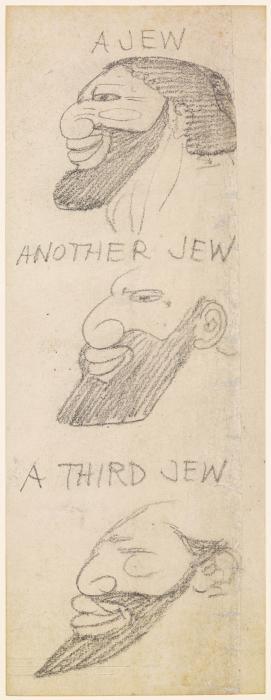

Caricature — Line of Heads by Sir Edward Coley Burne-Jones, Bt ARA (1833-1898). Dated 1877-1880. Pencil on cream-toned paper. Width: 251 mm; height: 140 mm. Collection: Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, accession number: 1927P548. Described in the collection entry as: "One of a series of anti-Semitic caricatures by Burne-Jones in Birmingham's collection relating to 'Portraits of Jews,'" this was bequeathed by James Richardson Holliday in 1927. Reproduced by kind permission of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. [Click on this and the following images for larger pictures and sometimes for more information about them.]

Commentary

In her Memorials of her husband, Georgiana Burne-Jones explains that from his schooldays Burne-Jones would entertain his friends with his drawings, which were often in the nature of caricatures: "Figure after figure, group after group would cover a sheet of foolscap almost as quickly as one could have written," she recalls a schoolfellow saying, "always without faltering or pausing, and with a look as if he saw them before him. I have seen him look straight before him into space, as if his copy were there. All the time he would be joyfully talking, and saying what he was doing or going to do." This became a settled habit which lasted his lifetime: "he must have covered reams of paper with drawings that came as easily to him as his breath. At every friend's house there are some of them." They were not pre-planned or even briefly considered. They simply "filled up moments of waiting, moments of silence, or uncomfortable moments, bringing every one together again in wonder at the swiftness of their creation, and laughter at their endless fun. Many of his school scribbles were still of 'Devils,'" she adds, "which found great acceptance among his companions." Although he evinced a keen interest in theological history in his student days, and seriously considered a clerical career, his wife recalls that "nothing escaped his sense of humour," adding that "some of his caricatures were of clergymen" (I: 38).

The need for this outlet continued: later on, drawings that Burne-Jones sent Swinburne were positively "scurrilous," and the series of obscene letters that passed between the two, and were practically all destroyed by Burne-Jones, featured "recurrent jokes" about "victimised curates and errant bishops" (MacCarthy 195). After all, by this time Burne-Jones had developed (and shared with Swinburne) a "withering contempt for established religion" (Christian 16).

Burne-Jones's A Bathing Beauty: Emma Frank, c.1873.

Clearly, one of the impulses that drove Burne-Jones to create scenes of great beauty was his disgust with what he perceived as ugly in human life. Exaggerating this ugliness, to the point of absurdity, was a way of dealing more directly with it. His sense of humour could therefore be both adolescent and crude. It could be cruel too: he not only made fun of fat women generally, but mercilessly teased his closest friend over several decades, William Morris, for his plumpness. Morris seems to have taken this in good part. Perhaps it helped that Burne-Jones caricatured himself as well, as a scruffy beanpole beside his rotund companion. But in the series of caricatures to which the Line of Heads belongs, Burne-Jones is not funny, but unforgivably offensive. Their tenor may well reflect the prejudice endemic to the times. This was, after all, an age when Morris could refer to Disraeli crossly as "the Jew wretch" (in a letter to his wife of 20 December 1877, qtd. in Thompson 215).

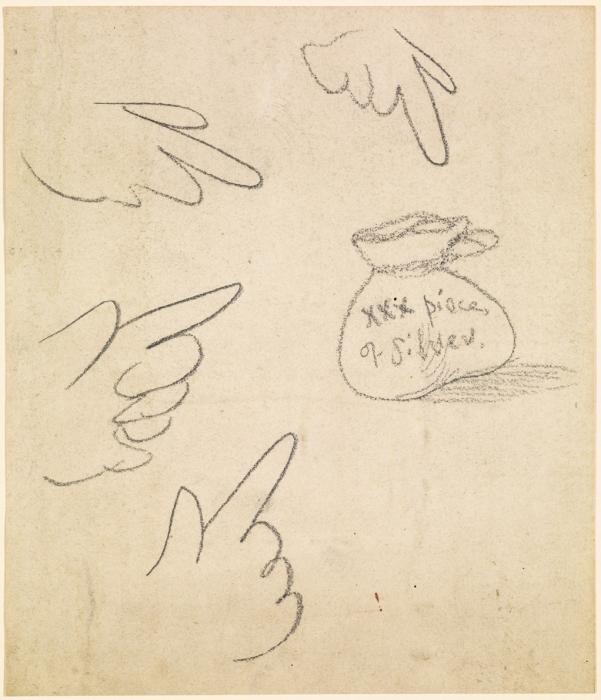

The three other drawings in the series, also bequeathed by James Richardson Holliday in 1927, accession numbers 1927949-51. Reproduced by kind permission of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery.

