Photographs by the author unless otherwise noted in the caption. The rest of the images were kindly supplied by the exhibition's press office, or the Timorous Beasties company, for review purposes. You may reuse the author's own photographs without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and usually for more information about them.]

[Detail from] Ruskin's Study of Moss, Fern and Wood Sorrel, upon a Rocky River Bank, 1875-79, © Guild of St George, Museums Sheffield.

London's world-class galleries continue to vie with each other to stage ever more dazzling shows. Yet visiting an exhibition in a more intimate venue can be more relaxed, and equally rewarding. Two Temple Place was the perfect choice for presenting John Ruskin to a modern audience: its compact display spaces are ideal for focusing attention on his detailed studies and other small items. At the same time, without swamping these delicate productions, carefully selected works by other artists demonstrate his influence across a whole range of fine and applied arts. These items too appear to their best advantage in the rooms of this restored mansion, with its beautifully crafted interiors.

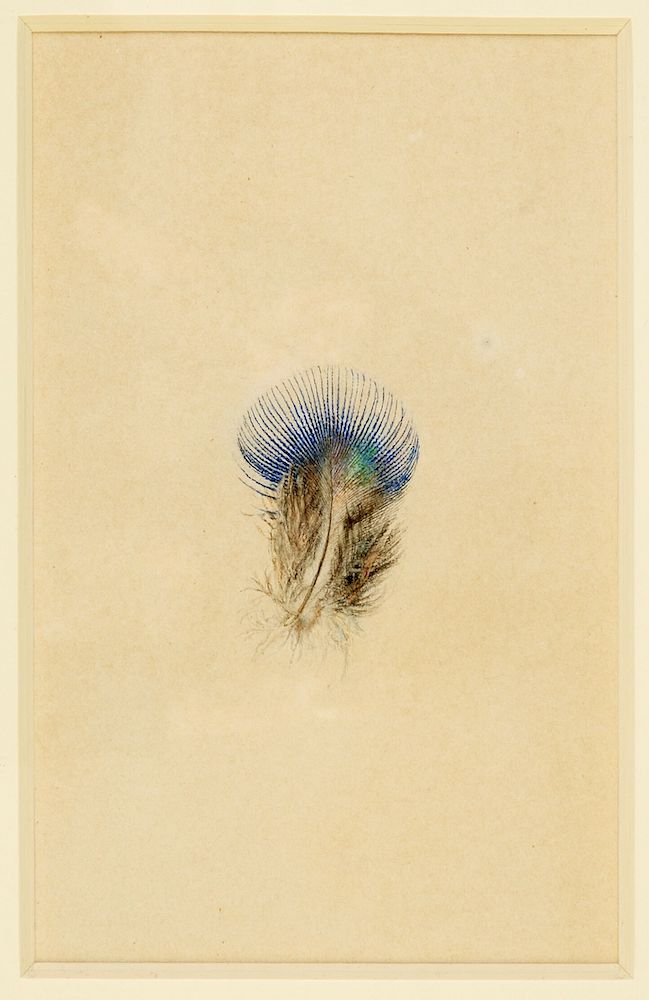

Left: Study of a Peacock's Breast Feather ©Guild of St George, Museums Sheffield. Right: Edward Lear's Macrocercus Aracanga (Red and Yellow Macaw).

Ruskin was born on 9 February 1819, and, in fitting celebration of this bi-centenary year, there are around two hundred items on show here. The vast majority have been brought down from Sheffield, where Ruskin himself had assembled a collection expressly to inspire local working people. Like so many Victorians, he was an avid collector. He had, for example, a wonderful library of books on ornithology, and one grouping in the first room reflects his special love of birds. He was also a passionate communicator. As one information panel here explains, he spoke arrestingly, as if through a megaphone. But in these representations of birds we see him speaking equally persuasively through his art, in studies of an avocet, a cockatoo, a peacock's breast feather, and so on. Shown alongside his own meticulous studies are examples of the kind of work by other bird illustrators whom he admired or inspired, including Audobon and Edward Lear. Lear's parrot makes a wonderful splash of colour in this quiet context.

