and put their workers on short time. As an opposition group, the ACLL threatened Peel's political future.

Peel was in an invidious position. His wealth came from the family's textile mills and was favourable to freer trade but had come to power at the head of a Conservative/Tory government in 1841 on a platform of maintaining the Corn Laws. He believed that many of Britain's ills were the result of a stagnant economy but needed an excuse to move for a repeal of the Corn Laws. As Peel argued. "Something effectual must be done to revive the languishing commerce and manufacturing industry of this country ... We must make this country a cheap country for living."

In the 1842 Budget he tackled the problem of the Corn Laws by implementing a reduced sliding scale. When domestic wheat cost 73/- per quarter, the duty would only be 1/-. Other measures in the budget were

- the introduction of Income Tax at 7d in the £ on incomes over £150 p.a. for a three year period. Peel had wanted to introduce income tax in 1828-30, therefore he picked up the old threads in 1842.

- he reduced tariffs:

(a) raw materials to 5%

(b) semi-manufactured goods to 12%

(c) foreign manufactures to 20%

This sort of legislation won approval in parliament and continued over the next two Budgets.

Anti-CornLaw Meeting in Covent Garden Theatre from the 1843 Illustrated London News. Click on image to enlarge it.

By 1844 Peel was becoming increasingly unpopular among his own back-bench MPs to whom he openly referred as "blockheads". He never consulted them about policy nor told them what he was proposing to do. It was becoming clear that the Tory wing of his party was reluctant to give him the support he demanded. His government survived a vote on factory reform only because he made it a Vote of Confidence and Peel realised that his ministry would not be able to carry on much longer.

The protectionists — men who wanted to retain the Corn Laws — were galled by Peel's change of mind and his "treason" to the party. They felt that he had abandoned the Conservatives and should therefore resign his leadership — or at least call an election. Farmers, especially tenants, were determined to use the franchise to defend protectionism. They formed the Anti-League in 1844, led by the Dukes of Buckingham and Richmond. These men had left the Whigs and joined the Conservatives because they suspected Whig policy on the Corn Laws: this was partly responsible for the 1841 Conservative victory. Agricultural M.P.s were afraid of upsetting their constituents.

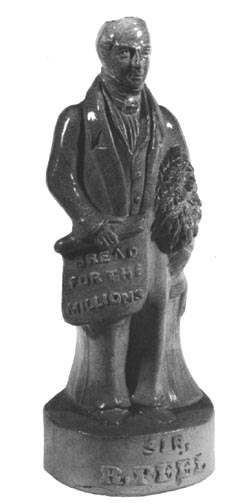

"The repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 whereby restrictive tariffs were removed from British agriculture and the price of bread reduced, was the result of a long and widespread agitation fostered by Anti-Corn Law leagues in all parts of the country. The repeal was marked by the sale of innumerable emblems, among them crude statuettes of the Prime Minister, Sir Robert Peel as well as commemorative china inscribed with words of thanksgiving." — Nicolas Bentley.

In 1845 the beginning of the Irish Potato Famine gave Peel the excuse for which he had been looking. He felt unable to repeal the Corn Laws on purely economic grounds but the crisis in Ireland together with the poor harvests in Britain was an opportunity too good to let pass. Lord John Russell, the leader of the Whigs, already had issued the Edinburgh Letter which encouraged Peel to propose the legislation because he would have the support of the Whigs. The content of the Bill was his decision alone, providing for a gradual reduction over three years. He did this because gradual reduction would create less risk of the failure of the Bill: the ACLL demanded total and immediate repeal and Peel could not be seen to be giving in to extra-parliamentary pressure.

Early in 1846, Peel introduced his proposal to modify the existing Corn Laws. Following two speeches in parliament on 22 and 27 January he was faced with the defection of two-thirds of his party and a bitter argument about his personal political consistence and party leadership. On 15 May he made a speech in which he set out his attitude on the need for and justification of repeal.

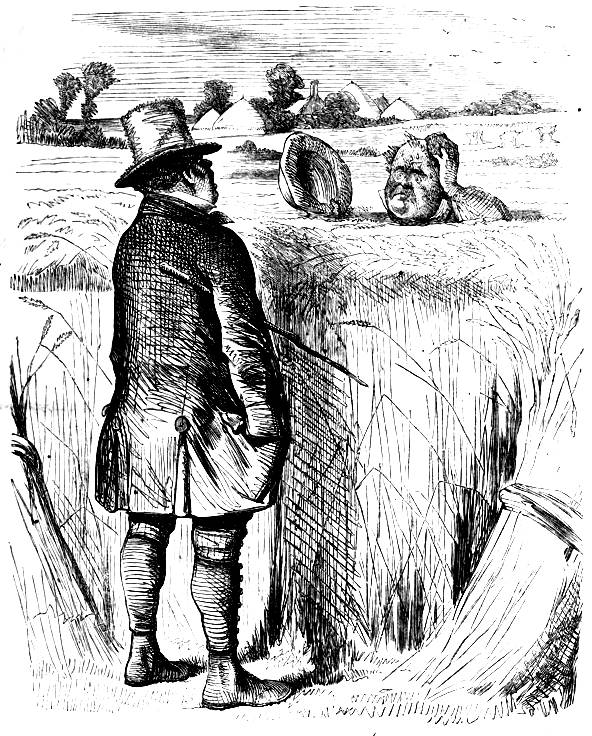

The Weather and the Crops — a farmer or landowner’s view of abundant crops. Click on image to enlarge it and the full caption of the cartoon.

On 15 May 1846 the repeal of the Corn Laws was passed by a combination of Conservatives, Whigs and free traders. Only 112 Conservatives voted for it; 241 voted against it. The Bill's passage through the House of Lords probably demonstrates the military discipline which the Duke of Wellington enforced on that House for its own good.

Repeal was perhaps a concession by the aristocracy; a timely retreat. Common sense saved the upper classes, because other reforms such as the 1867 Reform Act, the 1872 secret ballot and so on, were delayed.

On 26 June 1846 Peel was defeated on an Irish Coercion Bill by a combination of Whigs, Radicals, Irish and protectionists. He resigned immediately after that, rather than ask for a dissolution, to prevent an election becoming a vote of confidence.

Related Web Resources

- Anti-Corn Law poetry: Ebenezer Elliott's The Splendid Village, Corn Law Rhymes and other poems (1833) — complete text on Ian S. Petticrew's radical and artisan poets site

- Novels by R. S. Surtees and Benjamin Disraeli in favor of the Corn Laws

Bibliography

Bentley, Nicolas. The Victorian Scene: A Picture Book of the Period, 1837-1901. London: Spring Books, 1971.

Content last modified April 1997

Images added 10 May 2014, 24 February 2019, & 18 June 2021; resources 16 January 2006