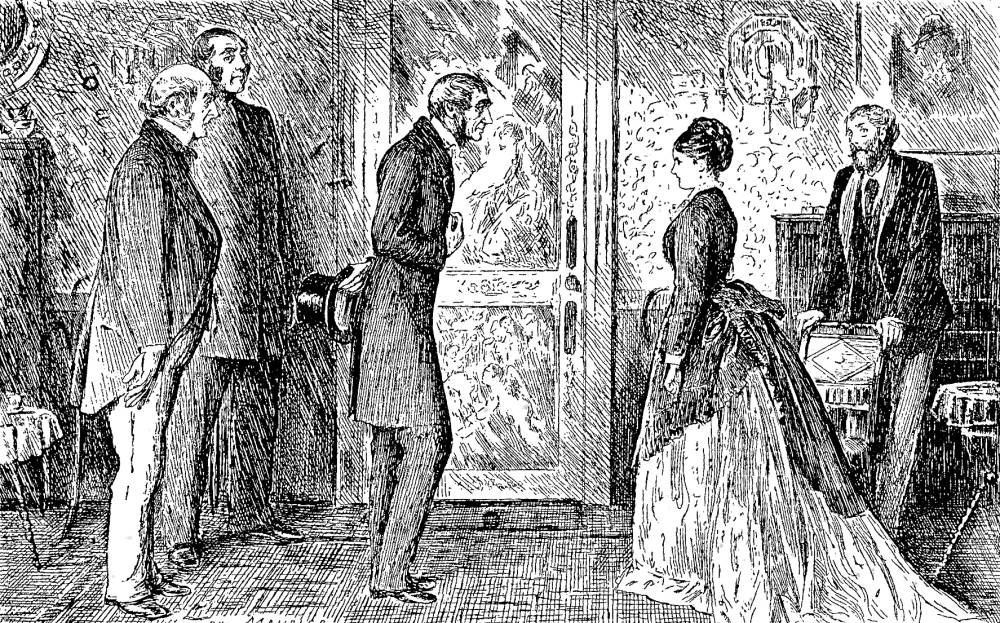

"Do you think a young lady's advice worth having?" — George du Maurier's frontispiece for Wilkie Collins's The Moonstone: A Romance. George du Maurier (1834-1896). The 1890 Chatto and Windus edition, illustrating page 94. Wood engraving, 9.5 cm x 15.1 cm, framed. The figures assembled in Rachel Verinder's sitting-room include (left to right) Gabriel Betteredge, Superintendent Seegrave, Sergeant Cuff, Rachel Verinder, and Franklin Blake. Behind Cuff is the paint-smeared door, about which Cuff is most interested as he believes that it is the key to discovering the thief. Rachel, for her part, proves strangely uncooperative.

Passage Illustrated

As the words passed his lips, the bedroom door opened, and Miss Rachel came out among us suddenly.

She addressed herself to the Sergeant, without appearing to notice (or to heed) that he was a perfect stranger to her.

"Did you say," she asked, pointing to Mr. Franklin, "that HE had put the clue into your hands?"

("This is Miss Verinder," I whispered, behind the Sergeant.)

"That gentleman, miss," says the Sergeant — with his steely-grey eyes carefully studying my young lady's face — "has possibly put the clue into our hands."

— 93 in "First Period. The loss of the Diamond (1848). The Events related by Gabriel Betteredge, House-steward in the service of Julia, Lady Verinder," Chapter 12.Commentary: Rachel's Assertiveness and Eccentricity

To the present-day reader Sergeant Cuff's initial interviewwith Rachel Verinder is hardly an emotional high point, and certainly not a particularly apt subject for a frontispiece, which should serve as a sort of visual overture and point towards the essential conflict of the novel. The initial appearance of the Indians or Herncastle's murdering the third Brahmin, a custodian of the Moonstone, would seem to be more suitable subjects for a keynote illustration. As the illustrator of The Notting Hill Mystery in Once A Week (1862-63), of Thomas Hardy's The Hand of Ethelberta (1875-76) and A Laodicean (1880-81), and (soon afterwards)the author of Trilby (1894), du Maurier was deeply involved in the production of both Sensation Fiction and what has been termed New Woman Fiction. The moment that he has seized upon underscores Rachel's strength of character and her ability to stand up to a room full of men who are bent on hearing her account of the smeared paint, the cause of which of course she cannot truthfully revealwithout implicating Franklin Blake as the thief.In other words, although Rachel is a phlegmatic figure apparently, in fact she is in the throes of an emotional conflict, having to choose between a highly valuable diamond and the man whom she loves — certainly a suitable for the frontispiece of a New Woman novel, the genre into which readers of 1890 might well have placed The Moonstone: A Romance, illustrated by George du Maurier and F. A. Fraser (London: Chatto and Windus).

