These edited extracts are from Paget's own account, The Light Cavalry Brigade in the Crimea: Extracts from the Letters and Journal of General Lord George Paget (John Murray, 1881). Alvin Wee of the University Scholar's Programme, created the electronic text using OmniPage Pro OCR software, and created the HTML version. Edited and added by Marjie Bloy, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore. [Click on the footnote numbers to return to the main text.]

The disposition of the brigade was as follows:

| Left. | Centre. | Right. | |

| 1st Line . . | 11th Hussars. | 17th Lancers. | 13th Light Dragoons. |

| 2nd Line . . | . . | 4th Light Dragoons. |

8th Hussars. |

-- the second line (under me) being formed up about 100 yards in rear of the first line, (under Lord Cardigan).

The first line started off (down somewhat of a decline) at a brisk trot, the second line following though at rather a decreased pace, to rectify the proper distance of 200 yards.

When I gave the command to my line to advance, I added the caution, "The 4th Light Dragoons will direct." [This must be specially borne in mind.]

Before we had proceeded very far, however, I found it necessary to increase the pace to keep up with what appeared to me to be the increasing pace of the first line, and after the first 300 yards my whole energies were exerted in their directions, my shouts of "Keep up; come on," etc., being rendered the more necessary by the stoical coolness (which made such an impression on me at the time) of my two squadron leaders, Major Low and Captain Brown, whose shouts still ring in my ears of "Close in to your centre back the right flank; keep up, Private So-and-so. Left squadron keep back; look to your dressing," etc — sounds familiar to one's ears on the Fifteen Acres, or Wormwood Scrubbs, but hardly perhaps to be expected on such a job as ours, and showing how impervious they were to all that was going on around them, and how impossible it was for them, even under such circumstances, to forget the rules of parade, but which perhaps had the effect of checking the unusual pace at which the first line was leading us.

The 4th and 8th, as I have said, composed the second line, under my command. I led in front of the right squadron of the 4th (the directing regiment). After we had continued our advance some 300 or 400 yards' distance, I began to observe that the 8th were inclining away from us, and consequently losing their interval. At the top of my voice I kept shouting, " 8th Hussars, close in to your left. Colonel Shewell, you are losing your interval," etc.; but all to no purpose. Gradually — my attention being equally occupied with what was going on in my front ("Mind, your best support, my Lord," being ever present in my mind) — I lost sight of the 8th, and shall for the present speak no more of them, but hereafter revert to the subsequent actions of that regiment.

The

Charge of the Light Brigade from William Simpson's The Seat of War in the

East, second series. I am grateful to John Sloan for

permission to use this image from the Xenophongi

web site and which graciously he has agreed to share with the Victorian Web.

Copyright, of course, remains with him. Click on the image for a larger view There was no one, I believe, who, when he started on this advance, was insensible

to the desperate undertaking in which he was about to be engaged; but I shall

not easily forget the first incidents that confirmed what before was but surmise.

Ere we had advanced half our distance, bewildered horses from the first line,

riderless, rushed in upon our ranks, in every state of mutilation, intermingled

soon with riders who had been unhorsed, some with a limping gait, that told

too truly of their state. Anon, one was guiding one's own horse (as willing

as oneself in such benevolent precautions) so as to avoid trampling on the bleeding

objects in one's path — sometimes a man, sometimes a horse — and so we went

on " Right flank, keep up. Close in to your centre." The smoke, the

noise, the cheers, the groans, the "ping, ping" whizzing

past one's head; the "whirr" of the fragments of shells; the

well-known "slush" of that unwelcome intruder on one's ears!

— what a sublime confusion it was! The "din of battle!" —

how expressive the term, and how entirely insusceptible of description! One incident struck me forcibly about this time — the

bearing of riderless horses in such

circumstances. I was of course riding by myself and clear of the line, and for

that reason was a marked object for the poor dumb brutes, who were by this time

galloping about in numbers, like mad wild beasts. They consequently made dashes at me, some advancing with me a considerable

distance, at one time as many as five on my right and two on my left, cringing

in on me, and positively squeezing me, as the round shot came bounding by them,

tearing up the earth under their noses, my overalls being a mass of blood from

their gory flanks (they nearly upset me several times, and I had several times

to use my sword to rid myself of them). I remarked their eyes, betokening as

keen a sense of the perils around them as we human beings experienced (and that

is saying a good deal). The bearing of the horse I was riding, in contrast to

these, was remarkable. He had been struck, but showed no signs of fear, thus

evincing the confidence of dumb animals in the superior being! [Or in better

language, as I have somewhere read, "This shows how lower natures, being

backed by higher, increase in courage and strength. Truly man being backed by

Omnipotency is a kind of omnipotent creature!"] And so, on we went through this scene of carnage, wondering each moment which

would be our last. "Keep back, Private So-and-so. Left squadron, close

in to your centre." (It required, by the bye, a deal of closing in, by

this time, to fill up the vacant gaps.) A Lancer is now seen on our left front prodding away at a dismounted Russian

officer, apparently unarmed. I holloa to him to let him alone, which he obeys,

though reluctantly (for their monkeys are up by this time), and the act, while

it was not very graciously acknowledged by the officer in question, was begrudged

by some who saw it. But to return to the charge, or more properly in MY opinion to be termed the

