This review originally appeared on H-Net (Humanities and Social Sciences Online), and has been adapted and reformatted for our website, and illustrated, by Jacqueline Banerjee. [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source and (2) link your document to this URL or credit the Victorian Web in a print one. Click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information where available.]

Introduction

Ophelia, by John Everett Millais (1851).

Past visitors to the Tate Gallery, as it was then known, will be familiar with the archetypal Millais which seems to be on permanent display, Ophelia, "the most popular painting at Tate Britain." Indeed, such is the association between Millais, Ophelia and the Tate that this painting provides the cover photograph for the useful booklet given to visitors, for the Press pack and also for the accompanying catalogue — besides forming the background to the Exhibition poster. Naturally, there is more to Sir John Everett Millais (1829-1896) than Ophelia (1851), and Tate Britain has organized a long-awaited retrospective, the first since 1967 (at the Royal Academy) and, the Press release indicates, "the first exhibition since 1898 to examine the entirety of the artist's career" — notably because it includes a large group of his late Scottish landscapes. It is naturally impossible to discuss here all the 140 paintings and works on paper which are featured, but the exemplary website pages devoted to the Exhibition give illustrations of all the major works displayed, with excellent explanatory notes.

Millais and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood

Left: Christ in the House of His Parents (1849-50). Right: Lorenzo and Isabella, or just Isabella (1848-49).

Not unexpectedly, the first room concentrates on Pre-Raphaelitism, since the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was founded in John Millais's parents' house in 1848. Among the other future celebrities present were William Holman Hunt and Dante Gabriel Rossetti. If Pre-Raphaelitism can best be described in opposition to Academicism or, as the Minneapolis Institute of Arts defines it on its website, a "style which advocated a return to serious subjects and naturalistic representation, and emphasized accuracy of detail and color", then the precocious work of Millais did not adumbrate his future Pre-Raphaelite militancy. The Exhibition has a magnificently Academic Pizarro seizing the Inca of Peru (1846 — admittedly painted when he was only sixteen). Technically, the first painting to be explicitly presented in the context of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood was Isabella (1848–9). Together with Christ in the House of His Parents (The Carpenter's Shop) (1849-50), these paintings established Millais's reputation as a provocateur, the former because of its overt rejection of Academicism, the latter for reasons which ring all sorts of familiar bells today. The more bigoted Protestants saw the scene as having inacceptable Roman Catholic tendencies and the general religiosity of the time was averse to realistic depiction of Jesus Christ. With The Eve of St Agnes (1850) and Mariana (1850-1), Millais deliberately infringed the conventions of the time by associating erotic desire with "respectable women." The superb contemporary portraits shown (Portrait of a Gentleman and his Grandchild (James Wyatt and his Granddaughter, Mary Wyatt), 1849; Mrs James Wyatt Jr and her Daughter Sarah, 1850; Thomas Combe, 1850) apparently did little to compensate for the scandalous nature of his other works — and yet, paradoxically, the Royal Academy never refused to exhibit them.

Millais: "Romance and Modern Genre"

Left: The Black Brunswicker (1860). Right: The Blind Girl (1856).

Room 2, on "Romance and Modern Genre" is largely devoted to his next field of exploration, that of figure painting with a historical dimension, often depicting the conflict between love and patriotic or religious duty. We thus have A Huguenot, on St. Bartholomew's Day, refusing to shield himself from Danger by wearing the Roman Catholic Badge (1851-2, on the massacre of French Protestants by Roman Catholic mobs on 24 August 1572); The Order of Release, 1746 (1852-3, on the last Jacobite Rebellion); The Proscribed Royalist, 1651 (1852-3, on the English Civil War); Peace Concluded, 1856 (1856, on the ending of the Crimean War); The Escape of a Heretic, 1559 (1857, on the Spanish Holy Inquisition); and The Black Brunswicker (1859-60, on the Battle of Waterloo). Only six years separate The Order of Release, 1746 from Pizarro seizing the Inca of Peru, and yet these two "historical scenes" are light-years apart — or so they appear to be to the non-specialist of the Pre-Raphaelite movement. Room 2 also contains the well known picture of The Blind Girl (1854-6), in all its glorious colour (the girl's red hair!), impossible to render even with the best modern techniques of reproduction.

