f course, Leighton employed many models. Others recorded in the diary for 1893 were Dolly Hart and Lily Pettigrew. Neither women are identifiable in his pictures. They were employed for figure studies, composite heads and completing works already underway. But Mary was one whom he could recommend to artist friends and followers who were eager to take his lead and paint a striking, new face. They would have seen the pictures for which she sat when they visited Leighton's studio and on the walls of the Royal Academy. These artists would also recommend her to each other. Mary would go on to work for Anna and Lawrence Alma Tadema, Thomas Brock, Frank Dicksee, Herbert Draper, Princess Louise, Ralph Peacock, Charles Perugini, William Blake Richmond, Herbert Schmalz, Frederic Shields and John William Waterhouse. Mary's various addresses in St John's Wood and Kensington gave her easy access to the studios of the artists with whom she collaborated.

Millais

Mary's most important introduction was to John Everett Millais, an introduction that must have come from Leighton as a long standing, close friend and the only artist of equal prominence in the British art world. Millais lived in a grand studio house in Palace Gate, not far from Leighton. In his youth, a founding member of the revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, Millais, with a wife and eight children to support, had become incredibly successful and wealthy painting society portraits and sentimental pictures of young children. Now, aged 64, and in failing health, he hankered after painting more personally meaningful subjects and and Mary proved to be worthy inspiration for his ambition.

In the autumn of each year, after the Academy exhibition and as respite from the frenzy of the London art world, Millais was in the habit of visiting his in-laws at Bowerswell, near Perth in Scotland. Though suffering from influenza and rheumatism and a troublesome throat, whilst there in 1893, Millais began major pictures which had long been on his mind. He worked on the landscape background for a picture of the first Christian martyr, St Stephen (Tate Britain). Discussing the saint with a local Minister, they concluded that Stephen was only a youth at the time of his death. Millais used the brother of a son-in-law as the model for the slight figure of the saint, leaving the painting of the head until he returned to London the following spring when he could engage a professional - Mary Lloyd. The finished figure, lying on the ground, mouth slightly open, as if asleep, has a notably androgynous appearance. Having completed the picture, Millais immediately set to work on A Disciple (Tate Britain), another early Christian subject. There is now a sense of urgency as he hurried to commit these subjects to canvas while he was still able to do so. Following her success as St Stephen, Mary was again his chosen model. She is shown seated, facing right, clothed in a simple, enveloping black shift, her hands folded in her lap, her trusting, seeking face lifted upwards towards some unseen goal or presence.

Two paintings by John Everett Millais. Left: St Stephen (1895). Right: A Disciple (1895). [Click on all the images for more information about them, and to see larger versions.]

Millais considered these two paintings, St Stephen and A Disciple, among the best things he had ever done and was "very pleased" when the Tate Gallery bought both pictures whilst still on the easel. Millais then left London due to his ill-health, with the result that the pictures were not ready for the Academy for 1894 and he showed nothing.

