When I graduated from Glasgow University in 1951, my parents followed the then common practice of having a graduation portrait made of me dressed in (rented) academic gown and holding my diploma. To this end I was sent off to the studio of T. & R. Annan in Sauchiehall Street in the heart of the city. Some years later I became aware of the most admired of the photographic works of Thomas Annan (1829-1887), who had founded the firm in the 1850s, namely, his still frequently cited and reproduced images of the slums of Glasgow — The Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow (1871). As a native Glaswegian, once I learned about Princeton University’s treasure trove of early photographic albums by Annan I could hardly pass up this opportunity to spread the word about his. I offer here a brief introduction to Annan and a cultural historian’s consideration of his most important work, The Old Closes and Streets.1

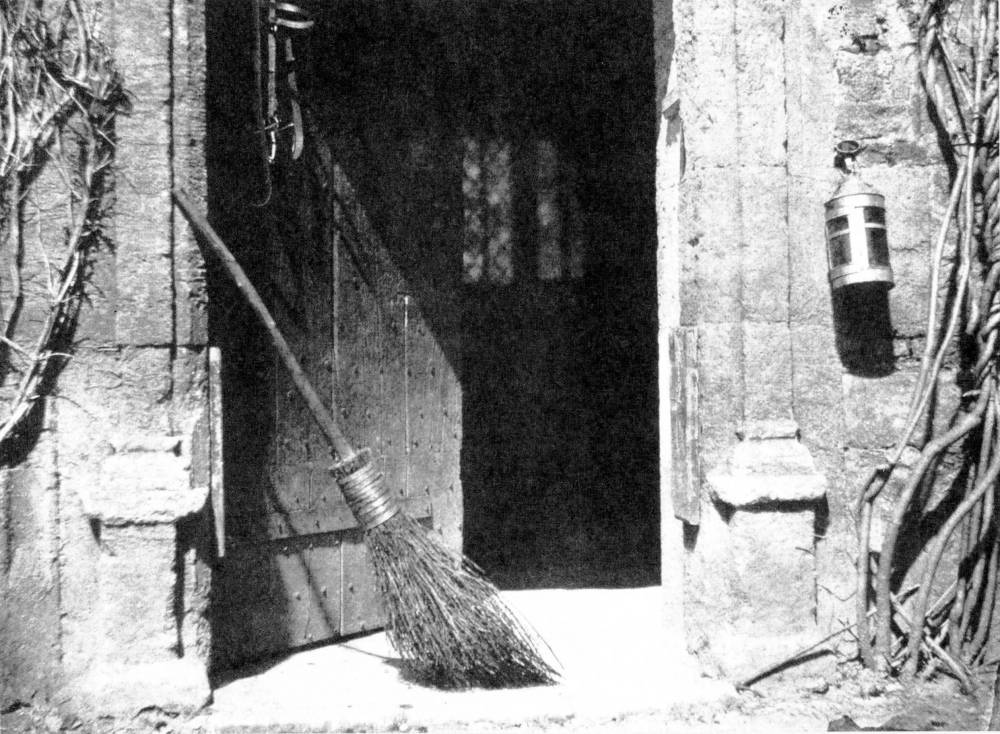

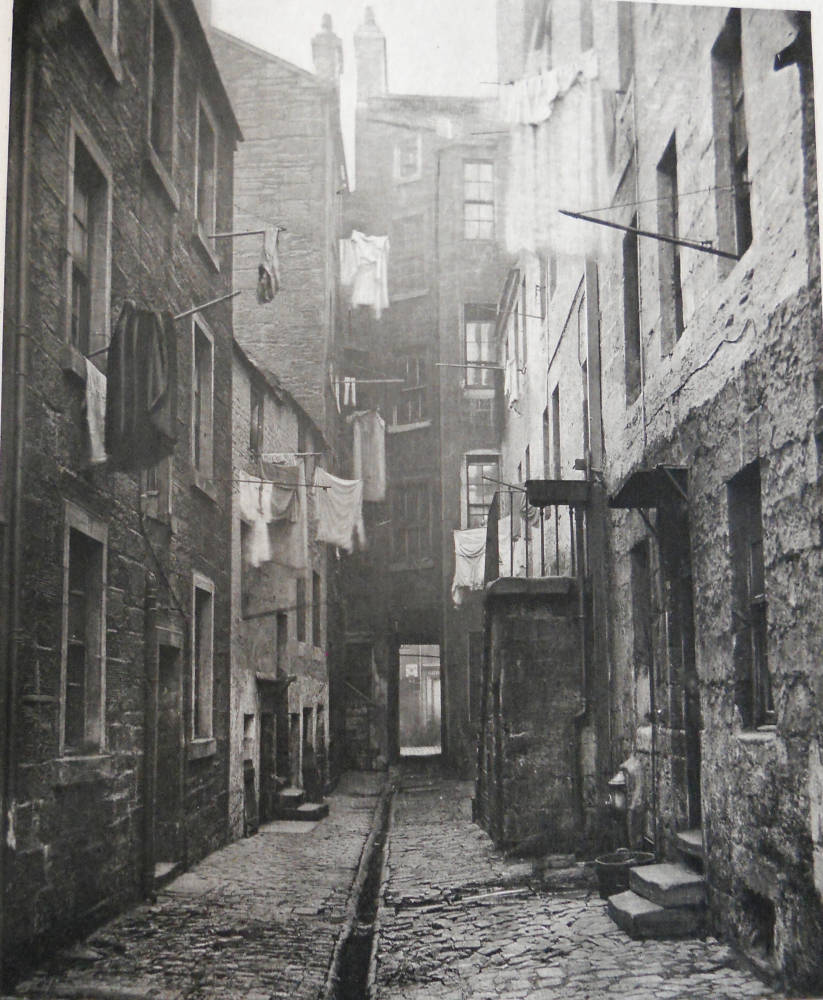

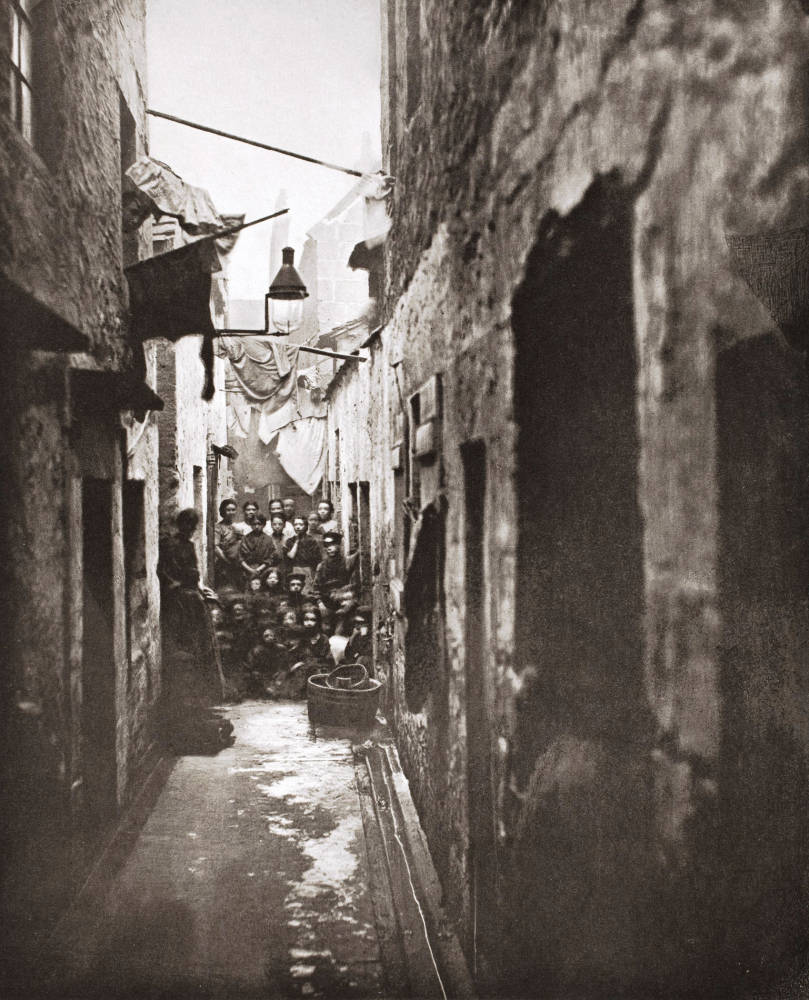

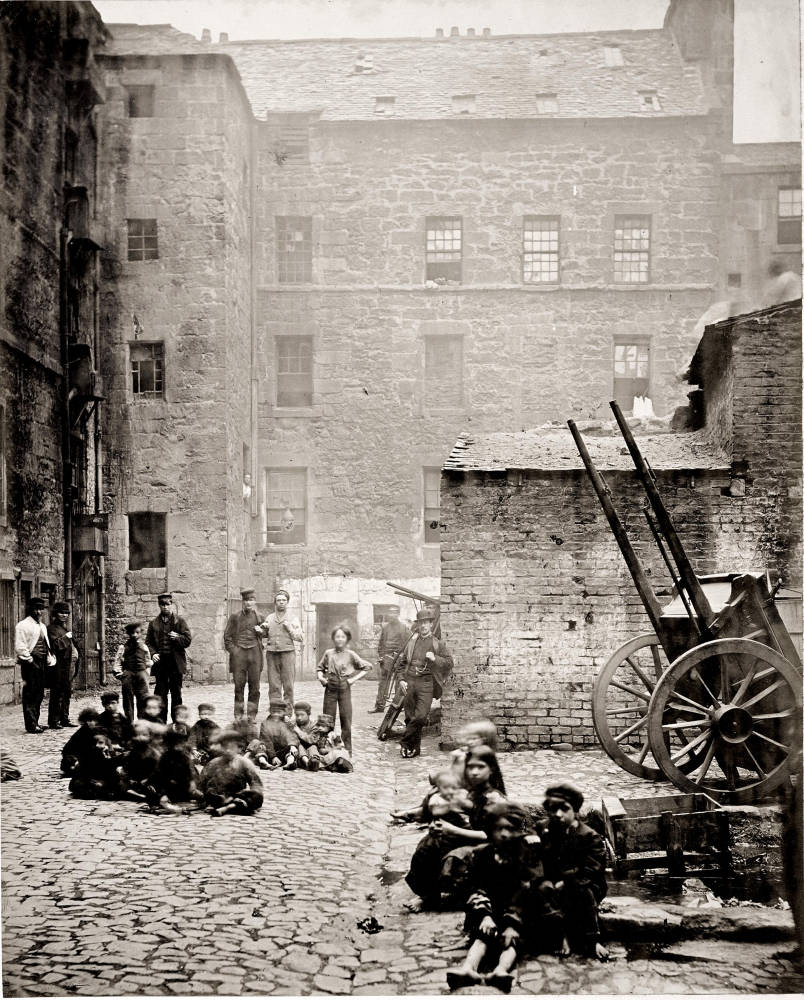

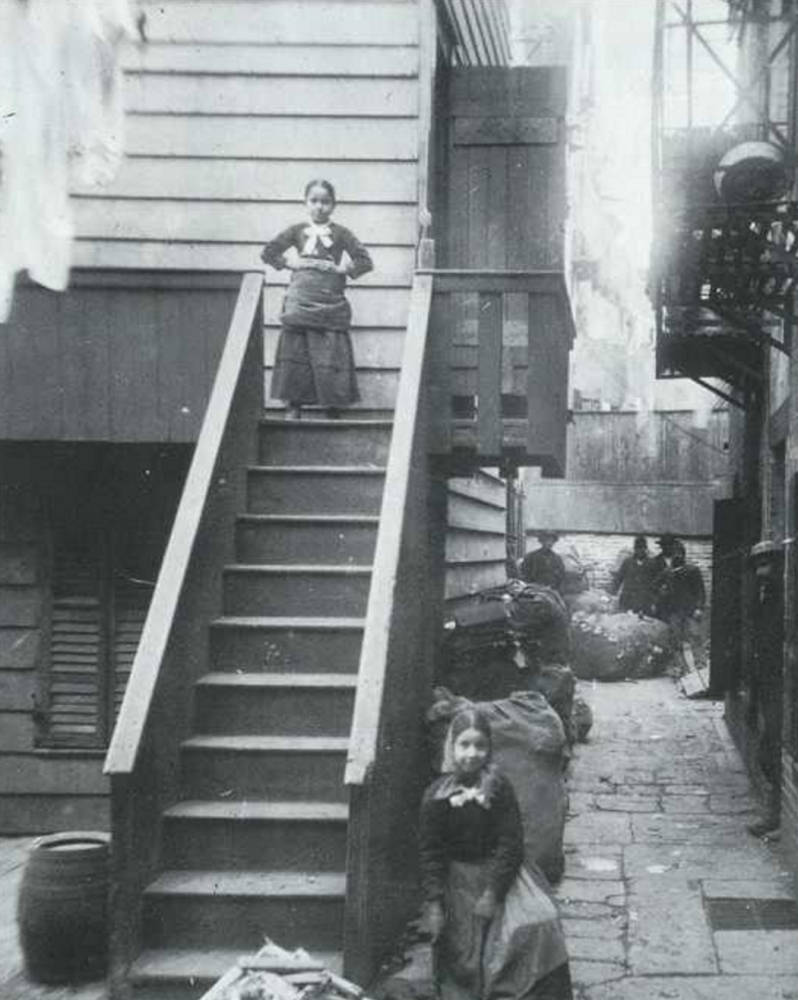

A sampling of Annan's work in The Old Closes and Streets, which will be discussed in a a later section of the essay: Figures 36, 39, & 41: Left: Old Vennel off High Street. Middle: Close, No. 28 Saltmarket. Right: Close, No. 46 Saltmarket.

Though not numbered in the ranks of the most celebrated photographers of the nineteenth century — Nadar, Roger Fenton, Julia Cameron — Thomas Annan was one of an impressive cohort of early Scottish masters of the young medium. To mention only a few of those who made photography their profession: the team of David Octavius Hill (1802-1870) and Robert Adamson (1821-1848), pioneers of the calotype; George Washington Wilson (1823-1893) and James Valentine (1815-1879), who established world-wide businesses in landscape photography and picture postcards; Alexander Gardner (1821-1882), who emigrated at age thirty-five to the United States and was employed by Mathew Brady in photographing the Civil War; Robert MacPherson (1814-1872), known for his photographs of ancient and Renaissance Rome and the first photographer permitted to photograph in the Vatican; William Notman (1826-1891), who became the leading Canadian photographer of his generation; William Carrick (1827-1878), the classic photographer