The following excerpts come from Chapter V and were selected by Shirley Nicholson, who also introduces them. They have been formatted, linked and illustrated from our own website by Jacqueline Banerjee. Click on all the images to enlarge them, and for more information about them. Page numbers are given in square brackets, as are the two brief interpolations in the text.

Jane Ellen Panton was born in 1848 (some records say 1847) the third child and second daughter of the successful artist William Powell Frith. She was always known as Cissie by her family and friends and married James Panton in 1869. In 1908 she published an autobiography, Leaves from a life containing delightful reminiscences of her position near the top of a large Victorian family (twelve children, of whom ten survived beyond infancy). This book forms an important addition to her father’s three volume autobiography. Cissie writes about John Everett Millais and Lord Leighton, and a lot too about the literary figures - Dickens, Thackeray - she knew well. But the excerpts here are selected from Chapter V, entitled "More especially our set," and gives insights into her father's more intimate circle of friends, some of whom were members of the early Victorian Clique. — Shirley Nicholson

rtists in our day were divided into sets, much more, I fancy, than they are now. There was our set, centred in the Kensington and Bayswater districts; there was the St. John's Wood set; and there was another set which comprised Millais, Leighton, Sir Francis Grant, and some of the more aristocratic members of the Academy. Yet I may say that we were intimate more or less with the members of all. I can just recollect the presidency of Sir Charles Eastlake, but I do not remember him personally, and I fancy that at that particular time Papa was out of favour in high places, and we were more or less under a cloud, that would touch his social relations, but that certainly never was felt by us as children and young people at all.

Sir Francis Grant was an extremely courtly and delightful gentleman, always scrupulously polite when we met him out, but we never went to his house, and nourished a hidden hatred of his daughter, because she was the President's daughter, older much than we were, and apparently [87/88] able to go anywhere and do anything she chose. I can just recollect her, and that is all; but Sir Francis I remember perfectly because he was so nice to look at, and because he always, in some miraculous way, recollected our names and all about us when we met him. The first artist I recollect was Turner, who, as I have mentioned before, died when I was three; the second was Mulready. He lived in what was then "Linden Grove," and is now Linden Gardens, a turning out of the Bayswater Road, which in those days was an ideal spot, as it was quite out of the way of all traffic, and each small house had its really nice garden. In Linden Grove lived not only Mulready, but Creswick, Mr. and Mrs. Gray, the father and mother of Edward Ker Gray, and Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Wigan, from whose hospitable house Irving was married; and as we knew them one and all Linden Grove was, of course, peopled with friends.

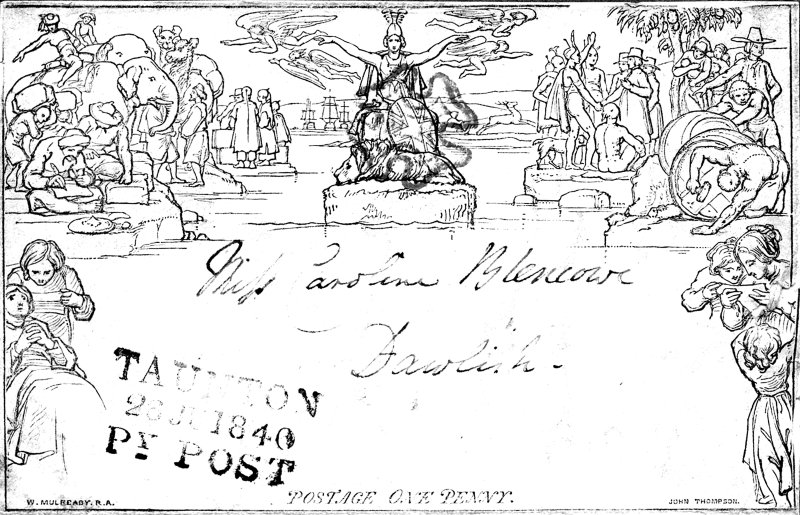

I remember Mulready as a small, very neat man, very deaf, and very kind, and for years I treasured the black and blue "Mulready envelopes" he gave me, which were the predecessors of the penny stamp, and he never could understand why they were superseded. The design was certainly very good, but as the letter had to be written on the paper, which was one with the envelope, the method was clumsy, and the penny stamp placed on any envelope, which could hold either a large or small sheet of paper as required, was much to be preferred. But I gathered from Mr. Mulready that [88/89] he had some grievance against the Post Office for not using his envelopes, of which he appeared to have a great many surplus copies. I trust he knows now how valuable they are; I wanted a couple for a schoolboy friend nine or ten years ago, and I know I had to pay something like £4 for them.

