[This essay originally appeared in The Art Bulletin, 64 (1982), 646--55.]

During his first visit to the Middle East, Hunt appears wearing an Arab robe under which one can catch sight of European clothing. Hunt thus appears as a traveler to the Middle East, as a European who has taken on the outer garments of an alien land. [Click on picture for larger image.]

he public meanings of the Self-portrait appear in the fact that the painter represents himself in the roles he had enacted when he traveled to the Middle East — those of adventurer, explorer, ethnographer, and pilgrim. Like so many European travelers, he had a love affair with the Middle East; and despite all the hardships and difficulties he endured while painting in Egypt, Syria, and Palestine, he remained enthralled by these lands which had provided the setting for both sacred history and the Arabian Nights. As he told William Bell Scott in 1860 when he was finishing The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, his work on this painting and several other Oriental subjects might temporarily exhaust what he termed his "oriental mania," but his vocation as a painter would not let him stay in England for long: "I cannot believe that Art should let such beautiful things pass as are in this age passing for good in the East without exertion to chronicle them for the future, and I promise myself to return in spirit to the land of good Haroun Alraschid if I can't get there in body before the present year is out" (signed autograph letter, February 18(?), 1860; London; Troxell Collection, Princeton University). The painter's words well capture the complex attraction that this part of the world had for him. At the same time that he felt the urge to play the historian, anthropologist, and ethnographer and thus record the facts of life in these countries, he also indulged the romantic desire to enter the magic realm of the Thousand and One Nights. Similarly, when writing of Damietta, Hunt also describes it in terms of the Arabian Nights: "In the city there were some buildings and a mosque with marble inlaid work that seemed to belong to the time of Harun al Raschid" (Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, 2 vols., London, 1905, 1, 395). Syria, Egypt, and Palestine were, as he put it, his version of "the land of good Harun Alraschid." Like painters as diverse as Frederick Leighton and Thomas Seddon, he frequently saw the Middle East through the distorting, romanticizing lens of Arabian Nights and its magic world of fantasy. For example, Thomas Seddon, Hunt's companion during this first voyage to the Middle East, described Cairo in similar terms on December 10, 1853: "The story-tellers, and men reading outside the coffee-shops, are very Arabian Nightish" (Memoir and Letters of the Late Thomas Seddon, Artist. By His Brother John P. Seddon, London, 1858, 30).

Hunt's letter of March 12, 1854, which he sent to Dante Gabriel Rossetti from Cairo, describes two contrasting forms of exotic appeal. Writing to his friend in London at eleven o'clock on a Sunday evening, he first describes Cairo in terms of Tennyson's "The Lotus Eaters":

The stillness is varied at long intervals by a crowing cock and more frequently by the chanting of an Arab who seems to be returning from some party of hashish smokers. The tune is more than simple, but the most plaintive monotony recalls to one's mind the full hopeless sense of pleasure of Tennyson's lotus eaters. This is no forced comparison for I was going to write that it seemed to convey a wish that time should stop and leave them at peace to sing and sleep for ever, rather than drive them forward through further toil to a greater rest and active enjoyment, when the poem came into my mind as describing the same feeling.

In contrast, when Hunt describes Cairo the next day, he cites, not the languor, but the energy and movement of Middle Eastern life, and he describes the scene in the city streets as a delightfully exotic kaleidoscope:

I have just returned from a walk round the town.... You see the crowd gliding past composed of Arab, Jew, Copt, Turk, Greek and Frank. Here are others also in plenty, Nubian & Abyssinian with Syrian and Persian. Now the crowd is burst open by a party of eight or ten ladies all in charge of an eunuch. They are all closely veiled and their figures concealed as they ride in their elevated seat on their donkey by a large shroud-like black silk hooded cloak, which in filling with wind becomes distended into a full balloon and not only serves the purpose of concealing beauty but also in disguising it into the utmost extent of coveted unattractiveness. Heaven shows a blue sky tonight such as no northern dreamer could conceive and there are stars of colored lamps hanging between us and these minarets, and mosque domes rising in the pearly [649]moonlight over the city gates in front. Now four Meccah men are stalking ... bedecked with tassels which hang about them like the trappings of a princess' choicest horse; and as they pass by two separate women in white mummy dresses slide by like ghosts, and following these fellah girls and Cairene damsels in blue and then Greeks in smart jackets and starched short petiskirts, Bedawees in striped blankets thrown about them as Caesar would have handled the world, Arnaut soldier in frank undercoats and monk-like overcloaks carrying guns with barrels and locks made to look pretty as silver, and townsmen green turbaned, red turbaned and white turbaned — some white as the smoke of hashish shuffling along in loose slippers pipe in hand. (Huntington MS).