Burne-Jones's drawing of heads is not the worst of this handful of anti-Semitic caricatures. It simply exaggerates features and suggests shared facial characteristics, and the many people who seem to share them. The second drawing (above left) labels two similarly caricatured heads as "A Good Jew" and "A Bad Jew," as if to say that they are very much the same. The third drawing (above centre) suggests that Jewish men can only be distinguished by the way they keep their beards, while the fourth (above right) plays particularly crudely on their perceived common failing, the greed for money — a greed which is, of course, evenly distributed among the whole of mankind. By showing hands stretching towards a money-bag labelled "30 Pieces of Silver," he refers specifically to the Biblical episode of Judas Iscariot's betrayal of Jesus for personal gain. Whether Burne-Jones had in mind an individual or a personal experience when drawing these unguarded caricatures, is unknown. In fact the immediate context is unknown, and is never likely to be known.

Burne-Jones's birthplace, at 11 Benett Street (Source: Burne-Jones I, facing p.1).

However, without seeking to defend the indefensible — that is, to excuse the blatant and repulsive prejudice here — it is worth pointing out that this small set of caricatures simply cannot be the whole picture. The larger context that we do have, from his lifelong relationships with Jewish friends, suggests a very different attitude.

As is well known, Burne-Jones's mother died within a week of his birth, and for several years his grief-stricken father felt little connection with him. However, by great good fortune, next to their home at no. 11 lived "a family to whose friendship he owed much of the pleasure of his first years." His wife goes on in the Memorials to describe the household as a Jewish one, composed of an extended family,

for the two partners of a firm of merchants established in Birmingham, Messrs. Neustadt and Barnett, had married two sisters, and both families, including children, a widowed mother, and a maiden aunt, lived together under the same roof. These children were coming into the world about the same time that Edward was born, and one of his earliest memories was that of the happy life on the other side of the wall, and the kind welcome always given to him there. A member of the family now living says that he took his place among them "as a cousin," and in that house the word "cousin" meant much. They shared all their pleasures and amusements with him, nor was he excluded even from their holy days and festivals. At the Feast of Purim he dressed up with the other children, and was so eager for the merry-making that when the day came round he was always the first guest to arrive. [Burne-Jones I: 4]

From other sources, we learn that Neudstadt and Barnett was a jewellery firm, and that David Barnett (1800-1854) in particular was a prominent figure in Birmingham. Of Russian origins,

he was elected to the Birmingham Town Council in 1838 ... served as President of the Birmingham Hebrew Congregation in 1841, helped to found the local Hebrew National School, and in 1844 acted as the Jewish community’s spokesman when the civil disabilities facing Jews were discussed by councillors. In 1846 he patented an arithmetical computer. He chaired a grand ball in 1851, attended by local gentry and civic dignitaries, held in aid of a Birmingham hospital. [Rubinstein et al., 52]

Here then "was the new face of Birmingham Jewry — an energetic, enterprising industrialist, well connected, keen on religious dialogues between faiths, embodying a sense of social justice which extended beyond the boundary of his own community which he passionately sought to promote" ("Education, Rights and Resistance").

As well as spending time with this lively neighbouring family, the young Burne-Jones would also stay with the "little Neustadts and Barnetts" on holiday in Blackpool, keeping (although not without demur) both the Jewish and Christian Sabbaths when he did so (Burne-Jones I: 9). Years later, early in 1850, he took it on himself to report the safe arrival home of a member of his neighbours' family, after her trip to London. She herself was unable to write "because it was after sunset on Friday and the Jewish Sabbath" (Burne-Jones I: 42).

Simeon Solomon, daguerreotype by Frederick Hollyer, c. 1866. Reproduced with permission of Dr Carolyn Conroy.

All this might help to explain Burne-Jones's steadfast interest in and support of the younger artist Simeon Solomon. He was quick to spot Solomon's talent. Georgiana Burne-Jones writes of her husband, "I remember his telling me before we were married about a book filled with Solomon's designs, which he said were as imaginative as anything he had ever seen — here was the rising genius — to which I listened with a jealous pang! This artist afterwards became a friend of mine as well as Edward's (I: 260). Solomon also became an important member of his artistic circle, and when Solomon's trajectory went off course as a result of his arrests both in England and Paris for homosexual acts, the Burne-Joneses were among the few to stand by him.

