This item is a clipping in the archive of St Augustine's church. It gives a wonderful insight into the Victorian mindset. Is it reverential, as might first appear, or is it humourously ribbing the locals and their airs and graces? Maybe it's both. At any rate, it is an excellent observational narrative of days long gone, which I hope modern-day readers will enjoy. — Stephen Hartland, Churchwarden Emeritus, St Augustine of Hippo, Edgbaston.

It was in the year of grace eighteen-hundred-and-seventy-six that I first discovered that Edgbastonians were not Birmingham people. All who have travelled in Germany will remember how frequently and carefully certain books must be filled up with visitor's name, home, business, and destination. And when giving the necessary particulars to the sentry at the fortress of Ehrenbreitstein observed under the name, occupation and residence the signatures of a well-known family which, mutato nomine, ran thus:- J. Brown, Gentleman, Edgbaston; Mary Brown, Edgbaston; J. Brown, Junior, Gentleman, Edgbaston. An experienced friend assures me that the same custom is traceable all round the globe, and that the Edgbastonians are usually careful to eschew the name of Birmingham for reasons which, no doubt, are satisfactory to themselves.

The inhabitants of Edgbaston - Edgbasston they call it - are IN EVERY WAY SUPERIOR to other people of the neighbourhood. They are better bred, more highly educated, more fastidious in their eating. Vulgarity and pride of purse are totally unknown, and all are legibly stamped with the caste of Vere de Vere [the de Veres were an aristocratic family, a representative of which is castigated for her pride in Tennyson's poem, "Lady Clara Vere de Vere"]. They live in an atmosphere of Liberty silks and blush roses. They speak in voices of exquisite sweetness. The Edgbaston "tone" is recognised and valued in every debating society worthy of the name. The atmosphere of Edgbaston has had a powerfully elevating influence over the neighbouring city, which is proud of its juxtaposition to so much culture and thankful for the privilege. Other suburbs have thought to rival Edgbaston, but the dwellers therein could not acquire the "tone," the je ne sais quoi, of Edgbastonia; they could not exist with such refinement, neither could they die with equal decorum, and while a weary Handsworth and Harborne have long relinquished this unequal contest, a panting Moseley still toils on in vain. So that in visiting Edgbaston I may be excused a little trepidation, a kind of nervousness, a sort of diffidence arising from a sense of personal unworthiness.

Years had elapsed since last I gazed upon THE SPLENDOURS OF THE HAGLEY ROAD Living in a comparatively low quarter affected by artists, authors, editors, and other members of the dangerous classes, I was quite out of training, and the aristocratic air of Edgbaston proved almost overpowering. Everybody was going to church. Crowds of well-dressed people moved briskly in every direction with the decided step and serious air of people having a definitive object. Richly-robed ladies hung on the sleeves of elegant coats. Sprightly old gentlemen chatted merrily with pretty young girls. White-haired ladies walked with their niece, daughter or "Ladies" companion. Two-by-two the pupils of a Ladies school passed demurely by with regulation downcast eyes. Three Edgbaston Yum-yums [Yum-Yum is the female lead in Gilbert and Sullivan's operetta, The Mikado], with the same rapid, easy swinging walk and with the same Oriential magnificence attracted especial attention pulled me up short. They marched like three circus ponies. This extraordinary parity might be accidental, but was, more probably, carefully pre-meditated. Such cases of malice aforethought are not altogether unknown. The lady who dismissed the dark-complexioned lover, and married the red-headed man because he went better with a wedding bonnet, choosing a suitor to suit her dress, is the leading case in point.

Reflecting deeply on these insoluble mysteries, I reached the church at last AND WHAT A BEAUTIFUL CHURCH IT IS.

Beautiful both inside and outside, perfect in proportion, at once symmetrical and substantial, massive and graceful, chaste but not cheap, lavishly decorated but not vulgarly overdone. The setting sun shining through the stained windows enhanced the beauty of the interior, and music soft and slow, inspired devotional feeling. The church was already full, or seemed so, but a number of people still blocked the entrance, waiting for accommodation. A beadle who looked like a bishop in disguise, bustling as a bumble-bee, courteous as a cardinal, explored the church, buzzed into unknown cracks and crannies, dragged secret sittings to the light of day, and triumphantly bore away the waiting worshippers. A splendid beadle, light as air, smiling as sin, swift as a greyhound, mobile as a rattlesnake, A VERY PRINCE OF BEADLES. His speed was most surprising. His presence pervaded the place. If ever a man could be in two places at once, it is that beadle. To watch him make his laps was to snatch a fearful joy. You saw him the chancel - presto, he was at the west end. You lost him in the opposite transept - lo, he was at your shoulder. He was hic et ubique, like the Ghost in Hamlet. Like Will-o'-the-Wisp, he might sing, "I'm here, I'm there, I'm everywhere, Who tries to catch me catches but air." By my halidome [an old word meaning "sanctuary" or "holiness"], a most potent and goodly beadle, I do protest and declare.

