O just and faithful knight of God!

Ride on! The prize is near.

So pass I hostel, hall, and grange,

By Bridge and ford, by park and pale,

All arm’d I ride, whate’er betide,

Until I find the holy Grail.

— Sir Thomas Malory, Morte D’Arthur [quoted Bell, 21]

n a spirit reminiscent of medieval knights riding in search of the Grail, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and William Morris sought after a stylistic language representative of their commitment to artistic truth and beauty. The lives of these three artists intersect at the juncture marking the disintegration of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the subsequent incarnation of the movement’s second phase. In the 1860s, the PRB’s second generation of visionaries emerged as a movement opposed to the original Pre-Raphaelite stylistic program. Rejecting the “bright and factual style of the early years, the poetic intensity, the interest in modern subjects and the minute detail,” Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris conceived of an evolved Pre-Raphaelitism responsive to the Aesthetic Movement and its mass appeal among wealthy consumers (Treuhertz, 101). The idea of decoration for its own sake initiated a reinvention of the Pre-Raphaelite composition and its use of pictorial space. The influence of the Aesthetic Movement, however, did not entirely wipe out the remaining traces of the PRB’s ideological lineage. Drawing inspiration from the imagination and literary sources, especially those idyllic of the medieval age, the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism romanticized their subject matter with the intent of spiritual transcendence. As a result of Burne-Jones and Morris, and Rossetti’s association, the newly reinvented Pre-Raphaelitism succeeded in its synthesis of the spiritualistic heart of its parentage with innovate stylistic devices of the Aesthete.

n a spirit reminiscent of medieval knights riding in search of the Grail, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, Sir Edward Burne-Jones, and William Morris sought after a stylistic language representative of their commitment to artistic truth and beauty. The lives of these three artists intersect at the juncture marking the disintegration of the original Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the subsequent incarnation of the movement’s second phase. In the 1860s, the PRB’s second generation of visionaries emerged as a movement opposed to the original Pre-Raphaelite stylistic program. Rejecting the “bright and factual style of the early years, the poetic intensity, the interest in modern subjects and the minute detail,” Rossetti, Burne-Jones and Morris conceived of an evolved Pre-Raphaelitism responsive to the Aesthetic Movement and its mass appeal among wealthy consumers (Treuhertz, 101). The idea of decoration for its own sake initiated a reinvention of the Pre-Raphaelite composition and its use of pictorial space. The influence of the Aesthetic Movement, however, did not entirely wipe out the remaining traces of the PRB’s ideological lineage. Drawing inspiration from the imagination and literary sources, especially those idyllic of the medieval age, the second wave of Pre-Raphaelitism romanticized their subject matter with the intent of spiritual transcendence. As a result of Burne-Jones and Morris, and Rossetti’s association, the newly reinvented Pre-Raphaelitism succeeded in its synthesis of the spiritualistic heart of its parentage with innovate stylistic devices of the Aesthete.

By 1860, critics and members of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood acknowledged the definitive end of the original movement and, in particular, its stylistic principle of microscopic realism, though in fact it continued to influence English painting for the rest of the century. From the wreckage of the PRB’s disbandment grew a second phase of the movement that placed the general idea of beauty over the specific stylistic dogma of the PRB. “In place of the overriding concern with nature and detailed symbolism, there was a new concern with aesthetic ideals” (Barne, 99). Whereas the PRB held fast to a curriculum of “romantic idealism, scientific rationalism and morality,” the emergent Aesthetic Movement provided a significantly more diversified program; grounding itself in the simple, yet vaguely defined criteria of formal order and the visually beautiful. Deeply affected by the Aesthetic Movement, the reincarnate phase of Pre-Raphaelitism adopted a “style of soft colors, and lack of definition, of imaginary visions and mysteries, of decorative outlines and patterns”; this style of painting “was not a representation of a realistic scene, but an imagined idea, presented as a beautiful artifact.” Moreover, the coming together of Burne-Jones and Morris initiated the formative stages of Pre-Raphaelitism’ next life, which would ultimately consolidate as a movement under the guidance of Rossetti.