Many years later Hunt again described this scene in Cairo; now, however, his emphasis falls upon the transience of human life: "How swiftly transient ... are the most slowly passing scenes! All the actors of that day have now passed away — the Pasha in his gorgeous carriage, with running footman kurbashing the subservient pedestrians.... Now, fifty years later, their places are taken by new actors, and even the stage itself has been changed, yet how vivid and full of life are the memories I retain in my mind as though they had been interrupted only for a moment" (1, 375).

(Travellers Beyond the Grand Tour, a catalogue of a 1980 exhibition at the Fine Art Society, London, contains both valuable information and color illustrations. Kenneth P. Bendiner's "The Portrayal of the Middle East in British Painting, 1835-1860," a 1979 Columbia University Ph.D. dissertation, provides an excellent study of the general subject covered by its title. See also Eastern Encounters: Orientalist Painters of the Nineteenth Century, exh. cat., Fine Art Society, London, June and July, 1978.)

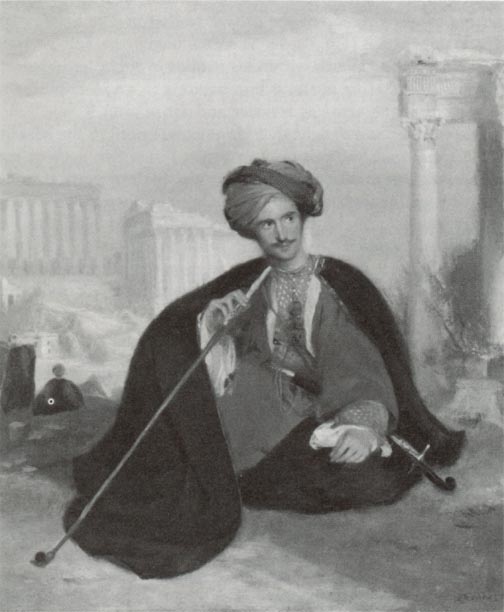

Left: Portrait of George Cummings in Turkish Dress, 1817, by Andrew Geddes (1783-1844). Right: David Roberts Esq. in the Dress He Wore in Palestine, 1840, by Robert Scott Lauder (l803-1869).

Lauder reduces the setting to a few rocks on the left edge of the canvas and fills the background with a mist that obviously owes far more to the North than to the Middle East. This mist serves to create the effect of a never-never land of fantasy. Roberts, sumptuously bedecked in robes, turban, sword, and embellished belt, stands absorbed in contemplation or private fantasy. Lauder's portrait of a painter justly famed for his work in the Middle East provides an image, a memorial, of Roberts' traveling through an alien world. The assumption of foreign dress reveals the English artist perhaps experimenting with a new identity but certainly memorializing a now-finished voyage. Unlike the early photographs of Holman Hunt in Arab robes, Lauder's portrait does not so obviously emphasize a split intention; for although the spectator can tell that Roberts is a Westerner in Eastern clothing, he, unlike Hunt, does not wear a bit of Western clothing to assert that underneath it all he is a European.

Lauder's painting offers a useful contrast to Hunt's Self- portrait because, unlike the work in the Uffizi Gallery, it depicts its artist-subject primarily as a traveler. In his own portrait of himself, however, Hunt chose to combine a costume picture and image of the traveler with one of the artist at work. Wearing what appears to be a silken outer robe, Hunt stands gazing out of the picture space and contemplating the painting upon which he is working. Grasping his palette in his right hand, he rests his left hand and wrist upon a marble-topped table which holds several brushes. Hunt aggressively asserts, in other words, that he is both a traveler to exotic lands and an artist, a practicing artist, too.

Isabella and the Pot of Basil. William Holman Hunt. 1867. Oil on canvas, 23 ⅞ x 15 ¼ inches (60.7 x 38.7 cm.) Signed with monogram and dated lower left. The Delaware Art Museum (ace. no. 47-9) Special Purchase Fund.

