- 1. Frontispiece (Part 11-12, 1858 June)

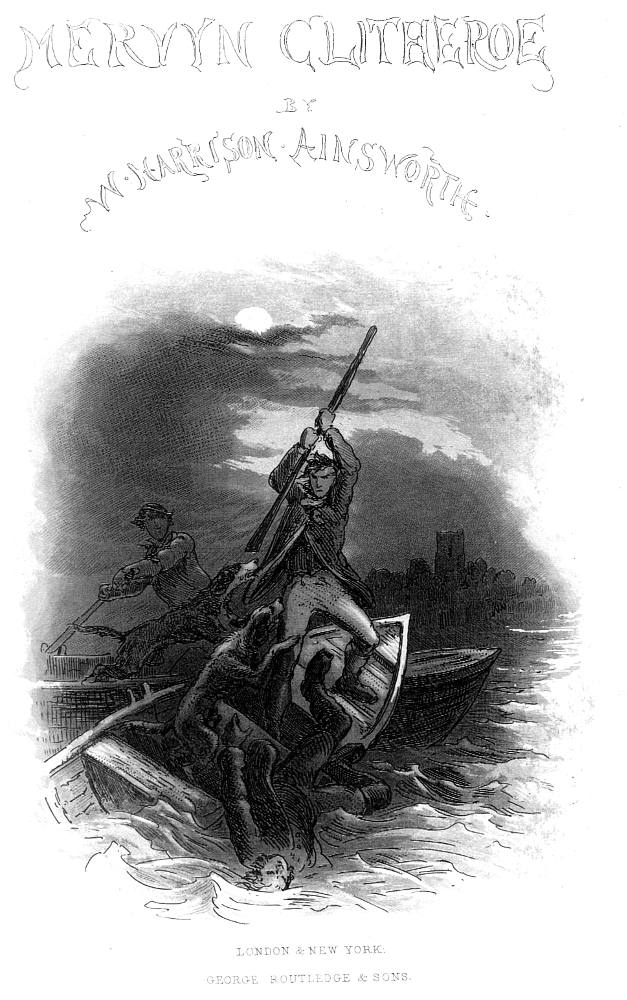

- 2. Vignette Title (Part 11-12, 1858 June)

- 3. A Bunker’s Hill Hero (Part 1 (1851 Dec.)

- 4. Who shot the Cat? (Part 1 (1851 Dec.)

- 5. My Adventure with the Gipsies (Part 2, 1852 Jan.)

- 6. Twelfth Night Merry-making in Farmer Shakeshaft’s Barn (Part 2, 1852 Jan.)

- 7. The Benevolent Physician (Part 3, 1852 Feb.)

- 8. The Dinner-party at the Anchorite’s (Part 3, 1852 Feb.)

- 9. A Nocturnal Alarm (Part 4, 1852 March)

- 10. My Uncle Mobberley’s Will is Read (Part 4, 1852 March)

- 11. My Altercation with Malpas Sale (Part 5, 1857 Dec.)

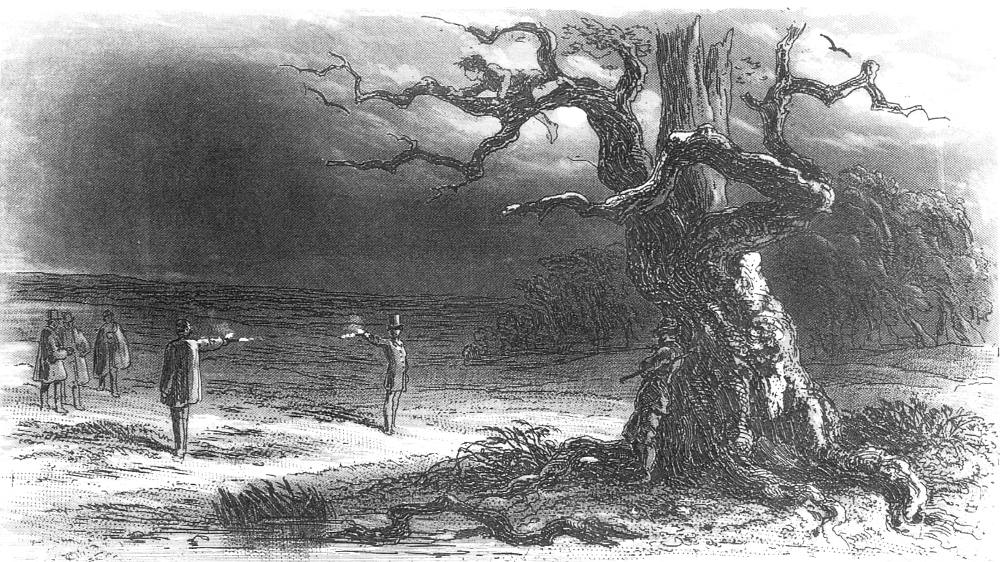

- 12. The Duel on Crabtree Green (Part 5, 1857 Dec.)