of mid-nineteenth century Russia; and John Thomson (1837-1921), famous for his photographs of the Far East and of London street life. In addition, there were many amateurs, among them the remarkable Lady Hawarden (1822-1865), born near Glasgow as Clementina Elphinstone Fleeming, whose imaginative photographs of girls and women won prizes at major exhibitions in London. (Fig. 5)

Born in 1829 into a farming and flax-spinning family in Dairsie, Fife, in the East of Scotland, Annan joined the local Fife Herald newspaper in 1845 as an apprentice lithographic engraver. On completion of his apprenticeship, he moved to the city of Glasgow in the West of Scotland, already well on its way to becoming an industrial powerhouse, the “Second City of the Empire.” There, on the strength of a glowing reference from the Herald, he obtained a position in the large lithographic establishment of Joseph Swan, who had set up in the city in 1818 and developed a thriving business in illustrations for mechanical inventions, maps for street directories, bookplates, and, not least, books on Scottish scenery illustrated by engravings of landscape paintings. Over the next six years Annan honed his engraving skills at Swan’s.2

In the mid-1850s Annan decided to set up in business on his own. By this time, however, the rapid rise of photography on a commercial scale had led to a significant drop-off in the lithographic trade. In addition, Annan may well have doubted that he could compete in lithography with his well-established former employer. Probably for both reasons, he decided to switch fields and explore the possibilities of photography, where the daguerreotype, introduced in 1839, was being increasingly replaced by a completely different process based on experiments conducted in 1834 by the Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot and much improved by him in 1841. Unlike the daguerreotype, which had no negative and produced only a single, extremely detailed image, Talbot’s calotype allowed for the production of multiple images from a single negative.3 Moreover, some photographers and critics believed that the calotype gave more scope to the photographer than the daguerreotype, which in their view was too precise and thus “could not record the sentiments of the mind,” that is, it left no room for the insights and imagination of the photographer.4

