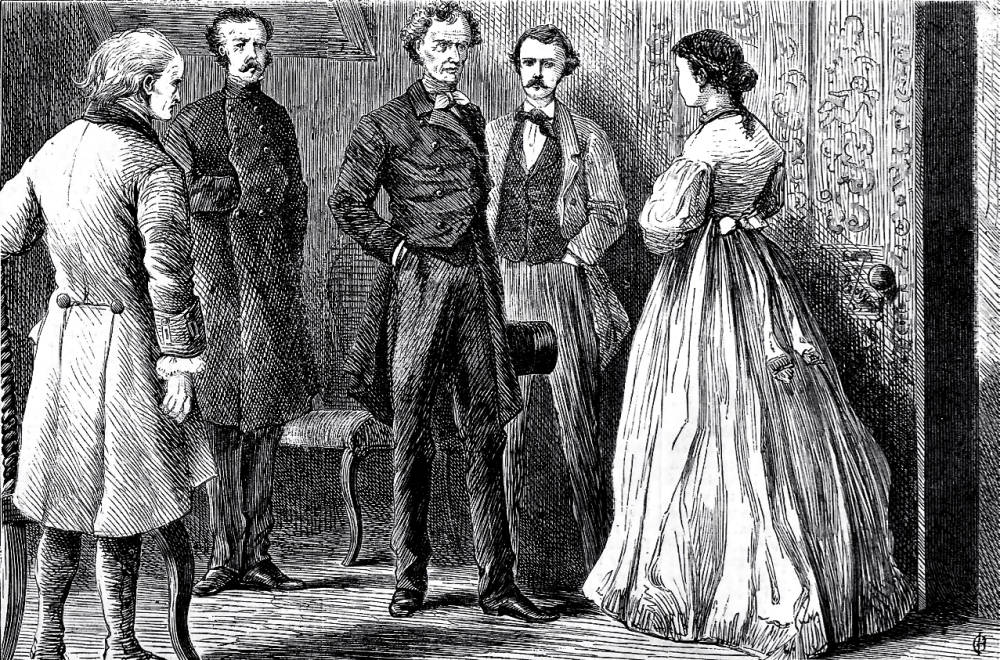

Sergeant Cuff, Lady Julia, and Gabriel Betteredge — uncaptioned vignette for the "The Story. First Period." — thirteenth illustration in the Doubleday (New York) 1946 edition of The Moonstone, p. 101. 7.1 x 10.8 cm. [Sergeant Cuff senses that the Diamond has not necessarily been stolen, and that the key to solving the mysterious is likely associated with a dress or nightgrown that has paint from Rachel's sitting-room door on it, necessitating checking the clothing of all members of the household.] Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Passage Illustrated

"I have already formed an opinion on this case," says Sergeant Cuff, "which I beg your ladyship's permission to keep to myself for the present. My business now is to mention what I have discovered upstairs in Miss Verinder's sitting-room, and what I have decided (with your ladyship’s leave) on doing next."

"I have already formed an opinion on this case," says Sergeant Cuff, "which I beg your ladyship's permission to keep to myself for the present. My business now is to mention what I have discovered upstairs in Miss Verinder's sitting-room, and what I have decided (with your ladyship’s leave) on doing next."

He then went into the matter of the smear on the paint, and stated the conclusions he drew from it — just as he had stated them (only with greater respect of language) to Superintendent Seegrave. "One thing," he said, in conclusion, "is certain. The Diamond is missing out of the drawer in the cabinet. Another thing is next to certain. The marks from the smear on the door must be on some article of dress belonging to somebody in this house. We must discover that article of dress before we go a step further."

"And that discovery," remarked my mistress, "implies, I presume, the discovery of the thief?"

"I beg your ladyship's pardon — I don't say the Diamond is stolen. I only say, at present, that the Diamond is missing. The discovery of the stained dress may lead the way to finding it."

Her ladyship looked at me. "Do you understand this?" she said.

"Sergeant Cuff understands it, my lady," I answered.

"How do you propose to discover the stained dress?" inquired my mistress, addressing herself once more to the Sergeant. "My good servants, who have been with me for years, have, I am ashamed to say, had their boxes and rooms searched already by the other officer. I can't and won’t permit them to be insulted in that way a second time!"

"(There was a mistress to serve! There was a woman in ten thousand, if you like!)

"That is the very point I was about to put to your ladyship," said the Sergeant. "The other officer has done a world of harm to this inquiry, by letting the servants see that he suspected them. If I give them cause to think themselves suspected a second time, there’s no knowing what obstacles they may not throw in my way — the women especially. At the same time, their boxes must be searched again — for this plain reason, that the first investigation only looked for the Diamond, and that the second investigation must look for the stained dress. I quite agree with you, my lady, that the servants' feelings ought to be consulted. But I am equally clear that the servants' wardrobes ought to be searched."

This looked very like a dead-lock. My lady said so, in choicer language than mine. — "The Story. First Period. Loss of the Diamond (1848). The events related by Gabriel Betteredge, house-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," Chapter 13, p. 101-102.

