[The following passages are excerpted from Pattinson's late-nineteenth-century book on British passenger railways. — George P. Landow.]

Of the more recent Great Western locomotives it may be said that they are, in general design, of very striking appearance. There is at present no other company so lavish in the display of the brighter metals in the exterior fittings of boiler, framework, etc., to which we were accustomed on almost every line in bygone days, but which in these times does not seem to find favour on other railways.

General Description of the Line

This is much the longest of the English systems, and has a most formidable array of main lines and branches, extending in the aggregate to nearly 1,900 miles. The other large companies are, as a rule, content with one main line; the Great Western has no fewer than three, all converging to its terminus at Paddington (image). The oldest, though perhaps not the most important, of these except in so far that it gives the company its name is the route from London through Swindon, Bath, Bristol, and Taunton, to Exeter, on to Plymouth, and beyond that to Truro and Penzance. This is the longest stretch of main line in the kingdom, the distance from Paddington to Penzance being 326 ½ miles; whereas from London to Carlisle via Nottingham, Sheffield, and Leeds by the Midland route is only 316 ¾, and the length of the Highland main line from Perth to Wick only 305 ¼ miles. Besides this distinction, it has another, and that, too, a most interesting one. The whole of the above distance was, until May, 1892, laid with a gauge of 7 feet, although excepting on the extreme westerly portion an extra rail for narrow-gauge (4 ft. 8 ½ in.) traffic requirements was inserted between the broad-gauge metals. It would be beside our purpose to enter into the prolonged controversy which in the infancy of the railway system was carried on with such enthusiastic warmth by the respective partisans of the broad and narrow gauges. . . .

The principal branches diverging from this main route are : On the south, from Slough to Windsor; Reading to Basingstoke; Reading via Hungerford and Devizes to Bath; Chippenham via Westbury to Salisbury, and vid. Frome and Yeovil to Weymouth, from which port the company have of late years established an excellent service to the Channel Islands in competition with the South- Western; from Yatton to Wells; from Newton Abbott to Torquay and Dartmouth; and from Truro to Falmouth. On the north the chief offshoots are from Maidenhead to Oxford via Thame; Yatton to Clevedon; Puxton to Weston-super-Mare, a rising watering-place; Taunton to Minehead, for Lynton and the picturesque North Devonshire coast; and from Taunton to Barnstaple and Ilfracombe via Dulverton. Besides these, there are many other branches of secondary importance, which it is scarcely necessary to mention here.

The second main route of the Great Western is that deflecting from the line we have just described at Swmdon, and proceeding up the Stroud valley to Gloucester, thence trending south-west and west through Newport, Cardiff, Neath, Llanelly, and Carmarthen Junction to New Milford. Much of the traffic, however, between South Wales and London is conducted through the famous Severn Tunnel, and by this route trains continue along the first of our main routes, through Bath and Bristol (Stapleton Road), dive below the Severn, and emerge at Severn Tunnel Junction, nearly ten miles east of Newport. On this main line there are several branches, but scarcely any of the first importance, generally being of more account from a mineral than from a passenger-traffic point of view. Of greater consequence, however, are those from Newport to Pontypool Road, with the deflecting portions going north and east to Hereford, and by way of Malvern to Worcester, and going west through Merthyr and Neath to Swansea; and the line between Gloucester and Hereford David Ross.