- 13. I receive Sad Intelligence from Ned Culcheth (Part 6, 1858 Jan.)

- 14. The Mysterious Bell-ringing at Owlarton Grange (Part 6, 1858 Jan.)

- 15. The Legend of Owlarton Grange (Part 7, 1858 Feb.)

- 16. My Adventure in the Haunted Chamber (Part 7, 1858 Feb.)

- 17. The Stranger at the Grave (Part 8, 1858 March)

- 18. The Conjurors Interrupted (Part 8, 1858 March)

- 19. I find Pownall in Conference with the Gipsies (Part 9, 1858 April)

- 20. The Rustic Fete at the Mill (Part 9, 1858 April)

- 21. The Deed of Settlement (Part 10, 1858 May)

- 22. The Meeting in Delamere Forest (Part 10, 1858 May)

- 23. The Examination before the Magistrates (Part 11-12, 1858 June)

- 24. Death of Malpas Sale (Part 11-12, 1858 June)

- Dark Plates for Mervyn Clitheroe.

- Advertiser for Mervyn Clitheroe in Davenport Dunn (1 December 1857).

Commentary

If one looks at the range of Harrison Ainsworth's novels, one might simply classify the pseudo-autobiographical The Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe as another "Lancashire Novel," a follow-up to the first historical novel in that series, The Lancashire Witches. However, Ainsworth in using the form of the Bildungsroman, a boyhood reminiscence, as well as a markedkly nineteenth-century setting, seems to have takenas his model Charles Dickens's David Copperfield, which Chapman and Hall had serialised between May 1849 and November 1850. The same publishers, attracted perhaps to Ainsworth's consciously emulating the recent;y published Dickens novel, began serialisation of Mervyn Clitheroe in December 1851. As Stephen Carver observes, "The central character is very recognisably the author himself." The physical setting of the opening of the story, early nineteenth-century "Cottonborough" (modelled on the manufacturing, north of England city of Manchester), and the book's dedication to "My contemporaries at the Manchester School" both suggest that Ainsworth has developed a protagonist who is very much like himself as a grammar school student. Although the reading public and the critics at first seem to have accepted this new direction from Ainsworth, formerly an historical novelist, sales fell so dramatically that Chapman and Hall terminated the project in March 1852. Perhaps even his most faithful readers yearned for a more conventional Ainsworth period romance, with criminal exploits, dashing escapes, and costume melodrama. In fact, Ainsworth dropped the whole project until his friend, Crossley, suggested he revive it with some of the usual ingredients in 1858.

At the conclusion of the fourth monthly instalment, issued in March 1852, appeared the following notice to alert serial readers to what the publishers seem to be envisaging will be a temporary interruption:

The first part of the ADVENTURES OF MERVYN CLITHEROE — 'part of a whole, yet in itself complete' — is now concluded. Some delay will probably occur in the continuation of the Story. The Author regrets it, but the delay is unavoidable on his part. Unforeseen circumstances are likely to compel him to suspend, for a while, his pleasant task; — pleasant, because many of the incidents and characters have been supplied to him by his own personal recollections, while the scenes in which the events are placed have been familiar to him since childhood. Ere long he hopes to meet his friends again; bidding them, meanwhile, a kindly farewell!" [cited by Vann, 27-28]

Chapman and Hall in fact abandoned the project because, as John Sutherland remarks, sales were not indicative of widespread interest in the serial. "In December 1857, Routledge undertook to complete the work, in twelve numbers, following up with a one volume edition" (431).