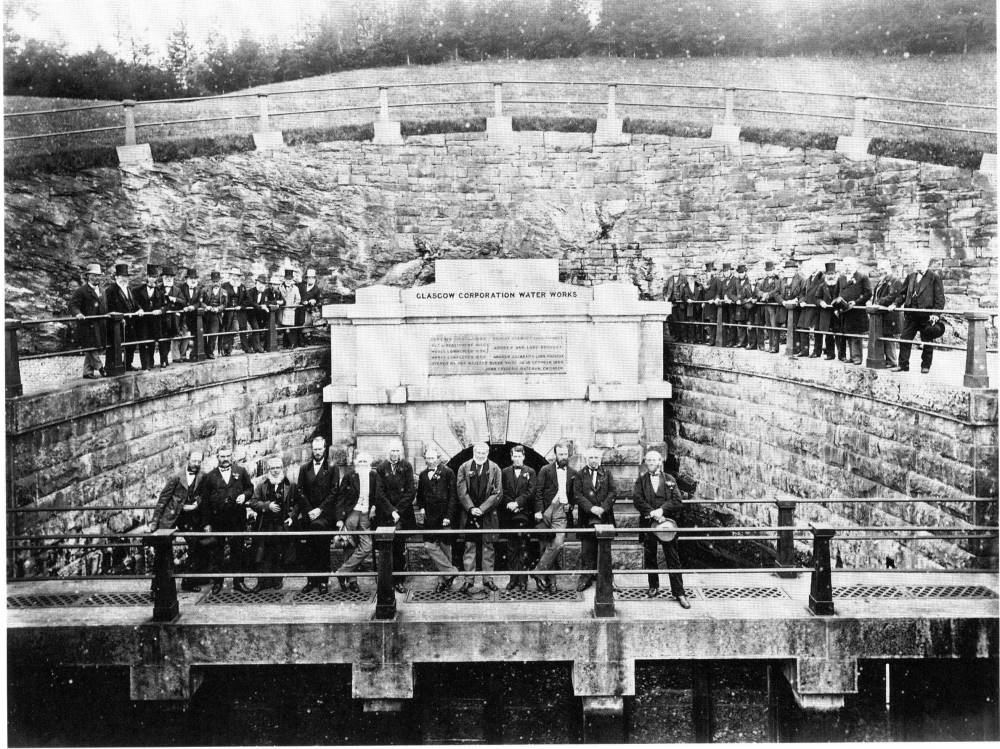

Annan soon established a solid reputation as a portrait photographer (Figs. 6-7), an architectural photographer, a landscape and cityscape photographer, and, in particular, a photographer of paintings.5(Fig. 8) While he turned out many portraits in the new and popular “carte de visite” and “cabinet” formats, as well as landscape and cityscape photographs for books on Scottish scenery,6 (Fig. 9-13) his most important work resulted from commissions to produce photographic records of major civic construction projects, of buildings slated for demolition, and of country manor houses threatened by the inexorable expansion of the city. His first significant publication, Views on the Line of the Loch Katrine Water Works (1859), was commissioned by the Glasgow Town Council’s Water Committee. It presents images not of the Romantic scenery usually associated — thanks in large part to Walter Scott’s Lady of the Lake — with Loch Katrine and represented in countless paintings, drawings, and photographs of the time, but of one of the nineteenth century’s most ambitious civil engineering projects, together with on-site group portraits of the municipal committee charged with overseeing its construction.7 (Figs. 14-16)

Figures 9 & 10. Left: Glasgow Corporation Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1886. Right: Glasgow Water Commissioners at Loch Katrine, 1878.

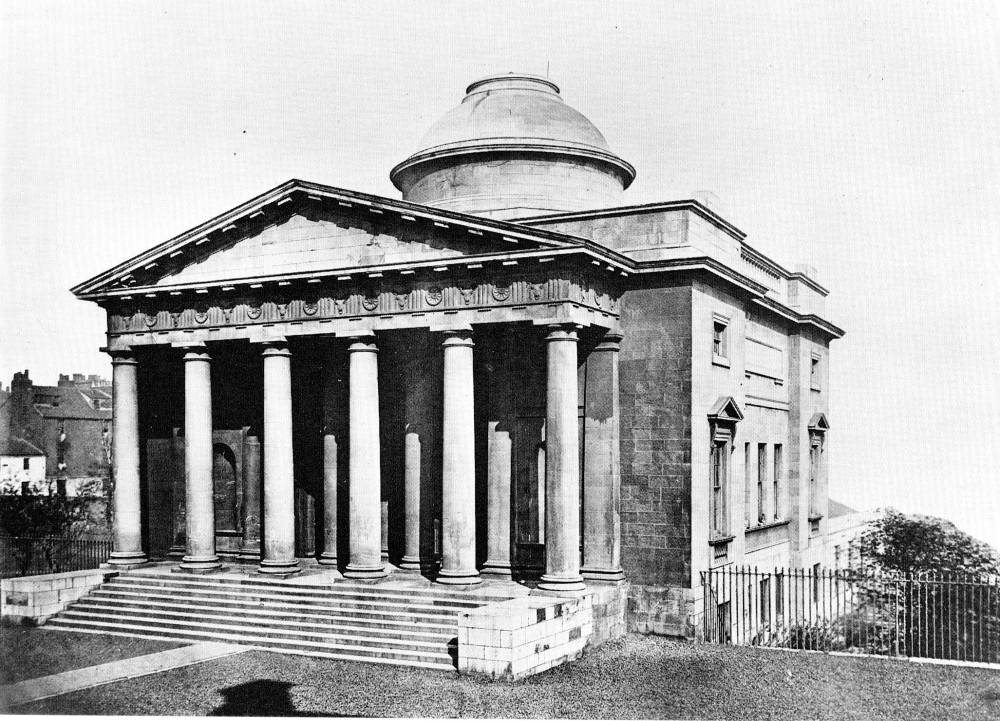

Another official commission resulted in an album of Photographs of Glasgow College (1866) — subsequently bound and published for the University as Memorials of the Old College of Glasgow (1871)

Figures 18 & 19. Left: Professors’ Court. Right: Hunterian Museum.

