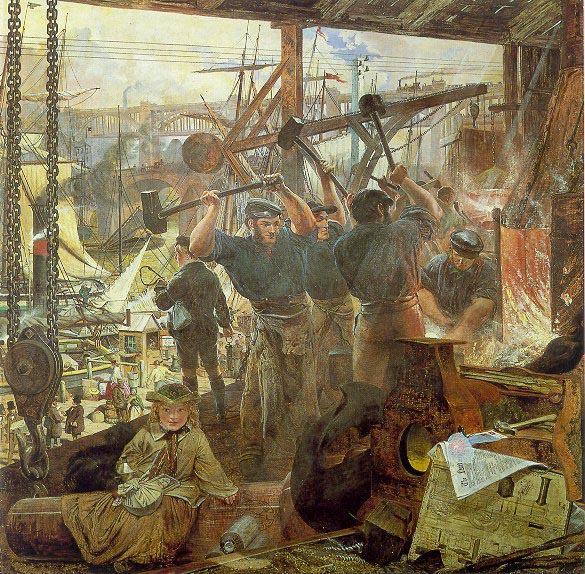

In the nineteenth century the Northumbrians show the world what can be done with iron and coal by William Bell Scott. 1861. Wallington, Northumbria. Courtesy Wallington, the National Trust.

According to John Batchelor, Scott painted Iron and Coal, the last and most important of the series at Wallington, between January and June 1861.

Bell Scott visited Stephenson's railway-engine works to see a locomotive wheel being forged to give him his central action, but the painting as a whole is a composite showing the Tyneside industries: an Armstrong gun barrel and a shell, a locomotive wheel, barges carrying coal, a train crossing Robert Stephenson's newly completed High Level bridge. One of the men wielding the hammers (the figure on the left) is drawn from Charles Edward Trevelyan, who in due course inherited Wallington.

Iron and Coal is a resonant title, which explicitly links the painting to the English School of geology: William Buckland had written that iron and coal were part of the dispensation of Divine providence. They 'increase the riches, and multiply the comforts, and ameliorate the condition of mankind' and were placed conveniently for these purposes as 'part of the design, with which they were, ages ago, disposed in a manner so admirably adapted to the benefit of the human race'. [Batchelor 140-141]

There were problems, however. Walter Trevelyan disliked the display of armaments in the picture, and Bell Scott himself seemed to feel that in the end he had packed too much into it: "The canvas is as full as it can hold. Every thing of the common labour life and applied science of the day, is introduced somehow, besides a mottled sunbeam done so realistically that the flies are beginning to buzz in my studio. . . . One must have one's joke even if one has to pay for it" (qtd. in Batchelor 144). — Jacqueline Banerjee

Bibliography

Batchelor, John. Lady Trevelyan and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. London: Chatto & Windus, 2006. [review by JB]

Last modified 29 October 2006