"advance." We had advanced perhaps some 300 or 400 yards, when I perceived that the 11th

Hussars (which regiment started on the left of the first line began to disengage

itself from that line, by dropping back, decreasing their pace gradually, and

inclining to their right, apparently to cover the other regiment (1)

of the first line. From this moment I of course directed my movements in accordance with those

of that regiment. The 8th Hussars had by this time, as I have shown, left me,

and I was consequently advancing with the 4th alone. Seeing therefore that the

11th were thus slacking their pace, and were themselves forming a second line,

and being simultaneously left with my own regiment alone, I then commenced my

endeavour by a still more increased pace to form a junction with the 11th, and

thus with them form a line of support, the result of which will presently be

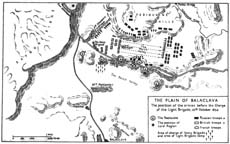

shown; but I must now for the present occupy myself with the doings of the 4th. This

map is taken from Christopher Hibbert's The Destruction of Lord Raglan,

p. 134, with the author's kind permission. Copyright, of course, remains with

him. Click on the image for a larger view A line of field artillery was formed up across the plain in our front, consisting

of at least twelve guns. This battery, owing to the dust and confusion that

reigned, had not been perceived by us (by me at least) until we got close upon

it, though we had of course been suffering from its fire on our onward course.

The first objects that caught my eyes were some of these guns, in the act of

endeavouring to get away from us, who had by this time got close upon them.

They had, I fancy, ceased to fire on our near approach, and the men were dragging

them away, some by lasso-harness, but others with their horses still attached.

Then came a "Holloa!" and a sort of simultaneous rush upon them by

the remnants of the 4th and cut and thrust was the order of the day. (2) To some of the guns, however, horses were attached, and some of the drivers

of these, in the mêlée, tried to let themselves fall off between

the horses. There were some fierce hand-to-hand encounters, and our fellows, in the excitement

of the moment, lost sight, I fear, of the chief power of their sabres, and for

the point (the great efficacy of which was amply exemplified on this

day) substituted the muscle of their arms, in the indiscriminate appliance of

the cut, which generally fell harmlessly on the thick greatcoats of the Russians.

[The state of many of the hands after the encounter bore proof of this. Captain

Brown's sword-hand, for instance, had actually a bad sore for many days after,

for it must be remembered that no one wore gloves, and the hands were grated

by the rough handles of the swords.] Well, the work of destruction went on, of which I, however, was a passive observer,

conceiving it more within the province of my duty to observe and endeavour to

direct, than to occupy myself with the immediate destruction of the foe. [Oddly

enough, the possession of a revolver never entered my head, and the only act

of mine, on this day, as regards immediate destruction was that of saving an

officer's life, and happy for me has since been the reflection of this, for

doubtless the revolver would have been a tempting weapon more than once, had

I thought of it.] It is impossible too highly to admire the devotion, the entire

absence of all sense of danger, on the part of the officers through this crisis,

but while perhaps surprise may not be felt at those acts committed in the excitement

of the moment by those who found themselves for the first time in a position

to which, as far as it engendered excitement, the finest run in Leicestershire

could hardly bear comparison — at the same time it admits of a grave doubt

whether it comes within the province of those whose duty it is to direct and

command, to occupy themselves, as some did on that day, in the description of

combat belonging more properly to the Dragoon. The four or five guns to which I have alluded as being more immediately in

our front, were soon disabled, one of them — that which was the more immediately

under my notice, and the process of the dismemberment of which I had been more

closely observing — having been overturned. (3)

While the 4th were thus engaged, I observed twenty or thirty yards ahead two

or three of the guns scrambling away, drawn by horses with lasso-harness, which

it was evident had thus been attached, so that they might be dragged away at

the very last moment, on which I said to Captain Brown, who was close to me,

"There are some guns getting away, take some of your men to stop them,"

which order, I need not say, was promptly and effectually obeyed. It should

have been recorded of this officer that he was, I always understood, the only

subaltern in the Cavalry Division who never missed one day's duty throughout

the whole war. We must now turn to the movements of the 11th Hussars. I have said that my attention had been, almost from the first, directed to

their movements, and I soon perceived that they were apparently pursuing a course

rather inclining to the left of that pursued by the first line. Colonel Douglas

accounted for this as follows. (4) As he was approaching the point of the high hill (the last of the chain of

the Fedioukine heights) that overlooks the plain, and round the base of which

the valley makes rather a bend to the left as it approaches the Tchernaya, he

perceived in the distance, some Russian cavalry in the plain, formed up in the

sort of open valley or gorge which leads down (as I have said) to the river.

