Click on the images to enlarge them and for more information about them, and for their sources and terms of reuse (if permitted).

In the Victorian era, the black subject became a point of interest within the artistic community. As Jan Marsh explains, ‘African complexions required different pigments’, demanding a ‘careful attention to exact hues and [an] understanding of how light reflects from dark skin’ (15): artists found dark-skinned models fascinating to paint while allowing them to demonstrate expertise in painting their skin tones. However, while they could showcase their talents in this way, artists were less interested in engaging with the cultures that their black subjects embodied.

Black subjects were used mainly to illustrate social comedy and exotic fantasy, at the same time serving as contrasts with white subjects, often in ways that reinforced the greater value of the white female icon. Indeed, artists deliberately combined black subjects and white subjects to show the contrast between the two and to highlight the idealised purity of the European or Anglo-Saxon subject. Of course, these depictions reveal the racist attitudes of nineteenth century England. Most black subjects in nineteenth century art (particularly black females) were perceived as objects rather than subjects. As one critic notes in 1867, underlying racial prejudice permeated art at the time: ‘A black is eminently picturesque, his colour can be turned to good account in picture-making’ (Art Journal 248).

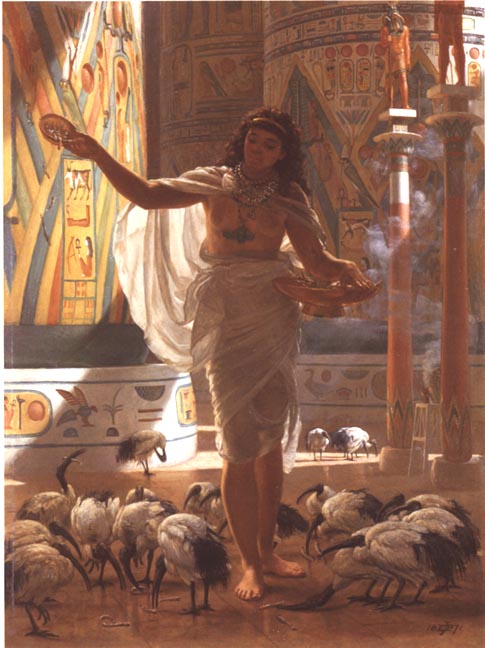

Two examples of black subjects in Victorian painting. Left: Rossetti,The Beloved, with Eaton in the right background. Right: Poynter, Feeding the Sacred Ibis in the Halls of Karnac.

Reduced to these terms, black models are practically erased from the record. Nevertheless, it is important to know the experiences and sufferings of such an individual in order to ‘better understand the paintings in which she appears’ (Ferrari 3). As Elizabeth Prettejohn has noted: ‘The individuality of each model … persists as an identifiable element in the final work’ (26). One particular model, who features in Solomon’s The Young Teacher (1861) is Fanny Eaton, whose life remains a mystery today – even to her descendants.

Rebecca Solomon’sThe Young Teacher.

Eaton was Jamaican born, and a child of mixed-race parentage. She appeared in numerous Pre-Raphaelite works from around 1859 to 1867, making her first public appearance in Rebecca’s brother Simeon’s work The Mother of Moses (1860) at the Royal Academy. Little is known about her and her creative and working relationships with the Pre-Raphaelites, other than that she may have been spotted on her way to work (she worked as a housekeeper lodger) whilst the Solomons may have been walking to their respective art schools.

Simeon Solomon’s representation of Eaton in The Mother of Moses.

As her great-grandson Brian Eaton points out in a conversation with the present author, Fanny’s story is a sad one, and one that to some extent runs parallel to Rebecca’s. There are no known photographs of her, nor do we know of any potential works she may have produced. However, Eaton’s physical features as depicted in Pre-Raphaelite art give an indication of her appearance and ethnic background. Eaton’s ethnicity was discussed in a letter written by Rossetti to Ford Madox Brown in 1865: ‘She isn’t Hindoo … but mulatto’ (Rossetti 2:566). Of course, the term ‘mulatto’ was and is still considered pejorative. It is a term that alludes to a mule – a hybrid of a horse and donkey – and always carried racist and derogatory connotations. Indeed, Fanny seems to have been regarded as of the lowliest status. According to Brian Eaton, she does not even have her own resting place and is buried with seven other unrelated adults in Hammersmith in an unmarked grave. He concluded that Eaton would have been on the fringes of society, and not been able to take part in the lives of the other women who moved in the Pre-Raphaelite circle.

In fact, black women such as Fanny Eaton would have been more excluded from society than any other social category. Nonetheless, few black models were in greater demand: well-known, she sat for Rebecca’s brother Simeon, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Fred Sandys and Albert Moore. Although representations of idealised beauty in British art were typically ‘white’, Eaton was an incredibly influential muse in Pre-Raphaelite art, as she was often considered as a mesmerising woman to paint. Rossetti rather hypocritically added in his letter to Ford Madox Brown a complement to her ‘very fine head and figure’ (Fredeman 322), and he also equated her beauty to that of Jane Morris, that famous female Pre-Raphaelite who was one of Rossetti’s prime inspirations.

In Rebecca’s painting, Fanny appears as the protagonist, a dark-skinned tutor educating two young white children within a middle-class domestic setting. Eaton’s character holds a white, fair haired toddler on her lap as they sit behind a card-table. On the woman’s other side leans an older, golden haired child who is pointing at the illustrated book presented to her; and behind the trio stands a bookcase, which suggests that the children come from a well-read family.

