[This essay originally appeared in The Art Bulletin, 64 (1982), 646-55.]

In addition to depicting himself in oriental costume because it represented his approach to blending realism and imagination, such a manner of self representation emphasizes, even boastfully, his own pioneering efforts in painting naturalistic representations of Bible history.In other words, his self-portrait presents Hunt as the artist who painted The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, The Shadow of Death, and other works that contemporary critics asserted to be revolutionary in their approach to representing biblical history and its embodied spiritual themes.

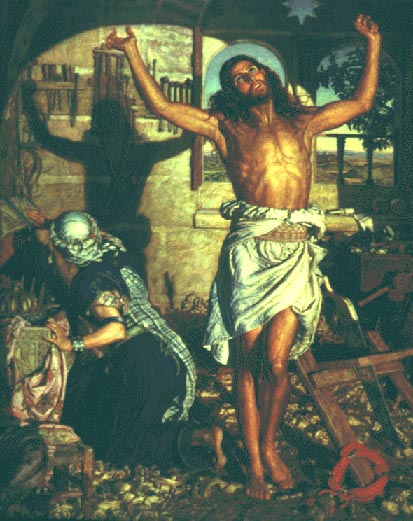

One tenet of naturalism that Holman Hunt always emphasized was that the artist had to render accurately many physical details of a scene, and he did so because he firmly believed that such details generate atmosphere and meaning in a way that an idealized or abstracted setting cannot. The visible embodiment of such belief appears in The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, which came to represent for contemporary English reviewers the epitome of a new school of religious naturalism. The long essays, whether favorable or unfavorable, which the reviewers accorded to this work and the way they continued to refer to it in later years of the century show its crucial importance to Victorian art criticism. The single most obvious feature of this work (and to many, its most shocking) was Hunt's attempt to depict a scriptural scene with absolute accuracy, or as one hostile reviewer phrased it, with "exact material truth." As the sympathetic F. T. Palgrave explained in Fraser's: "By choice and careful study of Oriental figures, dress, and architecture, the outward circumstances have been reproduced, if not with absolute certainty, yet with what is probably by far the nearest approach to fact attained in any Bible picture." There was a great risk, the critic allowed, that "the artist would fall into mere antiquarianism, rest satisfied with splendid surface, or be crushed beneath the pressure of his own gathered ornaments." l6 But he asserted that by correctly subordinating naturalistic details to a powerfully dramatic conception of the scene, Hunt had triumphed over potential difficulties. The Art Journal, which would not allow that Hunt's naturalistic method succeeded at all, was apparently replying directly to Palgrave when it charged that "our conceptions of a sacred event have been taken to Jerusalem but to be smothered in turbans, shawls, fringes, and phylacteries, and there buried in mere picturesqueness." Palgrave's essay appeared in the May 1860, issue of Fraser's, while the Art Journal review that seems directed at it appeared on June 1, 1860. When reviewing E. J. Poynter's The Return of the Prodigal Son nine years later, the Art Journal returned to this same issue, complaining that audiences

are very likely, by plausible theories and partisan propagandists, brought to believe that neither this promising young painter nor any master, ancient or modern, has any right whatever to deal with the often-painted episode before us, without having previously informed himself of the precise shape, measurement, pattern, and material, if not also the market price of the textile fabrics made up into abbah, the under garments, and the potah, or continuation, if any, worn by the excellent parent of the Gospel narrative, on the particular day of his hopeful son's return.

The reviewer here is attacking not only Hunt (whose key-plate to The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple he effectively parodies) but also such critics as F. T. Palgrave and W. M. Rossetti, who had praised Hunt's approach to religious art. The writer's major objection is that "one may read this and every other great lesson of love and mercy without being informed of such particulars, and still, perhaps, forget to feel that the lessons lose any of their weight." Hunt would probably have agreed with this writer, since Poynter was illustrating a parable, not a historical event, and he would have taken for granted that different principles obtained. Hunt's own similar illustrations to parables are much like that of Poynter. Many contemporaries, of course, were unwilling to distinguish between painting parables and literal events in the Bible, though for Hunt, who so emphasized christological typology, such a difference was crucial. 19

According to received opinion, naturalistic detail was acceptable in minor genre painting but not in more ambitious work. Thus, reviewing genre subjects at the British Institution a few years after Hunt exhibited his Finding, the Art Journal stated: "Realism, which high Art should spurn, is in these small transcripts a condition that can scarcely be dispensed with." Hunt, in contrast, believed that high art, art that could equal that of the ancients, required naturalistic technique. In other words, he believed that to challenge the greatness of the ancients, one had to challenge both their methods and the basic assumptions about reality that lay at the heart of these methods.