The assembled people were not only better dressed and better looking than the average city congregation, but seemingly about a foot taller. They were fairly well-behaved for a fashionable audience, but their demeanour in the matter of devotion and reverence for the House of God was not at all comparable to that of poorer folks. There was too much conversation, too much merely mundane criticism. The music was heard rather as an exposition of art than as a devotional exercise. And the verdict of some connoisseurs was audible both before and behind. They seemed to be speaking to the gallery with authority, and reminded me of Count Fosco [a larger-than-life Italian spy in Wilkie Collins's novel, The Woman in White], who indicated when the opera singers should be encouraged, and waved his hands deprecatingly when people applauded at the wrong time. The music was very good. The versicles and canticles were given in perfect style. The psalms were sung with tremendous impulse and power. The anthem, from the Twelfth Mass of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, was the ever-popular Kyrie Eleison, to which was added the undying Gloria in Excelsis Deo. The choir acquitted themselves grandly in both movements, the bass solo of Mr. Wilks and the exacting part allotted to the trebles being especially well done. The rallentando which concluded the "Gloria" is not in Mozart's score; but doubtless Mr. Gaul knows best. Many prefer a pious adherence to the master's text, others prefer to bring him up, or down, to date. John Hullah tells a story of country choirmaster who boasted that his choir sung Handel. "Don't you find him difficult?" said Hullah. To which the answer came, "Sometimes we does, BUT THEN WE HALTERS 'IM."

