n 18 July 1833 a young Princess was taken on an outing to Portsmouth Docks, and visited Admiral Nelson's flagship, Victory. As the future Queen Victoria recorded in her journal, the royal party "there received the salute on board. We saw the spot where Nelson fell, & which is covered up with a brazen plate & his motto is inscribed on it, 'Every Englishman is expected to do his duty.'" It was an immersive experience for the young guest: as well as tasting some long-stored drinking water, she was taken round the decks, where everything was impressively ship-shape, and sampled the sailors' fare, including some of their "Grog" (the daily ration of rum and water). She was also shown "the place where Nelson died," after being carried down below deck, fatally wounded.

Two photographs by David Spender. Left: Victory at Portsmouth Historic Dockyard. Left: Plaque marking the spot where Nelson fell, mortally wounded.

The princess's pilgrimage would inspire a lifelong fascination with the great naval hero — one that, as Queen, she would share with her people. Undoubtedly, as David Cannadine says, Nelson's "remarkable range of public interest and attention as both a fighting man and a vulnerable man" and "the triumph and tragedy of Trafalgar," help to explain his popularity after his death (2). But there was much more to the Nelson legend, and Nelson's legacy, than spontaneous adulation, and legend and legacy alike were rather more complicated than they might seem.

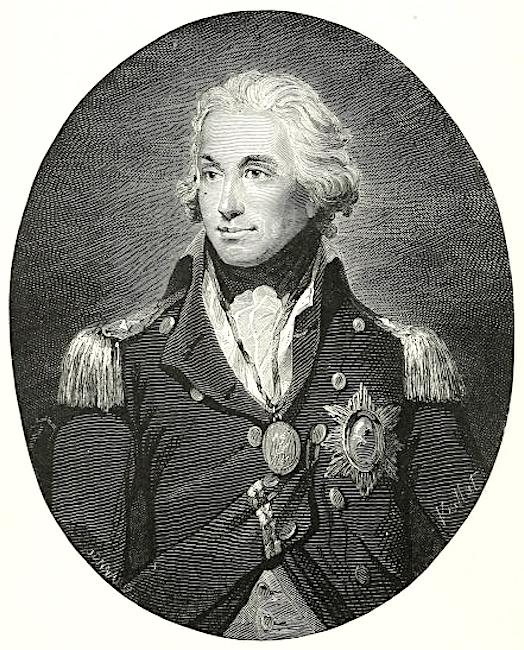

Nelson as National Hero

Admiral Lord Nelson, after the portrait by John Hoppner.

Frontispiece to Southey.

In truth, Nelson's failings did not go unnoticed. As time went by, the Queen's own approach to the great man became more nuanced. She was full of praise for Robert Southey's acclaimed The Life of Nelson, reporting in her journal entry of 14 October 1853: "The account of his death is most affecting. What a hero he was, what courage & daring. — what kindness to those around & under him! A thorough sailor, & made to be their idol, very ambitious & vain. He certainly had his faults, but the character, as a whole, was a noble one, & caused him to be intensely loved." In characterising him as vain, the Queen may have had in mind Nelson's own admission that his "consummate vanity" needed to be checked (qtd. in Southey 119) — although he used these words in the context of conventionally expressed Christian piety.

But there were other, more specific, blots on his escutcheon. One related to his behaviour in the international sphere, and indeed damaged his country's reputation. This was his betrayal of the defeated republicans in Naples in 1799, the terms of whose surrender were not simply slighted but dishonourably contravened: in an unexpected turn-about, "the garrisons, taken out of the castles, under pretence of carrying the treaty into effect, were delivered over as rebels to the vengeance of the Sicilian court. — A deplorable transaction! a stain upon the memory of Nelson, and the honour of England!" admits Southey, who adds, "To palliate it would be in vain; to justify it would be wicked: there is no alternative for one who will not make himself a participator in guilt, but to record the disgraceful story with sorrow and with shame" (170). According to Jonathan North, who has written about the episode much more recently, and at length, this reproach was well deserved, and Nelson's treachery "continued to trouble the Victorians" (Preface).