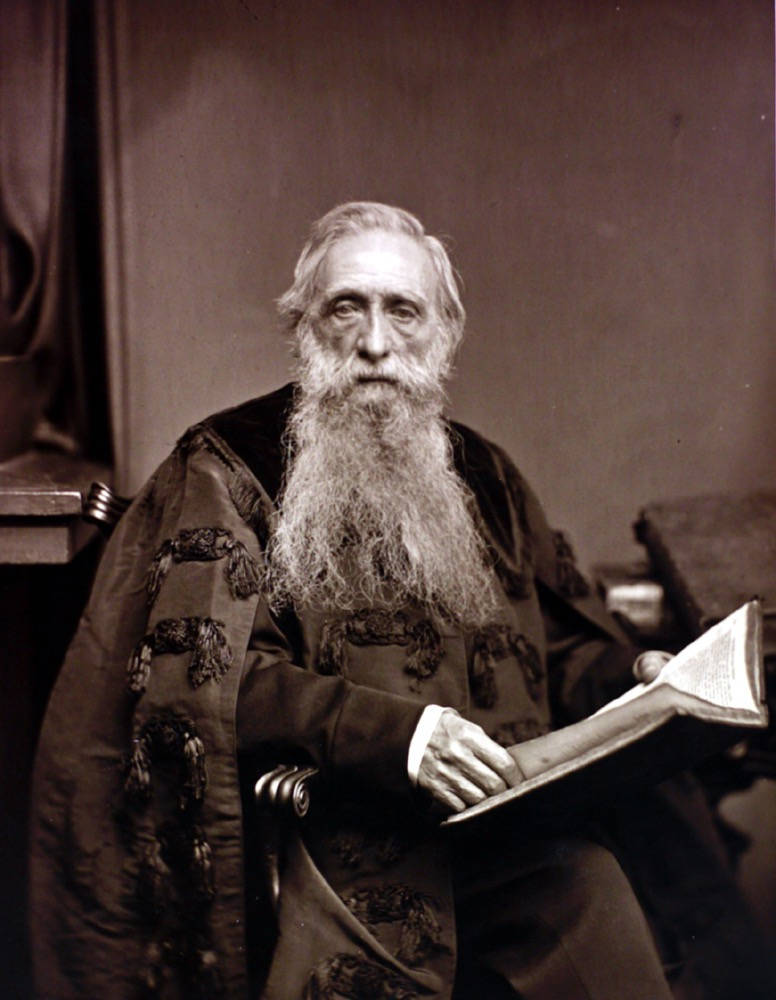

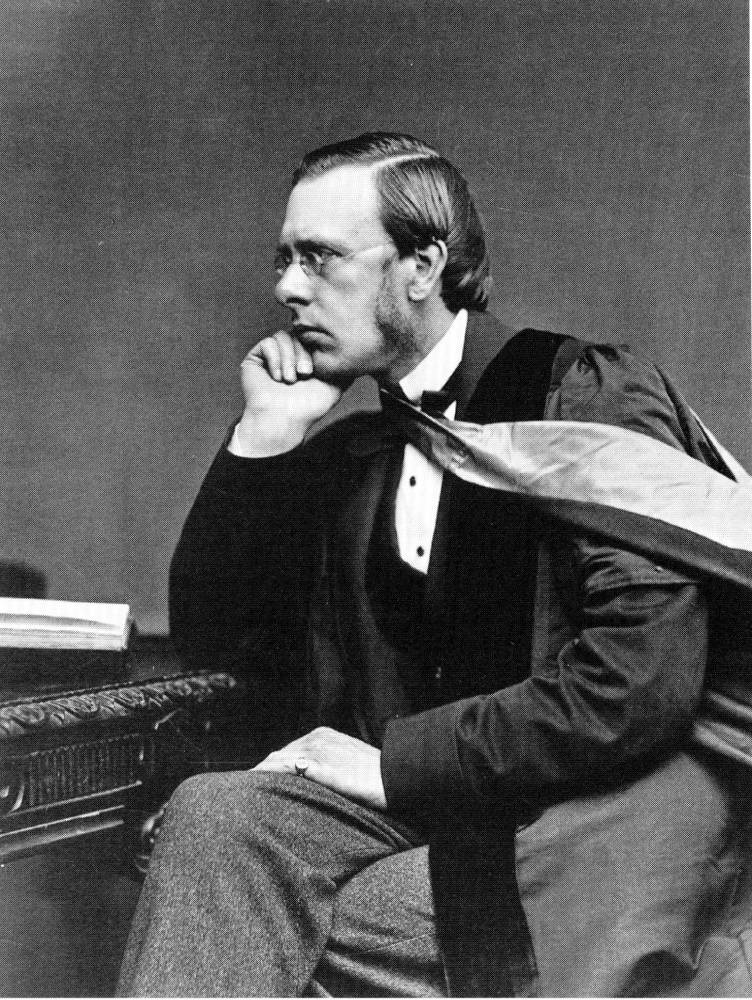

This collection Annan’s photographs contains many fine photographs of the seventeenth-century courts and buildings that were slated for demolition as the university, engulfed by the city’s slums, moved to a new building in the fashionable park-like West End, as well as twenty-six full-page portraits of the Principal and the professors. (Figs. 17-21)

Figures 17, 20, & 21. Left: he Outer Court with the great stair leading to the Fore-Hall. Middle: Portrait of Thomas Barclay, Principal of Glasgow University 1858-1873. Right: Portrait of William T. Gairdner, Professor of the Practice of Medicine.

Two volumes containing handsome, large photographs of manor houses in the vicinity of Glasgow and in nearby Ayrshire (Old Country Houses of the Old Glasgow Gentry (1870); Castles and Mansions of Ayrshire (1885) resulted from commissions by the editors of the volumes and the chief subscribers, namely, the property owners and their families and friends, virtually all of them members of the landed aristocracy or of the old merchant patriciate that was being displaced as the city’s ruling class by new industrial entrepreneurs. (Figs. 22-25)

Figures 22 & 23. Left: Bedlay. Right: Craighead.

Figures 24 & 25. Left: Hunterston Castle, West Kilbride. Right: Mount Charles.

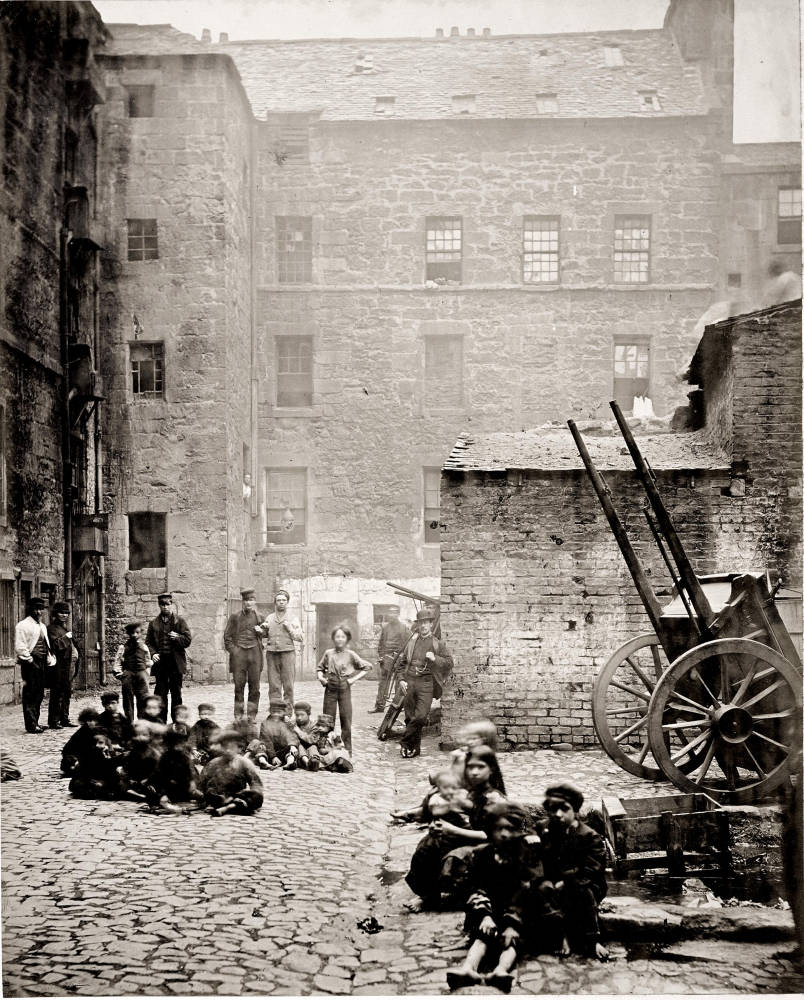

Annan’s best-known, most widely admired, and also most problematical work is the collection of photographs entitled The Old Closes and Streets of Glasgow. These too, judged by many scholars to be the first “social documentary” photographs, were the product of a commission, in this instance from the City of Glasgow Improvements Trust, an agency of the Town Council. The trust had been set up to oversee the demolition, authorized by an act of Parliament in 1866, of a section of the old center of the city — in effect, a substantial part of what Glasgow had been in Adam Smith’s day. This essay will address issues raised both by Annan’s work itself, which is still subject to divergent interpretations, and, more generally, by the genre of documentary photography, to which it is usually assigned.