Although the Self-portrait's setting is not one of its dominant elements, it does have important bearing upon the overall meaning of the painting. One would therefore like to know precisely what it represents, and several possibilities come to mind. although we know from Hunt's letters that the picture was painted in England, Hunt seems to be depicting himself within one of his foreign studios. The painter, who began the picture in 1867, could be representing himself at work in his Florentine studio. This possibility is suggested since the room's architecture bears some slight resemblance to that in Isabella and the Pot of Basil, 1866-67, which he painted in Florence. He could also be representing himself at work in his Jerusalem studio — a possibility argued for by the apparent likeness of the window or niche on the right side of the canvas to that in The Shadow of Death, 1869-1873. If, as seems likely, the Self-portrait represents Hunt at work within his studios in either Jerusalem or Florence, it therefore portrays him painting in a non-English environment — the artist as traveler and art pilgrim. (In contrast, the pen and ink sketch of himself painting the pyramids and armed with pistol and rifle (this last implement he used to steady his brush) which sketch he sent in a letter of April 26 and 27, 1854 to Thomas Combe, emphasizes Hunt the adventurer — the kind of role he stressed throughout his memoirs and correspondence. The April 1971 catalogue of Hoffman & Freeman, Antiquarian Booksellers, Cambridge, Mass., and Sevenoaks, Kent, reproduces this sketch on its cover.)

The wonder and delight that Hunt experienced in the Middle East encouraged him not only to depict himself in garb of the region but also to return again and again. Sixteen years after he wrote his enthusiastic description of Cairo to Rossetti, the painter attempted to make William Bell Scott understand that he found "true wonder" in traveling through Palestine. "We pass not merely from village to town, and from town to desert, or to an Arab encampment, lying down for the night's rest under the unscreened stars; but we pass from century to century, from Abraham to Cambyses, from Herodotus to Jesus Christ, then to Mohammed and so to the Crusaders. There are, too, such undreamed-of scenes as though they did not belong to this world but rather to the moon" (April 7, 1870; Jerusalem; Autobiographical Notes , ed. William Minto, 2 vols., London, 1892, II, 89). Hunt's concern with the Middle East, his delight in it, stems from a characteristic attempt to combine imagination and fact, for the Middle East was a land of wonder, fantasy, and exotic life — something that had great appeal for him — and at the same time it was a land that forced him as a painter to utilize his talents for detailed representation. The Holy Land, in other words, gave Hunt, as it gave David Roberts, J. F. Lewis, Thomas Seddon, and so many other nineteenth-century artists of all nations, the opportunity to combine the appeals of realism and imagination, physical fact and fantasy.