Also problematic for them was Nelson's scandalous love-life, that is, the long-term affair with Lady Hamilton, who both influenced his judgement in Naples, and led him to discard his wife. Southey himself found it "painful" to quote from his love letters at this juncture, when his wife became no more and no less than an "impediment" to his future happiness (247). As for subsequent generations, Emma Hamilton was undoubtedly "everything the Victorians reviled: sexual impropriety, adultery and even greed" (Williams 257), and not even the portrayal of her as a malign force could really excuse Nelson's thraldom.

Yet, as a matter of policy, Nelson's failings were downplayed: criticisms of his private life, for instance, "were limited to political opponents, and the bitter asides of women who feared that their husbands might become so bold as do the same" (Lambert 11). Instead and overwhelmingly, his brilliance in command, and personal bravery, were stressed. So too were the humane ideals which he professed, even if he himself fell short of them on occasion.

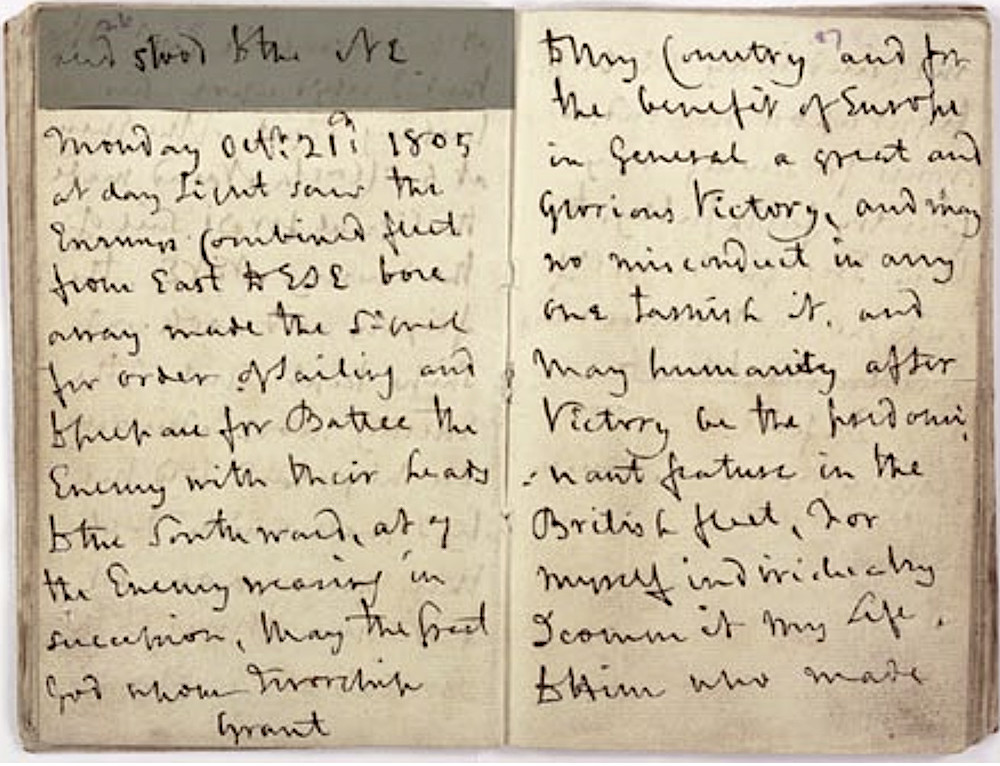

Nelson can be said to have started this process himself, and not just by force of character. "Nelson's Prayer," two copies of which were found after his death, was clearly intended for public consumption:

May the Great God whom I worship Grant to my Country and for the benefit of Europe in General a great and Glorious Victory and may no misconduct in anyone tarnish it, and may humanity after Victory be the predominant feature in the British fleet. For myself individually I commit my life to Him who made me and may his blessing light upon my endeavours for serving My Country faithfully, to Him I resign myself and the Just cause which is entrusted to me to defend. Amen amen amen. [qtd. in White, p. 93]

The positive qualities indicated here drew generations of his fellow-countrymen, and others, too, to venerate him. Despite his relatively short stature and his various injuries, and despite the ways in which he might have strayed from the path he set himself, he became a larger-than-life figure, a living legend.

