'Without much presumption it may be affirmed, that . . . there is no species of writing which has such claims on the general attention as that of Biography.' James Field Stanfield, Life of Howard, 1790

Clarkson Stanfield was born in Sunderland, County Durham, on or about 3rd December 1793 above a shop which then stood on the eastern corner of Playhouse Lane, later Drury Lane, where it joined Sunderland High Street.

Behind the shop in the lane itself stood the town's theatre; to the front, the upper windows looked over the High Street and neighbouring buildings to where the masts and spars of Sunderland's busy shipping rose above the river Wear, which flowed to meet the North Sea a bare half mile to the east. If not of prophetic significance it was at least a fitting omen of future events that Stanfield's birth should take place so close to both sea and stage.

Nor was this proximity mere coincidence, for both nautical and dramatic blood ran in his family. His father James Field Stanfield had been born in Dublin in 1749 of untraced though possibly theatrical parentage, and though generally accounted an Irishman was probably descended from English stock. Raised a Catholic, he had trained in France for the priesthood and became an excellent Latin scholar. However, for reasons which are not clear he abandoned the seminary and apparently the Catholic faith as well, and became a merchant seaman. In 1776 he unwisely made a voyage to Africa and the West Indies in the crew of a Liverpool slave-ship. The horrors he witnessed made him a confirmed Abolitionist and in 1788 prompted the publication of his Observations on a Guinea Voyage, a series of letters graphically describing his experiences and addressed to the leading anti-slavery lobbyist, the Reverend Thomas Clarkson.

By this time his profession had again changed to that of provincial actor, he appeared variously from about 1782 at Bath, Bristol, Cheltenham, Lichfield, Manchester and in 1786 on the well-known York circuit. In October 1785 he had married Mary Hoad, an actress, in her home town of Cheltenham and in 1789, when they joined the Scarborough-Durham theatre circuit of James Cawdell, it was at Sunderland that James settled his growing family. For James the town had several advantages; it was convenient for all parts of Cawdell's circuit, which inc Sunderland; it had two flourishing Masonic Lodges in one of which, The Phoenix, he became a leading figure; and it boasted a small but congenial circle of literary men to whom his talents were a welcome addition. If these men, James now included, have no greater claim on posterity they at least take credit for founding the town's first Subscription Library in 1795.

In about March 1793 James temporarily gave up acting to try to make a living as a wine and spirit merchant in the Playhouse Lane shop. By this time he already had four children of whom one daughter, Mary, was to become Clarkson's devoted elder sister and an actress on the Edinburgh stage. A son, James George, later became a seaman gunner in East India Company service but was of sadly unsettled ways and finally died in poverty in 1853.

Clarkson Frederick Stanfield1 was the fifth and youngest child from his father's first marriage, being given his distinctive first name (the only one he ever used) in honour of the Abolitionist. Little is known of his childhood but the mis-spelt scrawl of both Stanfield and his sister's youthful letters indicate that their education was probably rather haphazard despite their father's learning. Stanfield however had an early taste for reading no doubt encouraged by his mother, who herself was credited with a book of children's stories, was an artist and taught painting. She died in January 1801 but not before passing on her artistic taste and abilities to her son. To the usual question, 'what are you going to be?', Stanfield is reliably reported to have regularly given the answer 'a parson or a painter'.

If only for financial reasons the former was clearly impossible. James Stanfield's business was not successful and from early 1796 he was regularly back on the stage with Cawdell. In 1799, when Cawdell retired and Stephen Kemble2 took over his circuit, James and an actor partner called Graham established their own small touring company; while Sunderland remained their base they tramped the road for some ten years playing in theatres, barns and at race meetings from Edinburgh to Scarborough. It is likely that Stanfield learned something of scene-painting from his father at this time as well as sometimes appearing in child parts. -

In October 1801 James Stanfield remarried to Maria Kell, a girl much younger than himself and previously his ward, and further additions to the family soon meant fresh plans for its older members. In 1806 Stanfield was apprenticed in Edinburgh to an heraldic painter, whose business largely centred on the decoration of coaches. Unfortunately the painter's wife had an insatiable appetite for gin which she fed by using Stanfield as a go-between in converting items of his master's property into more liquid assets. After two years this became intolerable and Stanfield ran away, persuading his father to let him go to sea in a collier in 1808. By 1812 he was among the crew of the brig Alexander, Captain J. Donkin, working out of North Shields to London and perhaps as far as the North German and Danish coasts.

However, while in London that year the Alexander was taken over as a military transport — an occupation for which the crew appear to have had little taste since they rather precipitately left her. If their intention was to avoid the press-gang they did not succeed for they were taken by the Thames Police and on 31st July 1812 were handed over to the Navy. The circumstances are mildly suspicious, for the Police were not part of the Impress service (though they often supplied it with their catches) and Stanfield, either to cover his tracks or provide room for manoeuvre, falsely told the Navy that his name was 'Roderick Bland'; by this alias he was known for the next four years. On 25th August he was drafted into H.M.S. Namur the port guardship3 at Sheerness, at the junction of the rivers Thames and Medway.

The talents of 'Able Seaman Bland' were quickly spotted. An application from the Captain for someone to paint a toy coach for his children brought him to notice, as apparently did his scenery for some amateur theatricals on board early in 1814. In these the future playwright Douglas Jerrold also participated, having joined the ship as an eleven year old volunteer in December the previous year. In the spring when a new house was being completed ashore for the port admiral a new opportunity arose;

'I was sent on shore', wrote Stanfield to his father, 'to do a painting for the admiral's Ball room, which I did so much for the satisfaction of the Commissioner of the Sheerness Yard that he promised, when finished, not only to get me my discharge from the Service, but gave me a situation in the Dock yard. Encouraged by this I worked day and night at it for three weeks when, to my utter disappointment Commissioner Lob died, and with him all my hopes ... at length by a close application to the painting, my health was so far reduced that I was found of no more use to them therefore was sent to sea.