The Hideous Slums of Glasgow

First, some consideration of the conditions that led to Glasgow Town Council’s commissioning The Old Closes and Streets. Thanks to expanding trade with the New World and the rapid development of cotton spinning and tobacco processing in the eighteenth century and of iron foundries, shipbuilding, locomotive construction, and the chemical and machine industries in the nineteenth, the population of Glasgow had grown from 15,000 at the beginning of the eighteenth century to 100,000 in 1811 and 300,000 by the date of Friedrich Engels’s Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844 (published in the original German in 1845).8

Immigration from the Scottish countryside and especially from Ireland was both a condition and a consequence of the city’s rapid industrialization and expansion.9 The result, however, was the transformation of much of the old town — as most of the better-off residents and then the municipal offices moved away — into a hugely overcrowded, fetid, dangerous, and disease-ridden slum. Exploiting the desperate needs of impoverished immigrants, landlords turned the old multistory buildings into warrens of small, usually one-room apartments and, to make matters even worse, crammed the former yards or gardens between them with additional gerry-built tenements.10

There are many harrowing contemporary descriptions of conditions in the slums of Glasgow in the mid-1800s. It is worth quoting from a few of them to convey an idea of the problem that prompted the city fathers to seek authority to purchase and demolish entire neighborhoods. In a report presented to the House of Lords in 1842, Edwin Chadwick, secretary to the Poor Law Commission, wrote that it appeared to him and his colleague, Dr. Neil Arnott, a Scottish-born and trained surgeon, that “both the structural arrangements and the condition of the population in Glasgow was the worst of any we had seen in any part of Great Britain.”11 For his part, Engels quoted from an 1843 article in The Artizan, a newly founded monthly magazine:

The population in 1840 was estimated at 282,000, of whom about 78 percent belong to the working classes, 50,000 being Irish. Glasgow has its fine, airy, healthy quarters, that may vie with those of London and all wealthy cities; but it has others which, in abject wretchedness, exceed the lowest purlieus of St. Giles’ or Whitechapel . . . endless labyrinths of narrow lanes or wynds, into which almost at every step debouche courts or closes formed by old, ill-ventilated, towering houses crumbling to decay, destitute of water and crowded with inhabitants, comprising three or four families (perhaps twenty persons) on each flat, and sometimes each flat let out in lodgings that confine — we dare not say accommodate — from fifteen to twenty persons in a single room. These districts . . . may be considered as the fruitful source of those pestilential fevers which thence spread their destructive ravages over the whole of Glasgow.12

Finally, here is Jelinger Symons, an Assistant Commissioner on an official enquiry into the condition of handloom weavers set up in 1838:

I have seen human degradation in some of its worst phases, both in England and abroad, but I can advisedly say that I did not believe until I visited the wynds of Glasgow, that so large an amount of filth, crime, misery, and disease existed on one spot in any civilized country. [. . .] In the lower lodging-houses ten, twelve and sometimes twenty persons of both sexes and all ages sleep promiscuously on the floor in different degrees of nakedness. These places are, generally as regards dirt, damp and decay, such as no person of common humanity to animals would stable his horse in.13

By 1856, when Nathaniel Hawthorne, then U.S. Consul in Liverpool, visited the city, he commented on the “wide and regular” streets, the statuary in George Square, and the “handsome houses and public edifices of a dark grey stone” in the newer sections, while on a second visit in the following year he declared himself “inclined to think the newer portion of Glasgow [. . .] the stateliest of cities. The Exchange and other public buildings, and the shops in Buchanan Street are very magnificent; the latter especially excelling those of London.” But when he went into the old city to view the University, he was appalled. It was “in a dense part of the town, and a very old and shabby part, too,” he noted in his diary for May 10th, 1856. “I think the poorer classes of Glasgow excel even those in Liverpool in the bad eminence of filth, uncombed and unwashed children, drunkenness, disorderly deportment, evil smell, and all that makes city poverty disgusting.” On a second visit a year later, his impression had not changed: “The Trongate and the Salt-Market [. . .] were formerly the principal business streets, and, together with High Street, the abode of the rich merchants and other great people of the town. High Street, and, still more, the Salt-Market now swarm with the lower orders to a degree which I have never witnessed elsewhere; so that it is difficult to make one’s way among the sullen and unclean crowd, and not at all pleasant to breathe in the noisomeness of the atmosphere. The children seem to have been unwashed from birth.”14

Inevitably, disease was rampant, epidemics frequent, and crime endemic. There were outbreaks of typhus in 1818, 1832, 1837, 1847, and 1851-52; cholera epidemics in 1832, 1848-49, and 1853-54, the last two claiming almost 8,000 lives.15 Though some of the better-off citizens were doubtless troubled in their Christian conscience by the inhuman conditions many of their fellow-creatures lived in, few ventured into the noisome and dangerous parts of their city.16 However, a detailed account of the hunger, drunkenness, promiscuity, prostitution, violence, and crime in the slums was readily available in a popular book put out by a Glasgow publisher in 1858, a couple of years after Annan opened his photographic business in the city. Midnight Scenes and Social Photographs, Being Sketches of Life in the Streets, Wynds and Dens of the City was divided into seven sections, each describing a night in Glasgow’s slums, from Sunday, supposedly the Lord’s day, through the following Saturday. The author apologized in his preface for the gruesome picture his book presented of “the condition of the poor, and the classes generally inhabiting the lower depths of society,” but insisted on its honest and unembellished realism.17 The claim to realism was underlined not only by the use of the common Glasgow dialect among the characters encountered or interviewed by the narrator but, above all, by the photographic metaphor in the title, photographs at the time being popularly considered impartial and objective copies of reality with no input from the photographer other than technical know-how. The metaphorical function of the term “social photographs” is highlighted by the fact that there are no photographs in the book; the only illustration, a frontispiece engraving by the great caricaturist George Cruikshank, depicts a photographer taking pictures of scenes and situations described in the text. (Figs. 26- 27)

Alarmed by the threats posed by the slums to all the city’s inhabitants, the generally progressive city fathers moved to remedy the situation. The Loch Katrine Water Works project was a significant part of their improvement plan. Then, in 1862, the Glasgow Police Act allowed the municipality to regulate small dwelling places (under 3,000 cubic feet), assess the maximum number of inhabitants permitted in each (on the basis of 300 cubic feet per adult and 150 cubic feet per child), “ticket” the dwelling accordingly with a tinplate disc screwed to the door, and have the sanitary police carry out inspections during the night to ensure that the “ticketed” maximum had not been overstepped.18 Apparently this measure was not effective, for it was decided only three years later to proceed to a complete demolition of the tenements as the only remedy.

In 1865 Provost John Blackie (a partner with his father in the notable Glasgow publishing firm of Blackie & Son) and the forward-looking City Architect, John Carrick, drew up the City of Glasgow Improvements Bill, the purpose of which was to authorize the Town Council to buy up and tear down properties in a designated area. The bill was passed by Parliament the following year, making Glasgow “the first municipality to take such action on a large scale.” “Indeed,” one scholar writes, “the improvements scheme . . . was by far the largest and most comprehensive single undertaking of this kind in the nineteenth century” (604). As the area affected was also the oldest part of the city, the City Improvements Trust resolved that, before demolition, photographs should be made of the streets and buildings to serve as a record of Old Glasgow. Annan was commissioned to carry out this assignment, and he began the work in 1868. When demolition started in 1871, he had taken more than thirty photographs.

Issues raised by The Old Closes and Streets

Such, then, were the conditions that led to the commissioning of The Old Closes and Streets. Despite the seemingly straightforward object of the commission, however, these best-known of all Annan’s photographic images have become a topic of lively discussion and debate. Perhaps the first comprehensive collection of photographs ever made of slum properties, are they an early example of “social documentary” photography — “the first major achievement of socially critical photography,” as a modern German scholar has claimed?20 Did they appeal to the viewer’s moral conscience in order to bring about an improvement in the slum-dwellers’ lot? Or should they be viewed rather in the context of the esthetic of the “picturesque,” a mid-nineteenth-century anticipation, according to many scholars, of the pictorialism of Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen at the end of the century and in the first decades of the twentieth century? What is the role of the human figures in many of the photographs? Are they meant to be objects of compassion, a focus of interest in themselves, or are they simply “staffage,” providing a sense of scale as in landscape painting and photography?

