Wallington. [Click on this and the following images for more information.]

Wallington, the Northumbrian family seat of the Trevelyans, contains a magnificent cache of Pre-Raphaelite murals, paintings and sculptures. In Lady Trevelyan and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, John Batchelor reveals the full story and the attractive personality behind this far-flung outpost of High Victorian culture.

At first glance, the marriage between the art-loving Pauline Jermyn and the much older teetotal, vegetarian Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan might seem like a Dorothea/Casaubon arrangement, especially as Walter sent his future wife a box of fossils shortly before proposing to her. Pauline's diary entry for her wedding day in May 1835 is hardly more promising. All she writes is: "Married by Mr Casborne at half past eight" (15). But they both loved art as well as geology (hence those fossils), and the marriage turned out well, the very fact that it was childless allowing Pauline to direct her considerable energies to other forms of creativity.

When Pauline first visited her new husband's family at their Wallington estate, she was amusingly scathing about the figures and attire of his sisters, perhaps because they looked down on this diminutive sister-in-law who had brought nothing to her marriage but her sharp wits and an artistic sensibility. She described one of the sisters, for example, as having "a creepy curious body" and looking like a "fattish vampire" (23). On the other hand, Pauline was completely bowled over by Richard Grainger and John Dobson's redevelopment of nearby Newcastle, particularly admiring Grey Street, which she saw just days before Lord Grey's statue was to be placed on its column. If the town centre is impressive now, the pristine stone buildings must have looked quite spectacular in 1838.

Evidently excited by new ideas in architecture, Pauline at once realised that Wallington would benefit from an entrance hall. By the time her husband succeeded to his baronetcy, and she was actually able to rebuild and redecorate the house, she was in a position to achieve results as spectacular as those achieved in Newcastle itself. Trips to Europe, a close friendship with Ruskin, and her early involvement in the Oxford Museum project, had introduced her to the finest ideas and art of her age, and she had imbibed them eagerly and in her own way. And her contact with the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the cream of local talent gave her the very men best suited to execute her plans.

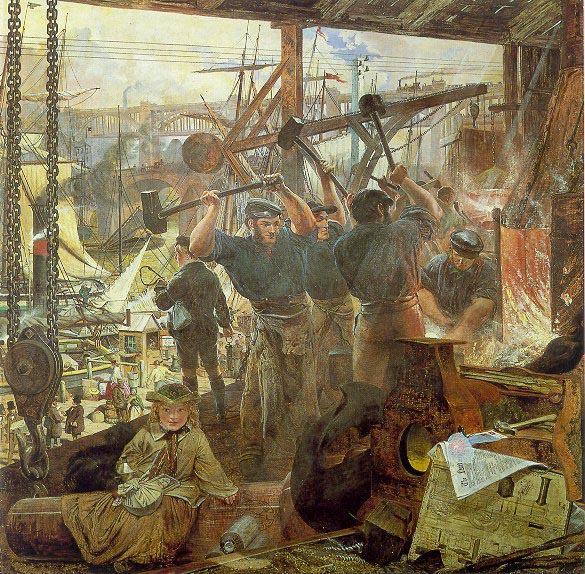

Above all, the inner courtyard of Wallington was to be converted into a central hall for display and entertainment purposes. This grand space was designed in 1852 by Dobson himself, just a few years after his completion of Newcastle's imposing railway station. The next step was to adorn it with murals, a cycle of huge paintings depicting the long and rich history of the area, and noble statuary. The chief artist was the Scottish but Newcastle-based Pre-Raphaelite William Bell Scott (although Ruskin, to Bell Scott's disgust, painted part of one pilaster with simple countryside plants, and other pilasters were decorated by Pauline herself, and visitors such as Arthur Hughes). The first in Bell Scott's great historical cycle was, inevitably, The Romans cause a wall to be built, in which one of the Roman officers has the features of John Collingwood Bruce, the antiquarian responsible for spreading the fame of Hadrian's Wall; and the last was, equally inevitably, the powerful Iron and Coal, a painting about industrial Tyneside to rival Ford Madox Brown's earlier, more famous Work. For the sculpture, Pauline commissioned one of the original members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Thomas Woolner. Woolner's major work Civilization, dominated by the touching mother-and-child piece known as The Lord's Prayer or The Trevelyan Group, was finally installed at Wallington in 1866, only months after Pauline's death from ovarian cancer. There are also works at Wallington by Burne-Jones, William Frith, Alexander Munro (who often visited Pauline at Wallington) and others.

Left to right: (a)Interior of the central hall, Wallington, with paintings and decoration by William Bell Scott, Alexander Munro, John Ruskin, and Pauline Trevelyan. (b) Iron and Coal by William Bell Scott. (c) The Romans cause a wall to be built, also by William Bell Scott.

The effect was so impressive as to be inspirational. In his chapter on "The Wallington Decorative Scheme," Batchelor explains:

In 1855, the year in which Pauline had conceived the Wallington scheme, a local journalist wrote in despair that the 'fine arts in Newcastle appear literally to be dead and buried', and that with the growing prosperity of the people of Newcastle and Sunderland came a growing ignorance of art and a preference for 'champagne and claret'. By 1962, that opinion had significantly changed. The Wallington scheme was recognised as an innovation of national as well as regional significance, and it was widely reviewed in the national press. The paintings were exhibited in London before finally being hung in Wallington. The only comparable (though not closely comparable) recent decorative scheme were the frescoes of Arthurian subjects painted by Rossetti, Burne-Jones, Morris, Prinsep and others in Dean and Woodward's new Gothic Union building at Oxford in 1857. Bell Scott's Wallington paintings prompted similar decorative schemes elsewhere in the country, such as the cycle of twelve historical paintings for Manchester town hall (depicting episodes in the history of Manchester from Roman times to the recent past) undertaken by Ford Madox Brown in the 1870s, and the later decorative scheme commissioned for the Scottish Portrait Gallery. [201]

Pauline's influence would therefore be felt far beyond the confines of Wallington itself.