Hunt had such a reputation as a naturalist that, as he told W. M. Rossetti, "I shall perhaps surprise you by saying that even in painting to my taste there should be great limitations in naturalism, but none not required by the necessity of disencumbering the spectator's mind of impediments to the recognition of the author's main idea." Where the battle between critics and painter arose, then, was simply a disagreement about where the necessary "limitations of naturalism" are found. For the conservative critics still working within the British Academic tradition, almost any naturalistic detail was distracting, for it supposedly displayed lack of imagination on the part of the artist and cur- tailed the exercise of that faculty on the part of the spectator. For Hunt, on the other hand, such detail added to the imaginative effect, in part because it conveyed phenomenological truth. Not surprisingly, when Hunt came to portray himself as artist, he did so in a manner that emphasized not only his characteristic naturalism and Orientalism but also his claims to have pushed these tendencies heroically further in the service of religious art. Hunt's attitude toward naturalistic detail played a major role in his desire to travel to the Middle East in the first place. In fact, as he explained to William Michael Rossetti in a letter he wrote to his friend from Jerusalem during his first visit, he believed voyaging to such exotic places a logical extension of Pre- Raphaelitism:

I have a notion that painters should go out two by two, like merchants of nature, and bring home precious merchandise in faithful pictures of scenes interesting from historical consideration or from the strangeness of the subject itself.... In Landscape this is an idea which Lear has had some time.... It must be done by every painter and this most religiously, in fact with something like the spirit of the Apostles, fearing nothing, going amongst robbers and in deserts with impunity as men without anything to lose, and everything must be painted, even the pebbles of the foreground from the place itself, unless on trial this prove impossible.

Admitting that "men would have to encounter more dangers and inconveniences than painters with a top light in Newman Street," he nonetheless assured Rossetti that "God would guard them in such a work, and the end of such a life would have some satisfaction. I think this must be the next stage of PRB indoctrination, and it has been this conviction which brought me out here, and which keeps me away in patience until the experiment has been fairly tried." One purpose of such a venture, he explained, was to train the artist further in Pre-Raphaelite modes of perception and representation. A second value would come from the records of man and place brought back to England. Ac- cording to him, "in figure pictures the work is just as practicable" as it is in landscape, "and would be easier and easier every year if one commenced. Think how valuable pictures of the social life of the tribes of men who are in this age undergoing revolutions would be in aftertimes."

In Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaetite Brotherhood, Hunt explained that his expeditions to the Orient derived from his lifelong attempts to see for himself — from the same driving force, in other words, that had prompted the Brotherhood's initial testing of the conventions of representation:

I felt it the true education of an artist to see such things, convinced, as I have ever been, that it is too much the tendency to take Nature at second-hand, to look only for that poetry which men have already interpreted to perfection, and to cater alone for that appreciation which can understand only ac- credited views of beauty. The object of this [first] journey had not been the transferring of any special scene to canvas, but rather to gain a larger idea of the principles of design in creation which should affect all art.

Left: The Shadow of Death. 1869-73. Oil on canvas, 84 5/16 x 66 3/16 inches. Manchester City Art Galleries. Right: The Afterglow. Left: 1851-53. Oil on canvas, arched top, 29 ¼x 21 ⅝ inches, Tate Britain, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In the most general terms, painting in the Middle East permitted the painter to see with new eyes — to learn new things about light, air, and color, as he himself tried to demonstrate in The Scapegoat, The Afterglow in Egypt, and The Shadow of Death. In thus aiding the artist to get closer to nature, a nature that was as yet uncontaminated by convention, such a setting would enable him to see and paint more truthfully. As Hunt explained in his memoirs, his immersion in this alien, more primitive world permitted him — forced him — to confront nature more directly:

When I took my walks abroad, and looked upon what passed before my eyes, whether of woe or weal, so much was entirely primitive, simple, and withal beautiful, that . . . I could have no hesitation in being satisfied with the choice for my field of study. In one step I had found escape from the affectations of civilised life. Nature presented itself in its unsophisticated and simple grace, and life reappeared as in its earliest stages. 25

Furthermore, his experience of Middle Eastern life and landscape would allow him to capture specific facts of Oriental life, such as Hunt attempts in A Street Scene in Cairo: The Lantern Maker's Courtship and his many sketches.

Hunt was here also following the Ruskinian program for a modern religious painting. In the third volume of Modern Painters (1856), Ruskin had urged that "sacred art, so far from being exhausted, has yet to attain the development of its highest branches; and the task, or privilege, yet remains for mankind, to produce an art which shall be at once entirely skillful and entirely sincere. All the histories of the Bible are ... yet waiting to be painted." According to Ruskin, the early stages of Pre- Raphaelitism would provide the foundation for such true sacred art; and Hunt seems to have made it his task to ensure that such would occur.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple. William Holman Hunt. 1854-60. Oil on canvas, 33 ¾ x 55 ½inches.

In The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, he made his first attempt at a sacred naturalism that could appropriately communicate the facts of Scripture to his Victorian contemporaries. In his self-portrait, which emphasizes that Hunt himself has lived — and lived as a native — in the landscapes within which scriptural history had unfolded, the painter applied the same precise style to a portrayal of himself as he had applied to a portrayal of Bible fact; and in doing so he reminded the viewer of his stature as a pioneer, or, as Hunt might have put it, as an art prophet.

- Introduction

- Private Meanings: His Family Program

- Public Meanings (I): Hunt as Oriental Traveler

- The Critical Reception of Hunt's Religious Naturalism

Last modified 15 January 2022