[Click on thumbnails for larger images. You may use these and the following images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer or source and (2) link your document to this URL.]

Society and Culture in Victorian Malta

Malta was a hive of expatriate activity throughout the Victorian era. Its importance as a naval base was heightened during the Crimean War, and hand in hand with that went its usefulness as an army post. For example, an old postcard shows HMS Dreadnought in the Grand Harbour with an Indian troop ship in the background. This probably dates to the late 1870s, when Malta was host to over 5,500 Indian troops and their officers, along with "1375 horses, 526 ponies and forty-three bullocks," not to mention "2340 public and private followers"! Admittedly, this was unusual: concern had been voiced beforehand about how the sepoys would adapt to such a foreign place, "without familiar bazaars, with expensive prices" and so on (Beckett 108). But many different British battalions were posted there during the period. In July 1894, for example, detachments of the East Surreys, Gloucestershires, North Staffordshires, Queen's Own Cameron Highlanders and Royal Irish Rifles were all stationed in Malta (Army and Navy Gazette). These too had their "followers." In one of her Chronicles of Service Life in Malta, Lady Winifred Fearnaught features an impecunious naval engineer who has his whole household out with him, living in Sliema: "a charming wife, a thriving and increasing family, to say nothing about a giddy widow of a sister-in-law." As for Lady Fearnaught herself, when she overturns her carriage rather than run over one of his little children, her English groom comes "tearing up" to see if she is injured (43-45).

Left: Plaque outside Prince Alfred's Court at the Grandmaster's Palace, Valletta, commemorating Prince Alfred's visit in 1858. Right: The "rainbow-tinted" fishing boats that Edward Lear saw in the bays and harbours of Malta (shown here in St Julian's Bay).

Every level of society was represented here, from top to bottom. Disraeli, who wrote rather condescendingly that "society in Malta is very refined indeed for a colony" (69) was followed in the Victorian period by members of the royal family. Queen Victoria's aunt, the dowager Queen Adelaide, came out for the winter of 1838/1840, and funded an Anglican church: St Paul's Anglican Co-Cathedral in Valletta. Prince Alfred's visit in 1858, when he was just a midshipman, is commemorated by Prince Alfred's Courtyard at the Grand Master's Palace, a sumptuous building now being used for administrative purposes. The Queen's second son, Alfred became Commander of the Mediterranean fleet, and had a long connection with Malta, spending several years there later. His third child was born there in 1877, "perhaps the only British princess ever born in a foreign dependency" (Ballou 166). The infant was named Victoria Melita, in honour of both her grandmother and Malta — the country's name being thought to have come from "malita," the Greek word for honey. British residents revelled in the presence of such people. In the introduction to her chronicles, Lady Fearnaught particularly mentions the visits of "various celebrities and royalties," and the fact that "reviews were held for their benefit, and dinners, balls and receptions given" (2).

Left: Paul Hardy's Frontispiece to Lady Fearnaught's

Visitors included both writers and artists. Sarah Grand came out in 1879 as the wife of an army surgeon. Her best-selling feminist novel, The Heavenly Twins, is set there, and has a wonderful account of sailing into the Grand Harbour. Evadne, one of the heroines, responds rhapsodically to the warmth, brightness and colour of the scene, seeing Valletta as "a great irregular enchanted palace!" (175). Among other notables, the artist and nonsense poet Edward Lear not only passed through Malta on his travels but also spent the winter of 1865-6 there. Especially delighted with Gozo, he walked miles every day drawing the scenery; it inspired some of his most appealing work. The social life was too much for him: people had no idea that artists needed peace and quiet in which to work, he complained (see Later Letters 69). But he was sad to leave Malta and his friends there. He missed the "beautiful rainbow-tinted boats of Malta or Gozo" later, when he was painting in Corsica — where the boats, he sighed, were all black (Journal 15)!