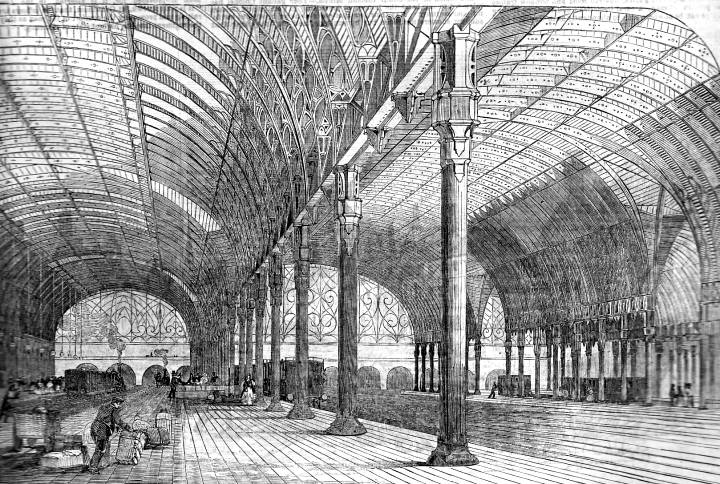

Left: Early London Railways. (The Great Western track appears at the left of the diagram.) Right: Paddington Station in 1874. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Our third main line is the most valuable of all. It leaves the Exeter route at Didcot, and runs north through Oxford, Leamington, and Warwick to Birmingham. From this important centre it continues northwards past the thickly-studded towns of the Black Country and Shrewsbury, runs through the far-famed vale of Llangollen, touches Chester, and finally reaches Birkenhead. Few main lines of similar length have so many populous or interesting places on their route. The branches are numerous, and generally leave the main line on the west From Oxford a line runs to Chipping Norton Junction, at which point one line goes west to Cheltenham, and another north to Worcester, and then along the Severn Valley line past Bridgnorth to Shrewsbury, there joining the direct route vid Birmingham. The other branches of importance are: Warwick to Stratford-on-Avon; Birmingham and Wolverhampton, via Stourbridge, Kidderminster, and Droitwich, to Worcester, there connecting with lines to the west and south; Wellington to Market Drayton, and over the North-Westem to Crewe thus securing a ready means of access to Manchester; Ruabon to Bala and Dolgelly, through the delightful scenery of Wales. Besides these, there are others of less consequence, and numerous small offshoots in the Birmingham district, which form a local network. The company are also joint owners with the London and North-Western Railway of certain lines in Wales, over which a through service of expresses runs between Manchester, Liverpool, and the north, and Bristol and the south-west.

Travelling Facilities

Services between Chief Towns. There is such a large number of important towns on the Great Western that perhaps the most concise method of treating the services thereto will be as shown in the concluding table of this section. In discussing the distinguishing features of the three main routes described above, we find that the first has excellent express services; the second, distinctly poor; and the third, tolerably good. Along or adjacent to the first route we have such populous centres or thriving ports as Reading, Bath, Bristol, Weymouth, Taunton, Exeter, and Plymouth. In the annexed summary will be found a succinct view of the facilities afforded by the company to these places. Until two or three years ago this service to the west and south- west was the reverse of creditable, but with the establishment of the 10.15 a.m. down and 7.50 p.m. up, and the removal of third- class restrictions from the two up and down 4^hours Exeter expresses, a marked improvement took place. The popular seaside resorts of Weston, Ilfracombe, Torquay, and the South Devon coast generally, are made readily accessible by these convenient trains. Weston is now within some 3^ hours from London (137} miles) by the fastest train; Ilfracombe (232 J miles) is just over 6 J- hours away; and Torquay (220 miles) 5 hours. Thus, considering their distance from London, these health resorts are by no means badly treated. The service to Plymouth also is a really excellent one, bearing in mind that the Plymouth trains are run for Plymouth alone, there being further west no towns of any importance all the way to that Ultima Thule, Penzance, and this also is still within the reasonable time of 9 hours from Paddington, although in 1891 it could be reached in 8 hours 40 minutes. . . .

The second route is that to South Wales, and, unfortunately for the inhabitants of the southern half of the Principality, it is their only means of access to London. For a long time they were even more neglected than now, and it was not until the opening of the Severn Tunnel that the Great Western thought fit to give these rich mineral districts an express service at all. Undoubtedly, very much greater facilities might be granted, but, there being no competition from London, it seems unlikely that the Paddington management, which is in many respects most conservative, will bestir itself just at present. . . .