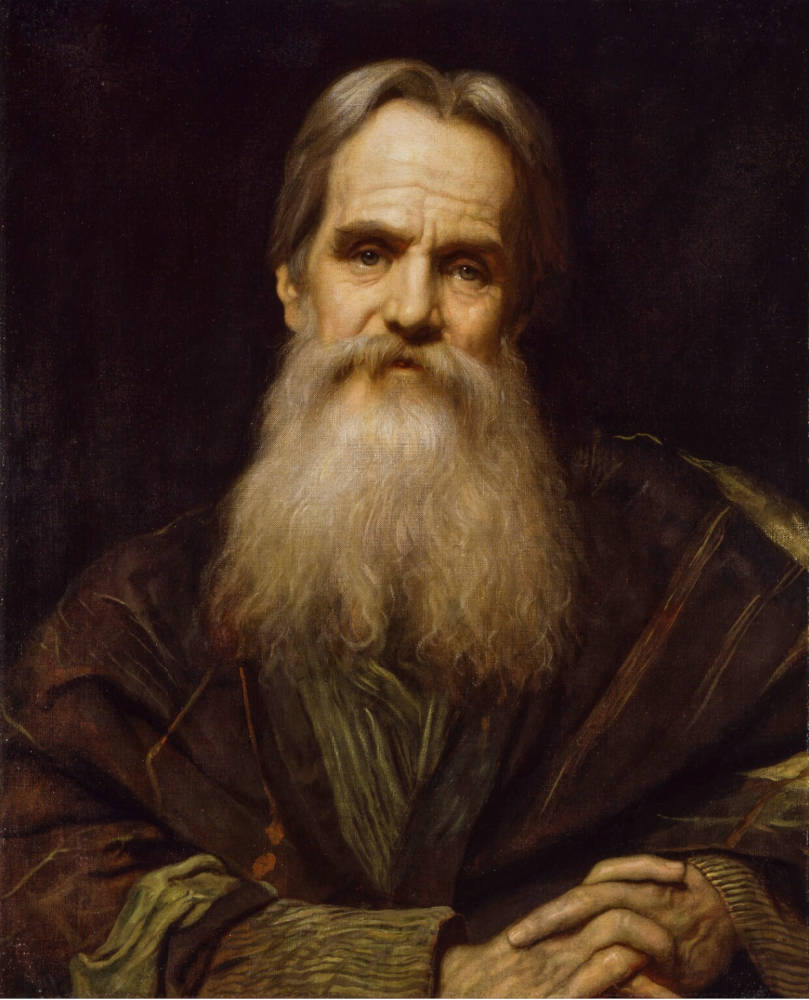

Sir William Blake Richmond’s 1877 and 1900 portraits of Hunt. Note that in the later portrait Richmond, like Hunt in his self portrait, emphasizes middle eastern clothing. Left: 1900. Oil on canvas, 25 ⅞ x 21 ⅜ inches (658 mm x 543 mm). © National Portrait Gallery, London NPG 2803. Given by the sitter's daughter, Gladys Millais Mulock Holman Hunt (Mrs Michael Joseph), 1936. Right: 1877. Oil on canvas, 24 ¼ x 20 ⅛ inches (615 mm x 510 mm). © National Portrait Gallery, London NPG 1901. Bequeathed by Sir William Blake Richmond, 1921

In addition to all these reasons for depicting himself in Oriental costume, such a manner of self-representation emphasizes, even boastfully, his own pioneering efforts in painting naturalistic representations of Bible history. In other words, his self-portrait presents Hunt as the artist who painted The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, 1854-1860 , The Shadow of Death, and other works that contemporary critics asserted to be revolutionary in their approach to representing biblical history and its embodied spiritual themes.

Given the fact that Hunt's works are often thought to exemplify a photographic naturalism devoid of emotional content, one must emphasize that Hunt himself found the landscapes of the Middle East — and the art that depicted them — suffused with powerful emotional experiences. For the mystical, emotional significance of Hunt's personal en- counters with the settings of Bible events, see George P. Landow, "The Religious Significance of Holman Hunt's Realism," in "William Holman Hunt's 'The Shadow of Death,'" Bulletin of the John Rylands Library, 55 (1972): 221-27.

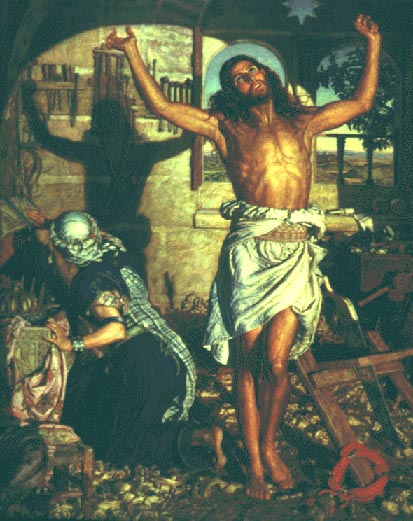

One tenet of naturalism that Holman Hunt always emphasized was that the artist had to render accurately many physical details of a scene, and he did so because he firmly believed that such details generate atmosphere and meaning in a way that an idealized or abstracted setting cannot. The visible embodiment of such belief appears in The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, which came to represent for contemporary English reviewers the epitome of a new school of religious naturalism. The long essays, whether favorable or unfavorable, which the reviewers accorded to this work and the way they continued to refer to it in later years of the century show its crucial importance to Victorian art criticism. The single most obvious feature of this work (and to many, its most shocking) was Hunt's attempt to depict a scriptural scene with absolute accuracy, or as one hostile reviewer phrased it, with "exact material truth" ("Holman Hunt's Picture of 'The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple,'" Illustrated London News, 38, 1860, 411). As the sympathetic F. T. Palgrave explained in Fraser's: "By choice and careful study of Oriental figures, dress, and architecture, the outward circumstances have been reproduced, if not with absolute certainty, yet with what is probably by far the nearest approach to fact attained in any Bible picture." There was a great risk, the critic allowed, that "the artist would fall into mere antiquarianism, rest satisfied with splendid surface, or be crushed beneath the pressure of his own gathered ornaments" ("The 'Finding of Christ in the Temple,' by Mr. Holman Hunt," 61 (1860): 644). But he asserted that by correctly subordinating naturalistic details to a powerfully dramatic conception of the scene, Hunt had triumphed over potential difficulties. The Art Journal, which would not allow that Hunt's naturalistic method succeeded at all, was apparently replying directly to Palgrave when it charged that "our conceptions of a sacred event have been taken to Jerusalem but to be smothered in turbans, shawls, fringes, and phylacteries, and there buried in mere picturesqueness.""The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple," XXII, 1860, 182). Palgrave's essay appeared in the May 1860, issue of Fraser's, while the Art Journal review that seems directed at it appeared on June 1, 1860. When reviewing E. J. Poynter's The Return of the Prodigal Son nine years later, the Art Journal returned to this same issue, complaining that audiences

