Death of Malpas Sale by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), twenty-second serial illustration for William Harrison Ainsworth's Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe, Parts 11-12 (June 1858), Book the Third, Chapter XVIII, "The Steeple-Chase," facing p. 359. Steel etching, 9.5 cm high by 17.5 cm wide, vignetted. Source: Ainsworth's Works (1882), originally published in the final serial instalment by George Routledge and Sons, London. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Passage Illustrated: Poetic Justice and a Melodramatic Closure

Scarcely had we taken up a position, when a bell was rung, informing us that the riders had started, and we presently caught a glimpse of them speeding across the clear space on the near side of the mill. At this moment Captain Brereton took the lead, though Malpas was not far behind him. Both were in jockey-dresses, Malpas wearing a blue cap, with a white jacket crossed by a broad sky-blue stripe, and his opponent a white cap and a pink jacket. as far as could be judged, they seemed pretty well matched in regard to horses, and both rode remarkably well. . . .

. . . . In this position I think I must have caught the eye of Malpas Sale, though I cannot be sure, but it seemed to me that he noticed me, and slightly swerved. Be this as it may, a sudden flush overspread his countenance, which had hitherto been pale with excitement. However, he held on unfalteringly. He was now full twenty yards in advance of captain Brereton, and the crowd of spectators collected at this point cheered him as winner. With these shouts ringing in his ears he charged the brook.

From the style in which his horse jumped I thought the animal would have landed him in safety — but I was mistaken. A terrible crash told me that an accident had happened. But I scarcely saw it, for all passed like a vision before my swimming eyes. The horse was down, and Malpas was lying, stunned and bleeding, and with fast-approaching death written in unmistakable characters on his countenance, at the foot of one of the pollard-trees, against which he had been dashed. A moment before he had been in full of power, pride, triumph — now he lay there helpless as a crushed worm — dying!

In the midst of the fearful outcries occasioned by this disastrous occurrence, Captain Brereton, who could not, of course, check himself, leaped the brook, with better luck than Malpas, landing upon a firm spot on the bank, and, avoiding the pollards, went on, shouting that he would bring medical aid directly. But it would be of no use. All the surgeons in Cheshire, or in England, could not help Malpas now.

As soon as Captain Brereton was out of the way, we rushed to Malpas, but he besought us not to move him, for his agony was excruciating. At this moment, a piercing shriek arose, and Rue rushed forward. Her wrongs were forgotten, and all the tenderness she had once felt for her betrayer returned to her breast. Kneeling beside him, she took his head gently upon her lap, and strove by every means in her power to alleviate his sufferings. Aware who was near him, the dying man thanked her by his looks. [Chapter XVIII, "The Steeple-Chase," pp. 358-359.]

Commentary: Malpas and his Confederates Punished by Providence

Malpas does not live to be disgraced by a guilty verdict in a court of law as his impetuosity and ego lead him to attempt a perilous jump in a steeplechase. And, coincidentally, his life-long rival, Mervyn Clitheroe, on his way to see the constables arrest Malpas, arrives on the scene just in time to see poetic justice executed upon his amoral, arrogant antagonist. The figure of the jilted Gypsy girl, Rue, is immediately recognizable, and we may take her presence as Providence's punishing the rake for his callous rejection of the woman who unquestioningly (and illogically) continues to love him, although she knows him to be a thorough villain of the haughty, aristocratic variety.

As the last regular serial illustration, Death of Malpas Sale, marks the culmination of the rivalry between he protagonist and the antagonist, Phiz uses the scene to summarize his delineation of the story's principal characters, among whom, however, Apphia is notably absent as Ainsworth has not included her. On the other hand, Phiz has carefully worked in all the members of the male supporting cast — Phaleg, Obed, Pownall, Hazilrigge, Culchetch, Malpas's groom, Spring, and Major Atherton, all more or less as Ainsworth has described them, although for the sake of emphasis the illustrator has moved the groom's inspecting the horse's legs for damage away from the centre of the action, the expiring antagonist:

Malpas at last made me out, and fixing his glazing eyes upon me, faltered forth:

"Have you got it? — the will!"

"It is here!" I cried, exhibiting the document to his failing gaze.

