omen artists of the Victorian period have been enjoying scholarly attention for several decades now but, if that population is broken down by medium, it is soon clear that painters have been by far the greatest beneficiaries of this revisionism. So it is good news indeed that in the last decade or so, female sculptors of the time have been coming into better focus. In 2012, Shannon Hunter Hurtado's Genteel Mavericks: professional women sculptors in Victorian Britain appeared, complemented in 2020 by Pauline Rose's Working against the Grain: women sculptors in Britain c. 1885-1950. A monograph on one of the leading figures in this field, Susan Durant, also by Hurtado, The Company she kept, was brought out in 2013. (Whether Lucinda Hawksley's The Mystery of Princess Louise, published in 2013 by Random House, should be added in here, I leave it to Victorian Web readers to decide for themselves.) Now two established experts on British sculpture, Marjorie Trusted and Joanna Barnes, have edited a collection of essays which, while covering a broader field than Victorian Web claims as its own, contains much of interest to the Victorian Web community that will further consolidate this topic.

Discovering Women Sculptors arises from a series of on-line lectures taking place in 2021 and 2022 instigated by the Public Statues and Sculpture Association (PSSA), a UK organisation devoted to what its title says – and this book is a manifestation of its commitment to inform and educate, not just to preserve and agitate. While its sixteen essays are all interesting, covering artists working from the first half of the 17th century to the second half of the twentiethth century, this review will concentrate on those aspects of the book that fall within the Victorian Web's time-line.

The aforementioned Pauline Rose provides an introduction to the book, well read and well argued, which looks into how and why female sculptors had difficulties c.1880- c.1930 in taking up their chosen art, prosecuting it and succeeding with it. She points to a watershed project, the on-line database "Mapping the Practice and profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951," set up in 2011 by Ann Compton, Marjorie Trusted and Alison Yarrington under the aegis of the University of Glasgow, which revealed that about one third of the practitioners' names collected there were female. Some of these already had a little "tail" to them (Ruby Levick, Margaret Giles), others none; few indeed had a visibility of any substance (Kathleen Scott).

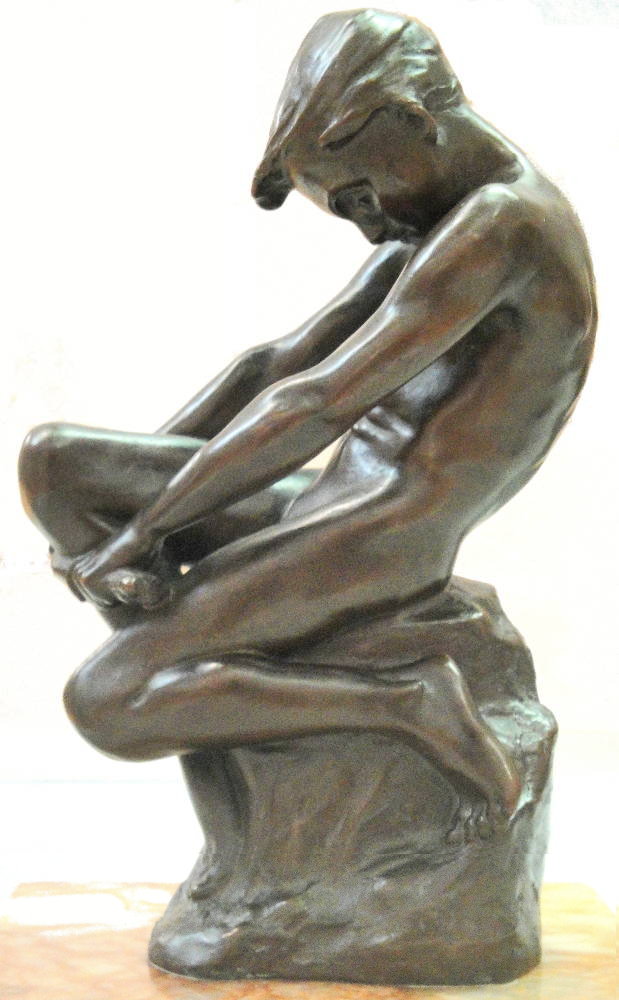

Left to right: (a) Susan Durant's marble relief of Prince Leopold (1853-1884), c.1866, in the Albert Memorial Chapel, Windsor. (b) Ruby Levick's Wrestlers, 1897, from the Studio. (c) "He shall give his angels charge over thee" by Margaret Giles, 1898. [Click on all the images for more information.]

Chapters follow which are largely monographic, intended to introduce a figure who will be new to the reader or to fill out a figure about whom a negligible amount has been known before now. In chapter four the reader meets Marcello (1836-1879) – real names Adèle d'Affry and later Duchesse de Castiglione Colonna – whose name flits through the history of Victorian art but whose career is here recounted in detail by a descendant, Magnus von Wistinghausen. Several European artists did make a name for themselves in Victorian Britain – the French painters Edouard Frère and Rosa Bonheur come readily to the mind, along with the Italian sculptor Carlo Marochetti – and Marcello drew the attention of British critics and gallery-goers at the 1866 Royal Academy exhibition with her bronze bust The Gorgon, which is now in the collections of the V and A Museum. A second sensation was her full-length bronze Pythia (1870), described here as her "undisputed masterpiece". Dividing her time largely between her birthplace Fribourg, Rome and Paris, Marcello remained something of an exotic outsider to British art-lovers, but a ground-breaking artist to the French.