are very likely, by plausible theories and partisan propagandists, brought to believe that neither this promising young painter nor any master, ancient or modern, has any right whatever to deal with the often-painted episode before us, without having previously informed himself of the precise shape, measurement, pattern, and material, if not also the market price of the textile fabrics made up into abbah, the under garments, and the potah, or continuation, if any, worn by the excellent parent of the Gospel narrative, on the particular day of his hopeful son's return. [54 (1869): 484]

The reviewer here is attacking not only Hunt (whose key-plate to The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple he effectively parodies) but also such critics as F. T. Palgrave and W. M. Rossetti, who had praised Hunt's approach to religious art. The writer's major objection is that "one may read this and every other great lesson of love and mercy without being informed of such particulars, and still, perhaps, forget to feel that the lessons lose any of their weight." Hunt would probably have agreed with this writer, since Poynter was illustrating a parable, not a historical event, and he would have taken for granted that different principles obtained. Hunt's own similar illustrations to parables are much like that of Poynter. Many contemporaries, of course, were unwilling to distinguish between painting parables and literal events in the Bible, though for Hunt, who so emphasized christological typology, such a difference was crucial.

The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple. William Holman Hunt. 1854-60. Oil on canvas, 33 3/4 x 55 1/2 in.

According to received opinion, naturalistic detail was acceptable in minor genre painting but not in more ambitious work. Thus, reviewing genre subjects at the British Institution a few years after Hunt exhibited his Finding, the Art Journal stated: "Realism, which high Art should spurn, is in these small transcripts a condition that can scarcely be dispensed with" (25 [1863]: 48). Hunt, in contrast, believed that high art, art that could equal that of the ancients, required naturalistic technique. In other words, he believed that to challenge the greatness of the ancients, one had to challenge both their methods and the basic assumptions about reality that lay at the heart of these methods.

Hunt had such a reputation as a naturalist that, as he told W. M. Rossetti, "I shall perhaps surprise you by saying that even in painting to my taste there should be great limitations in naturalism, but none not required by the necessity of disencumbering the spectator's mind of impediments to the recognition of the author's main idea" (signed autograph letter; November 20, 1871; Jerusalem; Huntington MS). Where the battle between critics and painter arose, then, was simply a disagreement about where the necessary "limitations of naturalism" are found. For the conservative critics still working within the British Academic tradition, almost any naturalistic detail was distracting, for it supposedly displayed lack of imagination on the part of the artist and cur- tailed the exercise of that faculty on the part of the spectator. For Hunt, on the other hand, such detail added to the imaginative effect, in part because it conveyed phenomenological truth. Not surprisingly, when Hunt came to portray himself as artist, he did so in a manner that emphasized not only his characteristic naturalism and Orientalism but also his claims to have pushed these tendencies heroically further in the service of religious art. Hunt's attitude toward naturalistic detail played a major role in his desire to travel to the Middle East in the first place. In fact, as he explained to William Michael Rossetti in a letter he wrote to his friend from Jerusalem during his first visit, he believed voyaging to such exotic places a logical extension of Pre-Raphaelitism:

I have a notion that painters should go out two by two, like merchants of nature, and bring home precious merchandise in faithful pictures of scenes interesting from historical consideration or from the strangeness of the subject itself.... In Landscape this is an idea which Lear has had some time.... It must be done by every painter and this most religiously, in fact with something like the spirit of the Apostles, fearing nothing, going amongst robbers and in deserts with impunity as men without anything to lose, and everything must be painted, even the pebbles of the foreground from the place it- self, unless on trial this prove impossible.