The copy that appears in Nelson's last journal entry (public sector information from the National Archives, licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

Thus, when Nelson died, says Andrew Lambert, he took on "a new national role.... now he would be carefully translated from living hero in divine talisman, war god and exemplar. He was the only hope for a nation alone and without allies" (9). As the initial fervour over his victory and death began to subside, the memorialisation of Nelson was encouraged if not actually engineered both by the navy and the political establishment. On 21 June 1841, for example, the young Queen was at Woolwich dockyard for the christening of the Trafalgar, named after Nelson's famous victory. It was a splendid event, that milked the historical event for all it was worth: she called it

one of the finest sights I ever witnessed.... To see the enormous ship glide rapidly & majestically into the water, amidst the cheers of thousands & thousands, guns firing — Bands playing "Rule Britannia" was most thrilling. The river was full of steamers & ships & boats of all kinds, gaily decked out with flags, & literally groaning with the weight of people on them. The Stand we were in was on the left of the Dockyard, close to the "Trafalgar," which we visited. The actual ceremony of the Christening, was performed by Ly [Lady] Bridport Nelson's niece. The bottle of wine, which was broken on the bows of the ship had been sent by Ly Nelson, being a relic of the stock of mine [wine] Nelson had had on board the "Victory," at the Battle of Trafalgar. Crowded upon the poop were veteran survivors of that Battle....

Over the next decade or so, memories of Nelson and Trafalgar became positively hallowed. The prospect of the Duke of Wellington's funeral at St Paul's in 1852 gave the Illustrated London News a splendid opportunity to revive details of the other funeral that had taken place there on 9 January 1806. It harked back to Nelson's final obsequies in the special supplement looking forward to another such occasion, dwelling on all the events surrounding the earlier hero's death, and especially his inspiration: "Nelson had infused his own marvellous valour and superhuman confidence into the breast of every officer and seaman in his fleet" (422). Almost half a century later, the triumph at Trafalgar is relived in these columns, as is the response to that triumph — "the inexpressible pride in our navy which animated the British public" afterwards (422). Despite strong criticism of the funeral carriage itself, Nelson's funeral procession in particular is so vividly recalled that readers may have wondered if the forthcoming ceremonies for Wellington could possibly rival it.

Nelson's funeral procession, introducing the "Grand State Funeral of Lord Nelson", anticipating similar scenes for Wellington's.

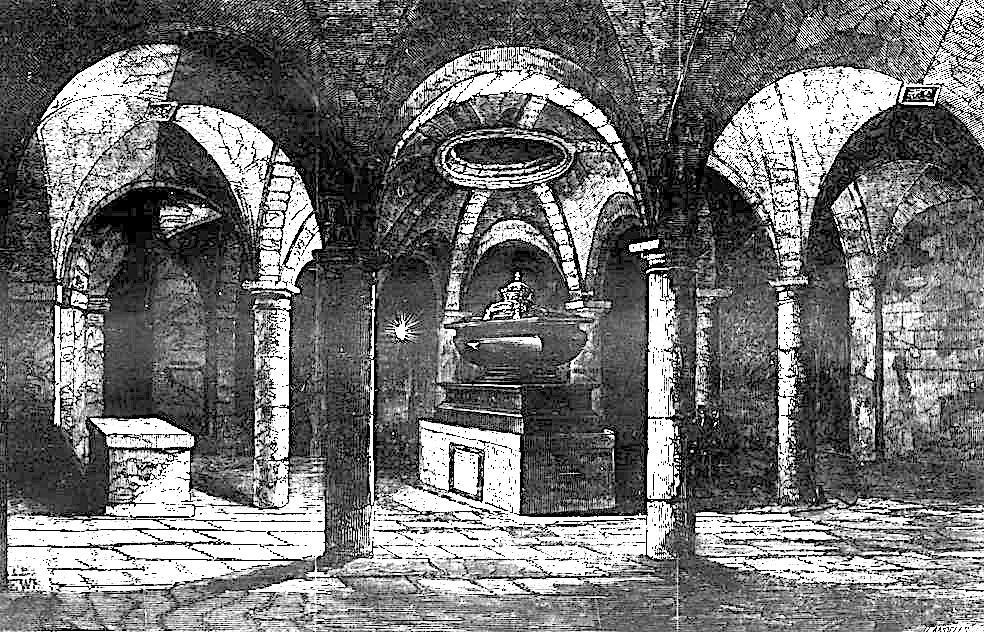

The piece concludes, "England fitly mourned her departed hero; and Ambition’s self could not have chosen a more grandly picturesque resting-place than the centre of that circle of massive pillars under the dome of St. Paul’s" (422).