A "Mulready envelope."

Mr. Mulready was very old, I think, when we used to go and see him, but one of the greatest difficulties I have in writing these remembrances is to get things into focus; when one is small every one else appears tall; and when one is young every one over thirty-five appears venerable; I fancy he could not really have been more than seventy at the outside, but he was very bent and feeble, and had had heavy domestic trials. What they were I never quite knew, but he lived quite alone in Linden Grove, and I know there were a wife and son at least somewhere or other in the world, with whom he had nothing to do. His hands shook very much when he gave me the "Mulready envelopes," and he said a good deal about the foolishness and the hideousness of the penny stamp; and I do not think he was painting still, for we never went into his painting-room. I know we were sorry when he died in 1863, so I know he must have been kind to us; but then every one was in those days, and whenever we went to any of Papa's friends' houses we were always made a great deal of, and allowed to do very much as we liked.

Mr. and Mrs. Creswick and Mr. Creswick's sister lived next door, or next door but one, to [89/90] Mulready, and often and often we went to see them there. Mrs. Creswick was a small and most sweet lady; Miss Creswick was severe, and kept her and us too in a species of order we very much disliked, while Mr. Creswick was most festive, rollicking and amusing, albeit he used more "swear-words" than would be considered orthodox nowadays, and was too fond both of food and drink to be always in the best of health. He was extremely well off in the later years of his Ufe, and he turned the Linden Grove house into a small palace; he also had a most charming garden and painting-room. He had no children of his own, but he used to have big parties for us and other young folk when we used to dance in his painting-room and the drawing-room, which were connected, and have supper: and such a supper! in the dining-room and conservatory, which was all lighted up for the occasion.

Linden Grove itself in those days was not lighted, one turned out of the Bayswater Road into what appeared to be a dark tunnel, and I well recollect an amusing episode, due to this fact, that Mr. Creswick was never tired of telling us. The Athenaeum Club in those days used to be a very favourite rendezvous for many of the Royal Academicians, and several of them and their friends met there between 4.30 and 7 to play whist day after day, Mr. Creswick among the number. He was very fond of new copper coins, which he saved for us, and on this especial occasion some one had [90/91]presented him with two very new and very bright farthings, which he placed in his waistcoat-pocket, and gave no second thought to until he reached home and had just, as he thought, given the cabman his fare of two shillings. In a moment he recollected the farthings, and he called to the man to stop ; but, glancing at the bright and shining coins in his hand, by the sparse light afforded by the oil lamps in the cab, he drove off at the top of his speed and disappeared into the Bayswater Road. We were disappointed of our new farthings, but I wonder what the cabman thought — I do not want to know what he said — when he realised the real worth of the coins he had made off with. The two sovereigns he fondly hoped were his were brass, and he was even minus the two-shilling fare that he had really earned.

The Athenaeum Club today.