These details establish the setting and milieu, but Solomon focuses on the difference between the teacher and the two children. These oppositions are registered in a variety of ways. The physical differences are clear. The two young children would have been perceived by contemporary viewers as the embodiment of purity, while Eaton’s character would have been perceived as a focus of prejudice and disapproval. The trio’s attire also signifies ethnic difference. While the young tutor wears a shawl worn in a way that evokes an Asian or Middle-Eastern style, over a fashionably Victorian lady’s frock, the two children are dressed in fine bourgeois style typical of their class. Viewers would have noted these difference between them, as attitudes towards other cultures and races were as alienating and derogatory as they were towards gender and social class.

Tellingly, Victorian art critics argued that the tutor in the painting, assumed to be in charge of the children, is their intellectual inferior; they further suggested that the black character was the ‘recipient of the title’s teaching, rather than the teacher herself’ (Gerrish-Nunn 769). Astonishingly, they assumed that the white children possessed more intelligence or knowledge than the adut (black) woman. They made this point especially in relation to the subjects’ facial expressions and body language, which seemed for many to suggest a basic racial inequality. For example, The Critic’s reviewer regarded the girl as the teacher and noted the woman’s ‘semi-intelligent type of countenance’ (524).

However, such prejudiced readings do not necessarily accord with the artist’s intention. Solomon perhaps presents this difference, not to emphasise the so-called ‘virginal purity’ of the two young white girls in contrast to their tutor, but to demonstrate to her viewers how marginalised figures such as Eaton were categorised and exiled by society because they were unlike. Rebecca may have chosen Eaton as an emblematic type who stood for all different races – and may have symbolized the artist’s own difference, as a Jew living in an Anglo-Saxon society, who may have endured ethnic prejudice because of her Jewish heritage.

Such a view is supported by the composition itself. The children's tutor displays the traits of a liberated and intellectual young woman. As previously discussed, young women would not be expected to display greater intelligence than their male peers. Far less would a woman of colour be expected to surpass a white person in matters of intellect. Judith Butler’s work gives us the tools to view attributes such as gender, class and race as hegemonic, subjectifying norms rather than fixed or innate aspects of identity, which calls into question their ontological status.

Therefore, the mutual theorization of race, gender and social class is an epistemological problem in scholarship. The historical tendency has been to see white women as the ‘presumed natural subjects of women’s and gender studies’ (Sarat & Ogletree 168). As feminists of colour have frequently argued, universalising the ‘political interests, privileges and burdens… experienced by white women, fails to address the experiences and political interests of women of colour’ (Sarat & Ogletree 168). We can no longer rely on placing these ‘constructs’ of identity in the same conversations with each other, as the white female subjects discussed in Solomon’s other paintings cannot be discussed in line with Solomon’s young teacher. Whatever their sufferings, they do not represent the same experiences that some black women and other marginalised figures in Victorian society would have had.

In short, Solomon deliberately chose to paint and put a black subject in the fore rather than a white subject. This was perhaps to provide the woman of colour with her own platform. Looking at The Young Teacher, Solomon may have painted the emotional closeness of the trio to promote a transcending of racial and social boundaries, due to the close relationship between the two young girls and their teacher. Solomon may have depicted these three female subjects together to challenge pre-existing attitudes towards women of colour. The three appear united in their close embrace, which may well be exactly what Solomon wanted to promote for young women, regardless of their racial, ethnic and gender identity. It would seem that Solomon was encouraging women to unite to overcome the patriarchal biases of society that kept them apart.

Bibliography

Note: Some of the information contained in this account is based on an email conversation between the author and Mr. Brian Eaton, Fanny Eaton’s descendant.

The Art Journal (1867).

Butler, J. Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity. London: Routledge, 1999.

Chadderton, C. Judith Butler, Race and Education. UK: Springer Publishing, 2018.

Ferrari, R. ‘Fanny Eaton: The ‘Other’ Pre-Raphaelite Model.’Review of the Pre-Raphaelite Society 12:2 (Summer 2004): 23– 36.

Gerrish Nunn, P. ‘Rebecca Solomon’s “A Young Teacher.”’ The Burlington Magazine 130 (October 1988): 769–70.

Hooks, B. Black Looks: Race and Representation. London: Taylor & Francis, 2014.

Marsh, J and Bressey, C. Black Victorians: Black People in British Art 1800–1900. Farham: Lund Humphries, 2005.

Prettejohn, E. Art of the Pre-Raphaelites. UK: Harry N. Abrams, 2007.

‘Review.’ The Critic 23 (1861).

Reynolds, S. The Vision of Simeon Solomon. Stroud: The Catalpa Press. 1984.

The Correspondence of Dante Gabriel Rossetti: The Chelsea Years, 1863-1872, Prelude to crisis: 1861—1867. Ed. W. Fredeman. Suffolk: D.S Brewer

Rossetti, D.G. Letters of Dante Gabriel Rossetti. 4 Vols. Eds. Doughty, O. and Wahl, J.R. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1965. Vol. 2.

Sarat, A. and Ogletree, C. Racial Reconciliation and the Healing of a Nation. New York: NYU Press. 2017.

Created 10 October 2021