Balaclava by Elizabeth Thompson (Lady Butler), 1846-1933. 1876. Oil on canvas. H 103.4 x W 187.5 cm. Collection and image credit: Manchester Art Gallery, accession number 1898.13, given by Robert Whitehead, 1898. Image downloaded under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives licence (CC BY-NC-ND).[Click on the image to enlarge it.]

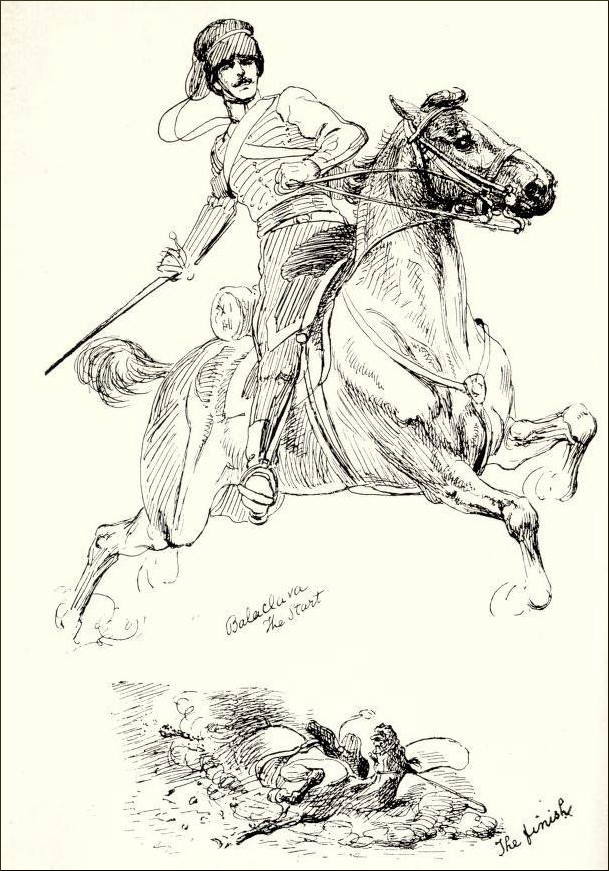

Sketches in preparation for the painting, the top one captioned, "Balaclava The start" and the bottom one, "The finish" (span class="tcbook"> Autobiography, 151).

As usual, the artist made prolonged and detailed preparations for her painting, telling us from her diary entry of The entry for 17 July 1875:

Arranging the composition for my "Balaclava" in the morning, and at 1.30 came my dear hussar [Poor young Inman, who was killed at the fight of Laing's Nek, S. Africa] who has sat on his fiery chestnut for me already, on a fine bay, for my left-hand horse in the new picture. I have been leading such a life amongst the jarring accounts of the Crimean men I have had in my studio to consult. Some contradict each other flatly. When Col. C. saw my rough charcoal sketch on the wall, he said no dress caps were worn in that charge, and coolly rubbed them off, and with a piece of charcoal put mean little forage caps on all the heads (on the wrong side, too !), and contentedly marched out of the door. In comes an old 17th Lancer sergeant, and I tell him what has been done to my cartoon. "Well, miss," says he, all I can tell you is that my dress cap went into the charge and my dress cap came out of it!" On went the dress caps again and up went my spirits, so dashed by Col. C. To my delight this lancer veteran has kept his very uniform — somewhat moth-eaten, but the real original, and he will lend it to me. I can get the splendid headdress of the 17th, the "Death or Glory Boys," of that period at a military tailor's. [138-39]

So horses, uniforms, hats were all researched, studied, verified. No wonder Ruskin found her work as faithful to reality as any Pre-Raphaelite production (308). However, as the sketch shown above left indicates, with its dashing cavalryman representing the start of the battle, and the fallen man and mount representing its ending, it was during this process of immersion in the subject that her theme also became clear. This theme was less in tune with the Victorian mood than with later attitudes, when artists would bring out the suffering of war rather than its possibilities of victory and personal distinction.

Balaclava did not attract as much praise as The Roll Call, Quatre Bras, and the later Scotland for Ever!. William Armstrong felt that "Lady Butler has only been at her best when strong emotion or violent action has had to be rendered" (297). Showing men and horses simply exhausted, some fallen and wounded after the battle, this composition centers on one young survivor, standing in front of them with a set expression, as if to say, "Look, this is what is left of us!" It is very moving, and truthful to what she herself saw as the "pathos and heroism" of war (her own words, quoted in her Times obituary, 17). In this way it is a forerunner of her even more desolate The Remnants of an Army (1879).

Links to Related Material

Bibliography

Armstrong, Walter. "The Henry Tate Collection, V." The Art-Journal, Vol. 55 (1893): 287-301. HathiTrust, from a copy in the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Web. 28 November 2024.

Balaclava. Art UK. Web. 28 November 2024.

Butler, Elizabeth. An Autobiography. London: Constable, 1922. Internet Archive, from a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 28 November 2024.

Ruskin, John. "Academy Notes, 1875." Complete Works, edited by E.T. Cook and Alexander Wedderburn. Vol 14: 263-310. London: George Allen, 1904. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Getty Research Institute. Web. 28 November 2024.

Created 28 November 2024