Besides service people and their families, and illustrious visitors, a whole cross-section of civilian society descended on the Crown Colony and found their level there. There were people in the shipping and shipbuilding trades, chaplains, other clergymen, teachers for the service schools, physicians and staff for the Royal Naval Hospital at Kalkara (for Malta became "The Nurse of the Mediterranean" as well as its supply hub), dentists, police inspectors and sergeants, post-office and telegraph clerks, outfitters, booksellers, all kinds of other retailers, a master baker for the naval bakery, porters, and so forth, again often with families in tow. A huge variety of occupations was represented (see "British Residents, 1800-1900"). The more cultivated could enjoy E.M. Barry's Royal Opera House and the Manoel Theatre, the latter having been remodelled in 1812 by General Sir George Whitmore (1775-1862) of the Royal Engineers, and rechristened the Royal Theatre. Others frequented the bars, clubs and seamier establishments of Strait Street, or "Gut Street" as it came to be known. George Meredith imagines his naval hero, Nevil Beauchamp, encountering someone special amid the bevy of young women in port: "And that girl in Malta! I wonder what has become of her! What a beauty she was!" exclaims his friend Jack Wilmore, in a context that suggests that the girl was Maltese (he mentions an Armenian, and a peasant girl in Granada as well).

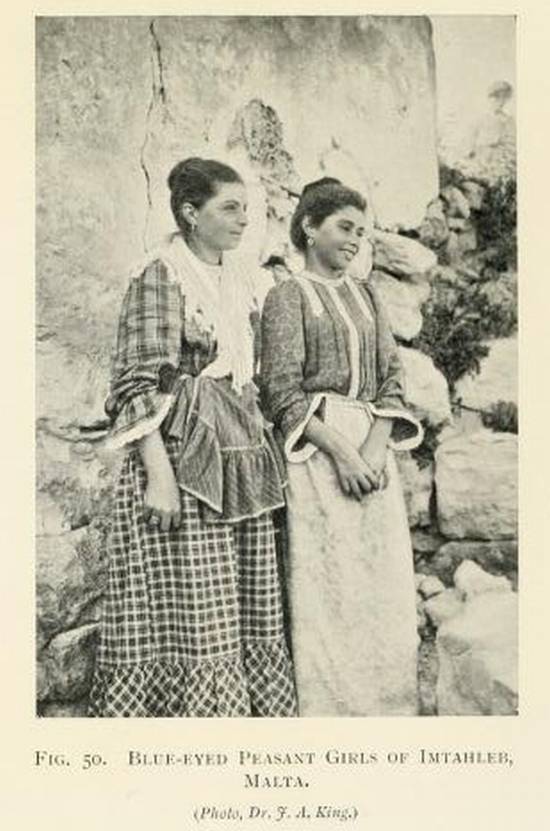

Peasant girls of Malta. Note the lace shawl and trimmings. Photograph by Dr. J. A. King, from Bradley, facing p.188.

"No one there takes their lives seriously, except the real islanders," wrote Lady Fearnaught in her introduction (3). Naturally, British rule and the large British presence impinged greatly on the Maltese themselves. How much it benefited them is a contentious issue. Some do seem to have been better off now. Opportunities for trade and commerce had greatly increased. An oft-cited example from early in the period is the introduction of the potato by Sir Alexander Ball, not a trivial matter because it became an important export crop for the country. Dock-working, provisioning and ship-chandelling gave employment to many. Meanwhile, efforts were made to maintain the people's own cultural traditions. Queen Victoria's encouragement of the old art of lace-making, by putting in an order for mitts and a shawl, was greatly appreciated (see the lacework in her statue in Republic Square). As a result, even the poor were able to obtain a modicum of enjoyment from their lives (see Mallia-Milanes 161). There were some new pleasures, too. When the Indian troops arrived in the 70s, they were eager to participate in "cricket, football, pigeon shooting, tennis, racquets, polo and running" with the British forces (Beckett 110). The Maltese were interested as well. After the first Association Football match between the garrison at Marsa and the Royal Engineers in 1882, Maltese football teams were formed to play against the forces, and the Malta Football Association was founded in 1900 ("Malta Football Association: History"). Of much wider general importance was the gradual replacement (not without significant constitutional issues along the way) of Italian by English as an official language of Malta, alongside Maltese.

Nevertheless, many of the Maltese continued to live in poverty. The basic problem was that Malta was being administered by military men first and foremost as a military base. This inevitably bred mistrust, and led to a difference in priorities, even to the extent of misgovernment (see Mallia-Milanes 192). Accustomed as they were to a ruling class not drawn from their own ranks, the people had expected more of the British. There was support for the Maltese even in England. The outspoken Liberal MP for Glasgow, George Anderson, for example, made an indignant address to the House of Commons on 28 July 1882: "Our Maltese fellow-subjects had always been remarkable for their devotion to us, and yet we had done very little to encourage them," he proclaimed. "The Maltese were not a conquered people; they asked to come under the protection of England about 80 years ago; but, notwithstanding that, we had done almost nothing during that lapse of years to conciliate their devotion and loyalty." The language barrier, he pointed out, still prevented all but a few (about 2,000 out of 150,000!) Maltese from voting. Another objection was to a system of taxation that spared the rich "and thus pressed heavily upon the poor. One-half of the taxation was levied upon bread, and as it was evident that a poor man and his family consumed more bread than the family of the rich man — the rich man having other and better diet — the poor man was not only taxed beyond his means, but paid a far greater share of the taxes than his rich neighbours" (Hansard). Laxity in education reform was another bone of contention.