Admitting that 'men would have to encounter more dangers and inconveniences than painters with a top light in Newman Street," he nonetheless assured Rossetti that "God would guard them in such a work, and the end of such a life would have some satisfaction. I think this must be the next stage of PRB indoctrination, and it has been this conviction which brought me out here, and which keeps me away in patience until the experiment has been fairly tried" (signed autograph letter; August 12, 1855; Jerusalem; Huntington MS). One purpose of such a venture, he explained, was to train the artist further in Pre-Raphaelite modes of perception and representation. A second value would come from the records of man and place brought back to England. According to him, "in figure pictures the work is just as practicable" as it is in landscape, "and would be easier and easier every year if one commenced. Think how valuable pictures of the social life of the tribes of men who are in this age undergoing revolutions would be in aftertimes" (August 12, 1855).

In Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaetite Brotherhood, Hunt explained that his expeditions to the Orient derived from his lifelong attempts to see for himself — from the same driving force, in other words, that had prompted the Brotherhood's initial testing of the conventions of representation:

I felt it the true education of an artist to see such things, convinced, as I have ever been, that it is too much the tendency to take Nature at second-hand, to look only for that poetry which men have already interpreted to perfection, and to cater alone for that appreciation which can understand only ac- credited views of beauty. The object of this [first] journey had not been the transferring of any special scene to canvas, but rather to gain a larger idea of the principles of design in creation which should affect all art. (Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism, II, 75)

Left: The Scapegoat. 1854-1856. Oil on canvas Lady Lever Art Gallery, Port Sunlight (Liverpool). Middle: The Shadow of Death. 1869-73. Oil on canvas, 84 5/16 x 66 3/16 inches. Manchester City Art Galleries. Right: The Afterglow.. Left: 1851-53. Oil on canvas, arched top, 29 ¼x 21 ⅝ inches, Tate Britain, London. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In the most general terms, painting in the Middle East permitted the painter to see with new eyes — to learn new things about light, air, and color, as he himself tried to demonstrate in The Scapegoat, The Afterglow in Egypt , and The Shadow of Death. In thus aiding the artist to get closer to nature, a nature that was as yet uncontaminated by convention, such a setting would enable him to see and paint more truthfully. As Hunt explained in his memoirs, his immersion in this alien, more primitive world permitted him — forced him — to confront nature more directly:

When I took my walks abroad, and looked upon what passed before my eyes, whether of woe or weal, so much was entirely primitive, simple, and withal beautiful, that . . . I could have no hesitation in being satisfied with the choice for my field of study. In one step I had found escape from the affectations of civilised life. Nature presented itself in its unsophisticated and simple grace, and life reappeared as in its earliest stages. (Hunt, Pre-Raphaelitism, I, 376-77)

Furthermore, his experience of Middle Eastern life and landscape would allow him to capture specific facts of Oriental life, such as Hunt attempts in A Street Scene in Cairo: The Lantern Maker's Courtship and his many sketches.

Hunt was here also following the Ruskinian program for a modern religious painting. In the third volume of Modern Painters (1856), Ruskin had urged that "sacred art, so far from being exhausted, has yet to attain the development of its highest branches; and the task, or privilege, yet remains for mankind, to produce an art which shall be at once entirely skillful and entirely sincere. All the histories of the Bible are ... yet waiting to be painted" (Works, ed. E. T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn, 39 vols., London, 1903-1912, 5.86-87). According to Ruskin, the early stages of Pre-Raphaelitism would provide the foundation for such true sacred art; and Hunt seems to have made it his task to ensure that such would occur. In The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, he made his first attempt at a sacred naturalism that could appropriately communicate the facts of Scripture to his Victorian contemporaries. although Hunt completed The Scapegoat (1854-56) long before his representation of the boy Christ in the temple because he had great difficulties in securing native Jewish models, he began the temple picture first. More important, both Hunt and contemporary reviewers considered The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple to be an epoch-making work. In his self-portrait, which emphasizes that Hunt himself has lived — and lived as a native — in the landscapes within which scriptural history had unfolded, the painter applied the same precise style to a portrayal of himself as he had applied to a portrayal of Bible fact; and in doing so he reminded the viewer of his stature as a pioneer, or, as Hunt might have put it, as an art prophet.