'"Disguise thyself as though wilt (says Sterne) still slavery, still thou art a bitter draught, and though Thousands in all ages have been made to drink of thee, thou art no less bitter on that account."'4 Yet would I bear with it my dear father if I thought it would give me an opportunity of relieving those wants which I know you sustain, and which I ought before this time to be able to relieve, but all at present appears a Blank ... I do not know what they are going to do with me...'

He was certainly of little further use on the Namur and by mid-November his physical state, probably including a leg injury, was so bad that he was hospitalised and on 9th December discharged from the Navy as unfit for service.

After visiting his family in Scotland he returned to London and in March 1815 was in the crew of the Indiaman Warley when she left the Thames bound for Whampoa in China. While Napoleon's empire crumbled at Waterloo the Warley was making an uneventful voyage, though one which provided Stanfield with plenty of opportunity to sketch. He returned to his family in May the following year with a reputedly impressive portfolio, a hammock full of souvenirs and a pet monkey called Jack.

His career then suddenly and dramatically changed course. For though he had arranged to join the Indiaman Hope bound for Madras in July, the ship did not sail and he was left in dire need of work. Already possessed of theatrical and artistic contacts in London (including the painters W. J. Huggins and Alexander Carse) he gravitated to the sailor quarter in Stepney, and managed to obtain work as a scene-painter in the East London (formerly the Royalty) Theatre, Wellclose Square. This was not effected without difficulty for the scene-painting fraternity practised the 'exclusive' system or closed shop, which debarred those who had not gone through an apprenticeship. Stanfield consequently had to endure some rough treatment, his colleagues forcing him to work apart and 'even refusing him the paltry favour of warming his size-kettle, a most essential thing in Scene-Painting, in their room'.5 From this it is clear that there was some friendly interest acting in his favour in obtaining the job, in which he swiftly made his mark; by the end of 1817 he had his own apprentice, Robert Jones, and was being paid £3 per week as the principal house artist. Supplements to his income came reputedly from occasional sign-painting and from weekend work in almost forgotten country theatres near London, that at Highgate in the summer of 1817 in particular,

Success in the East End dock area - far from the fashionable whirl of Westminster - was hardly the acme of the young Stanfield's ambition. Consequently when the new and elegant Royal Coburg Theatre opened, south of the Thames in Lambeth, in May 1818, Stanfield was glad to be among those of the East London company whom the manager Joseph Glossop engaged for the opening season. It was however not until 1819 that he finally gave up his East London commitments.

Although Stanfield was initially engaged at the Coburg in a third-rate capacity under the scenic director J. T. Serres6 his gifts made a fairly swift impression. 'The scenery of the Coburg ... in the early seasons was beautifully executed', wrote Horace Foote in 1829, 'for it was at this house that the fine taste of Stanfield was first introduced to the public'. Tales also began to circulate concerning both Stanfield's powers of endurance and the speed at which he worked — the latter being a point for which he was to become celebrated. At the end of 1819 Glossop showed his confidence in the young painter by sending him with his stage manager William Barrymore to mount a Christmas season of melodrama and spectacle at Astley's Amphitheatre — the first time that house had been opened for a winter season. The experiment was a considerable success and late in 1820 Stanfield accompanied Barrymore on tour to Edinburgh. Here, while working with the Astley's company at the Pantheon, he had an introduction through his father to the younger David Roberts, then scene-painter at the Theatre Royal. Stanfield was henceforward to be closely associated with Roberts as colleague, friend and rival. Early in 1821 he briefly joined Roberts and his own sister Mary at the Theatre Royal; here as at the Pantheon his scenery had an immediate success and displaced some of Roberts' best efforts, much to the latter's chagrin. At the same time Stanfield did not neglect other interests, gathering Scottish sketches for future use and showing three pictures at the Edinburgh Institution of Fine Arts exhibition in the spring.7 These, according to Roberts, were 'the talk of the town'.

Stanfield returned to London and Astley's before Easter 1821 and in October went back to regular work at the Coburg. In September 1822 he was briefly joined there by Roberts, who had come to London at Barrymore's instigation.

Etty in the Life School by William Holman Hunt. [Not in print version.]

By this time Stanfield was already an established figure in Lambeth's populous theatrical and artistic community. From living in the Stepney area he had moved in 1819 to 14 Pratt Street, Lambeth; in Pratt Street he had become both a friend and neighbour of the Scottish landscape and marine painter John 'Jock' Wilson (1774-1855) whose work as a scenic artist he greatly admired. Wilson was a pupil of Alexander Nasmyth whose artistic advice on 'forming a style' Stanfield had already sought in Edinburgh and whose son, the landscape painter Patrick Nasmyth, was also one of Stanfield's Lambeth friends. Others of this circle, all with dual artistic and theatrical connections, were Thomas Barker the panoramist, J. M. Wright, J. W. Alien, Charles Tomkins, David Roberts and probably the young George Chambers. William Etty then a rising historical and figure painter whom Stanfield also met as a Lambeth neighbour, was to become one of his principal champions at the Academy as well as being some influence in his development of strong religious convictions.

After 1820 there was not a year, save 1839, in which Stanfield did not contribute to the London exhibitions. He made his debut at the Academy in 1820 with A River Scene, said to be a view of the White Mill at Thames Bank, but most of his work up to 1829 was seen at the British Institution, Pall Mall, and the Society of British Artists in Suffolk Street. With Wilson and Patrick Nasmyth he was one of the foundation members of the British Artists in 1823 and one of the strong contingent of landscape and scene-painters who did very well out of its first exhibition the following year. He was deeply involved in the Society, frequently acting in concert with Wilson. Wilson was the Society's President in 1827 and Stanfield, after serving as Vice President the following year, himself became President in 1829 with Roberts as his 'Vice'.

As for his domestic life, Stanfield's family connections remained firmly theatrical. In July 1818, aged twenty-five, he had married a nineteen year old actress Mary Hutchinson, their first child Clarkson William being born the following year. Two years later, in November 1821, Mrs. Stanfield died shortly after the birth of a daughter, Mary. By 1824 Stanfield's father and at least one of his young step-sisters were living with him or near him in Lambeth. For some years too, his step-brother William James (1804-27) had been under his tutelage and was now doing well as a minor theatre scene painter in his own right.