Things are a good deal less sluggish on the third main line, that to Birmingham and the North. Since 1890 several really creditable trains have been added, and it is only the most northern points, such as Chester and Birkenhead, which are left out of consideration. Cheltenham, however, which is reached via Chipping Norton Junction, is very badly treated indeed.

Looked at as a whole, the Great Western has a higher reputation for speed with most travellers than it is actually entitled to. Its great faults are the bad treatment accorded to South Wales, and its generally indifferent arrangements for cross-country traffic. In punctuality the line occupies a fairly good place, though the pressure of exceptional traffic throws the company's discipline out of gear, and there is an absence of that strenuous striving after punctuality which characterises the Great Northern and the North Western. . . . . Like most other railways, the Great Western follows a beaten path with its local services. There is no very heavy suburban traffic near London what there is runs punctually and frequently enough. On the numerous lines in the company's extensive district fair punctuality is observed, and doubtless local interests (the importance of which or otherwise we have not attempted to estimate) are duly attended to. The services on some are, perhaps, more or less cramped by single -line working a large portion of the Great Western system being single line.

Rolling Stock and General Accommodation

As regards passenger rolling stock, the Great Western takes rank with the best of English railways. On the main routes, in the London suburban district, and on the principal branches, the carriages are most comfortable, being well cushioned and roomy, and it is only on the less important of the company's lines that we find any really bad coaches. The stock running in the fastest trains compares well with the finest owned by any other railway even the third-class compartments being frequently decorated with photographs of the "beauty spots" on the system. A "Corridor" train has recently been built to run on the Birmingham and Birkenhead line, providing excellent accommodation for all three classes. Most of the main line stock on the Great Western is mounted on eight-wheel bogie trucks, and many of the carriages have the clerestory roof, which, although not favourably regarded by some carriage designers, certainly increases the internal dimensions of the compartment, and gives it a more airy appearance. Gas is being rapidly introduced for the lighting of the carriages.

In other departments also the company merit considerable praise. The line is well signalled throughout, and the brake used is the Automatic Vacuum. The station accommodation on the line is good, and some of the roadside stations near London are models of their kind, many of them being tastefully laid out and decorated with flower-beds.

Locomotives, speed, gradients, and actual performance

The Great Western Railway 3014, a 2-2-2 two-cylinder passenger express engine. Designer: W. Dean

(a) Speed. The greater proportion of the very considerable and highly creditable booked train speeds on the Great Western is concentrated on a comparatively small section of this vast system namely, from London to Exeter, and from Didcot to Birmingham. Elsewhere, on such lines as the South Wales sections, the connections between Bristol and the North via the Severn Tunnel, the line to from Birmingham northwards, the Weymouth section, and on many other parts of the system where an express service is demanded to a greater or less extent, the speed is not by any means high, being generally nearer 40 miles an hour than 45.

(b) Gradients. The Great Western has on the whole an easy track. From Paddington to Bristol the line is nearly level, there being an almost imperceptible rise from London to Swindon, and beyond the worst gradients being 1 in 660 west of Reading, and 1 in 1,320 east of it. After Swindon we have two short but steep descents, 1 in 100, of two miles length each, from Wootton Bassett to Dauntsey, and through the Box Tunnel From Bristol to Exeter the line is again almost level, the only exceptions being a rise and fall between Bristol and Nailsea, and between Wellington and Tiverton Junction. Below Exeter the character of the road changes altogether, curves and gradients are very severe, there being several miles of 1 in 40; while between Plymouth and Penzance matters are still worse. These two last-mentioned sections, however, do not much concern us, as there is but little express work thereon and the same may be said of that portion of the Great Western second main line which lies west of Cardiff, which has some very severe short stretches. The third main line is almost level to Birmingham, with the exception of the Hatton bank (four miles of 1 in 107). North of the hardware centre there are frequent but very short stretches of 1 in 100, and near Wrexham there are four miles of 1 in 82. This, therefore, is a moderately hard section to work.