In 1853, Burne-Jones and Morris crossed paths while students at Exeter College, Oxford. Similarly interested in medieval stories and legend, the young men also shared a deep-rooted religiosity. Intending to take their religious Orders, Burne-Jones and Morris underwent a sudden moment of conversion inspired by Ruskin’s Modern Painters and Edinburgh Lectures. Through these texts, Morris and Burne-Jones learned of the PRB and, as described by Ruskin in Lectures, their ““uncompromising truth,’ which in itself was a moral quality” (Fitzgerald, 30). Furthermore, the Pre-Raphaelite publication The Germ, seemed to offer Morris and Burne-Jones a “brotherhood [, akin to the spiritual union of priests,] whose aims were in harmony with theirs, men who, like them, had felt the breath of great awakening . . . calling upon the spirit to shake itself free from conventionalities and . . . to return to nature ‘in all simplicity of heart,’ as the true source of life and of art” (de Lisle, 19-20).The qualities of sanctity and honorable purpose underlying the Pre-Raphaelite philosophy appealed to Morris and Burne-Jones’ religiosity, as well their romantic idealization of a the medieval. After viewing Rossetti’s watercolor Dante drawing an Angel on the First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice in 1855 (Whiteley, Morris and Burne-Jones henceforth dedicated their lives and careers to spiritual fulfillment through the visual arts; with Rossetti as their chosen mentor.

Although critical to the formation of the PRB, Rossetti, from the beginning, operated as “an individual painter, inspired by an inner poetic vision” (Barne, 45). Less technically proficient than other members of the Brotherhood, Rossetti experimented freely with his painting materials; finding watercolor easier to work with than oils. Rossetti’s passion for literary subject matter, in particular medieval sources, distinguished the artist’s work from the modern subjects championed by his colleagues (Barne, 45). Morris and Burne-Jones identified with Rossetti’s enthusiasm for mediaeval and un-modern subjects, which evoked a sense of implicit spirituality. At the time of Morris and Burne-Jones’ introduction to Rossetti, the veteran Pre-Raphaelite had stylistically evolved from the unstructured quality of his earlier paintings. Still romantic and literary, Rossetti’s works of the 1860s replaced imprecision with heightened awareness of the composition’s overall aesthetic value. Rossetti’s Dante drawing an Angel reflects the artist’s blend of Pre-Raphaelite romanticism with the popularly received qualities of the Aesthetic Movement.

Typical of his paintings, Rossetti’s Dante drawing an Angel derives from a literary source, a scene from Dante’s Vita Nuova (Whiteley, 46). Stippling layer upon layer of dramatic color, Rossetti’s resembles the coloration of Italian Renaissance painters Titian, Giorgione and Palma Giovane (Wood, 96). In the composition’s center, Rossetti situates four figures captured in the brief transitory moment between actions. Rossetti organizes his figures in a frieze-like arrangement; this pictorial structure accentuates their flatness. To the far right, Dante kneels on the floor with a drawing of his beloved Beatrice in hand. Brought down from the heavens and back to work. Dante stops his work and dazedly looks at his company. In the background, a horizontal band of angel heads lines the wall. This purely decorative feature reflects the interests of the Aesthetic Movement, as well as Rossetti’s willingness to incorporate them into his paintings. Nevertheless, Dante drawing an Angel reads as a poetic blend of medievalism and “romantic archaism” (Esther Wood, 117). The painting foreshadows the crossover between Pre-Raphaelitism and the decorative aspect of the Aesthetic Movement. As evident in Rossetti’s painting, this stylistic intersection entailed “the simplicity of forms, unsophisticated construction and the pictorial and heraldic enrichment of flat surfaces” (Watkinson, 171). Enthralled by Dante drawing an Angel, Morris and Burne-Jones sought out the guidance of Rossetti. Their creative union inaugurated the second chapter of Pre-Raphaelitism.

During the summer of 1855, Morris and Burne-Jones traveled to Northern France to the study the churches. As a result of this tour, Morris decided to become an architect after completing his studies at Oxford. Burne-Jones, on the other hand, resolved to leave Oxford without a degree and dedicate himself to painting. Accordingly, the inexperienced painter sought out the guidance of his hero Rossetti (Watkinson, 163). By some fortuitous circumstance, word reached Burne-Jones of Rossetti’s residence in London. In 1856, Burne-Jones contacted Rossetti, who flattered by his admirer’s praise, agreed to educate the young painter. Traveling to London on weekends, Morris joined Burne-Jones in his apprenticeship under Rossetti.