In May 1824 James Stanfield died with the final satisfaction of seeing his son engaged again, to Rebecca Adcock, the gifted younger daughter of old acting friends from the north who were then working at the Surrey Theatre. The marriage took place at the turn of 1824-25, the new Mrs. Stanfield giving up her occasional acting on the birth other son Henry, probably in 1826. A second son, George, followed in 1828. By then the family had moved from Lambeth to become Thames-side neighbours of Etty at 14 Buckingham Street, off the Strand8 — an address far more suitable for Stanfield's now wide theatrical and artistic commitments.

In November 1822 the Coburg Theatre had been thrown into crisis when Glossop, pursued by creditors, had fled the country two steps ahead of a warrant for his arrest. At the same time death deprived Elliston, the 'Great Lessee' of the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, of one of his principal painters during the run-up to the critical Christmas pantomime season. Though he had already engaged Roberts, Elliston had been casting an envious eye at Stanfield's success across the river and promptly obtained both his services and those of Alexander Nasmyth from Edinburgh for the pantomime Gog and Magog. Save in its scenery this was a disaster but the brilliance and speed with which Stanfield and Barrymore revised it into the successful Golden Axe led Elliston to take them both on his permanent staff. Stanfield signed a contract for an initial three years at £8 per week on 14th January 1823.

As Elliston had intended, the addition of Stanfield and Roberts to Drury Lane - helped by astute publicity and the still new medium of gas lighting illuminating their scenery with unprecedented brilliance — led to a new epoch in the scenic reputation of the house. Previously Covent Garden had held the palm, partly due to its greater structural convenience for spectacle but largely because of the presence there of the long established and talented Grieve family of scene-painters.

This situation quickly changed as Elliston pursued a progressively more extravagant policy, in which Stanfield and Roberts were allowed to vie — increasingly acrimoniously — in general scenic reputation. Stanfield quickly got the lead of the senior house painter Marinari and at Christmas 1823 produced the first of a succession of 'moving dioramas'9 which were to become the feature of Christmas pantomimes and on which a great deal of his fame was to rest. In this area his reputation quickly became unassailable. As early as March 1823 The Times, reviewing a Chinese-style spectacular, considered the scenery was 'upon a par with the best things of the kind which have been done at Covent Garden. This production will certainly completely do away with the idea that splendid and effective scenery cannot be got up at Drury Lane'.10

In January 1826 an unidentified reviewer remarked on the wider effects that the increased competition between Drury Lane and Covent Garden was having on the London stage in general; 'it is astonishing' he wrote 'what effect the admirable scenic efforts of Messrs. Grieve at one house and Messrs. Stanfield and Roberts at the other have produced on ... the minor theatres' ' and by March, the Morning Chronicle's measure of praise of young Danson's scenery at the Coburg was simply to pronounce it 'equal to any effort of STANFIELD'.11

By the time Elliston's irregular life-style and over-liberal expenditure ended in the collapse both of his health and, in the summer of 1826, of his management, the scene-room contest between Stanfield and Roberts had led temporarily to an open breach. Rationalising his own disappointment and jealousy at always being granted second rather than first place in the inevitable comparisons, Roberts claimed that Stanfield could never brook a rival and 'although . . . strictly honourable in everything else - will stand on little ceremony in pushing aside any who stand between him and his advancement in art'12 He thus resigned from Drury Lane in April 1826 and went to Covent Garden, coming into even sharper conflict there with the Grieves — and left Stanfield in victorious possession of the Drury Lane scene-room.

Nobody, least of all the Theatre proprietors, now underestimated the importance of retaining Stanfield if the house was to recover its fortunes and in May 1826 the Committee 'presented a handsome silver vase to Mr. Stanfield as a testimonial of... the high sense they entertain of his great exertions in the scenic department of the theatre'13

In December 1825 The Times in a theatre review had predicted that both Stanfield and Roberts would 'become highly eminent as contributors to those institutions which have been established for the encouragement of painting in this country'. Three years later, reviewing his diorama of 'Spithead to Gibraltar', in the Drury Lane pantomime the Queen Bee, the same paper summarized the scenic improvements for which it now considered him responsible:

When our memory glances back a few years and we compare in "the mind's eye", the dingy, filthy scenery which was exhibited here — trees, like inverted mops, of a brick-dust hue — buildings generally at war with perspective — water as opaque as the surrounding rocks, and clouds not a bit more transparent — when we compare these things with what we now see, the alteration strikes us as nearly miraculous. This is mainly owing to Mr. Stanfield. To the effective execution of the duties belonging to the scenic department, he brought every necessary qualification — a knowledge of light and shade which enabled him to give to his scenes great transparency and a ready and judicious taste for composition, whether landscape, architecture or coast, but more especially for the last. . . His present scene is fully equal — in some parts superior - to any thing he has heretofore done . .. The view of Lord Nelson's ship the Victory, is the most gorgeous specimen of naval architectural painting that we ever saw ... The view of Gibraltar, bristling with fortifications is uncommonly fine. It exhibits an extent of space... and a grandeur of elevation which seem to say "I am invulnerable".'14

A few weeks before this particular scenic triumph — itself only the first of the six great Christmas dioramas which were to be the high points of his later theatrical career — Stanfield had succeeded Wilson as President of the Society of British Artists; his year of office saw him well established as a man of two worlds, causing some astonishment by doing so much and so well in both. His theatre fame apart, he had considerable easel patronage, his prize-winning Wreckers off Fort Rouge (British Instituton, 1828) was being engraved as a large plate and he had made inroads in the profitable field of topographical illustration with his first contributions to George Cooke's London and its Vicinity. Reference to the diary of E. W. Cooke, George's son, also shows the extensive circle of engravers and painters in which he was regularly found, either privately or at the growing number of conversazioni of the time15 — the Cookes and the Findens notable among the engravers; Clint, Etty, Simpson and Mulready among the oil painters; J. S. Cotman, J. D. Harding, Samuel Prout and Boys among the watercolourists. He evidently knew Turner from early on (both, for example, being on the Artists' Benevolent Fund Committee in 1829) and Constable, whom he met a little later, took an immediate liking to him.