Nelson's tomb in St Paul's, "Grand State Funeral," 422.

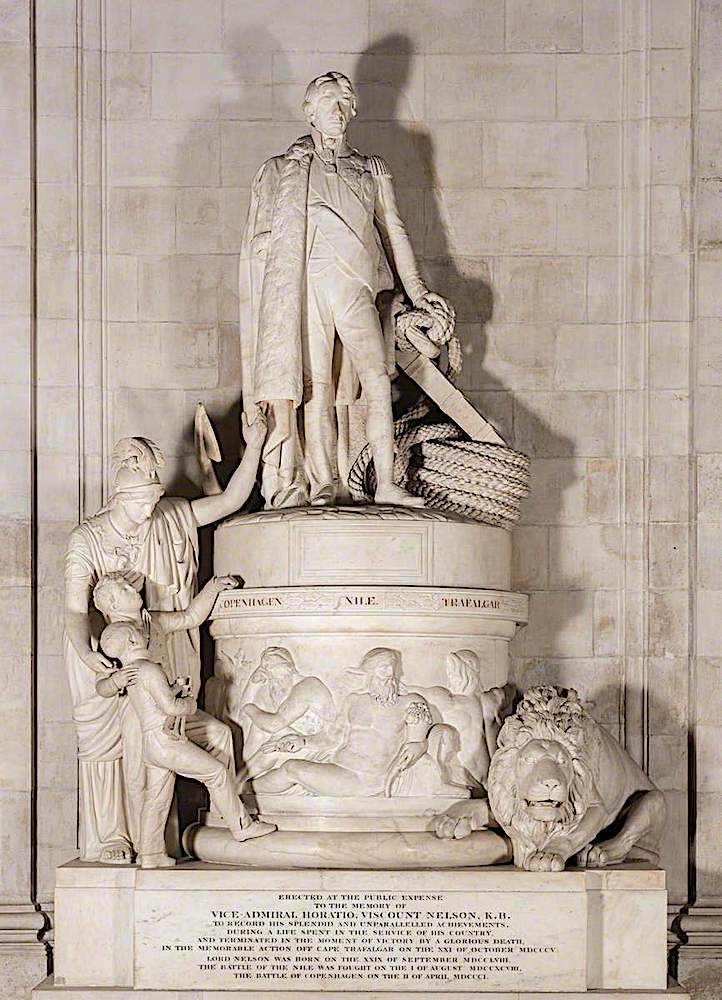

In fact, the tomb, in its place of honour at the cathedral, was only one of Nelson's many lasting commemorations. For St Paul's itself, the sculptor John Flaxman set to work on an elaborate monument that emphasized his stature as a role model for subsequent generations: from beside the pedestal, the figure of Britannia points out the hero to the two young lads in her charge.

The phenomenon of "statue mania" was current before Nelson's death (see Bullet 18), and before Flaxman could fulfil his own commission, which took him all of ten years, there was plenty of proof of it elsewhere. Other monuments to Nelson had already sprung up, notably in Birmingham and Liverpool. Later, most spectacular of all, and taking commensurately longer to deliberate on and complete, came Nelson's Column in Trafalgar Square. Its great bas-reliefs, depicting the hero's celebrated victories, were installed closer to eye-level at the base, from 1849-50, and the lions at the projecting angles of the base arrived only in 1867.

Three Nelson monuments. Left to right: (a) Matthew Cotes Wyatt and Richard Westmacott's in Birmingham, and (b) Richard Westmacott's in Liverpool. (c) Britannia encourages boys to look up to Nelson, in Flaxman's monument to him in St Paul's.

With such aids to memory, Nelson's fame glowed ever more brightly as the century wore on. At the highly successful Royal Naval Exhibition of 1891, Nelson memorabilia were proudly on display. In the end, therefore, the commemoration of Nelson, and the projection of him as a hero to be emulated, was very much a Victorian enterprise.

Nelson's Legacy

Prince Alfred, right, with his brother, the future Edward VII, dressed in sailor suits in 1853. © Royal Collection Trust / © His Majesty King Charles III 2023.