The Academy, 1894

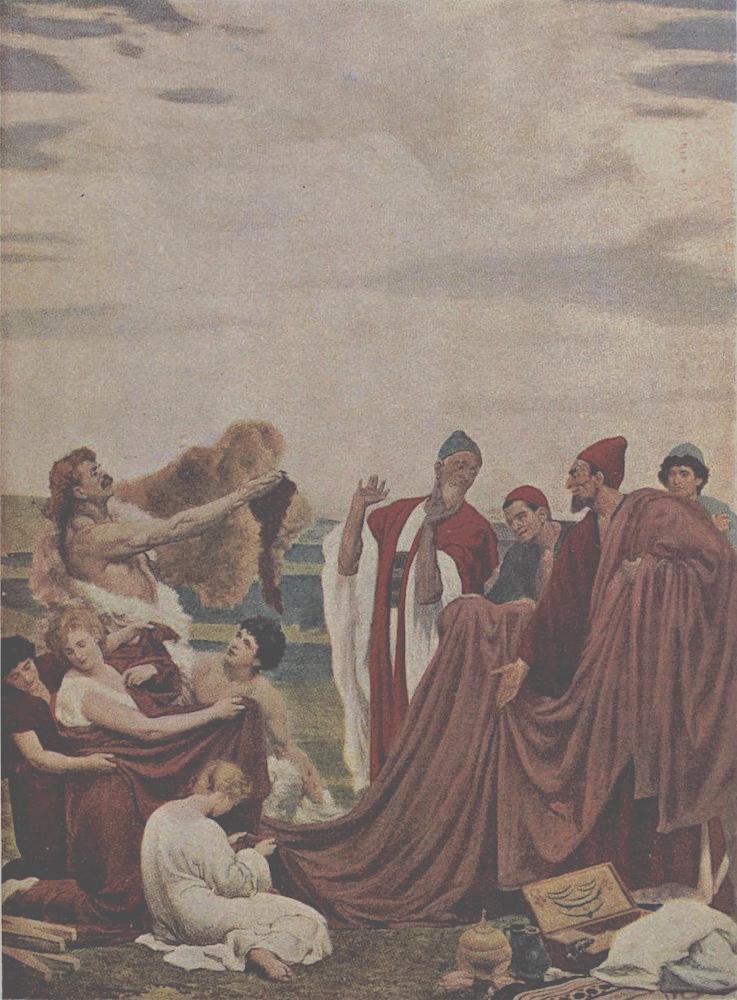

The Royal Exchange Mural, Phoenicians Bartering with Ancient Britons (1894).

Nor did Leighton show any picture identifiable as Mary in 1894. However, during that year, she was sitting for one of the female figures in the spirit fresco, the Phoenicians Bartering with Ancient Britons, Leighton's contribution to a great cycle of scenes relating to trade and commerce, painted for the Royal Exchange in the City of London for the cost of the materials. Mary kept a magazine illustration of the work, along with others in which she is the sole model, amongst her memorabilia.

Mary did feature in Frank Dicksee's 1894 Academy picture, The Magic Crystal (Lady Lever Art Gallery). Dicksee had trained at the Royal Academy Schools and was a follower of Leighton. He lived and worked at 80 Peel Street on Campden Hill, close to his teacher. The two artists would often breakfast together and discuss their work in Leighton's leafy garden. In The Magic Crystal, Dicksee gives full rein to his fascination with elaborate colour schemes and textures.

Frank Dicksee's In The Magic Crystal (1894).

The picture was inspired by a distinctive gown worn by Lady Jean Palmer, a beautiful, wealthy society hostess whose cultivated gatherings the handsome bachelor, Dicksee, attended. Lady Jean's husband's money had come from the Huntley and Palmer biscuit business. The garment consisted of a transparent peacock-coloured dress over a pink under-dress. The heavily sequined sleeves, girdle and yolk were of the same shade of pink. After Dicksee admired the garment, Lady Palmer had it sent to him. Mary was painted life-size, wearing the gown and strings of large amber beads, seated on a throne-like chair, surrounded by rich fabrics. As a glamorous femme fatale, of no recognisable time and place, she gazes into a crystal ball.

Dicksee's sister, Margaret, also an artist and an exhibitor at the Royal Academy, was a campaigning suffragist, though he himself did not support the cause. Red lipstick was often worn by independent women at this time to indicate their flouting of social convention which regarded make-up as vulgar and "racy." Dicksee depicting his confident sorceress seemingly lipsticked may reference this trend. The exoticism of the picture attracted attention and it was described by the Saturday Review as "sumptuous and slightly artificial." However, the Palmers loved it and bought the work for their Berkshire home. When Dicksee decorated a leaf of an ivory fan for Lady Palmer the following year, he repeated Mary's head from The Magic Crystal. And Alma Tadema selected the picture when asked to suggest prints for a series entitled "The Most Beautiful Women in Art."

Millais made his accustomed visit to Scotland in the autumn of 1894 and began work on his final, large-scale narrative picture, Speak! Speak! (Tate Britain), inspired by his long-standing interest in the supernatural. Unusually for Millais, this was a classical subject which had been on his mind for forty years. The story is that of the deceased Roman bride who appears to her husband at dawn as he reads her letters by lamp light. The setting was the shadowy interior of medieval Murthly Castle in Perthshire, on the estate that Millais had rented for hunting and fishing. The bride parts the curtains of a four-poster bed, arrayed in all her shimmering finery, her arms, throat and waist encircled with sparkling diamonds, a tiara on her head. The astonished husband in Speak! Speak! and the viewer, are both left wondering whether the woman has really come back from the dead or whether she is a ghostly apparition. Millais intended the ambiguity, saying he did not know himself whether the woman was real or an illusion and nor did the husband!

Millais' "Speak! Speak" (1895).

The outfit worn by Mary as the bride was most likely devised by Millais' wife, Effie, who regularly supervised the dressing of the models for her husband's subject pictures, though, by this stage, Effie may have needed assistance as her sight was failing. Whilst the figure of the woman was painted from two young Scottish women, Millais again waited for his return to London early in 1895 to paint the face from Mary Lloyd. The model for the figure of the husband was a London-based Italian, Antonio Corsi, chosen for his fine throat. This would not be the last time Mary and Corsi would find themselves posing for the same work.