He thought that by a vigorous attack on these troops he might bear them down,

and drive them on to the river, being little aware of the masses of cavalry

by which they were supported. With this object, then, he passed by the guns

in the plain without engaging them [it will be seen in Colonel Douglas's account

that a portion of his right squadron engaged with the guns], there being an

interval between these guns and the base of the hill sufficient for his regiment

(if regiment it could by this time be called) to pass through in line. He therefore

went on thus with the 11th, and it may be fairly said that on this occasion

about forty men of the "Cherubims" [a sobriquet by which the 11th

Hussars were known, from their cherry-coloured overalls, but which will not

bear further translation] advanced against the entire force of the Russian cavalry!

indeed, the Russian army! Here Colonel Douglas soon became aware of the masses of cavalry that were drawn

up in support of the comparatively few that he had already seen the level of

the ground having prevented him from seeing the main body sooner. He nevertheless

went on with his regiment, ALONE, and advanced some distance, until he was absolutely

driven back, and compelled to retrace his steps. I must now again turn to the 4th. I have said that it had been my endeavour

to overtake and form a junction with the 11th. Now when we (the 4th) had got

up to the guns, our front rank had nearly, if not quite, got up to the rear

rank of the 11th (on their right) but our onward course was at this moment necessarily

checked by our contact with the guns, which are directly in our line

of advance. The 11th consequently again got away from us. When those guns had

been disposed of, as I have shown, which did not occupy a long space of time,

the 4th (by this time resembling more a party of skirmishers than a regiment),

leaving the disabled guns behind them, pursued their onward course after the

11th, still, as I imagined, in support of the first line — Lord Cardigan's

words always ringing in my ears. They (the 11th) had by this time been compelled

to retire, and we consequently soon met their compact little knot retreating.

When we met, the 4th hesitated, stopped, and without word of command "went

about," joining themselves to the retiring 11th. Masses of the enemy's cavalry were pursuing the latter, the more forward of

them (who were advancing in far from an orderly manner, and evincing that same

air of surprise, hesitation, and bewilderment that I had remarked in their advance

against the Heavy Brigade in the morning — appearing not to know what next

to do) being close upon us. It now appeared to me that the moment was critical,

and I shouted at the top of my voice, "Halt, front; if you don't front,

my boys, we are done!" (5) and this they

did, and for a few minutes both regiments showed a front to the advancing enemy.(6)

Hardly, however, had we thus rallied, when a cry arose, "They are attacking

us, my Lord, in our rear!" I turned round, and on looking in that direction

saw there, plainly enough, a large body of Russian Lancers formed up, some 500

yards behind us, in the direct line whence we had originally come, and on the

direct line of our retreat! On the impulse of the moment, I then hollaed out,

"Threes about " — adding, "We must do the best we can for ourselves,"

the latter portion of the sentence being directed probably to the officers within

hearing. [I recollect that at this moment Major Low was close to me on my left,

and he has since told me that I said to him, "We are in a desperate scrape;

what the devil shall we do? Has any one seen Lord Cardigan?"] But by this

time, and indeed long previously, all order and regularity of formation had

been lost; but still there was a sort of nucleus left whereon a fresh "rally"

might be made to encounter our new foes, and this was to a certain extent effected

by the individual exertions of the officers, from Colonel Douglas, Major Low

and myself, down to the subalterns, my eye happening to catch at the moment

Lieutenant Joliffe, Captain Brown and Lieutenant Hunt with their swords held

in mid-air, to the cry of " Rally, rally!" when some few stragglers

from the first line (which had long ago been broken up) joined us. [Major Low

about this time, that is after we had effected our new semblance of formation,

and were commencing our retreat or rather advance on the Lancers, said to me,

"I say, Colonel, are you sure those are not the

17th?" to which I replied, " Look at the colour of their flags."] Helter-skelter then we went at these Lancers as fast as our poor tired horses