His looks expressed satisfaction, and he said faintly,

"It is well. I shall die easier for your forgiveness, Mervyn." [360]

Significantly, then, Mervyn grasps a roll piece of paper, which the text identifies as the chief object of contention between the principals: the missing will of Uncle Mobberley. Meanwhile, Malpas's surly confederate, Phaleg the Gypsy, his son Obed, and the slippery confidence man, Simon Pownall, receive their just desserts, all in fulfilment of Victorian expectations for poetic justice:

What a contrast does his gay attire offer to his ghastly looks! He is supported by the poor gipsy girl whom he has wronged, who watches him with intense anxiety, and would lay down her life to save him. Behind, stands his groom, holding his unlucky steed, which is but slightly injured. Amongst he spectators of the accident are many who have known the dying man, and are affected in various ways. Cuthbert Spring and Old Hazy, who are standing near the sufferer, seem quite horrified by the dreadful occurrence, and so does Ned Culchetch, but Major Atherton looks grimly on. He has seen death too often on he battle-field to be moved. But here is another group on which the spectacle might be expected to produce a powerful effect — a group consisting of the reckless young man's evil associates, Simon Pownall and the gipsies. How are they affected? Phaleg and his son look on with sullen unconcern, and the vice-hardened countenance of the elder gipsy displays no emotion whatever. Obed is not quite so stoical, but even he has a callous look. But Pownall, who is seated on the ground, averts his gaze, and tries to stop his ears with manacled hands. [360]

Ainsworth's use of the historic present here, implying immediacy, may in fact be based on a summary of the scene for the illustrator as it lays out precisely who the figures are and how they are juxtaposed, so that, for example, Pownall, much dishevelled, holds his head in his hands as he sits on the ground, upper right. In particular, Phiz has added to the backdrop of pollarded willows elements of the racecourse that Ainsworth had sketched in prior to his description of the accident: the throng of spectators on foot and in carriages, the stands filled chiefly with ladies, and the large flags marking the course. Barely sketched in at the bottom of the frame is a significant detail: the brook which marks the boundary of the Nethercrofts estate, supposedly upwards of thirty feet wide at this point — presumably Phiz intends the reader to imagine this as extending outside the frame to his or her vantage point. At the vey close of the chapter, Mervyn's stalwart picaresque companion, Ned, notes the irony of the site of the accident:

"No sooner does he touch the land he has coveted, and has striven to wrest from the rightful owner, than his horse dashes him against a tree, and he dies at the foot of the man he has wronged. It looks like a judgment." [361]

All that remains is for Major Atherton to disclose to Mervyn over the grave of the mother's protagonist that he is in fact Mervyn's father. Phiz stage-manages the entire scene masterfully, but perhaps without the conviction with which he imbues the Nemesis that Dickens visits on the hypocrites of David Copperfield, Uriah Heep and the gentleman's-gentleman, Littimer, in the final, double number of November 1850. But perhaps his more exuberant, caricatural style of ten years earlier was much better suited to providing a comic turn on Poetic Justice.

Poetic Justice in Mervyn Clitheroe and David Copperfield

Cecily. Yes, but it usually chronicles the things that have never happened, and couldn’t possibly have happened. I believe that Memory is responsible for nearly all the three-volume novels that Mudie sends us.

Miss Prism. Do not speak slightingly of the three-volume novel, Cecily. I wrote one myself in earlier days.

Cecily. Did you really, Miss Prism? How wonderfully clever you are! I hope it did not end happily? I don’t like novels that end happily. They depress me so much.

Miss Prism. The good ended happily, and the bad unhappily. That is what Fiction means. — Miss Laetitia Prism on the conclusion of her lost novel, in The Importance of Being Earnest (1895), Act II, pp. 98-99.

Human justice is flawed, incomplete, and not always wholly appropriate. However, the Victorians subscribed to the notion of Divine Justice or Nemesis, which would always, as W. S. Gilbert wrote in the operetta The Mikado (1885), "let the punishment fit the crime" (II, 339). The readers and audiences of the era applied the principle equally to comedy and melodrama, the novel, and the narrative poem. Seventeenth-century critic Thomas Rhymer coined the term "Poetic Justice" in The Tragedies of the Last Age Consider'd (1678) to signify in literary texts (as opposed to real life) the closure's distribution of both rewards and punishments, the former to virtuous characters such as Dickens's David Copperfield and Ainsworth's Mervyn Clitheroe, and the latter, again in due proportion, to wrong-doers, whether those who are merely hypocritical and deceitful such as Uriah Heep and James Littimer in the Dickens novel, or those who have committed actual crimes, such as Simon Pownall and Malpas Sale. Such a system is hardly viable in tragedy, in which the suffering is greater than the protagonist merits, but is highly appropriate to melodrama, arguably the dominant genre in nineteenth-century drama. Littimer, Steerforth's highly discreet servant, abets his master's abduction of Emily Peggotty, and is subsequently imprisoned for petty theft. White-collar criminal Uriah Heep, on the other hand, has embezzled from his employer, Mr. Wickfield. Whereas the crimes of Pownall and Phaleg in Mervyn Clitheroe merely merit jail-time, Malpas Sale, who has seduced another's wife and material deceived his relatives, has violated his society's norms. Having persuaded a married woman to abandon her husband and having stolen a relative's inheritance, he has committed more serious crimes for which he might be prosecuted — suppression of a will and attempted murder. Steerforth, although a more complicated antagonist than Sale, has committed acts of hubris, or excessive pride, and therefore suffers the effects of divine rather than human retribution, perishing in an act of God, a shipwreck, just as Ainsworth's suave villain succumbs to injuries he has sustained in a steeplechase accident. Although both James Steerforth and Malpas Sale have transgressed social codes, the former has technically committed no crime, and the latter with the assistance of an able barrister may once again evade justice, just has he did earlier when Mervyn and Ned accused him of torturing and murdering Simon Pownall. Moreover, as Malpas proved to be Mervyn's Nemesis in the shooting of the cat, a sadistic act for which Malpas made Mervyn look responsible, so here Mervyn's appearance at a crucial moment in the execution of the jump led to the accident, suggesting that Mervyn operated as Malpas's Nemesis. The conclusion reinforces the power of Poetic Justice:

Mervyn Clitheroe (1858)

After many disappointments, Mervyn recovers the will from Pownall, with the assistance, witting or unwitting, of several quite diverse characters: Doctor Foam, the Cottonborough physician; Old Hazilrigge, the superstitious owner of Owlarton Grange; Ned Culcheth, the gamekeeper whose wife Pownall has kidnapped for Malpas; Rue, Phaleg's daughter, whom Malpas has seduced; Cuthbert Spring, a man-about-Cottoborough, in love with Hazilrigge's sister; and "Major Atherton," who turns out to be Mervyn's father. Malpas is killed in a steeplechase accident. The Brideoakes are revealed to be Jacobite nobility. Mrs. Brideoake's feelings toward Mervyn are softened by these developments and disclosures, and the novel ends with the lovers happily paired off: not only does Mervyn marry Apphia, but John Brideoake marries Hazilrigge's niece and Cuthbert Spring Hazilrigge's sister. [Worth, p. 50]

A More Subtle Nemesis: Uriah Heep and Littimer in Prison in David Copperfield

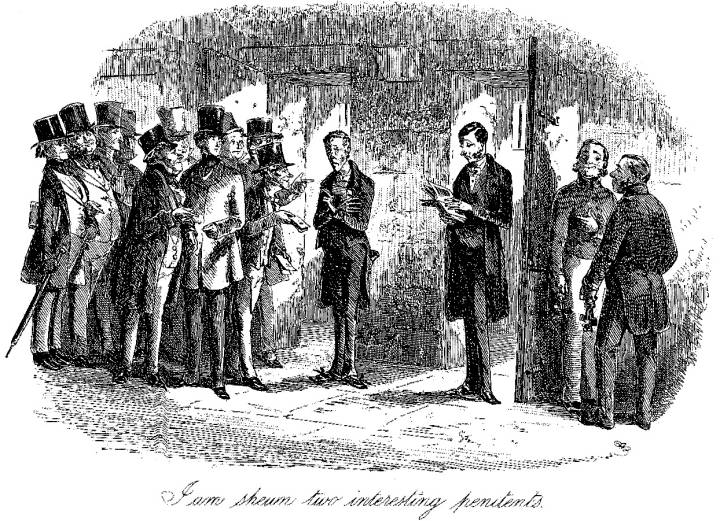

Above: Phiz's mastery of a more subtle and humorous Nemesis is evident in his November 1850 illustration for Dickens's David Copperfield: I am shewn two interesting pewnitents. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image, colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Bibliography

Abrams. M. H. "Poetic Justice." A Glossary of Literary Terms. 5th edition. Montreal and Toronto: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston, 1988. 144.

Ainsworth, William Harrison. The Life and Adventures of Mervyn Clitheroe (1851-2; 1858). Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'). London: Routledge, 1882.

Gilbert, William Schwenck. "A More Humane Mikado." The Mikado. The Complete Annotated Gilbert and Sullivan. Ed. Ian Bradley. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1996. Act Two. 621-625.

Vann, J. Don. "William Harrison Ainsworth. Mervyn Clitheroe, twelve parts in eleven monthly installments, December 1851-March 1852, December 1857-June 1858." New York: MLA, 1985. 27-28.

Wilde, Oscar. The Importance of Being Earnest. (1895). Ed. Samuel Lyndon Gladden. Peterborough, ON: Broadview, 2010.

Worth, George. William Harrison Ainsworth. New York: Twayne, 1972.

Last modified 9 January 2019