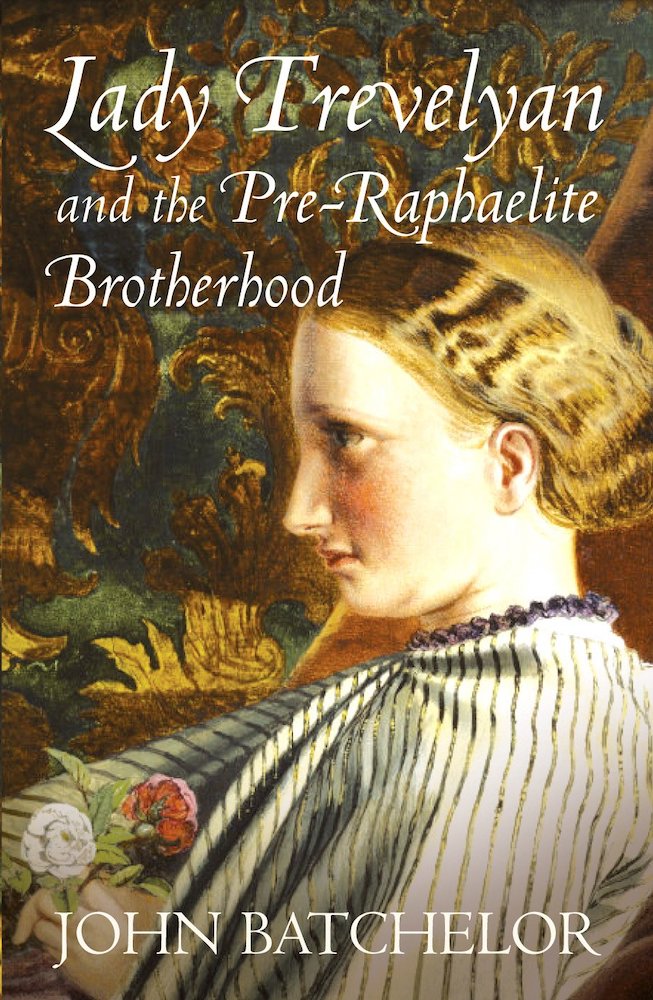

Appropriately, then, near the end of this chapter Batchelor turns from the major artwork to give some of his most heartfelt praise to Bell Scott's portrait of his patron herself, which is shown on the front cover of the book. This has, in fact, been much admired, an earlier critic writing, for instance, that the "vivacity and delicious sense of humour for which Pauline was renowned is much in evidence in this light, silvery portrait" (Rose 127). Rather unusually, the artist has depicted her in profile, to the left, rather than looking out at the viewer. Her hair is neatly drawn back, and she wears a white striped cape, trimmed at the neck. Held gently in her hands are two camellias, one white and one red. Behind her is a richly patterned hanging, with gold-brown leaves on a green background.

These decorative motifs are apt enough because both Pauline and her husband were keen botanists, but, more specifically, because camellias were considered to symbolise affection and admiration: red ones were thought to stand for "unpretending excellence," and white ones for "perfected loveliness"(see Connolly 85). No wonder, then, that Batchelor finds "the whole canvas irradiated with the artist's love for the subject" (141), and adds, "[t]here can be no doubt that Bell Scott was more than a little in love with Pauline" (142). It is worth repeating, however, that this did not intrude on her marriage: prominently shown in Scott's earlier portrait of Sir Walter (Sir Walter Calverley Trevelyan in the Saloon, 1853), is an ornamental pot of splendid white arum lilies. With their aura of beauty and innocence, they seem to suggest Pauline's presence there, close to her husband's side, as she so often was.

Indeed, despite being dogged by pain from her long undiagnosed illness, Pauline had by now mellowed into a wonderfully companionable wife, and a sympathetic and tactful friend. She managed Bell Scott himself ("her grumpy old Scotus," 226) with exquisite tact, and was almost motherly in the later phase of her close relationship with Ruskin, whom she had once termed "Master," and who would attend her deathbed with her husband. Towards the ultra-bohemian Swinburne, who spent much time on his grandfather's estate (Capheaton) nearby, especially when he was at Eton, Pauline was, in fact, distinctly motherly. Batchelor himself seems to have fallen under her spell, feeling perhaps much as her husband did when she finally died, with Sir Walter and Ruskin beside her, in 1866: "oh here were a mind & character combined, such as are rare" (230).

Yet John Batchelor's title is well-chosen. Though more excerpts from the forty-four volumes of Pauline's diary would have been welcome, it is not fair to judge the book as a straight biography. Had Batchelor decided to write one, the chapter on Swinburne alone suggests that he would have made a splendid job of it. But he has chosen instead to focus rather less on Lady Trevelyan in her own right, and rather more on her as a friend and patron of a remarkable group of artists — and, of course, on the legacy of these friendships at her beloved Wallington. Surely, this is exactly what this gifted but above all enabling woman would have wanted.

Bibliography

Batchelor, John. Lady Trevelyan and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. London: Chatto & Windus, 2006. 272 + xiii pp. £25.00.

Connolly, Shane. The Language of Flowers. London: Conran Octopus, 2004.

Rose, Andrea. Pre-Raphaelite Portraits. Yeovil: Oxford Illustrated Press, 1981.

Created 4 November 2006

Last modified 8 March 2024