To give the young men a better understanding of the art practice, Rossetti opened his studio to them “so that he might watch the progress of the pictures which were on the easel, and a number of the master’s drawings and studies were lent to him to help him in his work at home” (Baldry, 27-28) With a primary focus on the method of his own works, Rossetti’s teaching curriculum stressed the idea of painting as a mode of self-expression. Although encouraging his students to work against the grain of academic tradition, Rossetti advised his pupils to master the technical side of painting; this concern was practically non-existent in Rossetti’s early works. As evident in Dante drawing an Angel, Rossetti had begun “to understand that romantic themes, emotional gestures, could not of themselves make great paintings; that the painting conveyed ideas, induced emotional responses, by virtue of its conversion of the facts of vision into articulate formal arrangements, and that this creates style; not style, art” (Watkinson, 34). The Aesthetic Movement and its emphasis on formal order undoubtedly encouraged Rossetti to adopt a more legible, decoratively enhanced style. Despite his stylistic transformation, Rossetti did not compromise the emotional spirit of the poetically charged medieval subjects sp distinctive of his painting. Instead, Rossetti merged the design component of the Aesthete with his romantic sources of inspiration. Enjoying the company of fellow medieval enthusiasts, the impulsive Rossetti invited the two inexperienced artists to challenge their abilities.

In 1857, Morris and Burne-Jones returned to Oxford, but in the company of Rossetti and his circle artist friends. Initially commissioned to paint Newton gathering pebbles on the Shore of the Ocean of Truth in Benjamin Woodward’s University Museum, Rossetti, upon his arrival, resolved that he could not paint such a subject. As a compromise, Rossetti offered, with the aid of his companions, to decorate the walls of the Debating Room with ten scenes selected from Sir Thomas Malory’s Morte D’ Arthur (Whiteley, 42). Inspired by Rossetti’s admiration of Italian art, the group carried out their project in the form of fresco. “Stippling with fine brushes to follow the practice in medieval manuscripts,” the painters utilized “a pointillist effect” encouraged by Rossetti (Mander, 172). The Arthurian murals, full of “romantic force and imaginative fervor,” brought to life spirit of a golden age” (Esther Wood, 143).

Apprehensive of his inexperience, Burne-Jones accomplished the large-scale project with incredible skill and imagination. In his Nimue brings Sir Peleus to Ettarde after their Quarrel, Burne-Jones transformed the dull wall-space into a romantic display of stunning technical ability. On the contrary, Morris executed his Sir Palomides’ jealousy of Sir Tristram and Iseult with figures “poorly and clumsily painted, but the background of leaves and flowers” revealed his aptitude for design (C. Wood, 110). Morris’ grotesque decoration on the Debating Room’s ceiling also indicated the same (E. Wood, 144). A year after its conception, the creators of the Oxford murals were abandoned their frescos to fade away. Despite the project’s incompletion, the experience of working alongside Rossetti and established artists proved invaluable for the artistic self-awareness of Morris and Burne-Jones. Rossetti’s praise and perhaps the realization of his immense potential reconfirmed Burne-Jones’ already fervent proclivity for painting. Morris, on the other hand, redirected his concentration on the mastery of expression through design.

During his participation in the Oxford murals, Morris painted the awkward Queen Guinevere. A “strangely flat portrait, which [Morris] referred to as “the brute.’” Queen Guinevere ultimately comes across as an uneasy imitation of Rossetti (Barne 94). Uncomfortably posed, the expressionless Guinevere inspires little in the imagination of the viewer. Employing an Italian inspired color scheme, Morris looses the strength of his subject in a confusion of dark browns and reds; the composition lacks the emotive coloration found in Rossetti’s paintings. While Queen Guinevere exposes the artist’s lack of mechanical proficiency as a painter, Morris succeeds in his elaborate patterning of Guinevere’s dress. Identifying his talent for design, Morris gave up the medium of painting for that of design.

