[In the following selections from Pattinson's late-nineteenth-century book on British passenger railways, he points out that the North-Eastern has many good points — high-powered modern locomotives, comfortable, safe coaches, and excellent stations in the major cities it serves — but it just can't get anywhere on time! I have adapted Pattinson's subheadings and added one (about the line's tardiness). — George P. Landow.]

Punctuality is not a strong point with the North-Eastern. There seems to be a sort of happy-go-lucky discipline in force on their local and branch lines.

General Description of the Line

This great system extends in all directions over the north-eastern district of England, and is about 1,550 miles in length. It is almost absolutely without competition, and is, consequently, able to pay high dividends. Over its main line, however, run the East-Coast expresses from London to Scotland, in fierce rivalry with the West-Coast route.

Starting from Shaftholme Junction, near Askern (north of Doncaster), the main route runs through York, Thirsk, Darlington, Durham, and Newcastle to Berwick. The company's expresses in connection with the Great Northern do not start from Askern, but are brought into York by the great Northern Company. From this point all the way to Edinburgh the North-Eastern takes charge of the running, the last 57 1/2 miles being over North British property. Many branches radiate from this trunk, and are of varying importance — from the little mineral line on which passenger trains are only run as a convenience, to the important section which requires its two or three expresses each way per day. Some of the latter we shall here describe. They are as follows: from Leeds via Milford Junction and Selby to Hull; from Hull by the somewhat circuitous Yorkshire coast-line through Driffield, Bridlington, Scarborough and Whitby to Saltburn; from York via Malton to Scarborough — a most important line in the season, with a branch to Whitby from Malton; from Leeds to York; the very important branch (almost a main line in itself from Leeds through Harrogate, Thirsk or Northallerton and Stockton to Hartlepool; from Newcastle through Sunderland and Wellfield Junction to Hartlepool in the east, and to Stockton and Middlesborough in the south; from Newcastle to Carlisle; from Newcastle to Tynemouth; and from Bilton Junction via Alnwick to Coldstream. Besides these, there are numerous others, not important as serving large populations, but interesting as opening out many beautiful localities. Such are those from Harrogate to Pateley Bridge; Northallerton to Hawes; Dalton Junction to Richmond; Darlington to Kirkby Stephen, dividing there into lines for Penrith to the north, and for Tebay to the west; Haltwhistle to Alston; and Berwick to Kelso. The scenery on these sections, together with the beautiful coast-line seen south of Berwick from the through expresses, entitles the North-Eastern to a high position as a picturesque route. To conclude, there are the little mineral lines all over Durham, and a number of agricultural branches in the east and north-east of Yorkshire, which look almost like main routes on Bradshaw's map, but are, in reality, as often single lines as not.

Travelling Facilities

The North-Eastern, although cumbered with numerous lines of merely local interest, possesses an excellent field in which to display its capabilities in the matter of train service. The company, however, do not take advantage of all the opportunities in their hands, and some of the important sections are rather hardly treated. The main-line service is good, if we consider it merely as a means of serving the towns on the North-Eastern system only; but looked at as an integral part of the East-Coast service from London to Edinburgh and Scotland, one must confess that the North-Eastern does less in the way of fast running than either the Great Northern, Midland, London and North-western, or Caledonian Companies, which are also engaged in the through Scotch traffic. . . Communications might be improved in many ways, especially from York to the important coast towns.

We have always considered that Leeds was badly treated by the North-Eastern. Owing to their lack of energy, the rival Midland route is able to secure a great part of the traffic from this important town to Scotland.