Not for nothing is this exhibition entitled "The Power of Seeing." Another information panel quotes from Ruskin's The Relation of Art to Use, to the effect that "you cannot so much as once look at the rufflings of the plumes of a pelican or carefully draw the contours of the wing either of a vulture or a common swift, or paint the rose and vermilion on that of a flamingo, without receiving almost a new conception of the meaning of form and colour in creation." To Ruskin's mind, not only nature itself, but also the very act of observing it closely and turning it into art, enriches the spirit and enhances our sense of wellbeing.

Left: The Kapellbrücke, Lucerne, by Ruskin. Right: J. W. Bunney's Façade of San Marco, Venice.

This is further illustrated in studies of scenery, like his own Kapellbrücke, Lucerne (1861), on loan from the Ashmolean in Oxford, as well as in fine sketches of Gothic details in architecture, especially in his beloved Venice. In this connection, a rare treat is to see J. W. Bunney's enormous 7'5" oil painting of the Western Façade of San Marco (1882), demonstrating as it does the two men's shared fascination with the "stones" of Venice. Naturally, Turner, whom Ruskin considered "beyond all doubt ... the greatest of the age," is represented here too. One of the works on show is his Venetian Festival (c.1845). Nearby is William Parrott's much-loved depiction of a stocky, top-hatted Turner, oblivious to those around him, putting a last touch to a painting on "varnishing day" at the Royal Academy.

William Parrott's J.M.W. Turner on Varnishing Day.

Upstairs, the exhibition showcases the variety of Ruskin's interests, and the crafts that he encouraged, from furniture to metalwork to sculpture — and more. These diverse items are numbered. In lieu of display labels, visitors are encouraged to refer to lists which offer more information on each one. The exhibits here range from the other "stones" that Ruskin loved (geological specimens, and wonderfully glistening minerals) to pages of illustrated books, furniture handcrafted for the original Guild of St George museum that Ruskin founded, and sculpture by his protégé, Benjamin Creswick. All repay close scrutiny. All bear out Ruskin's faith that the craftsman who is suited to his work, and appreciated for it, not only expresses himself through what he produces, but in so doing adds to the sum of beauty in the world.

Left: Some of the minerals on display at the exhibition. © Guild of St George, Museums Sheffield. Right: The Blacksmith's Forge, work by Benjamin Creswick on a subject dear to his heart.

This exhibition achieves something special, partly just by bringing down from Sheffield a small sample of the Guild of St George's collection there. Many might not be aware of the Guild's continuing work, which allows Ruskin's ideas to inspire new generations in a variety of arts and crafts. Of course, even without such a focus, this happens elsewhere too. Not to be forgotten are some contemporary installations in Two Temple Place itself, showing how Ruskin's influence has travelled down through the years. Particularly appealing are the lampshade and wallpaper hangings at the top of the stairs, produced by the Timorous Beastie Company, and sporting their floral and birds-'n-bees designs: the panels in particular are reminiscent of the collaboratively painted panels in Wallington where Ruskin himself was so actively involved. They look as if they belong here. It will be sad to see them go at the end of the exhibition!

©Timorous Beasties. In this installation, the lampshade is mirrored on the outside, with their Birds-'n-Bees design inside. On the wall behind are the company's Winchester and Indie wood veneer wallpaper panels.

There is always a place for smaller galleries, especially one with as much character as Two Temple Place (another inviting venue is the Watts Gallery in Compton, Surrey — Watts is also represented here). Much to both the artist's and the curator's credit, the Tate's current Burne-Jones exhibition manages to maintain a high level of excitement throughout, but that is not always the case with the larger galleries. Here, there is plenty to see, but not too much to take in, and time to think about how it all expresses Ruskin's larger views. No need to pre-book or join a queue, no timed entry-slots, no pressure to move along once inside — and it's free, just as Ruskin would have wished. As our chief editor and webmaster George Landow says, Ruskin "possesses more than historical importance" (88). His influence can still change lives. To look closely at the exhibits is to complete the vital process of "seeing" by which the eye perceives, and the heart truly relishes, the "form and colour in creation" through the lens of art.

Related Material (a few examples of other artworks at the show)

- Ruskin's Study of a Spray of Dead Oak Leaves

- J. W. Bunney's South West Corner of the Doge's Palace, Venice

- John Brett's Mount Etna from Taormina, Sicily

Bibliography

Landow, George. Ruskin. Routledge Revivals ed. Abingdon, Oxon.: Routledge, 2015.

Created 10 February 2019