Faced with the stress of having to confront two senior police officers in the presence of the man whom she loves and is trying to protect, Rachel Verinder is transformed from a wilful and relatively carefree eighteen-year-old aristocrat into a protofeminist heroine. After the theft of the Moonstone she becomes a subtle, powerful, and compelling character who is feminine in her feelings but masculine in her tenacity. Complex and unpredictable, she acts here according to the promptings of her heart (still loving the man whom she believes is a thief and a hypocrite) as well as of her mind (trying to outwit Cuff, having concluded that she saw Franklin steal the diamond). Through her dilemma, Collins demonstrates that the scientific, rational mind, which relies solely on physical evidence, can lead the thinker to false (albeit logical) conclusions: the way to the truth requires reconciling one's intuitions and one's thoughts. Eventually Rachel, who will emerge from her nightmare of doubt in both herself and Franklin, becomes an even stronger character. Like so many of Collins's heroines and the female characters whose stories du Maurier illustrated, Rachel transcends the limitations that Victorian society imposed upon women, and she becomes a fully-realised and interestingly motivated character. Her love for Franklin Blake stands in opposition to the selfishness her uncle, John Herncastle, the greed of her cousin Godfrey Ablewhite, and her cousin Drusilla Clack's attempts to impose her morality upon others. As Collins himself said in his preface, the "object" of The Moonstone "is to trace the influence of character on circumstances. The conduct pursued, under a sudden emergency, by a young girl [i. e., Rachel Verinder], supplies the foundation on which I have built this book." In other words, in constructing the 1890 frontispiece, George du Maurier responded directly to Collins's own cue.

Although hers is "only a young lady's opinion" and her auditors (entirely male) include two highly experienced detectives, she correctly asserts that (male) logic alone will be insufficient to detect the criminal and solve the crime. Cuff first incorrectly believes Rosanna Spearman stole the gem, and later incorrect believes the same about Franklin Blake, but in the end he rightly discovers that Godfrey Ablewhite is the actual thief. And everybody is wrong about the disguised Brahamins, who are in fact the rightful owners of the purloined gem. At first, having witnessed Franklin take her diamond and knowing of his past debts, Rachel cannot misunderstanding what she has seen. In a novel that often emphasizes the foreign, the mysterious, and the exotic, du Maurier in his frontispiece focusses instead upon the emotional and mental struggles of a New Woman. The scene he has chosen demonstrates her strength of character and determination — ironically, to thwart the investigation rather than advance it, despite the fact that she is the one who has been robbed.

Related Materials

- "The Moonstone" and British India (1857, 1868, and 1876)

- Detection and Disruption inside and outside the 'quiet English home' in "The Moonstone"

- Illustrations by F. A. Fraser for Wilkie Collins's "The Moonstone: A Romance" (1890)

- The "Harper's Weekly" Illustrations for Wilkie Collins's "The Moonstone" (1868)

- Frontispiece: "He felt himself suddenly seized round the neck."

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

Collins, Wilkie. The Moonstone: A Romance. All the Year Round. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Harper's Weekly: A Journal of Civilization. With 63 illustrations. 1 January-8 August 1868.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by George du Maurier and F. A. Fraser. London: Chatto and Windus, 1890.

_________. The Moonstone: A Romance. Illustrated by A. S. Pearse. London & Glasgow: Collins, 1910, rpt. 1930.

Leighton, Mary Elizabeth, and Lisa Surridge. "The Transatlantic Moonstone: A Study of the Illustrated Serial in Harper's Weekly." Victorian Periodicals Review Volume 42, Number 3 (Fall 2009): pp. 207-243. Accessed 1 July 2016. http://englishnovel2.qwriting.qc.cuny.edu/files/2014/01/42.3.leighton-moonstone-serializatation.pdf

Created 17 August 2016

Last modified 7 May 2020