This railway's lateness

Punctuality is not a strong point with the North-Eastern. There seems to be a sort of happy-go-lucky discipline in force on their local and branch lines. Trains are regularly five to ten minutes late. This is certainly not much — but at the same time it shows that there is no right discipline in these matters, and without attention to these little details railway management is not a success. Then we find the same thing happening to the very important through expresses. They are handed to the North-Eastem at York, for conveyance northwards, with great punctuality. This is not retained long, and at Edinburgh their lateness is simply astonishing. The writer happened to be in that city during the summer of 1890, and was surprised to notice that the arrival of the south trains from 20 to 50 minutes late was of daily occurrence. The trains for London were in an even worse plight. That marvellous railway, the North British, which at that time, apparently, never felt at home unless its trains were an hour or so late, did not hand the trains to the North- Elastern with the slightest approach to punctuality. Once away from Edinburgh the North-Eastern frequently lost time in running, and on the arrival at York the trains were late beyond retrievement. This method of dallying with important expresses, so unlike what one sees on the high-pressure North-Western and Caledonian systems, has told greatly on the East-Coast traffic since that time. The crisis was reached in September, 1890, when no fewer than 68 per cent of the trains arriving at King's Cross from Scotland were over 30 minutes late. Many of them, doubtless, were over 130 minutes late.

The North-Eastern local services are generally more remarkable for frequency than for punctuality. Many of the branches are exceedingly well served with trains, and no one can accuse the company of treating their district badly because it is in their power to do so. At Newcastle there is a very large local service to be dealt with.

Rolling Stock and General Accommodation

The North-Eastern passenger rolling stock usually affords excellent accommodation. We shall make a few remarks on the deservedly- admired stock jointly owned by the three East-Coast companies later on. On the small branches certainly many of the old coaches are not so roomy as they might be, but, generally speaking, the stock is extremely comfortable. Few modern improvements have yet been introduced, however, and, at the time of writing, coaches fitted with lavatories are rarely seen, and it is only lately that the directors have come to the conclusion that gas is superior to oil as an illuminant. In another important point, however, the company fully satisfy requirements. There are few safer lines in the kingdom, every carriage has the VVestinghouse brake, and the permanent way is well maintained. The line is also carefully signalled, and a noteworthy feature is the liberal accommodation provided at the principal stations. York in particular is universally admired, and generally allowed to be the finest station in England. Durham, Darlington, Hull, Sunderland, Tynemouth, and Newcastle are also well up to modern requirements.

Locomotives

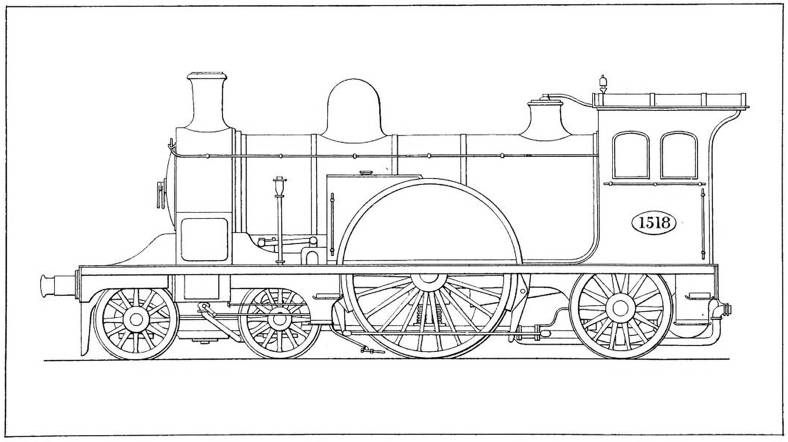

The North-Eastern Railway 1518, a 4-4-0 two-cylinder express engine. Designer: T. W. Worsdell. Source: Pattinson, British Railways (1893).

It will be noticed that the dimensions [of this railway's passenger locomotives] are well-nigh colossal, especially in the case of the 1520 class of singles, which are almost the heaviest passenger engines in the country, and much superior to any work they have to do on the North-Eastern.

But besides these heavy passenger types, Mr. Worsdell has built nearly 200 goods engines on the compound principle and many tank engines suitable for either short passenger journeys or for shunting purposes. Ail of them are unusually symmetrical in design, and are painted a bright green. The Westinghouse brake is used.

Related Material

Bibliography

Pattinson, J. Peabody. British Railways: Their Passenger Service, Rolling Stock, Locomotives, Gradients, and Express Speeds. London: Cassell, 1893. Internet Archive version of a copy in the Stanford University library. Web. 26 January 2013.

Last modified 26 September 2014