One Sunday we went ta see Mr. Creswick, who was laid up on the sofa with one of his usual attacks: I think they must have been caused by gout, for they made him extremely irritable : gentle Mrs. Creswick used to look smaller than ever when he was suffering, while even his redoubtable sister was not quite as militant as usual: and when we went in to see him we were warned to be careful, as "Tom" was not very well. We trailed in after Papa as meek as several mice, to be met with a volley of curses; not addressed to us, however, but to some one unknown; alas! not to remain unknown for long. It was just at the time when Silas Marner had come out, and every one was reading that [91/92] most exquisite book. Papa had had it from Mudie, and I had read it aloud to him while he worked. He had been tantalised himself by the mystery of the disappearance of Dunstan, but I would not allow him to look at the end; and when we had finished the book he snatched it up, and saying, "Well, no one who has this copy shall wait as long as I have done to know what happened to that fellow," he wrote at the bottom of an early page just what had occurred. By some extraordinary and evil chance this very copy had reached Mr. Creswick, who adored mysteries, and read as many novels as any love-sick miss, and I can remember distinctly the sudden pause in his curses, and the curious white look which came over his face, when Papa told him he was the culprit. He did not speak for a few moments; I really don't think he could; afterwards he confessed his first impulse was to burn the book and turn us all out neck and crop; but Silas Marner, which one can buy now for a shilling, or even less, was then a two-volume business, and I think meant a guinea; and Papa was one of his dearest friends, and they were both Yorkshiremen, while he simply adored us en masse; so Papa was forgiven, albeit we were solemnly warned never to mention Silas Marner again before him, and I am quite sure we never did.

The last time I saw Mr. Creswick was the day before I was married, when I went to say good-bye and to thank him for a most exquisite landscape he gave me as a wedding gift. He died while we were on [92/93] our honeymoon, and I never entered that hospitable house again. He declared his life had been shortened by the passing of the underground railway beneath his house and garden, and that he would have to leave the charming place; one could, aided by a strong imagination, fancy one felt a slight vibration in the painting-room. Well! he was spared the real shakings and vibrations of the present day, which would, I am sure, have driven him really out of his senses; and his house and garden are now either flats or subdivided into much smaller premises.

The first artist I really adored and worshipped was Sir Edwin Landseer; I think I must have been about nine years old when I made his acquaintance. Mamma had one of the tremendous "parties" which used to punctuate our childhood and girlhood, and as he was coming I begged hard to be allowed to sit up. At last the party was in full swing, and I sidled up to Papa. I was in a very, very stiff white frock, trimmed with a great many of Miss Wright's "cart-wheel" embroideries, and a broad scarlet sash was gaily tied round my waist. The bodice had short, full-puffed sleeves, and in each puff was a rosette of very narrow scarlet velvet, these rosettes being put in and taken out by Miss Wright when the frock went to be washed, and I felt very well dressed and very important. Papa pointed out the great man to me, and I was enraptured. He was small and compact, and wore a beautiful shirt [93/94] with a frill in which was placed a glittering diamond brooch or pin, I do not know which; and he looked to me like one of his own most good-humoured white poodles. He was curled and scented and exquisitely turned out, and I said at once: "Oh ! what a delightful old gentleman!" Papa meanly went across to Sir Edwin and told him what I had said. He spoke with a slight stutter or drawl. "I shall propooose," he said, and coming over to where I stood gazing in rapture at the embodiment of my dream, he at once, and to my vast confusion, proceeded to demand my hand from Papa. It took me some little time to realise that nine is not a marriageable age, but I do not think many small girls can recall with pride that at this early stage in their career they were asked formally in marriage by such a great celebrity, even though it was only in joke.... [94/95]

There was a romance in Sir Edwin's own life, but that has never been told; all I heard about was that there were reasons for silence, and that there were some beautiful girls who were very like him; but his end was sad; he ceased to paint, became imbecile, or childish, and was looked after and tenderly nursed by "Miss Jessie," his devoted sister, who had given up her life to save him from anything like domestic worries. When we used to go and see him he lived in a large house surrounded by a vast garden, where, as did Mr. Ansdell, he kept the animals he used to paint, and I more than once went with him to the "Zoo" when he made studies for the lions at the base of Nelson's Monument in Trafalgar Square. Nothing made me more savage than to hear these lions criticised and laughed at by ignoramuses; I know the lions are good, as well as I know the enormous amount of study Sir Edwin gave to them, and the vast trouble he took about the drawings he made from the great beasts themselves.... [96/100]

The lion on the south-east angle of the Nelson Column.