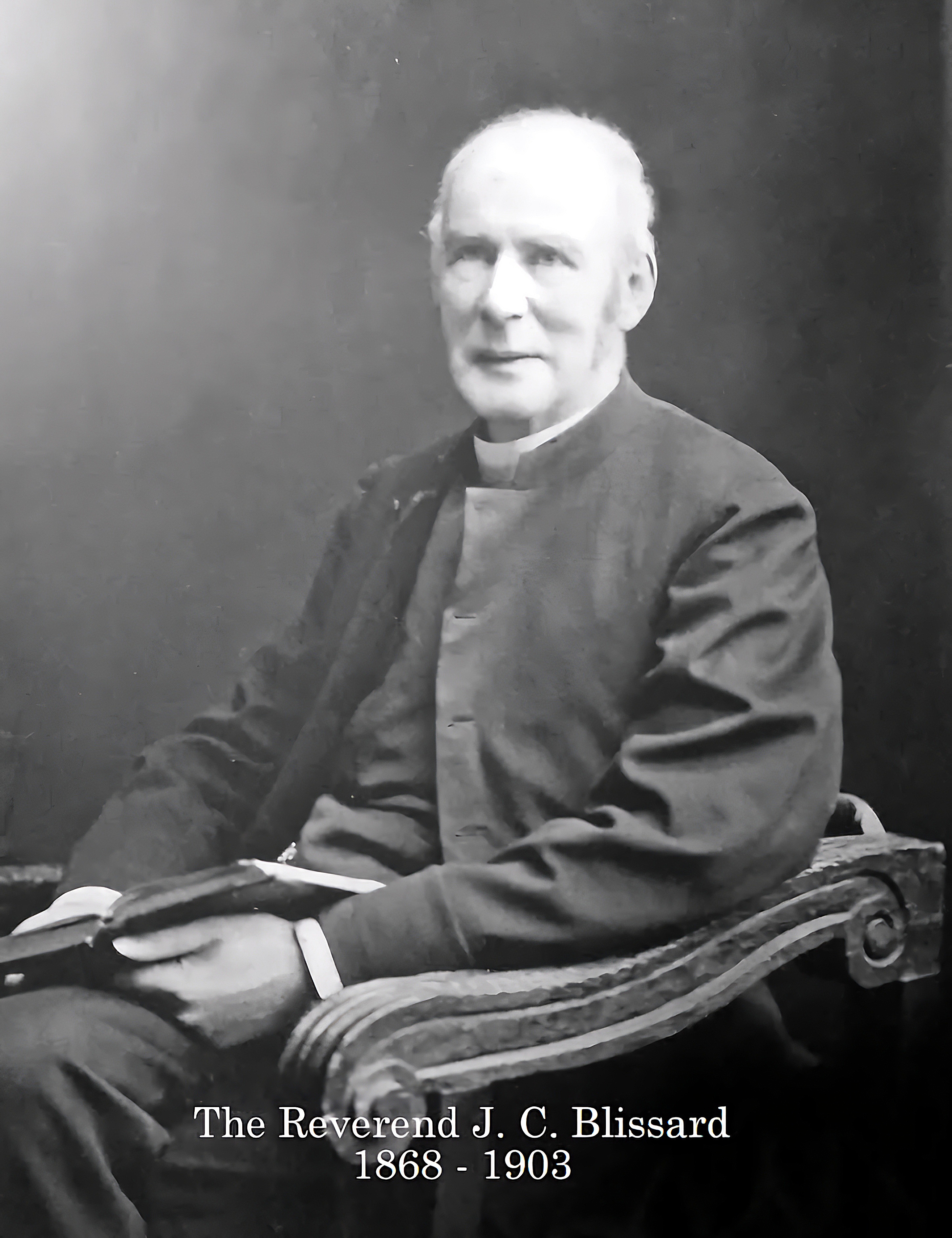

The Reverend J. C. Blissard, M.A., preached a short and simple sermon from the Fourth Verse of the Fourth Psalm, Prayer Book Version – "Stand in awe and sin not; commune with your own heart, and in your chamber, and be still." The deceitfulness of the human heart was first dealt with. Then the earthquakes of the kindly air of a father speaking earnestly to his children. There are many sorts of sermons shallow, deep, plain, ornate, simple, sensational, tricky, sincere, anecdotic, idiotic; sermons constructed to display the preacher's learning, eloquence, rhetoric, controversial power, and sermons composed for their proper end. Sermons of the best and truest sort may differ widely in character, and I, FOR ONE, CAN ADMIRE THEM ALL.

An elaborately wrought thesis is good, a simple exhortation is also good, may be equal as artwork, and may be superior in result. When the preacher's heart is right, the sermon seldom goes wrong. Mr. Blissard does not astonish you, but you leave the church with a profound respect for the preacher, and with a disposition to bear in mind the teaching given with such unaffected simplicity, such gentle and persuasive earnestness. Mr. Blissard can be profound if so minded. He has published a book or two, which favourably exhibit his powers as a deep and earnest thinker. His repute as a mathematician is considerable, and the deep-set lustrous eyes, kindly though keen, betoken the powerful and penetrating intellect behind. Mr. Blissard came to Edgbaston in 1862, and immediately took root. He has been Vicar of St. Augustine's since the church was built, in 1868, and if his parishioners can rule, he will end his days among them. For Mr. Blissard is universally esteemed. Men who dislike and revile the clergy on principle gladly include him in their brief list of exceptions. Boswell has recorded how a little girl, sitting on Dr. Johnson's knee, said, "I don't like John Bunyan," upon which the great lexicographer at once set her down with "Then I don't like you." It would be wise to follow a similar course with any one who avowed dislike for Mr. Blissard. But the existence of any such malcontent is ALMOST INCONCEIVABLE.

There was a choir rehearsal after service, and some of the boys whose voices verged on the raucous tones of manhood, and who were perforce compelled to bid farewell to their companions, were presented with splendid books, handsomely bound British classics, each with a beautifully illuminated inscription, bearing the names of vicar, wardens, and organist – books to be proud of, inscriptions to be treasured for evermore. Verily the lines of the Augustinian have fallen in pleasant places. Everybody is prosperous, happy, and content. The worshippers move in an atmosphere of beauty. The church itself, its music, its officers, its surroundings, are agreeable, delightful, satisfactory, verging on perfection. The great Cardinal Rospoli [Cardinal Bartolomeo dei Principi Ruspoli (1697-1741)] kicked at dying, and his confessor would fain have consoled him by enumerating the delights of Paradise. "Father," said the dying man, "the Rospoli gardens [wonderful Renaissance gardens at Castello Ruspoli, northern Lazio] are good enough for me." People who live in Edgbaston, and attend St. Augustine's Church, may be reasonably suspected of entertaining some such sentiment as this.

Clipping and out-of-copyright photographs kindly provided by Stephen Hartland, with formatting, links, and notes in square brackets added by JB.

Bibliography

"Pulpit and Pew (by our own Visitor), Third Series. No. 61.—St Augustine's Church." Birmingham Weekly Paper. 9 July 1892.

Created 30 December 2024