Millais now painted "like fury" to be ready for the Academy that summer: his son later recorded that never "had I seen him so well pleased with any work of his own" (Millais 307). And when the Academy bought the picture for £2000 under the Chantrey Bequest, "he was quite wild with delight at this marked appreciation of his brother artists" (Millais 307). As President of the Academy, Leighton would have had an incisive say in the acquisition of the picture for the Chantrey Bequest. He wrote to Millais expressing his "warm satisfaction at the purchase of your beautiful and impressive picture" (qtd. in Millais II: 316).

Leighton's health had never been robust. Arriving at the Athenaeum Club after a "Pop" concert at St. James' Hall on 29 October 1894, he suffered a first painful attack of angina. He was 63. His doctors and friends begged him to reduce his punishing round of commitments - "But that would not be life to me! I must go on. . . ." (qtd. in Barrington 318). Though Leighton's condition worsened through the winter, his concern was to fulfil his Presidential responsibilities and to complete a half dozen pictures for the upcoming Academy exhibition of summer 1895. Mary Lloyd was to play an important role in the creation of these works. For what would be his final, complete submission to the Academy, she posed for two sombre pictures - Lachrymae (Metropolitan Museum of Art), and 'Twixt Hope and Fear (private collection).

Lachrymae shows Mary as a statuesque, grieving woman, robed in black, her head bowed, leaning an arm on a Doric column for support. Atop the column is a funerary urn, at its base an emptied libation bowl and a hero's discarded wreath. Withered leaves give a feel of autumnal decay and a brilliant burst of light behind the cypress trees in the gathering darkness indicates the setting sun and the dying of the day.

Three more of Leighton's paintings of 1894-95. Left to right: (a) Lachrymae. (b) 'Twixt Hope and Fear. (c) Flaming June.

For 'Twixt Hope and Fear, Mary, swathed in heavy, brown draperies, sits sideways on a Greek klismos chair, her sculptural arm dangling over the chair back, which is covered with the skin of a sacrificial ram. She turns to face the front, her expression registering conflicting emotions as she awaits some expected news. The undifferentiated gloom of the background veils her eyes. Neither of these pictures refer to identifiable characters or narratives and are concerned rather with mood and atmosphere. Leighton's collection of ancient Greek-style studio props, such as the furniture, the instrument, vessels and fabrics, were put to good use in these pictures.

An antidote to these two sombre pictures, Leighton's third work for 1895 with which Mary can be connected, is Flaming June (Museo de Arte de Ponce, Puerto Rico). A coiled, somnolent figure of a woman, inspired by Michelangelo's sculpture, Night, in the Medici Chapel in Florence, is shown swathed in glowing, diaphanous orange draperies. She lies on a marble bench in a sultry Mediterranean setting, the blaze of the noonday sun reflected off the sea behind her. A circular form on a square canvas. The undraped figure studies for the picture had been executed earlier in the 1890s and Dorothy Dene is identifiable in a head study. However, by the time Leighton was in the final stage of painting, the art historian Martin Postle is of the opinion that the model was Mary Lloyd, based on comparison with a photograph of her profile in later life. This suggestion is corroborated by Leighton's letter to Mary of 10 January 1895, a few weeks before the picture was completed. The letter explains that he will need her for an extra day to complete the "head and hand for your picture," as long as this did not mean "throwing over" anyone else. Note, he states "hand," in the singular. Flaming June is the only picture he was working on at that time to feature a figure with only a single hand showing. Leighton also added a PS to the letter to let her know that Millais had come back, presumably so that she could expect to be hearing from him for the final stages of his own 1895 pictures.

At this time of year, Mary would have been posing in Leighton's Winter Studio. This glass house allowed in maximum light during the dull British winter, but it must have been freezing for both artist and model, even though heated. Having entered Leighton's house through the door reserved for models, at street level on the side of the building, Mary would have accessed the studios via the backstairs.

Lachrymae and Flaming June were displayed on easels for Leighton's final Spring Concert in March 1895. Along with 'Twixt Hope and Fear, they were part of the group of six shown to Leighton's friends, the Prince and Princess of Wales and their two daughters, when the royals came for a private viewing on 29 March. The group was photographed by Bedford Lemere on 1 April and was in position for Show Sunday on 7 April, the open studios held by artists the day before the sending in of pictures to the Academy. Once the works had been dispatched, Leighton left immediately for North Africa on his doctors' orders to try and regain his health. As this was before the opening of the Academy exhibition, he had entrusted Millais with delivering the Presidential address at the Academy Banquet on 4 May. Millais did his best to deputise for his old friend and all present commended his fine speech, but his throat problems meant he was struggling and barely audible.

Links to Other Parts

- Part I: The First Sittings; the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1893

- Part III: Mary and the Royal Academy Exhibition of 1895

- Part IV: After Leighton and Millais: 1896

- Part V: Later Appearances; the Final Years; Bibliography

Created 25 September 2024