The problem of interpreting the photographs is compounded by two factors. First, Annan himself left no commentary on them. In the volumes on the country houses, the Old College of Glasgow, and the Loch Katrine Water Works, the texts are by others. The photographs in the first two albums of The Old Closes and Streets (1871 and 1878) are unaccompanied by any text at all, other than simple identifying captions. The 1878 album was to have contained “an introductory and descriptive letterpress”; but even if the planned text had been included, it would have been written by Carrick, not Annan. An edition of the photographs published after Annan’s death by his son, James Craig Annan, did contain an introductory text by the local antiquarian and artist William Young, but it dealt mostly with Glasgow history and had almost nothing to say about the photographs. Whereas Jacob Riis’s photographs of the slums of New York in How the Other Half Lives (1890) — sometimes held to have been anticipated by those of Annan — were used to illustrate an extensive text in which the photographer-journalist himself exposed and denounced the squalid, inhuman conditions of life among the poor of New York City, Annan offered no clue as to his intentions or his understanding of his work. Unlike those photographers who use text or extended captions to “‘fix’ the image, refusing it the right to vacillate between past and present, ideal and real,” in the words of a scholar of our own time, Annan’s silence, whether deliberate or fortuitous, places the burden of interpretation entirely on the viewer.21

A second difficulty in interpreting the photographs in The Old Closes and Streets is presented by the different techniques employed to produce them over the years and the different publics for which they were intended. Though at least some of the prints were probably first issued singly (Glasgow’s Mitchell Library has several), a first folio album, bound in leather, was put together in 1871. This album, of which it seems only four or five copies were produced — one of them being now in Princeton University’s Graphic Arts Collection — and which has neither title page nor date, contained thirty-one albumen prints.22 It was followed in 1878 by a second album, produced in response to a request from some members of the Improvements Trust that “a copy, in the form of an album, of the series of photographs taken some time ago of the more interesting portions of the City, since, to a great extent, demolished by the operations of the Improvement Scheme, should be furnished to each member of the Trust.” This album, brought out in an edition of probably only sixty copies, bound in heavy crushed green morocco, included nine additional photographs that Annan himself had taken. Instead of the albumen prints of the first album, however, Annan made use of the carbon process invented by the chemist and physicist Sir Joseph Wilson Swan, the Scottish rights to which he had presciently purchased in 1866. Finally, in 1900, James Craig Annan brought out a larger photogravure edition with additional photographs by the Annan firm — but not by Thomas Annan himself — in still very limited editions of 100 copies published by the T. & R. Annan Company and 100 or 150 copies published by James MacLehose, the publisher to the University of Glasgow.23

Each of these print types — albumen, carbon, photogravure — has its own characteristics.24 To what degree do the changes resulting from the different processes both reflect and provoke varying expectations and responses on the part of viewers? For example, the “phantoms” or “blurred ghosts” caused by persons or objects that moved during the relatively long exposure time were removed from the photogravure edition of 1900.25 Clouds were added to the carbon prints, which in general are sharper than the albumen prints and, correspondingly, lack the softer tonal qualities of the latter. The order of the plates also varies from one edition to another. Does that have an effect on the viewer’s reading of the series? How does history itself — the completely changed contexts in which the images are encountered by readers of James Craig Annan’s publication of 1900 or of the Dover Books re-edition of it in 1977, or by twenty-first-century viewers of either — affect the way the images are experienced? As Ian Spring has pointed out, they are perceived quite differently in the shrunken, finance-, culture-, and tourism-oriented, post-industrial Glasgow of the twenty-first century than they were in Annan’s nineteenth-century “Second City of the Empire”: “One generation’s misery incarnate becomes another’s consumable style. Today, shop windows are stocked with Annan prints framed for domestic consumption and countless city centre pubs and restaurants mount Glasgow’s old streets and closes on their walls.”26

The remainder of this essay will be devoted to a closer consideration of two key issues raised by the scholarly discussion of The Old Closes and Streets. First, should these striking photographs be seen as predominantly “documentary” or as predominantly “picturesque”? And second, is documentary photography, as has been alleged, ultimately voyeuristic and exploitative, an act of aggression on its “subjects”?

First, “social documentary” or “picturesque”? Several critics have pointed out that the decision to demolish the old closes and streets had been taken before Annan moved in with his camera and that his assignment was simply to create a record of a significant piece of the city’s past that was about to be destroyed. It is thus unlikely that he “used his camera as a social weapon,” photographing the old closes and streets in order to draw attention to urban blight and promote action to correct it.27 In this respect, therefore, his work should not, it is claimed, be seen as expressive of the same concerns that animated Jacob Riis.28

Should Annan’s work then be seen as closer in spirit and intent, if more modest in scale, to that of certain French contemporaries, such as the photographers of the Missions héliographiques (Baldus, Bayard, Le Gray, Le Secq, Mistral), who had been charged by the Commission des monuments historiques with making a photographic record of all the country’s historic monuments, with special attention to those that were decayed or threatened with demolition; or, closer still, to the work of Charles Marville, who, as official photographer of the city of Paris, had been commissioned in 1862 by the city’s Service des Travaux historiques to record not only the great sites of the city and the grandiose achievements of Baron Haussmann, but also old streets and buildings slated for demolition?29 (Figs. 28-29) This connection is all the more plausible as Provost Blackie and City Architect Carrick were enthusiastic admirers of the redesign of Paris and had led a civic delegation from Glasgow to the French capital in June 1866, the very year in which the City Improvements Act was passed.30 As Susan Sontag noted in her seminal work On Photography (1973), referring in turn to Walter Benjamin’s “Kleine Geschichte der Photographie” (1931), “from the start, photographers not only set themselves the task of recording a disappearing world but were so employed by those hastening its disappearance” (1).

The goal of recording and documenting the architectural heritage, or simply old buildings that had fallen into decay or were about to be torn down, was almost inevitably accompanied by a feeling for the “picturesque,” inasmuch as the picturesque, from the outset, was associated with the old, the decaying, and the neglected or unappreciated. The beautiful, according to one writer at the end of the eighteenth century, depends on “ideas of youth and freshness,” while the picturesque depends on “those of age, and even decay.”32 Thus Archibald Burns, a friend of Annan’s and a successful photographer of old streets and buildings in Edinburgh, entitled his 1868 volume of photographs of the city Picturesque “Bits” from Old Edinburgh.33 (Fig. 30) As a modern scholar has put it, “the picturesque became generalized to that which is multifarious, irregular, unevenly lit, worn, and strange. Everything that appeared smooth, bright, symmetrical, new, whole, and strong, on the other hand, was placed in the categories of the beautiful or the sublime.” Paradoxically, according to the same scholar, this elevation of the picturesque was “based on an over-functionalization of the esthetic.” As it is “more demanding to value something worn and decayed than to like [. . .] what is acknowledged as beautiful, [ . . .] the picturesque provides a test of whether the spectator is always able to assume the perspective of ‘disinterested pleasure’ that Kant designated as a precondition of the esthetic attitude.” 34

The vogue of the “picturesque” thus reinforced the efforts of certain photographers to win respect for photography as an art, and not merely a utilitarian instrument for accurately recording reality — and for themselves as artists more alert than many academically trained painters to objects of unsuspected beauty and suggestiveness, rather than simply skilled technicians.35 As suggested earlier, supporters of calotype, as opposed to the more precise and detailed daguerreotype, had used the argument that Talbot’s process left more room than Daguerre’s for choice and decision making on the part of the photographer. In The Pencil of Nature (1844) Talbot associated his own work with that of the painters of the Dutch school, concerning whom he wrote, “the painter’s eye will often be arrested where ordinary people see nothing remarkable. A casual gleam of sunshine or a shadow thrown across his path, a time-withered oak, or a moss-covered stone may awaken a train of thoughts and feeling, and picturesque imaginings.”

Figures 31 & 32. Two works by Fox Talbot. Left: Open Door. Right: The Haystack.

Many of his own photographs, such as The Open Door and The Haystack,” exemplify this approach.36 (Figs. 32-32) In 1860, Thomas Sutton, the editor of Photographic Notes, the journal of the Photographic Society of Scotland and the Manchester Photographic Society, was more specific: “Although photography is certainly a mechanical means of representing nature, yet, when we compare a really fine photograph with an ordinary mechanical view, we are compelled to admit that it exhibits mind, and appreciation of the beautiful and skill of selection and treatment of the subject on the part of the photographer, to a degree that constitute him an artist in a high sense of the word.”37 The portrait painter Sir William Newton, who also happened to be a vice-president of the Royal Photographic Society in the 1850s, even urged photographers to seek artistic effects rather than a mere copy of nature. “The whole subject might be a little out of focus,” he suggested, “thereby giving a greater breadth of effect, and consequently more suggestive of the true character of Nature.”38

In France, in an 1851 article in La Lumière, the earliest of all photographic journals, Francis Wey explained that, unlike the daguerrotype, the calotype “works with masses, disdaining detail as a gifted master painter does . . . and choosing to emphasize formal qualities in one place and tonal qualities in another.” That is why “the taste of the individual photographer can be discerned sufficiently clearly in his work for the experienced amateur, on seeing a photograph produced by the paper process, to be able to identify the photographer that made it.”39 In short, the photograph can be manipulated, and therein lies its claim to be art.