Handsome, sociable, with a good sense of humour and the ability to charm a company with a sea song or story, Stanfield was widely liked for an unaffected modesty about his own achievements and his straightforward simplicity of character. Though in his private life we know he suffered considerable anxiety manifested in sometimes black temper and growing religious devotion - the worst said about his public personality was Roberts' biased assertion that he had a ruthless professional ambition. To most people, however, he appeared to be 'a man of simple quiet habits, and seemingly absorbed in his art'16 and he himself was conscious how much his 'undemonstrativeness' and capacity to listen and observe recommended him to more brilliant company.17 He was going to require all his advantages of art and character in the struggle for admission to the Royal Academy.

Clarkson Stanfield, R. A. by William Brockedon (1787-1854). 1833.

Much of Stanfield's easel and theatrical work was based on extensive domestic and foreign tours. He appears to have made the first of his many continental visits in 1823, travelling briefly through Holland and Belgium to the Rhine during the summer. The following year he struck out with his friend William Brockedon on the first of the expeditions during which that intrepid tourist compiled his Illustrations of the Passes of the Alps. In 1825 Drury Lane subsidised a tour up the Seine to Paris, to provide material for a panorama in a spectacle based on the coronation of Charles X that year.18 A further trip to the Rhine in 1828 ended in disaster when Stanfield contracted pleurisy at Cassel and spent his entire tour period convalescing at Calais and Boulogne.

In 1829 he was less ambitious, touring Cornwall in September and preparing for a large picture of St. Michael's Mount. When hung at the Academy in 1830 the picture became the subject of acrimony between Stanfield and the Society of British Artists; the large canvas was clearly a bid for Academy recognition and it was against the conventions if not the rules of the Society to make such a move while remaining one of its members. For the immediate past president also to have ignored the Society's own exhibition that year made matters worse and in June Stanfield found it expedient to follow his friend Etty's advice to resign from the Society. At the same time the new king William IV (an experienced seaman if not a great connoisseur) had seen the picture and, much struck with its stormy sea effects, commissioned two works from Stanfield. The first of these was a view of Portsmouth; the second, originally of Plymouth, was changed to The Opening of New London Bridge. This, after some ill-defined carping on Stanfield's lack of qualification as a non-Academician to paint such a prestigious commission, was hung at the Academy in 1832 and was generally well received.

The Opening of London Bridge by William IV, 1 August 1831. Oil on canvas, 71 x 91 cm. Collection: Guildhall Art Gallery, London. Reproduced courtesy of the City of London Corporation.

Whereas in 1830 Stanfield had begun to despair at ever being elected to the Academy and was defeated in the A.R.A. ballot both in that year and in 1831, the Royal favour effectively secured his future. The Academy elected him Associate in November 1832 by a resounding majority (20:6 against H. P. Bone) arid other patrons followed the Royal lead; Lord Lansdowne in particular ordered the first of ten pictures Stanfield was to paint for Bowood between 1833 and 1845 and the Duchess of Sutherland later asked for another five. In 1833 he also began work on a massive picture of the Battle of Trafalgar for the United Service Club as a pair to a Battle of Waterloo by George Jones. The prestigious work, effectively compromising art with a strict historical brief, was exhibited in 1836.

Both the Bowood and Sutherland commissions were largely based on a tour which Stanfield had made up the Rhine and to Venice in the autumn of 1830. From this also resulted the first of his three Picturesque Annuals for Charles Heath - Travelling Sketches in the North of Italy . . . (1832) — as well as the large dioramas of the Alps and Venice and its Adjacent Islands for the Drury Lane Christmas pantomimes of 1830 and 1831 respectively. The latter according to The Times was one of his most artistic, rather than purely spectacular, triumphs being painted 'with a truth and finish which were never bestowed upon scene painting in our times at least, until he applied his talents to the work'.19

The Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly designed by P. J. Robinson. 1811-12. Photograph 1895. The Hall, which was torn down in 1905, was at 170/171 Piccadilly. [Not in print version.]

By the time the Venice diorama appeared — contemporary with the publication of Heath's Annual - and while he was working on London Bridge, Stanfield had been at Drury Lane ten years. During this time he had not only worked in theatre and gallery but had fairly regularly been painting more miscellaneous spectacles for non-theatrical exhibition — panoramas in 1824 and 1828, a 'Poecilorama' for the Egyptian Hall, and an outdoor 'Ruined Abbey' at Vauxhall Gardens in 1826, and several dioramic pictures for 'The British Diorama' at the Royal Bazaar between 1828 and 1830. How long he was going to maintain such a large and diverse output was a serious question.

In terms of the social, literary and moral status that it was granted by 'respectable' opinion, the English stage and its drama were at their lowest ebb during the period centering on Stanfield's career. By contrast the purely visual arts, be they easel painting or non-theatrical panoramic exhibitions (those things, in short, which were fairly safe from giving unpredictable shocks to delicate sensibilities), were granted high favour as aesthetically, educationally and socially improving. It might therefore be expected that there was considerable pressure on Stanfield, so obviously able to succeed outside the theatre, to quit the stage. In fact this does not appear to have been the case, at least so far as a consensus can be defined from the opinions of dramatic critics. For while Stanfield was praised in all areas of his art he excelled in his theatre work, teaching 'pit and gallery to admire landscape art and the boxes to become connoisseurs'20 This praise lavished on his stage work, which 'helped to raise scene-painting up to art'21, was consequently something more than an aesthetic verdict. To some degree it was a moral endorsement of his part in importing the respectability of fine art into the traditionally disreputable theatre.

Looking at Stanfield's easel works, B. R. Haydon and fellow purists at the London exhibitions could sneer that 'Stanfield [is] a scene painter in little'2" but his paying public had a different opinion. 'STANFIELD', wrote one unidentified critic in 1830, is 'an artist who certainly never has been equalled in the [scenic] art to which he lends his great talent, and whose splendid pictures in our recent exhibitions prove a diversity of genius ... rarely centering on one individual'.