could carry us, rear rank of course in front (as far as anything by this time

could be called a "front"), the officers of course in the rear, for

it must be remembered that we still had our pursuers behind us. When we first saw them, the formation of the Lancers in our rear appeared to

be that of a contiguous close column, and formed up right across our path; and

as we approached them I remarked the regular manner in which they executed the

movement of throwing their right half back, thus seemingly taking up

a position that would enable them to charge down obliquely upon our right flank,

as we passed them, and that would also have the effect of getting them more

out of the line of fire from their own batteries to the south. [I must acknowledge

that the regularity with which they seemingly executed this movement engendered

in my mind grave misgivings as to what would be the result when we came into

contact — we being little more than a rabble of 60 or 70 men, while they were

a compact body, apparently about the frontage of two squadrons, and two or three

squadrons deep: a sort of double column of squadrons, regularly formed up, and

having first effected with regularity a somewhat difficult movement.] On seeing their tactics, I (from the rear) shouted out, "Throw up your

left flank," when we had made a near approach to them, my object being

to show them a parallel front, but in the din and noise that prevailed my voice

probably reached but a few, and it must be owned that no attempt was made at

this crisis to show a front, the general endeavour being to edge away to

the left (I know not how otherwise to express that for which there is certainly

no military phrase). Well, as we neared them, down they came upon us at a sort of trot (their advance

not being more than twenty or thirty yards), they stopped ("halted"

is hardly the word) and evinced that same air of bewilderment (I know of no

other word) that I had twice before remarked on this day. A few of the men on the right flank of their leading squadrons, going farther

than the rest of their line (as flanks are apt to do when halted), came into

momentary collision with the right flank of our fellows, but beyond this, strange

as it may sound, they did nothing, and actually allowed us to shuffle, to edge

away, by them, at a distance of hardly a horse's length. [I can only say that

if the point of my sword crossed the ends of three or four of their lances,

it was as much as it did, and I judge of the rest by my own case, for there

was not a man, at that moment, more disadvantageously placed than myself (being

behind and on the right rear).]. Well, we got by them without, I believe, the

loss of a single man. How, I know not! It is a mystery to me! Had that force

been composed of English ladies, I don't think one of us could have escaped!

(7) It had now for some time been a case somewhat of the "sauve qui peut"

["save himself, who can"] with us, and there was no attempt at pursuit.

They knew too well the sort of reception they would share with us, did they

attempt to follow us through the ordeal we had before us, ere we got straight

home, and thus the very danger that we had before us was a source of safety

to us. A ride of a mile or more was before us, every step of which was to bring

us more under the fire from the heights on either hand (though on one side partially

silenced by the disabling of a battery by the Chasseurs d'Afrique during our

absence, but of which we were of course at the time ignorant). And what a scene

of havoc was this last mile strewn with the dead and dying, and all friends!

some running, some limping, some crawling; horses in every position of agony,

struggling to get up, then floundering again on their mutilated riders! Mine was an unenviable position, for I had had a "bad start," and

my wounded horse at every step got more jaded, and I therefore saw those in

my front gradually increasing the distance between us, and I made more use of

my sword in this return ride than I had done in the whole affair. However, with

the continual application of the flat of it against my horse's flank and the

liberal use of both spurs, I at last got home, after having overtaken Hutton,

who had been shot through both thighs, and who was exerting the little vigour

left in him in urging on his wounded horse, as I was mine. (8) Well, there is an end to all things, and at last we got home, the shouts of

welcome that greeted every fresh officer or group as they came struggling up

the incline, telling us of our safety. (9) I must now give an account of the remainder of my original command, that is,

of the proceedings of the 8th Hussars. I have said that soon after our start I perceived that the 8th were gradually

inclining away to their right; that all my efforts were of no avail in keeping

them in their places; that they thus by degrees disengaged themselves from us,

and that my attention being occupied in the movement of those in front of us,

I lost sight of, and thought no more of them. It appears that something of the

following kind occurred: Colonel Shewell in the advance was leading, or rather in front of (for

technically the squadron leader only leads) the left squadron of his

regiment, Major de Salis riding in advance of the right squadron. The former heard all my shouts, and by his corresponding ones did all in his

power to rectify the interval which his regiment was losing, and which was getting

wider at every step. Not only were the 8th losing their interval from the 4th,

but the right squadron of the 8th were inclining away from their left, squadron.

Colonel Shewell saw all this as well as myself, and did his utmost to rectify

it, (10) the result being, that not only was

the interval between the two regiments lost, but by the same process the 8th

Hussars fell equally behind the alignment, the necessary result,

when one body goes straight, and the other, if going at the same pace, inclines.

After this I saw no more of the 8th Hussars.