We possessed in those days an old friend, a banker, who invariably said the most polite things to one's face, and then, in absolute unconsciousness of the fact, spoke out his real opinion without a change of voice or even of intonation. On one of these occasions, after complimenting George Cruikshank profusely on the performance of the Ballad [The Loving Ballad of Lord Bateman, an 1871 adaptation of a traditional ballad, in which both Dickens and Cruikshank were involved], he looked first at Mrs. Cruikshank and then at George, and remarking aloud, "I don't know which is the greater fool," he walked away. Fortunately he had the reputation of being a little mad, and he died, poor man, years after in an asylum, but it required all Mrs. Cruikshank's belief in her husband and his doings to pass this over. "Of course, no one who was not insane could be so rude and untruthful," and the matter was not alluded to again. I retrieved my hat and feather, but I think Mrs. Cruikshank must have taken the episode to heart, for we never were regaled with the Ballad again, and I for one was grateful.

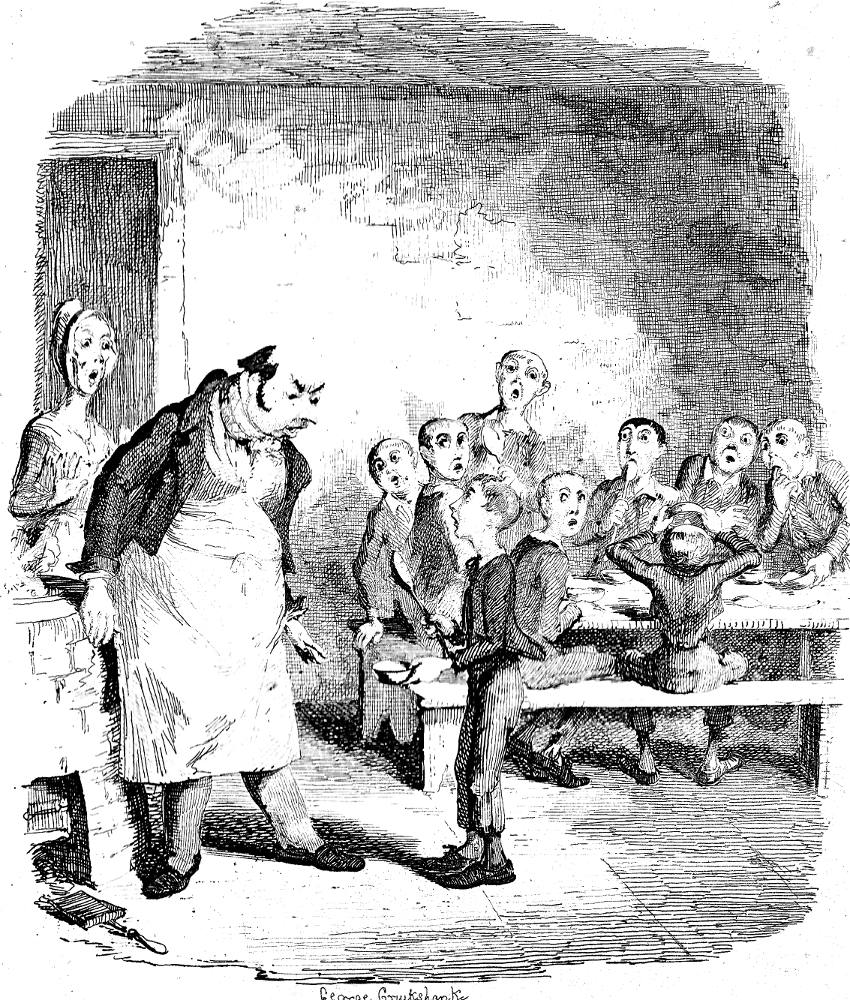

I do not think anyone ever existed who had greater belief in himself than had old George; I have myself heard him declare that he wrote Oliver Twist, and that Charles Dickens only spoiled the story [1OO/101] from the names upwards; and whenever he was present few of the other guests could get in a word edgeways into the talk. He believed he wrote the Lord Bateman ballad as well as illustrated it, which he most certainly did not, and in fact he was full of ideas of what he had done, and was perfectly certain that no one on this earth knew more or could do more in the walks of art and literature than he had done and meant to do.