Millais and Aestheticism

Left: Spring (1856-9). Right: The Vale of Rest (Where the weary find repose) (1858).

Aestheticism. The curators (Alison Smith, Curator at Tate Britain, and Jason Rosenfeld, Associate Professor at Marymount Manhattan College, New York) explain their choice of this term in a very convincing wall text. Millais's evolution is perfectly encapsulated in the difference which one perceives between Spring (1856-9), with its arguably archetypal characteristics of Pre-Raphaelitism, and The Vale of Rest (Where the weary find repose) (1858). We are therefore not surprised to see the continuation of this evolution towards "The Grand Tradition" in the next room, with classical Biblical subjects (and also with a tendency to classical treatment?) like Esther (1863-5) or Jephthah (1867). Fortunately, the curators provide their modern de-Christianised visitors with the essential information on these Old Testament subjects — but few members of the public seemed to be interested. In contrast, the two assassinated sons of Edward IV in The Princes in the Tower (1878) continue to speak to the crowds (it was hardly possible to approach some of the pictures, let alone the captions, when I was there — this is of course the ambivalent ransom of success for all museum authorities). The patriotic scenes, The Boyhood of Raleigh (1869-70) and The North-West Passage (1874), do not arouse the same enthusiasm as when they were first exhibited. We must bear the Imperial context in mind: Victoria was proclaimed Empress of India in 1877 as the culmination of Disraeli's efforts to revive interest in the Empire, largely neglected by his Liberal rivals. Few visitors today will look at these pictures with the Imperial pride which they both assumed and enhanced. That the former young rebels of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood now appeared as supporters of the Conservative Imperial dream was of course highly ironical.

Millais' Fancy Pictures

Bubbles (1865-66).

As a total contrast to his "Imperialist" pictures, Millais produced the "Fancy Pictures" of Room 5. A wall text conveniently explains what the phrase means in art history: "The 'fancy picture' first came into existence during the eighteenth century and can be described as genre painting where the sentiment takes precedence over evolved narrative." The archetypal work in this category is the celebrated Bubbles (1866). The original was not often seen until recently, but it is now on long loan to the Lady Lever Art Gallery, whose website usefully retraces the history of the painting, indirectly explaining why Millais was blamed for his commercialism (one more inexcusable sin for the idealists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood of his young days):

Bubbles will be forever linked with washing and cleanliness because it was used to advertise Pears' soap. Owner of the painting Unilever has granted the Lady Lever a long-term loan. In many people's minds the painting is also associated with the song "I'm Forever Blowing Bubbles," anthem of Cup Finalists West Ham FC since the 1920s when the song was a hit. Painted by Pre-Raphaelite artist Sir John Everett Millais in 1886 and his best-known work, Bubbles was originally called A Child's World. It shows the artist's grandson William James dressed in a Little Lord Fauntleroy-style velvet costume with a ruffled collar. The painting was bought by A. and F. Pears and the managing director, Thomas Barrett, turned it into an advertisement by adding a bar of soap in the foreground. It was a brilliant masterstroke and the painting is today still associated with the product. Lever Brothers acquired A & F Pears in 1914 and subsequently the company became part of the Unilever Group. Pears was retained as a separate brand and Unilever kept Bubbles at its global headquarters on the banks of the Thames.