In this way, driven first by Nelson himself, and then by the establishment, "the cult of Nelson spread across the whole of nineteenth-century Britain, to the Empire beyond" (Cannadine 2). What then was the purpose of the enterprise? Lambert defines it as, quite simply, "unchallenged British global power," adding that he was "as Lord Byron declared, ‘Britannia’s God of War.’ British trade, secured by Nelson’s victory, funded both the war that destroyed the French Empire and the Industrial revolution that powered the next century of British might" (9).

Among the young Victorians to be influenced by and to contribute to this legacy was the Queen's own second son. Alfred (1844-1900) developed a "very decided liking" for the navy, as his mother noted in her journal on 27 March 1855, and was allowed to realise his ambition, rising up through the ranks to captain HMS Galatea. In this capacity, he sailed the world, visiting South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, Hawaiii, Japan, Hong Kong, India and Sri Lanka (when it was called Ceylon), eventually becoming honorary Admiral of the Fleet in 1893. Duke of Edinburgh from 1866, he was an emissary of the seat of empire, leaving mementoes along the way, from the plaque outside Prince Alfred's Court in Valetta, Malta (1858) when he was a mere midshipman, to the grand edifice of the former Royal Alfred Sailors' Home, Bombay (1872-76). Later in 1893 he succeeded to the dukedom of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, his mother noting on 3 November of that year that he was much perturbed by the prospect of his name being removed from the Navy List. But by then he had already contributed hugely to the image and preservation of the British monarchy both at home and abroad.

Yet, like the man himself, Nelson's legacy was not without its complications. The "Nelson effect" boosted the image of the navy: after a royal visit to the ships at Spithead on 18 August 1853, Queen Victoria exclaimed in her diary, "I must say one feels most proud of belonging to a country with such a Navy!" But it also raised unrealistic hopes of its performance. Michael Duffy argues that Nelson's great victory had "a downside in that Nelson and Trafalgar became the yardsticks by which naval performance was subsequently measured. Public expectations frequently demanded the impossible, for the particular, advantageous Trafalgar circumstances could never be replicated, and brave men like Sir Christopher Cradock [1862-1914] led their crews to their deaths attempting to live up to the spirit of Nelson against the odds."

Above and beyond this was the whole imperial project. This had deep roots and was already well underway before the Napoleonic wars. It is too much to lay its further development at the door of one individual, or even at the door of one institution, but the expansionist drive that followed Nelson's success in the Napoleonic wars was clearly facilitated by it, and by the top brass of the navy, playing on a wave of public euphoria.

Left: A replica of Baily's statue of Nelson on Nelson's Monument in the Nelson Room at Greenwich. Right: Emma Hamilton, from an image in the New York Public Library digital collection (Image ID 1250206).

In the long run, that project failed. Britannia no longer rules the waves. But amid the strange combination of nostalgia and hand-wringing that marks the pospostcolonial era here, something of Nelson's own glory survives. Trafalgar Day is still celebrated on 21 October, at least in the naval context, and the various monuments to Nelson continue to keep his memory alive. The Nelson Room at the Painted Hall at Greenwich, where he lay in state before his funeral, has only recently been restored, and the "Nelson, Navy, Nation" gallery at the National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, has a collection of portraits and memorabilia. These include the coat he wore at Trafalgar, originally purchased for the Greenwich Hospital by Prince Albert himself in a "publicly acclaimed gesture" (Schneider 25). His funeral hatchments and bench can still be seen in the nave of St Mary's, Merton, where he worshipped in his last years. A number of other places, such as Shepperton in Middlesex (now in Surrey), where he was given a fishing retreat after the Battle of the Nile, still boast of their connection with him.

As for his reputation, even today, historians stop short of excusing Nelson's betrayal of the republicans in Naples, although they make a point of laying part of the blame for it on Sir William Hamilton, Emma's husband, who was "the nation's minister on the spot" (Lincoln 184), and should surely have counselled him better. As for Emma herself, through the "blizzard of moralising criticism," recent critics now discern in her story "a life of multivalent importance and periodic brilliance" (Colville 9).

In short, long after the establishment first found it politic to boost Nelson's image, and long after its purpose in doing so failed, that image remains ensconced in the national consciousness. There he stands, for all his physical and human frailties, by any reckoning a great hero of the past, whose resolute leadership achieved his own immediate aim at a particular time of crisis: to preserve his country's independence, even at the cost of his own life.