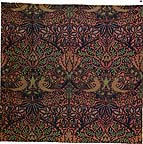

In 1861, Morris co-founded Morris, Marshall, Faulkner & Co., nicknamed “the Firm,” which combined medieval imagery with decorative aestheticism. In the following decades, Rossetti and Burne-Jones would make contributions to Morris’ design company. Similar to the days of the Oxford Murals, Morris worked in a collaborative work environment. “Responsible for designing and painting interiors and for manufacturing high quality furniture, stained glass, tiles, tapestry, textiles and wall-paper, embroidered hangings and metal work,” the Firm committed themselves to the production of aesthetic goods available to the Victorian consumer (C. Wood, 93). “The cult of Medievalism and the High-Church Anglican and Anglo-Catholic movements which were in full flower in mid-Victorian Britain . . . provided the company with a ready market for its products” (Cody). By the 1870s, Morris established a more business-oriented Morris & Co. geared toward the manufacturing of design items for consumption. To Morris, his merchandise would beautify England’s public buildings and homes while proliferating the Pre-Raphaelite idea of beauty as a spiritual truth; this ideal would translate throughout Morris’ body of design work. In his 1879 Dove and Rose, Morris harmoniously unites the romanticism of Rossetti with the applied ornamentation of the Aesthetic Movement.

Designed as a textile, Morris’s Dove and Rose evokes a mood of warmness and comfort. The interweaving flowers and foliage tenderly embrace the doves. By enclosing the birds and their natural paradise within the dark lines of a heraldic design, Morris gives his pattern structure and clarity. Similar to Rossetti, Morris integrates his piece with an implied spiritualism conveyed through medieval subjects. Bringing to mind the Garden of Eden, Dove and Rose reminds the viewer of a harmonious past lost forever. Thus, Morris’s romantic design “reflects his belief that the Mediaeval Past held all of the values — heroism, chivalry, beauty, and love — which made life worth living; all the values which his own age” seemed to lack (Cody and Landow). Furthermore, Morris uses vivid, Italian-inspired color to complement these ideals. Morris offsets the burnt orange and red coloration of the background with the cooling hues of green and blue. Rossetti’s Beata Beatrix, painted from 1864-70, employs a similar color scheme (C. Wood, 96). For both Rossetti and Morris, the richness and intensity of this juxtaposition heightens the emotional quality of the composition, but does not detract from its clarity. Anticipating the overlap between the Aesthetic Movement and Pre-Raphaelitism, Burne-Jones’1860 Sidonia von Bork merges Morris-like design with medievalism characteristic of Rossetti’s paintings.

Inspired by Wilhelm Meinhold’s tragic romance Sidonia the Sorceress, Burne-Jones’ Sidonia von Bork captures the narrative’s central character in a moment of concentrated deliberation. Sidonia’s beauty captivates the attention of every man. She returns her admirers’ attention with cruelty. In profile view, the deceptive Sidonia intensely, almost aggressively stares in the direction of the viewer. She clutches her necklace, which initially reads as act indicative of fragility. The tightness of her fist, however, suggests a hostile element to this pose. Burne-Jones’ stiffly renders Sidonia, as well as the background figures; the frieze-like posture of the figures reflects Rossetti’s manner of compositional structure. The figure of Sidonia embodies the popular Pre-Raphaelite figure of the femme fatale; she is exceedingly beautiful on the surface, but internally rotten to the core. Undoubtedly inspired by Rossetti’s depiction of women, Burne-Jones endows Sidonia with luxurious, golden hair. Imitating Rossetti’s Italian inspired coloration, Burne-Jones uses a rich palette of brown, red, orange and blue, which creates an ominous mood. The “elaborate finish of the dusky background with its bottle-glass window and groups of attendants, and in particular the strange white dress of the principle figure, all overlaid with curious, writhing, serpent-like knots of black velvet, are all exactly as such Rossetti might have conceived and painted them” (Bell, 24). The surging, patterned design of Sidonia’s dress demonstrates Burne-Jones’ willful incorporation of intricate ornamentation for aesthetic purposes; the parallel with Morris’s work is most evident here. Sidonia von Bork epitomizes Pre-Raphaelitism’s move toward a more aesthetically driven composition. Rossetti’s The Blessed Damozel similarly responds to this trend.