Nonetheless Stanfield had hardly been elected A.R.A. before there was a general assumption that he would now give up scenic work, and though this proved baseless, there was a persistent undercurrent that 'for his own good' he ought to abandon it. John Murray, the publisher, exemplified the feeling in February 1834 when he chided Stanfield for being six months behind in his drawings for an edition of Crabbe's poems, largely because of theatrical commitments: 'Your best friends' he wrote 'think that you are injuring your fortune — your art — your high rank and your Health by the fatalism of your Slavery to the Stage'.22 Stanfield, a steady percentage of whose income was now coming from just such publishing commissions as those regularly given to him by Murray, could only agree. Taking Murray at his word he assured him that he would either immediately give up theatre work or enter 'into some other arrangement with the Manager so as to have sufficient command of my time to execute the commissions I have undertaken [;] for to continue the slave I have hitherto been ... is out of all reason'.23

Not the least factor contributing to this decision was the fact that from 1831 Drury Lane's manager, subsequently its lessee, was the infamous and indestructible Alfred Bunn. Bunn in fact controlled both Covent Garden and Drury Lane between 1833 and 1835 and though this monopoly was merely one aspect of his pragmatic - even enlightened and advanced — ideas of theatrical management, the results were notorious. While Covent Garden had some great successes with opera and ballet, 'The Drama' as a whole was effectively given the coup de grace at Drury Lane in favour of spectacular pantomime and animal circuses. Ten years earlier this would all have been grist to Stanfield's mill but by 1834 the steadily increasing theatrical pressure, comprising both his Drury Lane work and some at Covent Garden, was too much. Bunn moreover was at best a shady character whom Stanfield knew of old and with whom he had no personal sympathy.

Consequently, when at Christmas 1834 a dispute arose over the precedence between scenery and horses, in the equestrian spectacle King Arthur and The Knights of the Round Table, Stanfield was prepared to make an issue of it. Overruled by Bunn he resigned from the theatre after exactly twelve years' service. Within six weeks, on 10th February 1835, he was elected a full Royal Academician. Considering the general anti-theatrical prejudices of the time, it is hard to believe that the succession of one event on the other (especially so swiftly) was entirely the product of coincidence. His resolution to keep off the stage was however not long maintained. Though obliged, in 1836, to decline T. N. Talfourd's request to paint a scene in his Ion for their friend Macready, he was soon helping that great tragedian both with advice and painting during his managements of Covent Garden (1837-39) and Drury Lane (1841-43).

While quite separate from his main scenic career, these were important occasions for Stanfield. They not only added a legendary gloss to his reputation, but in the case of Henry V (Covent Garden, 1839) and the opera Acis and Galatea (Drury Lane, 1842) his scenery, patiently devised in collaboration with Macready, materially aided the latter's work in pioneering modern ideas of integrated stage direction and design.

It was probably in 1837, and through Macready, that the forty-two year old Stanfield met the twenty-four year old Charles Dickens, who among his friends of the next thirty years was to be 'the one of all... he most affectionately loved and to the last'.24 The large surviving correspondence from 'Dick' to 'Stanny' proves how fully this feeling was reciprocated. Despite, or more probably because of, the differences in their ages, gifts and temperaments, the novelist found in Stanfield's undemanding company, open simplicity and general good humour, a temporary relief from the problems generated by his own far more complex personality and relationships. The Dickensian charisma and their mutual dramatic interests — even excluding Stanfield's part in the famous Dickens theatricals — are sufficient to explain Stanfield's attraction to the younger man. Once in and of the Dickens circle, he clearly enjoyed the role of imperturbable foil to its more mercurial temperaments; and though the divisions which sometimes occurred between other members certainly upset him, he seems to have preserved an unassailable innocence which defended him from partisan involvement. He could occasionally produce his own social surprises, (as when in 1844 he inveigled Turner, never a man for literary company, to a Dickens dinner at Greenwich) but more generally it was Stanfield who was the audience, others the performers. His portly, middle-aged figure rolls through Dickens' letters trailing a tang of scenepaint and salt water - bluff lieutenant of an Expedition, enthusiastic ally in an amateur theatrical, willing and astonished supplier of top hats from which the brilliant 'Boz' will conjure marvels to startle the company. Dickens' picture of the older Stanfield is certainly attractive but, as with his fiction, the letters also contain an element of caricature which it would be dangerous to take entirely at face value.

Social life apart, much of Stanfield's time in the late 1830s was taken up with book illustration and travel. 1835-36 saw the publication, in parts, of his Coast Scenery, A Series of Views in the British Channel which on its completion was dedicated to the King. In 1836, the year which saw the exhibition of his great Battle of Trafalgar, he also illustrated The Pirate and the Three Cutters for his friend Captain Marryat. How the two met is unknown but they appear to have been good friends by about 1833, and it was Stanfield who in 1841 introduced Marryat to Dickens.

On 19th September 1836 Stanfield arrived at Calais to begin the tour which in 1838 was to result in publication of his Sketches on the Moselle, the Rhine and the Meuse. In 1840 he painted three Italian pictures for Queen Victoria and completed work on Marryat's Poor Jack, the last full book to be solely illustrated by him. He had that summer been obliged by his health to seek country air and much of the work on Poor Jack was done at Northaw, Herts., where he rented a cottage near another friend, Joseph Marryat, the Captain's brother. The work also has a slight biographical curiosity in that the model for Jack was his and Rebecca's third son, James Field, then aged ten.

Despite his increasingly poor health, and in later years partly because of it, Stanfield continued to travel widely at home and abroad. His most famous though hardly most profitable expedition in England was that of October and November 1842, when the now inseparable Dickens quartet of 'Stanny'. 'Boz' himself, 'Mac' (Daniel Maclise, R.A.) and John Forster took off on a high-spirited and somewhat bibulous tour in Cornwall.

Two Portraits of John Forster. [Not in print version.]