Among other important parts of the system may be mentioned the Severn Tunnel line and the route to South Wales via Stroud and Gloucester. On the first of these there are several stiff grades (1 in 80), and the Bristol-North expresses have some hard ground to run over. The Gloucester line is rendered difficult by the well-known Brimscombe bank, which ascends steeply on each side of the tunnel near Stroud.

(c) Locomotives, Until May, 1892, the Great Western locomotives were naturally classed as broad- and narrow-gauge. For the broad-gauge expresses the company used the well-known "Lord of the Isles" type, introduced so far back as 1846. There were about 30 of these in use, and the principal dimensions are given below in parallel columns, together with those of some of the latest varieties for use on the narrow gauge, including the new 7-ft 8-in. singles, which have supplanted the broad-gauge type in express work. These broad-gauge singles were, of course, not used on the severe routes in the south-west, saddle-tank bogie engines with 5 ft. 9 in. wheels and 17 in. by 24 in. cylinders taking their place.

Before the abolition of the broad gauge the narrow-gauge expresses were chiefly worked by 7-ft. "singles," with cylinders 18 in. by 24 in., and this class is still extensively used, and gives the very best results. Some of the finest work in England, generally with heavy trains, has been done by them. . . . Of the more recent Great Western locomotives it may be said that they are, in general design, of very striking appearance. There is at present no other company so lavish in the display of the brighter metals in the exterior fittings of boiler, framework, etc., to which we were accustomed on almost every line in bygone days, but which in these times does not seem to find favour on other railways. As in the case of the Great Northern, with its slightly more difficult main-line gradients, the single type of engine is that in general use for the fastest trains, and the new 3,000 class in several respects bears a resemblance to the 7-ft. 6-in. singles of recent Doncaster build. Following the old broad-gauge practice, the newer engines seem likely to be more widely known by their name-plate than their number. Their colours are a dark shade of green above and on wheels, with chocolate-brown for wheel-casing and framing. The brake in use is the Automatic Vacuum.

(d) Actual Performances. The 7 ft single is the only narrow-gauge type that has established for itself any great reputation for excellent work on the Great Western. This class is seen to best advantage on the 4.45 p.m. and other expresses from Paddington to Birmingham and Birkenhead. Many of the trains hauled by them are extremely heavy, and the writer knows of a case in which Oxford was reached in 72 minutes after leaving London (63 ½ miles), with a load of 16 coaches. Mr. Rous-Marten mentions an instance, as showing the work done on rising grades by an engine of this type, of ascending the Hatton bank (four miles of 1 in 107) with 145 tons in 5 minutes.

On the old broad gauge the work done was creditable, though not remarkably brilliant. Time was frequently lost on the fast run from London to Swindon (87 minutes), this being due to the comparatively low tractive force of the broad-gauge "singles." On the return journey, with the road in favour of the train, the booked speed was almost always improved upon, even with the heaviest loads. In fact, the distance has frequently been done in 77 minutes, and once in 76, and it was an everyday occurrence to cover it in 82 to 85 minutes, even with loads equal to 15 or 16 coaches. On up grades, however, the 8 ft singles were rather at a discount, though the work done, considering the dimensions of the class, cannot be called bad by any means. . . .

The Great Western has, in its time, made many record performances. In the palmy days of the broad gauge, when the "Dutchman" was timed to leave Didcot 57 minutes after setting out from Paddington, there used to be some fine running. On one occasion the distance of 53 ½ miles was covered in 47 minutes. This is probably the fastest start-to-stop run ever recorded, but, considering that the load of the train was extremely light, careful observers will rank it below many recent well-attested performances on other lines.

Bibliography

Pattinson, J. Pearson. British Railways: Their Passenger Service, Rolling Stock, Locomotives, Gradients, and Express Speeds. London: Cassell, 1893. Internet Archive version of a copy in the Stanford University library. Web. 26 January 2013.

Last modified 27 January 2013