From 1871 to 1879, Rossetti painted The Blessed Damozel as a visual accompaniment to his similarly named poem (Wood, 101). This painting reveals Rossetti’s full integration of the decorative aesthetic into the whole of the pictorial space. In contrast to his earlier experimentations, Rossetti’s Blessed Damozel allows ornamental design to dictate its compositional structure. In this composition, Rossetti reinvents the femme fatale; her intentions are that of love rather than cruelty (Wood, 113). With her head turned in profile view, the recently deceased woman’s sullen face expresses a sense of longing. Rossetti “depicts her in heaven, surrounded by re-united lovers, and gazing down at her own love, still imprisoned on earth. Even though love is everlasting, a mood of sadness and yearning pervades the painting” (Treuherz, 107). The woman looks down on her lover, who likewise piers up in her direction. The pictorial separation of the lovers accentuates the painting’s melancholy atmosphere. Additionally, Rossetti creates a sharp distinction between heaven and earth through decorative design. Symmetrically framed by blossoming flowers, the woman enshrouds herself in memories. Above her, Rossetti patterns the image of the two separated lovers in a tight embrace; the prominence of this repetition creates a striking contrast in comparison to the lovers as solitary figures. Beneath the heartbroken woman, three portraits represent the stages in her life, from childhood and adolescence to adulthood. Beyond the limits of the woman’s celestial world, her lover sits in a bucolic setting. In this portion of the composition, Rossetti uses dark colors of green and brown to distinguish earth from the bright tones of heaven. With a halo of seven stars encircling her head, the woman sits on her heavenly chair and patiently waits for her lover’s arrival. Rossetti’s Blessed Damozel visualizes “the passionate, insatiable craving of the faithful heart for the continuity of life and love beyond the tomb, and the deep sense of poverty of celestial compromises to satisfy the mourner on either side of the gulf that Death had set between” (E. Wood, 302) Rossetti’s painting romanticizes the joys of an earthly existence, but simultaneously suggests the possibility of happiness in the afterlife. The deeply spiritual, implicitly religious Blessed Damozel represents the medievalist continuity between Rossetti’s earlier and later work. Morris’s stained glass Musical Angel (3) mirrors Rossetti’s commitment to decorative aestheticism and the preservation of the subject’s romantic soul.

In the particularly medieval medium of stained glass, Morris designed a series of pieces for the St. James’s Church in Stavely, Cumbria. Within the highly spiritual context of the church, Morris’ Musical Angel induces the hope of a beauteous existence in life after death. Standing on a interweaving layers of clouds, the angel holds her harp upright as if about to play. Her sideways gaze resembles that of Rossetti’s protagonist in his Blessed Damozel. A brilliant magenta halo surrounds the angel’s head, which provides a sharp contrast with the dark mosaic-like patches of blue that comprise the background. Particularly evident in the angel’s robe and the star-studded sky, Morris’s intricate design work transports the viewer to the most ideal of locations: heaven. While embodying the romanticized medievalism of Rossetti’s painting, Morris’s Musical Angel (3) leans more toward the ornamental style of the Aesthetic Movement. Correspondingly, Burne-Jones’s stained glass St. Catherine with two angels and related scenes utilizes the “simple lines, clear forms and bright but restricted color” of Morris’s design (Whiteley, 62). In his 1880 The Golden Stairs, Burne-Jones allows the order of design to dominate his composition.

In the particularly medieval medium of stained glass, Morris designed a series of pieces for the St. James’s Church in Stavely, Cumbria. Within the highly spiritual context of the church, Morris’ Musical Angel induces the hope of a beauteous existence in life after death. Standing on a interweaving layers of clouds, the angel holds her harp upright as if about to play. Her sideways gaze resembles that of Rossetti’s protagonist in his Blessed Damozel. A brilliant magenta halo surrounds the angel’s head, which provides a sharp contrast with the dark mosaic-like patches of blue that comprise the background. Particularly evident in the angel’s robe and the star-studded sky, Morris’s intricate design work transports the viewer to the most ideal of locations: heaven. While embodying the romanticized medievalism of Rossetti’s painting, Morris’s Musical Angel (3) leans more toward the ornamental style of the Aesthetic Movement. Correspondingly, Burne-Jones’s stained glass St. Catherine with two angels and related scenes utilizes the “simple lines, clear forms and bright but restricted color” of Morris’s design (Whiteley, 62). In his 1880 The Golden Stairs, Burne-Jones allows the order of design to dominate his composition.