Oliver asking for more, in Cruikshank's illustration for Oliver Twist.

I shall never forget what we suffered, too, from his horrible picture, The Worship of Bacchus. Papa was very particular about his wine, and in those days a charming German wine-grower used to come round at a certain time of the year and obtain orders for hock; we were not so pleased to see the wine which followed his visits, as we were to see the grower, who generally brought us sweets, and was always kind and nice to us; for we had to sit on the flight of steps leading to the kitchen and count the bottles as they were stowed away by our man- servant. We were employed in this task one day when Mr. Cruikshank called, and to this was due the fact that we were commanded to repair to his house, somewhere in the Regent's Park direction, to see his dreadful work. Papa was the most abstemious of men, and we are one and all teetotalers, not from any matter of principle, but simply because we do not like wine; and it was a double insult to us to be made to listen to the rabid abstainer while he described bit by bit the hideous picture he had spent years in painting. I have an idea he left it [101/102] to the nation; but I have never seen it since; still, we went so often that if it were necessary I could describe it perfectly from the start of the infant, at whose christening party most of the guests were hilariously drunk, while the mother was being given a foaming glass of porter by the old nurse, to the end, where a lugubriously black coffin was being carted to a pauper's grave on the shoulders of red-nosed men, with enormous hat-bands round their hats, this being the inevitable conclusion to the career of any one who indulged in anything stronger than water....

Cruikshank's painting, The Worship of Bacchus (1860-62).

As Mr. Cruikshank had not always been a teetotaler, I can only suppose he had forgotten the taste and smell of all spirituous liquors; he could not have been the blatant humbug [his] consumption of wine in cookery would otherwise make him out to be! I perfectly well recollect that when he first sat down to dinner he collected all his wine-glasses and placed them ostentatiously as far away from him as he could; and he finally gave up dining at our house, because I was going to marry a brewer, and [102/103] he really could not give his countenance to such an outrageous match. I believe his faithful and adoring wife was much put out of countenance at his death by the appearance of a second claimant to her place; but this may only be gossip; such a sternly virtuous individual as George Cruikshank could never have strayed so far from the right paths as to have had a second establishment, any more than he could have known how much intoxicating stuff he was consuming in my mother's most excellent cookery.

Mr. Henry O'Neil was, I think, one of our earliest and greatest friends, and I have sat to him more, perhaps, than to any other of our painter friends. My first appearance in his pictures is as a very small child in his once well-known picture, Eastward Ho!, the sailing of a troopship for the Crimea [Cissie's memory is at fault here: the destination was India]; and my last as one of the terrible young girls strewing primroses before the feet of the present Queen when she landed in England forty-four years ago to marry the King, when, attired in a much be-crinolined white muslin, a red cloak, and a species of mushroom hat, I sat for one of the real girls who had welcomed the Princess, the real ones not being available for some reason or other. The hideous and unsuitable costume for a bitterly cold March day had been selected by the Queen as being typically English; we were cold enough under the balcony of the Royal Academy (National Gallery), where, suitably clad, we waited for the cortège. I cannot [103/104]think what the girls in muslin must have felt like, for not even the red cloaks could have kept them even passably warm.

The Landing of HRH The Princess Alexandra at Gravesend, 7th March 1863.

About the year 1858, both Mr. John Phillip and Mr. O'Neil offered to paint my portrait, but as my eldest sister was offended at this, judicious hints from Mama persuaded Mr. O'Neil to paint her, while, I am thankful to say, Mr. Phillip painted me; for mine is by far the better picture of the two. It represents a small, dark- haired girl clad in a pink print frock ; the trim- ming is black velvet, and it is cut square at the throat and filled in with white lace, while over one shoulder a black silk mantle is gracefully disposed. That pink frock appeared again in front of the Railway Station picture, only lengthened and made more grown up; while the mantle, our governess's best Sunday garment, is worn by the lady in the Crossing Sweeper picture, and, moreover, was used in Claude Duval. All I recollect of Mr. O'Neil's picture is that a good deal of pale and washy blue enters into the composition, but then my sister, being fair, was always given blue, while pink and scarlet were my portion, because I was her exact opposite in colouring, as in every other single thing. I used to go with my sister to Mr. O'Neil's painting-room, and my great joy used to be allowed to stand behind him while he painted, brushing his longish white hair with the hearth-brush. I had a delightfully funny sketch done by him of this, and I only wonder the picture was not worse [104/105] than it undoubtedly is.