Millais' Portraits

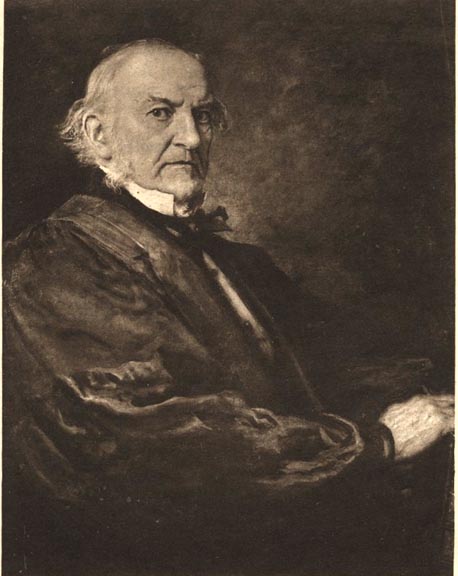

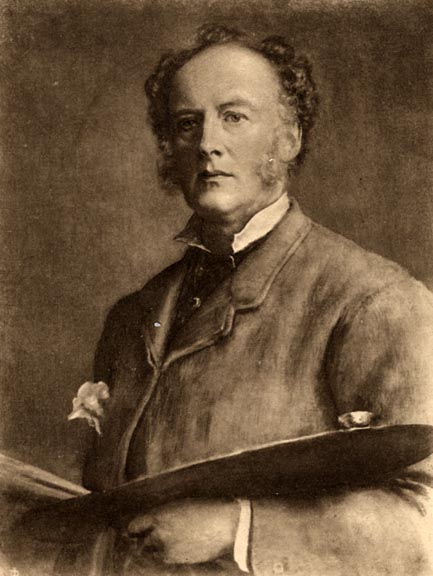

Left: The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone, MP (1885). Right: Portrait of the Painter (1880).

Entering the impressively large Room 6, one is immediately fascinated by the reconstruction of Millais's studio, including the actual 18th century armchair used by his wealthy sitters and his large studio easel (his palette, brushes and oils are also on display). This is the room devoted to the "Portraits" which made him a very rich man — and one understands why when one sees that it features two Prime Ministers (The Right Hon. W. E. Gladstone, MP, 1878-9 and Benjamin Disraeli, The Earl of Beaconsfield, KG, 1881); a banker's daughter and marchioness (The Marchioness of Huntly, 1870); a banker's wife (Mrs. Bischoffsheim, 1872-3); a fashionable actor (Henry Irving, Esq, 1883); a future successful actress (A Jersey Lily [Lillie Langtry]; 1877-8) and two famous authors (Thomas Carlyle, 1877, and Alfred Tennyson, 1881) besides his self-portrait (Portrait of the Painter, 1880, commissioned by the Galleria degli Uffizi, Florence, to be hung in its Collezione degli Autoritratti next to Velázquez, Bernini and Dürer) and those of his wife and some of his children.

Millais' Late Landscapes

Dew-drenched Furze (1890): one of Millais's remarkable late Highland landscapes.

Few people must have seen the originals of the twelve paintings of the Highlands of Perthshire which form the theme of the final room, "The Late Landscapes," because they are widely dispersed. If Scotch Firs: "The silence that is in the lonely woods" (1873, a quotation from Wordsworth) arguably reminds the viewer of Millais's Pre-Raphaelite manner, the caption of "Blow, blow, thou winter wind" (1892, a quotation from As You Like It) informs us that it is "one of the artist's rare paintings dealing with contemporary social ills" (a man abandoning his family). And when the caption of the stupendously gorgeous large painting, The Sound of Many Waters (1876) tells us that "in this mature work he effectively conveyed the features of volcanic rock without the meticulousness of Pre-Raphaelitism," we wonder what the result would have been if he had displayed "the meticulousness of Pre-Raphaelitism." The free visitor's booklet [had] a map of the locations (near the River Tay) where these landscapes were painted — an excellent idea.

References

"Artwork Highlights — Bubbles by Sir John Everett Millais." National Museums Liverpool. Web. 6 April 2014. [Note: this entry differs somewhat from the one quoted above.]

Millais: Tate Britain: Exhibition. Web. 6 April 2014.

Rosenfeld, Jason and Alison Smith. Millais. London : Tate, 2007. 272 pp. ISBN: 1854376675 (pbk.); 1854377469 (hbk.) (exhibition catalogue, shown right).

Last modified 15 April 2014