Left: A statue of the popular Franciscan, Fra Diegu Bonanno (1831-1902), who was disturbed to see so many outcasts on the streets, and opened shelters for destitute and abandoned girls from the 1860s onwards (by Censu Apap, 1932, St Paul's Square in Hamrun; see Scerri). Right: The Old University, a baroque building dating from 1592. In 1900, it only had 86 students, all of them male. It was really only for the wealthy, who could afford their own books (see "Economic and Social Issues").

Population growth, coupled with a poor economic outlook, had already driven many Maltese to emigrate, principally to North Africa. In the later 1880s, food prices did fall somewhat, increasing the real value of wages, and making the Maltese more prosperous (see Mallia-Milanes 151). But booms and slumps were common, depending on how much naval activity was going on in the Mediterranean, and an early twentieth-century visitor arriving in Malta noted not its unique fortifications but the "swarming hoards of the unemployed who throng the shore and some of the public squares of the city [Valletta]," adding, "the manifest poverty of the prolific lower classes of Malta is appalling to the political economist" (Bradley 167). It was perhaps mainly in their large engineering projects that the Victorians benefited Malta, tugging the little Crown Colony after them into the modern age.

Note

Nina Stuart introduces her "friend" Lady Fearnaught's collection of stories, ostensibly written by a service wife who accompanied her husband to Malta on several occasions from the early 1850s to the 1880s, by which time he had risen to become the General of an infantry brigade. But the book is dedicated to the memory of Captain Arthur Thomas Stuart of the Royal Navy, "and to all navy officers." It may be significant that Fearnought (with an "o") was the nickname of the Dreadnought, shown in the Grand Harbour here.

Links to related material

- The Victorians in Malta: Part I (Background)

- The Victorians in Malta: Part III (Architecture and Civil and Military Engineering Projects)

- The Role of the Victorian Army

- Imperial and Postimperial Rhetorics of Benevolence. A Review of Helen Gilbert and Chris Tiffin's Burden or Benefit?

Bibliography

Ballou, Maturin M. The Story of MaltaThe Story of Malta. Boston & New York: Houghton, Mifflin: 1893.

Beckett, Ian F. W. The Victorians at War London: Hambledon & London, 2003.

Bradley, Robert Noel. Malta and the Mediterranean Race. London: Fisher Unwin, 1912.

Disraeli, Benjamin. Home Letters Written by the Late Earl of Beaconsfield in 1830 and 1831. Whitefish, MT: Kessinger, 2004.

"Economic and Social Issues during the Nineteenth Century" (a Government of Malta educational site, no longer available). Viewed 25 March 2010.

Fearnaught, Lady Winifred. Chronicles of Service Life in Malta London: Edwin Arnold, 1908. Viewed 25 March 2010.

Grech, Jesmond. British Heritage in Malta. Sesto Florentino (Fi): Centro Stampa Editoriale (Plurigraf), 2003.

Hansard (excerpt available here.) Viewed 25 March 2010.

Lear, Edward. Journal of a Landscape Painter in Corsica. London: Robert John Bush, 1870.

_____. Later Letters of Edward Lear to Chichester Fortescue (Lord Carlingford), Frances Countess Waldegrave and Others. London: Fisher Unwin, 1911.

Mallia-Milanes, Victor, ed.. The British Colonial Experience, 1800-1964: The Impact on Maltese Society. Msida, Malta: Mireva, 1988.

"Malta Family History" (no longer available). Viewed 25 March 2010.

"Malta Football Association: History." Updated 6 June 2016.

Meredith, George. Beauchamp's Career. London: Constable, 1909.

Scerri, John N. "Important People: Fra Diegu Bonanno" (no longer available). Viewed 25 March 2010.

"Stations of the British Army, 21 July 1894." Army and Navy Gazette, 1894 (no longer found online). Viewed 25 March 2010.

Created 25 March 2010

Last modified 14 July 2022