His main sketching tours were more hard-working affairs but not necessarily less pleasant. The most important and well-documented was one which he made in Italy with his friend Thomas George Fonnereau. The latter, a charming gentleman of artistic tastes and independent means, was subsequently 'inspired by his friend C. S. Esqre, R.A.' to publish his own slim volume of sketches taken on the tour and humorously dedicate it to his companion.26

Leaving England in August 1838 they did not return until March of the following year; from Milan they travelled to Venice in the wake of the coronation progress of the new Austrian Emperor, Ferdinand I; from Venice they went via Rome to Naples. From there Stanfield sallied forth, in appalling weather, to all the traditional picturesque haunts — Amain, Sorrento, the Gulf of Salerno and the Naples vicinity itself. He then took a boat out to Ischia where sickness and bad weather temporarily imprisoned him over Christmas. The delay in returning to Naples proved a blessing in disguise, for without it he would have missed the eruption of Vesuvius which began on New Year's Day, 1839. He spent two nights on the mountain, 'inspecting the effects of the fire' before rejoining Fonnereau and beginning the journey home via Tuscany, the galleries of Florence, the Corniche and the Rhone valley. Subsequent large tours of which there is little record took him to Holland in 1843, into Southern France, the Pyrenees and Northern Spain in 1851 (with his wife and daughters) and to Ireland in 1856; from each of these resulted major Academy works, which he sold for large sums, and some of which within his own lifetime changed hands for even larger ones.

The 'Victory' Towed into Gibraltar 1854. Oil on panel, 46 x 70 cm. Collection: Guildhall Art Gallery, London. Reproduced courtesy of the City of London Corporation.

As the important pictures came rolling out — The Castle of Ischia (1841), The Day After the Wreck (1844), On the Dogger Bank (1846), The Battle of Roveredo (1851), Victory towed into Gibraltar (1853) and The abandoned (1856) — contemporary critics had no doubt that in Stanfield the country had a major landscape talent and, certainly after the death of Turner, the finest marine painter of the age.

One work of Stanfield alone presents us with as much concentrated knowledge of sea and sky, as, diluted, would have lasted any one of the old masters his life.27

If this oft-quoted judgement of Ruskin's overstates the case it nonetheless accurately represents contemporary opinion.

Left: Wreck of the 'Avenger. Watercolor, guache, and pencil. 10 1/4 x 15 1/4 inches. n.d., courtesy of Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester. Right: The Abandoned. Oil on canvas. 35 x 59 inches. Present location unknown.

With the acclaim came the responsibilities due to an eminent Victorian painter. Following his earlier works for Queen Victoria, Stanfield was one of the eight artists commissioned by Prince Albert in April 1843 to decorate the Garden Pavilion at Buckingham Palace with fresco subjects from Milton's Comus. The painters were to gain some slight prestige from the command but little else (their services were notoriously underpaid), and when completed the results were not particularly felicitous. Stanfield's fresco, the first of the series, was likened by Haydon to 'a diminished scene from the Lyceum'. Other duties were perhaps less of a chore. Although not (according to S. A. Hart) an 'Academy man', Stanfield served a total of eight years on the R.A. Council, twice when others had declined to take their turn. On the occasions when he was appointed to be among 'the hangmen' (the Committee of Arrangement for the annual exhibition) he seems to have performed his unenviable duties with considerable tact.

His opinion was also in demand elsewhere for sensible, though not erudite, opinions on art; between 1854 and 1865 he was one of those who regularly advised the great dealer Ernest Gambart, a good professional friend, on the arrangement of his London exhibitions. After the death of their old friend Turner in 1851 he, (Roberts and H. A. J. Monro formed the ad hoc committee which selected 102 of the Turner Bequest watercolours for their first exhibition at Marlborough House in February 1857. Stanfield's readiness to serve had even earlier brought him a modest but unique distinction. In the Painted Hall of Greenwich Hospital hung a great collection of naval pictures — those which were later to form the basic oil collection of the National Maritime Museum. By 1844 the Hospital Board had become anxious for their condition and asked Charles Eaststlake, as Secretary of the Fine Arts Commission, to recommend 'an 'artist of acknowledged' judgement and ability and especially conversant in Marine Subjects' to act as Curator of the gallery. Eastlake nominated Stanfield who was appointed in October with an honorarium of £100 per year and promptly set in hand substantial repairs to the Painted Hall and restoration of the works therein. He held the appointment until it lapsed in 1865, frequently mixing pleasure with business in bringing his friends to Greenwich and holding a festive 'Curator's dinner' there once a year.

Other obligations and honours followed, dependent on his recognised reputation and position; in the former category he was called before two Parliamentary Committees as an expert witness - that on Art Unions in 1844, and the controversial National Gallery Committee in 1853. In 1855 he had the pleasure of being in Paris to receive a First Class Gold Medal awarded for his five works at the Exposition Universelle, and in 1862 he was created a Chevalier of the Belgian Order of Leopold.

But if the surface appearances of Stanfield's later life showed him to be prosperous, successful and, according to Lady Eastlake, 'liked by all for his goodness and sincerity', there was also a more sombre side to his character only seen by his family and closest friends — that of a strict and increasingly religious paterfamilias. Stanfield survived all of his father's family, buried several of them and, as we have seen, lost his first wife in 1821. In 1838 Henry, the eldest son of his second marriage and a boy on whom he doted, died aged eleven; this tragedy and possibly his long stay in Italy later that year, seems to have turned him firmly back towards Catholicism, the faith which his father had abandoned. By 1842 he was closely involved with the passionate young Catholic architect Augustus Pugin, who incidentally was also an enthusiast for the sea. Pugin and Etty (a high Anglican) appear to have had a strong religious influence on him and he was often in the company of other Catholic artists like Mulready and J. R. Herbert. After 1841 Stanfield, with one or more of these, could often be found at Ramsgate where Pugin had close ties with the small Benedictine community and built his own house and church. For a while Stanfield contemplated moving there himself.