We had the most charming meals there, consisting, as far as I can recollect, of cake and strawberries: always strawberries, in great heaps; and when I sat to him as a model for odds and ends, the sittings were marked by presents, generally gloves in generous packets of dozens or half-dozens; indeed, I do not think, once I had begun to have an allowance, I ever bought myself gloves again, so good and generous were our artist friends to us! Mr. O'Neil never married; he fell desperately in love with one of my mother's bridesmaids, who even in her late middle life was beautiful to behold, but she was a Roman Catholic. My mother had an idea that Mr. O'Neil was "not steady"; anyhow, the engagement was never allowed. Mr. O'Neil lived silently and alone until he died, and the lovely bridesmaid made a wretched marriage, and must have thankfully lain down to die when the call came to her. The only fault I could find with Mr. O'Neil was that he always came on Sunday evenings, and invariably commanded us to play to him, and we always had to obey. But I was truly thankful when bed-time struck on the same clock which used to strike the hour for Papa to retire in his childhood, and we knew the piano was closed for our public performances until yet another Sunday came round.

We liked John Phillip: "Phillip of Spain," as he was always called: but at the same time I, for one, was afraid of him. He could never tolerate the least amount of movement, and I can see [105/106] now how he turned round on his wife with a snap and a snarl which nearly frightened her into fits because she would sit just behind him while he was painting, drawing her needle in and out of some very stiff material which creaked in the most horrible manner possible. I hated the noise, too, but I would rather have put up with it than been as alarmed as I was at his sudden rage. Poor lady! she was even then on the borderland, and she soon vanished out of our lives, though I think she is still alive, being "taken care of" in some remote district of Scotland. I quite well recollect the tragic manner in which Mr. Phillip was "taken for death" in Papa's painting-room. They had not been friends for years: I do not know why: but people had a way of disappearing now and again from our ken and then returning into it as if nothing had happened; and this occurred with Mr, Phillip. Papa had met him and made friends, and he came to give an opinion on a picture then on the easel. Something in the drawing of a nose was wrong, and Mr. Phillip took a piece of chalk and drew on the painting-table a few lines to illustrate his meaning. Suddenly he stopped, faltered, staggered, and looked at Papa, who caught him and supported him to a chair, and then he fell back insensible. Mama, I, and some of the servants came rushing at the pealing of the painting-room bell, and we were despatched in wild haste to find a doctor. None of the local ones were at home, and finally I was sent off in a hansom for Sir Henry [106/107]Thompson, who was fortunately in, and he and I came back together as fast as we could. Sir Henry and I rushed into the room, which was reeking of vinegar and burnt feathers, and Sir Henry pushed every one away and went up to Mr. Phillip. He lifted one eyelid with his finger, then he turned to Papa and said, "He will never speak again." I saw a look come over Mr. Phillip's face, which told me that, though he could not speak, he could understand. But he never did speak again; he was taken home, I fancy in Sir Henry's carriage, and lingered a few days, or it might be weeks; but the last conscious thing he did was to make that sketch, and Papa had it covered with glass, and there it remains to the present day.