Chapter five (though it would have made more sense for this to precede the essay on Marcello) has as its protagonist Félicie de Fauveau (1801-1886), whose work Philip Ward-Jackson analyses soberly for its contributions to three-dimensional Romanticism, even though she is more often just footnoted as a privileged eccentric. Her monarchist, Catholic art may well have been possible only because of its maker's aristocratic circumstances, but its position well outside the mid-nineteenth-century market-place (her work was not for sale but rather a declaration of values) should not render it invisible to posterity. Invisible in a literal fashion it is likely to be to most of us, however, as her finely-worked marble pieces are nowadays nearly all either in the vaults of the Louvre or private collections.

Two further artists who were marginally known in Victorian Britain occupy Melissa Dabakis in chapter six. Of these, Harriet Hosmer (1830-1908) became a much better-known quantity than her compatriot Louisa Lander (1826-1923). These Americans belong in the "white marmorean flock" (Henry James's famous label for them) that has received deserved but belated attention from US art historians since feminism dismantled the canon, but only Hosmer made an impression on the London public. She was touted in Britain as a type of the new woman who, like Bonheur, paid no mind to outworn traditions that limited what a woman could do with her talent; and attracted considerable attention as the protegée of the classical British sculptor John Gibson and the close friend of both Brownings. While minor marbles such as Puck (1855) became popular amongst her upper-class patrons, her reclining Beatrice Cenci (at the 1857 Royal Academy exhibition) was much talked about and her full-length statue of Zenobia was a sensation at the International exhibition in London in 1862. It was these women's ambition as much as their achievement that put them into the limelight as the "woman question" raged.

Harriet Hosmer's Zenobia, shown in London in 1862.

Queen Victoria's fourth daughter Princess Louise (1848-1939) comes next into view, as Désirée de Chair seeks to rescue her from her anomalous - might one say, unique? - position and range her somehow alongside other artists of the time. Although she was trained by Durant, Thornycroft and Joseph E. Boehm – professional artists – she could not be treated by the contemporary press as just another aspiring sculptor of the day, although one wonders if a pseudonym would have helped with that. A good job is done here of putting her oeuvre before the reader, although the question of her work's merit is still open, in my view.

Philip Attwood's chapter is on a number of women working in a particular branch of sculpture, the medal; his subjects include Ella Casella, Elinor Hallé, Effie Stillman, Ethel Bower, Feodora Gleichen and Mary Gillick. If sculpture is a kind of art that challenges many people's technical knowledge, surely medal-making is even more so, and this essay would have benefited from more explanation of the essentials. For instance, early on Attwood makes much of the difference between a medal that is struck and one that is cast, but gives the reader no assistance in understanding the distinction. Equally, what was the significant difference, at this time, between medals and coinage? The work of these women, to a large extent products of Alphonse Legros's influence on the Slade School, ranges from c. 1880 to c. 1950, so it can be seen that Attwood covers a lot of ground, and readers will want to search out further information on these intriguing figures.

The Stick by Gwendolen Williams, before 1914.

Gertrude Williams (1877-1934) and Margaret Butler (1883-1947) are the subjects of chapters nine and ten, written by Phyllida Shaw and Mark Stocker respectively. Examples of very able and committed artists who, nevertheless, occupy few column inches in the record of late-Victorian and early-twentieth-century sculpture, their stories illustrate how merit alone does not produce fame, never mind reputation. For Williams, beginning in Liverpool, spending time in Paris, then adopting Scotland as her base of operations after marriage (Williams is both her maiden and married name), the lasting testament that a sculptor can achieve – public work – was attained but ironically by its very nature did little to promote her name: for war memorials (of women's work for the Imperial War Museum, 1919; for Queenstown, South Africa, 1922; for Paisley, 1922-4; and Edinburgh Castle, 1922-7) seem to require their makers to don masks of modesty so as to give all the attention to the memorialised victims. In Butler's case, a foray to Paris from her native New Zealand may have been the making of her, but her return to her homeland, parochial, culturally gauche and of limited means, doomed her career to anti-climax. If sculptors cannot make good work without ability, they will not make careers or reputations without the right circumstances, and this especially so for women.

This valuable and fascinating book adds to the growing library on women sculptors and their work, is handsomely designed and produced (albeit with monochrome illustrations, that are rather on the small side), and is also very good value.

Links to Related Material

- Victorian and Edwardian Women Sculptors

- Review of Pauline Rose's Working Against the Grain: Women Sculptors in Britain c.1885-1950

- Zoë Thomas's Women Art Workers and the Arts and Crafts Movement [Review]

- Victorian Women and the Visual Arts

Bibliography

[Book under review] Rusted, Marjorie, and Joanna Barnes eds. Discovering Women Sculptors. Watford: PSSA, 2023. Paperback, £20.00 ISBN 978-1-8383976-3-0

Devereux, Jo. The Making of Women Artists in Victorian England. Jefferson: McFarland and co, 2016: 134-63.

Hawksley, Lucinda. The Mystery of Princess Louise. New York: Random House, 2013.

Hurtado, Shannon Hunter. Genteel Mavericks. Professional Women Sculptors in Victorian Britain. Bern: Peter Lang, 2012.

Hurtado, Shannon Hunter. The Company She Kept. Manitoba: University of Manitoba, 2013.

Rose, Pauline. Working Against the Grain. Women Sculptors in Britain, c. 1885-1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020.

Created 9 February 2024