In the memoir, Burne-Jones's wife is reticent about this. But the story is told by art historian Fiona MacCarthy. Not only did Burne-Jones continue to support Solomon, but in 1880 when Solomon became mentally unstable and appealed to them for help during his confinement in hospital, the couple "braced themselves to go and visit him and Ned wrote to his most potentially influential friends, the society solicitor George Lewis and his wife, to see if they could intervene on Solomon’s behalf." Solomon was so far reduced by now that he returned their kindness in a strange and alarming way: he came to their home at the Grange with a professional burglar, both of them considerably the worse for drink, and tried to steal the silverware. "The commotion woke the household. Georgie sent Phil [their son] to fetch a policeman. The policeman and Ned surprised the burglars. Burne—Jones was then obliged to bribe the policeman in order to save Solomon from arrest" (MacCarthy 264). What is most remarkable about this sad story of wasted talent, declining fortunes and unconscionable behaviour on Solomon's part is the ending: Burne-Jones did all he could to save him from further punishment.

Burne-Jones's Portrait of Lady Lewis, 1881 — showing how scared she is of a mouse!

Throughout his life, Burne-Jones continued to move in Jewish circles and have close Jewish friends. The lawyer mentioned above, George Lewis, was himself Jewish. He was knighted in 1893 and later, after Burne-Jones had died, became a baronet. His second wife Elizabeth was a particularly close friend of the artist, who often went to visit her in her "country retreat" at Walton-on-Thames in Surrey (MacCarthy 327), striking up a long and delightfully illustrated correspondence with one of her little daughters, Katie. A German-Jewish society hostess, Elizabeth turned to Burne-Jones when her twin brother Max Eberstadt died in 1891, and it was Burne-Jones who designed his Grade II listed tomb in Willesden Jewish Cemetery.

Burne-Jones's anti-Semitic caricatures not only lack context; they lack any relevance to what we know of his life. Belonging to what Colin Cruise calls "the shadowed side of the artist’s imagination" (117), they express something that, to the best of our knowledge, found no expression in his engagement with others. How unfortunate, if they were to turn twenty-first century art-lovers against his whole artistic endeavour! There is some danger of this. When the well-known art critic Waldemar Januszczak drew attention to them on Twitter on 12 November 2018, a number of his thousands of followers expressed outrage. Januszczak's claim that the drawings are kept "hidden in the basement at Birmingham Art Gallery" in a sort of conspiracy of silence is untrue: they are available for all to see on the gallery's website, as well as on its Pre-Raphaelite Collection website (details below). But, in view of the difficulty of making balanced judgements in this matter, one can understand why curators baulk at exhibiting the originals in the gallery itself.

Related material

- (Offsite) Line of Heads and related drawings

- Simeon Solomon: An Overview

- Sir George and Lady Lewis on their terrace at Ashley Cottage, Walton-on-Thames by James Abbot McNeill Whistler (this has more information about the Lewises)

Bibliography

Burne-Jones, Georgiana. Memorials of Edward Burne-Jones. Vol. I. London: Macmillan, 1904. Internet Archive. Contributed by Robarts Library, University of Toronto. Web. 21 November 2018.

Christian, John. "Speaking of Kisses in Paradise: Burne-Jones's Friendship with Swinburne." Journal of the William Morris Society. 13/1. Autumn 1998: 14-24.

Cruise, Colin. "An Impassioned Imagination: Burne-Jones as a Draughtsman." Edward Burne-Jones. Ed. Alison Smith. London: Tate Publishing, 2018. 75-119. [Review[].

"Education, Rights and Resistance." Connecting Histories (a partnership project led by Birmingham City Archives, working with the School of Education at the University of Birmingham, the Sociology Department at the University of Warwick, and the Black Pasts, Birmingham Futures group). Web. 21 November 2018.

MacCarthy, Fiona. The Last Pre-Raphaelite: Edward Burne-Jones and the Victorian Imagination. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2012.

Rubinstein, W, Michael A. Jolies and Hilary L. Rubinstein, eds. The Palgrave Dictionary of Anglo-Jewish History. Basingstoke and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

Thompson, E. B. William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary. Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2011.

Tomb of Max Eberstadt, Willesden Jewish Cemetery (United Synagogue Cemetery) . Historic England. Web. 21 November 2018.

Created 21 November 2018