Mr. Alfred Elmore was another most intimate friend, though he nearly forfeited my affection by asking me to sit to him for "Katherine" in The Taming of the Shrew, he having seen me in an unguarded moment indulging in one of the tremendous tempers which would now be called nerves, and which most certainly were augmented by foolish feeding, stuffy rooms and improper management. I had often sat to him before, but somehow Katherine was a failure, I could not always look furious, more especially as Mr. Elmore suffered fearfully from neuralgia and must have endured tortures. I have seen the perspiration pouring down his face while he worked, and he has had to go away and come back again, doubtless to take some anodyne or rest; but the pain grew so awful [107/108] that it drew up one leg and made him lame, and finally caused his death. It was an acute form of rheumatic neuralgia, caught by sleeping on the roof of one of the Dutch canal-boats, and I do not believe any one ever suffered as he did. He had one daughter, a shy, pretty girl, devoted to her father, and looked after by a most kind and excellent lady. Her mother had died in giving birth to a son, who died with her, and to us children there was always a romantic air of sorrow and suffering about the whole house. We never rioted there as we did at the Ansdells' next door, and Edith could no more have romped in the manner we romped than she could have flown.

Living just out of our district, but very close to Dickens, were the Stones. Frank Stone was a tall, handsome man, and his wife — who had a story — was born on the field of the battle of Waterloo while the battle was raging, and she told me she had always a curious impression that she had heard the guns. It may be that some ante-natal influence may have been at work, for she was severely matter-of-fact, and was not given to imagination at all. The young Stones, three of whom are yet alive, were all much older than we were, but they used to kindly condescend to allow us to play with them, and I well recollect, at the age of seven, being soundly banged and shaken by the present dignified Royal Academician Marcus, because I was too anxious to see the inside of his toy theatre, which he had carefully arranged for a performance which [108/109] was then "about to begin." The Stone family was singularly handsome. Ellen was dark, tall and stately; Bertha, who is now dead, had quantities of the most exquisitely vivid red hair, which she loathed, but lived to see the extreme of fashion. I have no vivid recollection of Arthur, who became a barrister; but Marcus was, despite his drastic treatment, greatly admired by me: he was so tall and big, and had such an amount of wonderful curly hair! I have a picture in my gallery of Mr. Stone's short way with a dreadful cook my mother had in the year of the great comet, 1858, when we were at Weymouth and Papa was detained in town on some pretext or other....

Left: The front at Weymouth. Right: The curly-haired Marcus Stone (from the Illustrated London News of 1877).

I shall not easily forget the horror we had of Weymouth in those days, and the cook did not add to our enjoyment. First of all there was that dreadful comet; it swept across the sky like the flaming sword which guarded the gates of paradise, and which was supposed to prophesy a speedy end to the world, and above all did we suffer from the close proximity of the convicts, who were always visible, and for whom we looked under our beds every night of our lives. There was no railway then from Weymouth to Portland, and we met constantly waggonette loads of the wretched men handcuffed together, and guarded by well-armed warders; we could see them swarming about in the works then in progress, and above all I was taken to see the prison by a kind friend we had, one of Her Majesty's Inspectors, who little knew what a store of agony he was laying up for me by his kindness. Now nothing of the female sex is allowed in Portland, but I recollect it all perfectly, and indeed, [110/111] though it does not sound well, there are few prisons or law courts I have not been into in England, thanks to the same friend; but Portland was a real terror to us, and we were glad to leave Weymouth because of that.

It was the last visit paid us by Mr. Stone; he was even then suffering from heart-disease, and one morning in the autumn Mrs. Stone went downstairs to get him his breakfast, leaving him to read the Times, and then get up quietly to his work when he had had some food. When she returned he was dead, his glasses still on his nose and the Times in his hand; he had simply "fallen on sleep" without a cry or a movement. When the model came, to be sent away because Mr. Stone was dead, she remarked, with all the inconsequence of her class, "Well! he might 'a let me know!" but very soon after the home was broken up; the mother went one way, the children the other, and I do not think they ever met again after the reading of the will. Mrs. Stone was a very handsome woman in her way, but personally I did not like her, and after we were married, and she stayed with me once, I never invited her again; she asked too many questions and had too many grievances, most of them fancied, to make her a pleasant inmate of any young household.

Links to related material

- The Clique (the circle of Victorian artists in which the Friths moved)

- A Chronology of Victorian Art and Culture (see 1838)

Bibliography

Panton, Jane Ellen ("Cissie"). Leaves from a Life. London: E. Nash, 1908. Internet Archive. From a copy in Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 1 January 2023.

Created 1 January 2023