By the 1880s, Burne-Jones stylistically distinguished himself from Rossetti. Derivative of no particular literary source, The Golden Stairs represents “no particular legend, [nor does it contain a] particular symbolic meaning, but like music, captivate the senses, and transport the beholder into a realm of piece and beauty” (De Lisle, 122). Descending a curved golden staircase, a group of exquisite women without the slightest imperfection make their way to a door. Through the opening in the entranceway, one notices shimmering columns of gold. The woman about to enter the hall gives the viewer a slight smile, as if to express the magnificence to behold within the building. Each woman carries an instrument. Once inside, they will perhaps join together in heavenly music and song. Burne-Jones replaces pictorial narration with a “formal and classical [style], concentrating more on line, color and overall design” (C. Wood, 121). Each individual component is organized and united within a larger decorative structure. Dressed in blue tinted robes, the women stride down the golden staircase. This striking duality leads the viewer’s eyes down the top of the curved staircase to the bottom; it also creates a semi-circle frame around the entranceway. What is more, the highly textured robes of the figures contribute to the painting’s concern for decoration. Moreover, Burne-Jones’ The Golden Stairs concerns itself primary with aesthetic beauty. This in itself, however, represents “a beautiful romantic dream of something that never was, never will be- in light better than any light ever shone- in land no one can define or remember, only desire- and the forms divinely beautiful” (Barne, 98). In his transition to a highly formalized style, Burne-Jones still maintains the Pre-Raphaelite concern for romantic imagery indicative of spiritual transcendence.

The intimate association of Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti initiated the second generation of Pre-Raphaelitism, which aimed to express spiritual truths through aesthetic beauty. The Aesthetic Movement and the popularity of its decorative style played an integral role in the pictorial evolution of their respective canvases; they allowed formal design to predominate and structure compositional space. From the 1860s onwards, Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti integrated their artworks with ornamental design and the romantic medievalism characteristic of the PRB’s legacy. They implemented design “in imaginative terms . . . in which the relationships between objects and persons, persons and patterned surfaces, pattern and color, were establishedÉto induce atmosphere and emotional response” (Watkinson, 193). Increasingly formal in their aestheticism, Morris, Burne-Jones, and Rossetti preserved the spirit of the PRB in their idealization of the medieval. While accommodating the contemporary taste for decorative design, the second generation Pre-Raphaelites employed medievalism as symbol of their commitment to the spirit of the PRB’s spiritualistic idealism.

Works Cited

Baldry, A. Lys. Burne-Jones. London: T.C. & E.C. Jack, 1910.

Barne, Rachel. The Pre-Raphaelites and their World. London: Tate Gallery Publishing Ltd., 1998.

Bell, Malcom. Sir Edward Burne-Jones A Record and Review. London: George Bell & Sons, 1899.

De Lisle, Fortunee. Burne-Jones. London: Methuen & Co., 1904.

Fitzgerald, Penelope. Edward Burne — Jones A Biography. London: Michael Joseph Ltd., 1975.

Mander, Rosalie. “Rossetti and the Oxford Murals, 1857.” Ed. Leslie Parris Pre-Raphaelite Papers. Ed. Leslie Parris. London: Tate Gallery Publications, 1984.

Treuherz, Julian. Pre-Raphaelite Paintings from the Manchester City Art Gallery. London: Lund Humphries, 1980.

Watkinson, Raymond. Pre-Raphaelite Art and Design. London: Studio Vista Ltd, 1970.

Wood, Christopher. The Pre-Raphaelites. London: Seven Dials, 1981.

Wood, Esther. Dante Rossetti and The Pre-Raphaelite Movement. New York: Cooper Square Publishers Inc., 1973.

Whiteley, Jon. Oxford and the Pre-Raphaelites. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, 1989.

Last modified 22 November 2006