Although circumstantial evidence suggests Stanfield was a practising Catholic by 1842, he was baptized — or re-baptized — on 3rd October 1846 with the names Thomas Clarkson — a strange coincidence since the Reverend Thomas Clarkson, his original namesake, died only a week before, aged eighty-seven. This baptism took place in Hampstead, which he had long frequented either to sketch or to visit friends such as Constable, and where in that year he took lodgings for his health. Here he had also come under the influence of a well-known emigre priest, the Abbe Morel, founder of St. Mary's Chapel, Holly Place. Stanfield painted few portraits and their existence is therefore a sure sign of a close relationship with the sitter. That of Morel, an oil, is significantly his most finished work in this line. Nor were his Catholic connections purely parochial; one of his daughters married William Bagshawe, nephew of a Catholic Archbishop and later a judge, and Stanfield himself became a friend of the Cardinal Archbishop of Westminster, Nicholas Wiseman.

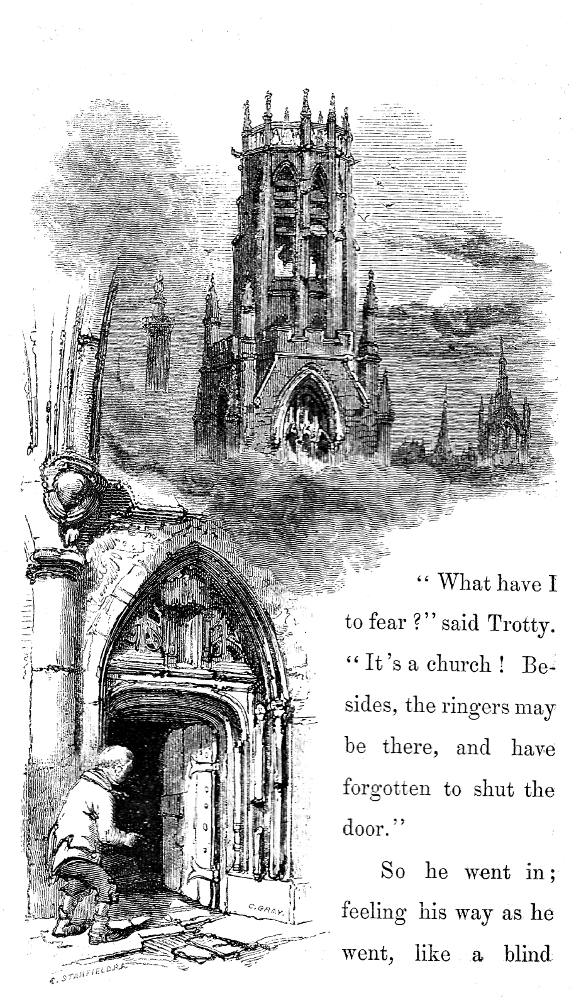

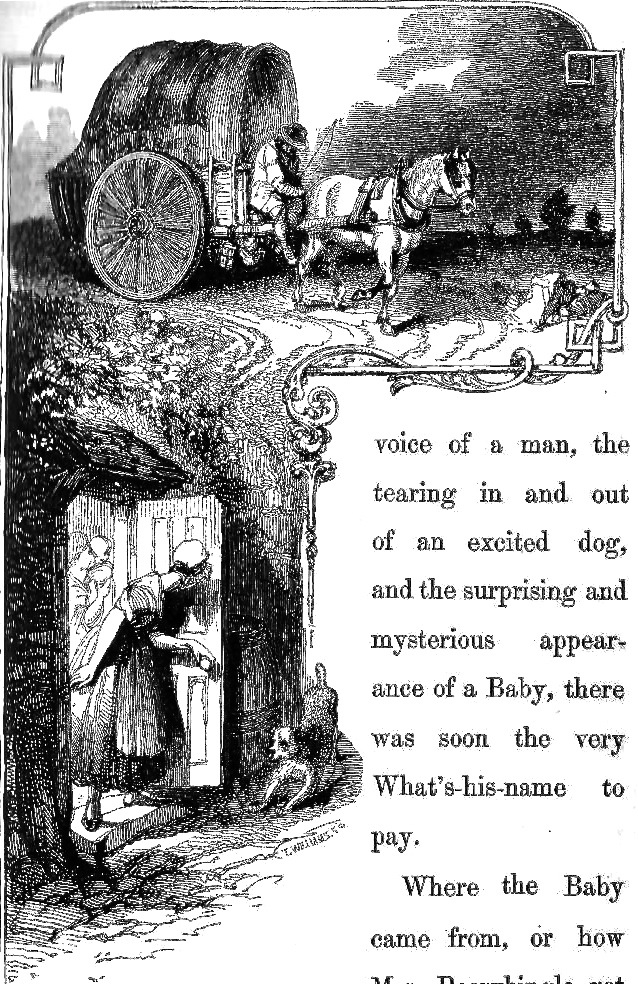

Three illustrations by Stanfield of Dickens's works. Left: The Old Church, an illustration for The Chimes. Middle: Will Fern's Cottage, an illustration for The Chimes. Right: The Carrier's cart an illustration for The Cricket on the Hearth. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

If Stanfield's peace of mind was ultimately assured by Catholicism, both the strength of his devotion to the faith, and the circumstances which may have encouraged this, show considerable disturbance in his personal life. His only known disagreement with Dickens occurred in 1846 when, having already illustrated his Christmas books The Chimes and The Cricket on the Hearth, he offered to do the same for xPictures from Italyx. However, on reading the early parts of the work his highly developed piety detected anti-Catholic sentiments in it and he withdrew the offer. Roberts too, with whom as they grew older Stanfield resumed a close friendship, learnt the importance of 'going quietly over the stones of poppery' if tranquility was to be preserved.28

Troubles in the family were more serious and seem in part to have been fed by his growing religious absorption, since not all his elder children appear to have converted with their father. Clarkson, his eldest son by his first wife, was by 1838 completely at loggerheads with his step-mother and became increasingly disturbed, unmanageable and even violent. Late in 1845 he was sent to the Marryats' farm in Norfolk for eighteen months but the Captain's healthy regime and the change of atmosphere had no permanent effect on his state of mind. Mary his sister, concerning whom Stanfield was very possessive, finally married in 1847, an event for which her father" displayed no enthusiasm and with which he never seems to have come to terms. By 1854 she and her brother were dead, both in their early thirties. James, Rebecca Stanfield's second son, emigrated to Argentina at about the same time, perhaps to escape the fraught atmosphere; John, his younger brother, fell into some unknown disgrace and also went overseas. George, trained as an artist by his father and strongly under his personal influence, had some success while Stanfield lived. After about 1870, however, changing fashion affected his patronage and he seems to have lost control of affairs, his wife's extravagance in particular; he died of liver disease in 1878, aged forty-nine. It was apparently only the younger children, two of whom (Francis and Raymund) became Catholic priests, who were all that a Victorian father might have required.