Critics immediately perceived the significance of Hunt's challenge to older forms of art in The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple. For example, when reviewing J. R. Herbert's The Sower of Good Seed, the Reader, which took its stand on neutral ground, asked

Who shall venture to pronounce dogmatically in favour either of the ancient or modern interpretation of the facts of Scriptural history? To those who are deeply moved by Da Vinci and Raphael, Herbert's "The Encampment of the Children at the foot of Sinai," at Westminster, is but a congregation of Bedouin Arabs and their Chiefs; and the "Christ in the Temple," by Holman Hunt, reflects but the interior of an Eastern Cafe. To vast numbers of people, these works speak in a new and living voice. ("Exhibition of the Royal Academy," May 13, 1865, 550)

Hunt himself believed that his method of representing the events of the Bible narrative was demanded by the spirit of the age, and within a few years after the painting was initially exhibited an in- creasing number of critics accepted his approach because it had found favor with the Victorian audience. Hunt's works, as the Reader so well put it, "speak in a new and living voice" to many, and that itself was a proof of the method. Not surprisingly, William Michael Rossetti, one of the painter's oldest friends, had words of praise for The Finding of the Saviour in the Temple, and for him it was the embodiment of a new way of painting scriptural narrative. For example, when he reviewed Barwell's Young Saviour Observing the Hypocrites (1865) in Fraser's, he pointed out that the painter's ambitious effort was "a well directed one," because it "proceeds on the 'natural' or 'actualizing' hypothesis of such sacred subjects, like Mr. Holman Hunt's Temple picture" ("The Royal Academy Exhibition," 71, 1865, 752).

Even the Art Journal began to weaken a bit, and when it commented upon paintings of Christ in the Temple by Edward Armitage and W. C. Dobson at the 1866 Royal Academy, it alluded to Hunt; when discussing these painters' rendering of costume, which it took to be a compromise between "the Academic and the naturalistic," it granted that "it is a question, indeed, whether under the prevailing temper of the English mind an ideal or purely imaginative treatment would be tolerated" (28 [1866]: 162). Hunt's success with his public had begun to win toleration, if not approval, from the conservative critics. As his method of scriptural naturalism edged into critical respectability, the reviewers looked around to find historical precedent for it. The Art Journal review of Armitage and Dobson, for example, decided that "Horace Vernet and other French artists led the way" (28 [1866]: 162) — just the opinion to infuriate the intensely nationalistic Hunt! Of course, no one could reasonably claim that he had invented the use of naturalistic details in history painting or high art, nor would Hunt have wished to do so. As he willingly admitted, the precise style that the young painters employed in the early years of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood owed a great deal to Maclise, Mulready, and Dyce, and it was Millais, not Hunt, who led the way in using this style for a scriptural subject. In fact, Hunt was still trying to gain admission to the Royal Academy schools in 1842 when the Illustrated London News explained the ancestry of H. Howard's Aaron Staying the Plague. According to this reviewer, Howard's picture belonged to that department of art,

where pure history is elevated and touches the dramatic, however noble the fact, or however ordinary or simply human; & that section peculiarly English, of which West's "Death of Wolfe" may be considered the foundation — a series of works with the most scrupulous attention, & minute research with regard to all that pertains to date, locality, costume & custom; whilst masses of accumulated detail are wondrously arranged, with due subordination to the main object of the work — the illustration of some event of real history. (Illustrated London News, 1, 1824, 29. I am grateful to Ms. Margaret Kelley, Assistant Curator of the Forbes Magazine Collection, for providing me with a photocopy of this review.)

However much Hunt might have objected to tracing his artistic ancestry back to Benjamin West, an artist whose work he particularly disliked, there can be little doubt that Hunt was but one of the latest and most extreme advocates of adding naturalistic details and genre elements to sacred history. What critics objected to was the degree to which he would carry his researches, a degree that, they claimed, precluded any "due subordination to the main object of the work."

To the end of his career, however, Hunt insisted that although his own love of detail was not necessarily required of a true Pre- Raphaelite style, nonetheless it was what defined his particular Pre-Raphaelite vision of matter and spirit. In his Uffizi Self- portrait, William Holman Hunt presents himself as an artist at work. In particular, he appears as a painter determined to elevate detailed pictorial naturalism above the merely prosaic by using it to depict an exotic subject: this exotic subject is here represented by his Oriental costume, which also serves to portray him as an adventurous pilgrim in the service of art.

- Introduction

- Private Meanings: His Family Program

- Public Meanings (II): Hunt as Religious Naturalist

- The Critical Reception of Hunt's Religious Naturalism

Last modified 15 January 2022