Thomas Annan did not often express himself on the question whether photography is an art (though his now better-known son James Craig Annan did and asserted unequivocally that it is40). Still, in at least one case — a view of the Palace of Linlithgow — there is material evidence that he first sketched the scene he wanted to photograph and made notes to himself about lighting conditions and the best times of day for camera work.41 From a technical point of view, photographing in the dark closes of Glasgow must have required close attention to light conditions at different times of day and, in view of the long exposure times required, to controlling the movement of people. The pictures were thus necessarily composed with thought and care.

Figures 33-35: Left: Closes, Nos. 97 and 103 Saltmarket. Middle: Close, No. 93 High Street. Right: Close, No. 75 High Street.

Although it was Annan’s brief solely to depict the old closes and streets, many commentators find it striking that, with a few exceptions, such as Closes, Nos. 97 and 103 Saltmarket (Fig. 33), the photographs do not convey a deeply disturbing sense of the extreme squalor and degradation denounced in the literature on Glasgow’s slums.42 The alleys are dark and run down, to be sure, but not especially dirty. On the contrary, there are few signs of refuse, and the lines of washing hung out over them in many of the pictures not only suggest a concern with cleanliness on the part of the inhabitants but also provide a formally effective horizontal complement to the high, somber, and close-packed verticals of the walls. Even if an occasional silvery rivulet running down a cobbled alleyway was the effluent deplored by sanitary inspectors rather than simply rainwater, it also functions to enliven the scene and guide the eye. (Figs. 34-36).

Figures 36-38: Left: Old Vennel off High Street. Middle: Close, No. 80 High Street. Right: Close, No. 29 Gallowgate.

Similarly, isolated figures in some of the photographs appear, with a few exceptions, fairly clean and decently clothed — albeit the children are usually barefoot — and bear little resemblance to the wretched creatures described in the written reports. Often they seem strategically placed to draw the eye along in the direction desired by the photographer. (Figs. 37-38) In other cases, they are grouped or framed in such a way as to be part of the formal design of the photograph. (Figs. 39-40)

Figures 39-41: Left: Close, No. 28 Saltmarket. Middle: Close, No. 37 High Street. Right: Close, No. 118 High Street.

In the words of the scholar who wrote the introduction to the 1977 Dover Press re-edition of The Old Closes and Streets, “Annan’s approach was not what we would call straight.” In the 1878 carbon prints “he added clouds, which brighten the skies over Glasgow’s slums, and he whitened the wash on the line. He did this for pictorial effect, for nice balance.”43 Among Annan’s own contemporaries, the Rev. A.G. Forbes, author of the texts accompanying Photographs of Glasgow (1868) -- refers to him repeatedly as “our artist,”44 while a reviewer of a Photographic Society show in London described Annan’s landscapes as of such “high artistic merit” that their creator “must rank amongst our first class artists.” As early as 1864, in a letter to the Photographic Society of Scotland acknowledging the award of the Society’s silver medal, he himself professed that “my constant aim is to make my Photographs like Pictures and I am happy to think that my efforts are not altogether unsuccessful.” Two decades later, near end of his life, in May 1884, he gave a lecture at a meeting of the Photographic Society in Edinburgh on the topic “Art in Photo Landscapes.”45 It is not implausible, in short, to argue that formal design appears to have been a concern of Annan’s.

The formal, esthetic impact of Annan’s photographs of the old closes and streets has aroused puzzlement and even discomfort in some of the best-informed and most experienced modern students of his work. Sara Stevenson, for instance, qualifies her discussion of these “undeniably beautiful” photographs with a suspicion: “Seeing beauty and poetry in photographs of slums makes us rightly uneasy and doubtful about the photographer — if the photographs are beautiful can he have been concerned about the squalor?”46 Ray McKenzie, the author of several illuminating essays on Annan, acknowledges that it is “impossible to look at a photograph such as “Close, No. 80 High Street” [Fig. 37] without an uncomfortable sense of the ambiguity of our own position as contemporary observers; we are simultaneously appalled by what it tells us about a human situation and thrilled by its uniquely seductive qualities as a photographic print.”47 Margaret Harker concludes that “the strange and lasting fascination of these photographs” is due to the “curious combination between the picturesque and the sordid in Annan’s interpretation of the Glasgow slums.”48

Figure 41. Close, No. 46 Saltmarket

In fact, whatever concern Annan may have had with form did not lead him to avoid representing the inhabitants of the old closes altogether, as is often the case with the street scenes of contemporaries like Charles Marville in Paris and Archibald Burns in Edinburgh (and as he would have been justified in doing by the very terms of his commission, which, it will be recalled, was simply to make a record of the buildings). In other words, the picturesque does not trump the human interest aspect of Annan’s photographs. Sometimes the slum dwellers do seem to be little more than of a piece with and virtually inseparable from the texture of the stone walls they are pressed against or enclosed by. But sometimes, as especially in the images of the closes at 28 Saltmarket, 46 Saltmarket, and 118 High Street (Figs. 40-42), they have a simple dignity that is rarely evoked in the written reports of missionaries, reformers, and inspectors and are clearly themselves the focus of the photographer’s (and the viewer’s) attention. The primary intent of Annan’s photographs may well not have been that of a social reformer like Riis.49

Nor, in contrast to the engravings based on daguerreotypes by Richard Beard in Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1851) or the photographs by fellow Scot John Thomson in his Street Life in London (1878), does Annan exploit and update the traditional “Cries of London” genre — stereotypes of street people or “nomades,” as Thomson describes them, such as the costermonger, the pie-man, the flower-seller, the sweep, the shoe-black, the rat-catcher, the “Jew old-clothes man.”50

Figure 4. The Temperance Sweep by John Thomson. 1878.

First and foremost, it seems to me, Annan’s photographs ask us as viewers to respect the people in them, to recognize them not as “the poor,” or “street people,” or “arabs” — the term by which homeless and uprooted denizens of city slums were often referred to, as though to emphasize that they are virtually of a different “race” from “us” — but simply as human beings.51 Annan’s people, both singly and in groups, need not be viewed as “other” (to be pitied or assisted or feared) as in some “social documentary” photographs of the time. In the group portraits especially, the figures represented seem to assert their humanity, overwhelmed, hemmed in, and rendered fragile as it is by the somber and oppressive mass of their dark, stony environment.52 Given the unavoidably long exposure times required, Annan clearly had to win the cooperation of his human subjects and their willingness to remain absolutely still for several minutes. That he apparently did so would suggest that, instead of regarding him with suspicion, as they often looked on advocates of church attendance and abstention from alcoholic drinks and similar well-meaning but interfering outsiders, the inhabitants of the closes may have seen him as a friendly figure and been pleased or flattered by his non-moralizing attention to them. It may even be that some of them — like the centrally positioned, self-assured male figures, especially the young boy with arms akimbo, looking directly, almost defiantly, at the camera in “Close no. 46 Saltmarket” (Fig. 42) — took advantage of the opportunity provided by the photographer to assert themselves and challenge the viewer to acknowledge them, instead of playing only a passive role as the photographer’s “subjects,” in the full sense of that word. It may be, in other words, that there was a reciprocal relationship between the photographer and his “subjects,” that they had their motives in posing for him just as he had his reasons for having them pose.

Nevertheless — and this is the second of the two issues I would like to explore briefly — a major criticism remains to be considered, one that goes to the heart of any photography that can be construed as having a documentary intent. Hinted at earlier in Ian Spring’s reference to the vogue of Annan’s photographs of the old closes in twenty-first-century, post-industrial Glasgow, it is that raised by Susan Sontag in her essay on photography. “There is an aggression implicit in every use of the camera,” Sontag asserts. “To photograph people is to violate them, by seeing them as they never see themselves, by having knowledge of them that they can never have; it turns people into objects that can be symbolically possessed.” The viewer of documentary photographs easily becomes a voyeur, engaged by spectacle and indifferent to reality: “Aesthetic distance seems built into the very experience of looking at photographs, if not right away, then certainly with the passage of time.”53