From 1832 Stanfield and his growing family had been living in the Mornington Crescent area but by 1847 their health was demanding the permanent change to fresher air that led him to contemplate a remove to Ramsgate. In that year however a chance arose to lease 'The Green-Hill' at Hampstead, a large mid-18th century house off the High Street, possessing a fine garden and a view down over fields towards Belsize and St. John's Wood. From the medical, religious and social point of view it was an ideal opportunity which Stanfield snapped up; at 'The Green-Hill', surrounded by a wide circle of friends, he spent the happiest and some of the most productive years of his life.

In the autumn of 1858 he and Roberts travelled to Scotland together, partly on a nostalgic tour but also for Roberts to be made a Freeman of Edinburgh and Stanfield to receive his diploma as an honorary member of the Royal Scottish Academy. At a dinner given for them by the Academy, Stanfield, in replying to his health from the President, explained how his friendship with Roberts

had weathered the vicissitudes of a pretty long career and had surmounted and survived the professional rivalries which had always accompanied them . . . Mr. Stanfield humorously described the rivalry as an earnest one. The managements ministering to the painters' professional enthusiasm . . until he believed both [Covent Garden and Drury Lane] were ruined by their scenic ambitions and rivalships. Then (he said) in ... the Royal Academy - our rivalries continued and do continue; but the friendship begun in youth had also continued and he believed those feelings of mutual affection and esteem would never cease.29

Before leaving Edinburgh he had his portrait painted for the Scottish Academy by Daniel MacNee, and at the end of 1860 he and Roberts marked their long association with the stage by jointly contributing the £250 needed to build one of the houses for 'decayed actors' in the new Dramatic College at Maybury. Stanfield in fact had not contributed his final work to the professional theatre until 1858 when he gave another old friend, Ben Webster, the act-drop design for his New Adelphi Theatre.

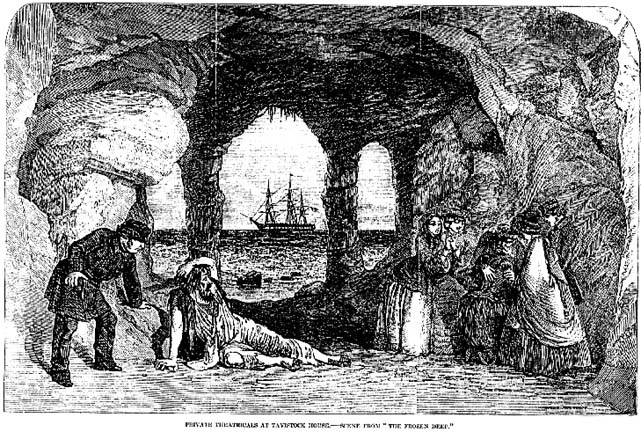

The Frozen deep from The Illustrated London News for 17 January 1857.

Inexorably, however, ill-health and age were limiting his activities. From about 1857 his leg gave perpetual trouble while general rheumatism and neuralgia frequently kept him housebound for weeks or left him incapable of holding pen or brush. In 1855 his doctor forbade him to paint large pictures, to which Stanfield's riposte was to paint all the scenery for Dickens' amateur production of The Lighthouse. Nevertheless, in the following year while he was painting The Frozen Deep for Dickens the latter regretfully told Miss Coutts that he thought infirmity and illness would prevent him from ever doing such work again.

Nothing could stop him painting however, and many even found the less precise touch of his smaller, late work a great improvement on earlier efforts. His travelling was now little more than local and after 1860 he was frequently found in south-coast watering places, where an old artist might gently potter around with a sketch book, rather than a young one seek sublime inspiration.

Stanfield himself was conscious how much he was becoming a survivor of his artistic generation; in 1861, telling the actor Charles Mathews how pleased he would be to see him at Hampstead to 'have a chat... about old times and old friends', he added (thinking of the long defunct Sketching Society) 'Alas to find myself the last of the lot, John and Alfred Chalon, Robson, Leslie, Cristal &c &c &c all gone ... I myself am very Shaky indeed'.30 The worst blow came on 25th November 1864 when Roberts, at the age of sixty-eight, collapsed in the street and died the same evening. From his daughter Stanfield received his old friend's palette and, in 1866, the dedication of his published Life but he was too ill to attend the funeral.

As S. C. Hall of the Art Journal helped him down the Academy steps at the exhibition of 1866, Stanfield gloomily told him that he did not expect to see him there again, though he very nearly defied his own prophecy. In the previous year he had moved to a smaller house in Belsize Park Road; there whenever possible during the winter of 1866, he worked on two pictures — A Skirmish off Heligoland, which harked back to his days in the North Sea traffic, and a small silvery panel of a deserted wreck on a shore, into which he may have infused a sense of his own situation. This he never finished.

Clarkson Stanfield, R. A. by William Frederick Lake Price (1810-1896). Albumen print. 1867. National Portrait Gallery, London (NPG P860).

When the Academy exhibition opened in May 1867 the Skirmish was hung in a good position in the East Room and his friends, in writing to congratulate him on it, expressed the hope that the onset of good weather would again see him out and about.

On 11th May however he was taken ill with stomach haemorrhage and began to fail; Dickens, whose last cheerful letter he had kept by him, received a hint from George Stanfield and came to see him for the last time. When he called again on the morning of Saturday 18th May, Stanfield was barely hanging on; at about half past five that afternoon he died 'quite peacefully' at the age of seventy-three.

Last modified 23 February 2015