Links to Monuments to Nelson, and other related material

- Plaque commemorating Nelson's stay at Fort Charles, Port Royal, Jamaica, in 1779-81 ("You who tread his footprints / remember his glory")

- Nelson Monument, Bull Ring, Birmingham, by Richard Westmacott, 1807-09

- Nelson Monument, Liverpool, by Sir Richard Westmacott (designed by Matthew Cotes Wyatt, 1813

- Nelson Monument in St Paul's Cathedral, by John Flaxman, 180-18

- Statue of Nelson on Nelson's Column, London, by E. H. Baily, 1843

- The Battle of Trafalgar [or The Death of Nelson] on Nelson's Column, by John Edward Carew, 1849

- The Battle of Copenhagan on Nelson's Column, by John Ternouth, 1850

- The Battle of the Nile on Nelson's Column, by W. F. Woodington, 1850

- The Battle of Cape St. Vincent on Nelson's Column, by M. W. Watson and W. F. Woodington, 1850

- Lions at the base of Nelson's Column, by Sir Edwin Landseer, 1867

- The Lions at last, Punch cartoon by John Tenniel

- Trafalgar Square, London

- The Battle of Trafalgar, as Seen from the Mizen Starboard Shrouds of the Victory, by J.M.W. Turner, 1806-8

- The Battle of Trafalgar, by Clarkson Stanfield, 1836

- The Victory Returning from Trafalgar, in Three Positions by J.M.W. Turner, c.1806

- The "Victory" Towed into Gibraltar, by Clarkson Stanfield, 1854

- Memorial to Frances Herbert, Viscountess Nelson, Duchess of Bronti, by Peter Turnerelli, 1831

David Spender has kindly released his photographs on the Creative Commons Licence (CC BY 2.0 Deed Attribution 2.0 Generic). You may use the other images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the source (the National Archives, Internet Archive, the Royal Collection Trust, or New York Public Library, as appropriate) and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one. [Click on all the images to enlarge them, and somerimes for more information about them.]

Bibliography

Bullet, Emma. "Some Paris Monuments." The Monumental News. I (January 1897): 18-20. Google Books. Free Ebook.

Cannadine, David. Introduction. Admiral Lord Nelson: Context and Legacy. Ed. Cannadine. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 2-4.

Colville, Quintin. "Re-imagining Emma Hamilton." Emma Hamilton: Seduction & Celebrity. Ed. Colville, with Kate Williams. London: Thames and Hudson/Royal Museums, Greenwich, 2016. 9-30.

Duffy, Michael. "Trafalgar, Nelson, and the National Memory. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Online ed. Web. 8 January 2024.

"Grand State Funeral of Lord Nelson." Illustrated London News. Vol. 21. 13 November 1852: 422. Internet Archive. Web. 8 January 2024.

Lambert, Andrew. “‘The Glory of England’: Nelson, Trafalgar and the Meaning of Victory.” The Great Circle 28, no. 1 (2006): 3–12. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41563204

Lincoln, Margarette. "Emma and Nelson. Icon and Mistress of the Nation's Hero." Emma Hamilton: Seduction & Celebrity. Ed. Quintin Colville, with Kate Williams. London: Thames and Hudson/Royal Museums, Greenwich, 2016. 175-199.

North, Jonathan. Nelson at Naples: Revolution and Retribution in 1799. Stroud, Glos.: Amberley Publishing, 2018. [Kindle ed.]

"The Royal Naval Exhibition." The Illustrated London News. 98 (9 May 1891): 614-15. Internet Archive. Web. 8 January 2024.

Schneider, Miriam Magdalena. The "Sailor Prince" in the Age of Empire: Creating a Monarchical Brand in Nineteenth-Century Europe Cham, Switzerland: Palgrave Macmillan (Springer Nature), 2017.

Southey, Robert.The Life of Lord Nelson. Ed. Edwin L. Miller. New York: Longmans, 1896. Internet Archive, from a copy in the Library of Congress. Web. 8 January 2024.

White, Colin. "Nelson Apotheosised: The Creation of the Nelson Legend." Admiral Lord Nelson: Context and Legacy. Ed. David Cannadine. London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005. 93-114.

Williams, Kate. "Emma Hamilton in Fiction and Film." Emma Hamilton: Seduction & Celebrity. Ed. Quintin Colville, with Williams. London: Thames and Hudson/Royal Museums, Greenwich, 2016. 247-70.

Created 8 January 2024