The story of Mervyn Clitheroe reads rather like a conventional Ainsworth plot with its lost inheritance and star-crossed lovers, but without the overall frame of great historical events and personages (which is why his die-hard fans felt so short-changed at the time) but, as they say, the devil is in the detail — the most interesting features by far are those which give us an insight into the way in which Ainsworth saw himself as a youth, his friends and the city of his birth. ["V. The Lancashire Novels. Ainsworth & Friends"]

In terms of the body of Phiz's work, these twenty-four engravings on steel preceded one of his most celebrated programs, the June through December 1859 monthly serialisation of Charles Dickens's A Tale of Two Cities. Whereas Phiz employed the dark plate strategy sparingly in the Dickens illustrations, a dozen of the sixteen engravings he produced for the Ainsworth novel in 1857-58 are dark plates, modelled on his work for Dickens's Bleak House (London: Bradbury & Evans, 1853). Beginning in 1847, Phiz began to experiment with creating dramatic effects through extreme chiaroscuro by etching ‘dark plates’, an effect he achieved by scoring the plate with closely set parallel lines. Such atmospheric illustrations as Phiz's interpretation the squalid Tom-all-alone's in Chapter 46 of Bleak House (April 1853) use intense shades of grey to describe twilight, evening, night, and gloomy interiors and invest them with suggestions of dark, melancholy moods ranging from the sinister, to the malignant, and the merely apprehensive.

When, after an hiatus of five years and seven months, Phiz returned to the project with new publishers, he had become enamored of the labour-intensive engraving style called "the dark plate." He had relied heavily on this atmospheric treatment of vistas, landscapes, and even urban slums in the illustrations for the second of the serialisation of Bleak House, numbers 11 through 20 (January through September 1853). Phiz decided to employe this engraving technique for a significant number of the illustrations in Books Two and Three (December 1857 through June 1858) of Mervyn Clitheroe, including the frontispiece and title-page vignette. Of the twenty-four steel-engravings for the Ainsworth novel, none of the eight illustrations in Book the First (December 1851 through March 1852) are dark plates; however, twelve of the sixteen plates for the second and third books demonstrate Phiz's mastery of this engraving technique.

Phiz experienced a lean year in terms of commissions in 1859 was a lean year, whereas he had been extremely busy in the previous year, during which he illustrated eight books besides The Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe:

- Aunt Mavor's Third Book of Nursery Rhymes*

- Christmas Cheer*

- Legendary Tales* by Margaret Gatty

- London at Dinner, or Where to Dine* by Robert Hardwick

- The Discontented Children and How They were Cured* by Mrs. Kirby

- Paved with Gold by Augustus Mayhew

- The Buccaneers* by Walter Thornbury

- Acting Proverbs; or, Drawing Room Theatricals by E. Townsend, ed.

* denotes wood- rather than steel-engravings.

However, the only other literary work or canonical writer that Phiz illustrated during that period of many commissions was the second-tier writers Augustus Mayhew, a minor dramatist and frequent contributor to the Illustrated London News, and journalist and occasional historical novelist Walter Thornbury, then thirty years old and at the earliest stages of his writing career. Although Mayhew's slight novel Paved with Gold offered Phiz opportunities for picturesque scenes, and Thornbury's historical study plenty of swashbuckling material, neither could be classified as serious literature. No wonder, then, that Phiz threw his creative energies into the steel-engravings for the Ainsworth novel. In the next year, in contrast, he illustrated three significant works by three popular authors: Dickens, Charles Lever, and Harriet Beecher Stowe. One may even regard Phiz's work as preparatory for his work on one of the periods greatest works of historical fiction, A Tale of Two Cities. In terms of style, a number of the plates, especially those for Book One, are reminiscent of Phiz's work for the childhood scenes in David Copperfield (May 1849 — November 1850).

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Bibliography

"Ainsworth and Friends." Chapter V: "The Lancashire Novels," in Essays on 19th Century Literature & The Gothic, posted 16 January 2013; last updated October 2018. Online version available from wordpress.com — Dr. Stephen Carver's Blog. Web. 8 October 2018.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe (1851-2; 1858). Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Routledge, 1882.

Carver, Stephen. The Life and Works of the Lancashire Novelist William Harrison Ainsworth, 1805–1882. Lewiston: Edwin Mellen Press, 2003.

Ellis, S. M. William Harrison Ainsworth and His Friends. Volume 2. London: Garland Publishing, 1979.

Lester, Valerie Browne. Phiz: The Man Who Drew Dickens. London: Chatto and Windus, 2004.

Steig, Michael. Dickens and Phiz. Bloomington: Indiana U. P., 1978.

Sutherland, John. "Mervyn Clitheroe." The Stanford Companion to Victorian Fiction. Stan

Vanden Bossche, Chris. Reform Acts: Chartism, Social Agency, and the Victorian Novel, 1832-1867. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press, 2014. [Review by Andrzej Diniejko].

Vann, J. Don. "William Harrison Ainsworth. Mervyn Clitheroe, twelve parts in eleven monthly installments, December 1851-March 1852, December 1857-June 1858." New York: MLA, 1985. 27-28.

Worth, George J. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Created 28 October 2018

Last modified 17 March 2021