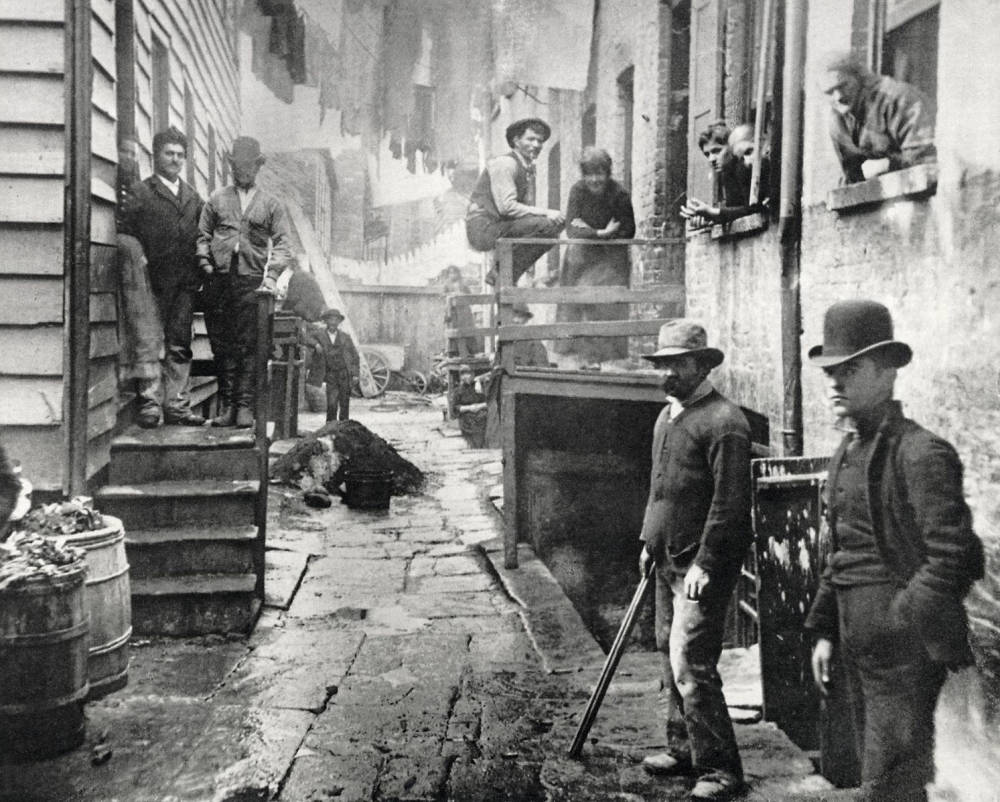

Among many examples of “documentary” photographs that have ceased to function as social criticism and are now almost exclusively regarded as art, one could cite the photographs of exploitative child labor by Lewis Hine in the early years of the twentieth century (Fig. 43), those of the slums of New York by which Jacob Riis sought to arouse the conscience of his readers (Figs. 44-45), and the work of the Depression-era photographers of the 1930s.

Figures 44 & 45. Two works by Jacob Riis. Left: Ragpickers Row. Right: Bandits’ Roost.

An earlier and more disturbing example of the “voyeuristic” character of photography is that offered by Captain Willoughby Wallace Hooper’s photographs of victims of the 1876-1879 Madras famine, which were “sold commercially” and “circulated in private photograph collections, commercially produced albums, and as postcards into the early twentieth century.” It is at the very least uncertain whether they were ever intended to provoke action in favor of the victims.54 (Fig. 46.) Indeed, as Guillaume Apollinaire in his short story “Un beau film” (1901) suggests, the desire to photograph “real” scenes of extreme human violence or suffering may lead the artist wielding a camera to provoke such scenes for the purpose of recording them. In Apollinaire’s story, the filmmaker takes care to assure the public that the murder he set up and then recorded with his camera did in fact take place and was not simply acted. The public responds enthusiastically to this assurance of realism, and the film is a huge financial success.55

Art historian John Tagg sees “the insatiable appropriations of the camera” as one of the ways in which a power relationship is manifested and maintained. The proper question to ask, he argues, is “Why were photographs of working-class subjects, working-class trades, working-class housing, and working-class recreations made in the nineteenth century? By whom? Under what conditions? For what purposes?”56 In Annan’s case, one can answer that his pictures of the old closes and streets were the product of a commission by the municipal authorities of Glasgow, who sought to preserve a record of the dilapidated old buildings in the city center, the demolition of which had been authorized at least as much in the interest of the health of the city as a whole as in the interest of the slum dwellers themselves. As urbanization proceeded apace in the nineteenth century and the traditional fabric and appearance of cities underwent drastic transformations, similar commissions were issued in other places also, notably in Paris. Making, preserving, and collecting records, both written and visual, was in fact a major preoccupation of the century of revolutionary change. While conscientiously executing the task assigned to him, however, Annan also seems to have wanted to give a human face to the often luridly described inhabitants of the condemned tenements.

At the same time, it is certainly the case that Annan’s work — particularly in The Old Closes and Streets — has come to be appreciated by later generations unfamiliar with the concerns of the photographer’s contemporaries not only for its value as a record of a vanished past, but also for itself, for its timeless formal and evocative qualities — in other words, as art.57 There is no evidence that Annan deliberately and consciously used his camera “creatively” to “make art,” as some photographers of his time, such as the popular Oscar Rejlander, did by vying with painters. But as a much-admired photographer of paintings, a good friend of several painters, and an experienced engraver of paintings before he took up photography, he almost inevitably had the painter’s eye for formal qualities when making his photographs.

Toward the end of her essay On Photography Sontag defines photography as a medium like language rather than an art form: “Like language it is a medium in which works of art (among other things) are made. Out of language one can make scientific discourse, bureaucratic memoranda, love letters, grocery lists, and Balzac’s Paris. Out of photography one can make passport pictures, weather photographs, pornographic pictures, X-rays, wedding pictures, and Atget’s Paris” (148). It may be useful to pursue this notion further. A text does not have to be defined solely by its ostensible genre or function: some historical or biographical narratives, some works of political or economic theory or of philosophy are also, by common consent, great works of literature. In a similar fashion photographs may fulfill one or more functions of the medium. Roman Jakobson’s six communication functions of the speech act would seem to apply equally to photography: “referential” (emphasis on the informational content of the message), “aesthetic or poetic” (emphasis on the message itself), “emotive or expressive” (emphasis on the sender and her or his feelings), “conative or vocative” (emphasis on persuading or arousing an active response in the receiver or addressee), “phatic” (emphasis on the channel of communication), and “metalingual” (emphasis on the shared code of communication, “self-referential”).59 And, as in any speech act, while the emphasis may fall -- or be perceived by the listener or reader to fall -- on one or another of these functions, the others are not thereby abolished.

However conscientiously “referential” in providing the record commissioned by the Improvements Trust, Thomas Annan’s photographs do not exclude or eliminate aesthetic, expressive, or conative functions. Different viewers at different times may focus on the information the photographs provide, their formal characteristics, the mood they manifest, or the lesson they urge upon us, and Annan may be judged to have himself emphasized one or another of these functions. The strength of his work may well lie precisely in its ability to stimulate a variety of different readings and responses corresponding to the function that the viewer chooses to perceive as dominant.

“Clyde-built”

When the writer of these lines was growing up in Glasgow in the 1930s and 1940s, “Clyde-built” referred to the ships built in the world-famous yards of Clydebank, Dumbarton, Govan, Linthouse, Scotstoun, Whiteinch, and other districts or suburbs of the city. It denoted the honest, workmanlike, often quite beautiful products of inventive engineers and designers and skilled craftsmen (loftsmen, platers, welders, caulkers). It was a term used with pride throughout the West of Scotland.

It seems not inappropriate to use the term “Clyde-built” to describe Annan’s work. It too is honest, straightforward, technically advanced, often strikingly well designed and stirring, but not artsy. At a time when some photographers were already creating images for purely esthetic effect and others were producing work that could be marketed and sold to the public, Annan worked chiefly on commissions from public agencies and institutions, as well as individuals, industries, and groups. He carried out these commissions imaginatively but always conscientiously. In “the shady commerce between art and truth” that characterizes photography for Sontag, Annan managed to maintain his honesty and integrity. If we are impressed by the formal composition of his photographs, it does not appear that this quality took precedence for him as a photographer over other considerations. As far as one can judge, he remained committed to the idea of photography as an authentic, truthful, and conscientiously made record of “reality” (including works of art created by others) and was not tempted by the artistic ambitions of some of his contemporaries. That commitment was not, however, in the end a handicap. As Sontag observes: “it is now clear that there is no inherent conflict between the mechanical or naïve use of the camera and formal beauty of a very high order, no kind of photograph in which such beauty could not turn out to be present. . . . beauty has been revealed by photographs as existing everywhere” (103).

Last modified 27 December 2025