Commentary

Thus begins one of the great "closed room" mysteries of English literature, although in this case the whole country-house has been sealed on the night of the supposed robbery, with no one permitted to leave or enter the house from midnight until sunrise. If, of course, one the servants is not the culprit (the logical suspect here being the ex-convict Rosanna Spearman), then (unthinkably!) one of the house-guests or family must be responsible for the theft-that-may-not-be-a-theft.

Sharp sets up the scene as a dialogue between Cuff and Betteredge with Lady Julia in the middle, seated in the library (as signified by the books beside her). Cuff is deferential as he proposes a strategy to find the paint-smeared dress, and Betteredge is non-comital, although it may not yet have dawned on him that Cuff's scheme involves searching the wardrobes and luggage of guests and family as well.

Relevant Plates from the 1868 and 1890 Editions.

Above: The original serial wood-engraving in Harper's of Cuff's studying Rachel Verinder, "Sergeant Cuff's immovable eyes never stirred from off her face." (15 February 1868). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

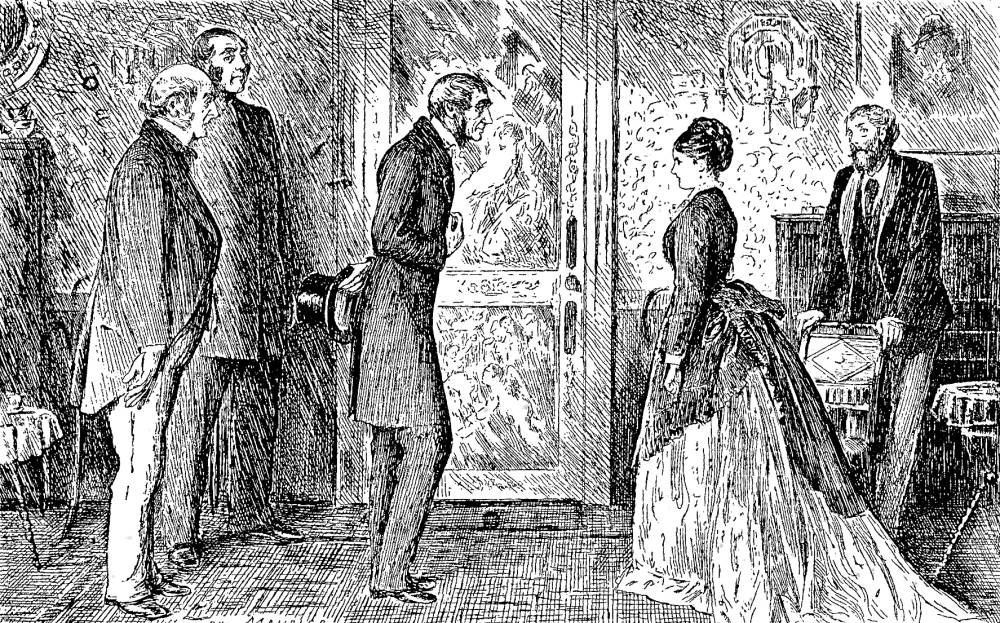

Above: George Du Maurier's "high society" drawing of the Sergeant, Betteredge, Lady Julia, and the assertive Rachel Verinder, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" (1890). [Click on the images to enlarge it.]

Related Materials

- The Moonstone and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in The Moonstone

- Introduction to the Sixty-six Harper's Weekly Illustrations for The Moonstone (1868)

- The Harper's Weekly Illustrations for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone (1868)

- George Du Maurier, "Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — p. 94.

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1890)

- Illustrations by John Sloan for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance (1908)

- 1910 illustrations by Alfred Pearse for The Moonstone.

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. with sixty-six illustrations. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. Vol. 12 (1868), 4 January through 8 August, pp. 5-503.

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With many illustrations. First edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, [July] 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Novel. With 19 illustrations. Second edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1874.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George Du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone. With 19 illustrations. The Works of Wilkie Collins. New York: Peter Fenelon Collier, 1900. Volumes 6 and 7.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With four illustrations by John Sloan. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1908.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

_________. The Moonstone. Illustrated by William Sharp. New York: Doubleday, 1946.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. With nine illustrations by Edwin La Dell. London: Folio Society, 1951.

Karl, Frederick R. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Scarborough, Ontario: Signet, 1984. Pp. 1-21.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Nayder, Lillian. Unequal Partners: Charles Dickens, Wilkie Collins, & Victorian Authorship. London and Ithaca, NY: Cornll U. P., 2001.

Peters, Catherine. The King of the Inventors: A Life of Wilkie Collins. London: Minerva, 1991.

Reed, John R. "English Imperialism and the Unacknowledged crime of The Moonstone. Clio 2, 3 (June, 1973): 281-290.

Stewart, J. I. M. "Introduction." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 7-24.

Stewart, J. I. M. "A Note on Sources." Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone. Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1966, rpt. 1973. Pp. 527-8.

Vann, J. Don. "The Moonstone in All the Year Round, 4 January-8 1868." Victorian Novels in Serial. New York: Modern Language Association, 1985. Pp. 48-50.

Winter, William. "Wilkie Collins." Old Friends: Being Literary Recollections of Other Days. New York: Moffat, Yard, & Co., 1909. Pp. 203-219.

Last updated 11 October 2016