We must turn now to the proceedings of the first line, under the immediate

command of Lord Cardigan, which are as follows, as far as I know them: The direction taken by this line was down the centre of the valley for a considerable

distance, after which, while the 11th took a direction to the left, the first

line inclined towards the right, as they approached the guns in position. It will thus be seen that while the first line was originally composed of the

11th, 13th, and 17th, the order received by Colonel Douglas, during his advance,

to drop behind the first line, for the reasons given by him, resulted in the

advance of his regiment down the left of the valley; while therefore the first

line originally consisted of those regiments, the actual first line, which was

led by Lord Cardigan up to the guns, consisted of the 13th and 17th, and it

is with these only that I have now to do. The character of the advance, or rather the disposition of the several regiments,

at the time when we had got about halfway down the valley, was as follows: The 13th and 17th were advancing in one line down the right of the valley. The left of the enemy's guns was thus attacked by the 13th and 17th, and subsequently

by the 8th, and the right of the enemy's guns was attacked by the 11th and 4th. I believe the number of guns formed up in the plain was eighteen, the frontage

of about ten of which was attacked by the 13th, 17th, and 8th, while the remainder

were attacked by the 4th, except perhaps about two on their extreme right, which

were attacked by the right troop of the 11th. When the first line had got through their guns, they went struggling on, amidst

desperate encounters of all sorts, but of which I of course was not a witness,

the general feature of their movements being a sort of sweep round to their

left, towards the Tchernaya, reaching in their course to the base of the rising

ground to their front, and making the larger circle, to the inner one made by

US. And probably each regiment in turn must have approached to about the, same

distance, from the Tchernaya, the regiments on the right must of course have

gone over the most ground. They were then, after many desperate encounters of all sorts, overpowered (as

we were subsequently) by the overwhelming forces opposed to them, and they struggled

home by twos and threes, some of them passing us when we were engaged on the

left, some few gluttons uniting to our "rally." It was the complete dispersion of those regiments that prevented my impractised

eye from seeing that the successive knots of men retreating constituted, in

fact, the whole of those who escaped; a more perfect appreciation of which would

probably have lessened the pertinacity with which I kept urging on our advance,

to the, tune of "Mind, your best support, my Lord," for of course,

had I known at the time that there was nothing left to support, the force of

that injunction would have, ceased to exist. It is self-evident that in this glance at the operations of the first line

I know little more than from the rumours common to all. Suffice it to say that,

as regards the advance, all the regiments engaged had probably an equal share

in the fighting, though there can be no doubt that the second line had in the

retreat a severe crisis, to which they only were exposed — that of having to

meet a very strong force of cavalry, formed up to cut off their retreat. I must now refer to the events which were passing, while we were down at the

Tchernaya. As I rode home, I remember the, impression made on my mind on seeing the Chasseurs

d'Afrique (the 4th Regiment commanded by Colonel Champeron), appearing as

if they had just been turned out of so many bandboxes, advancing towards us

at a walk at the head of the valley, with a line of skirmishers in their front,

and forming a strange contrast to our dusty and tired soldiers. I thought to

myself as I gazed on them, " You are very pretty to look at, but you might

as well have taken a turn with us, and then perhaps you would not look as spruce

as you do." But I little knew the good service they had been rendering

us during our absence. This regiment, as I afterwards learnt, or a portion of it, had, on seeing the

mischief that a battery from the Fedioukine heights on our left had been causing

us during our advance, gallantly attacked and silenced it, thus relieving us

from the fire on that side on our return, and an important diversion in our

favour it was; but one, the description of which I will not attempt, as I only

speak of those events that came under my own eye, and for the same reason I

can say nothing of the operations of our Heavy Brigade during our absence. P.S. — I have said that my orderly, Parkes, was wounded and taken prisoner,

as was also my trumpeter, Crawford. They returned to us from Russia, in December

1855, at Scutari, and from them I heard some very graphic details, both of the

battle, and also of what subsequently befell them in captivity. They had neither of them, it appears, been unhorsed till on their way home,

and both when near each other. They then ran on foot (Crawford being slightly

wounded) for a long way towards home, when Parkes was shot in his sword-hand

and had to give himself up. During their progress they were attacked by several

parties, consisting of three or four Cossacks each, who, however, always kept

at a respectful distance. On one of the last occasions a Russian officer rode

up, and, seeing that they were about to be roughly handled, said to Parkes in

English, "If you will give yourself up, you shall not be hurt," which,

however, he declined to do. Shortly after, he was wounded and was thus compelled to do so, and then seeing

the officer still near him, he placed himself and Crawford under his protection,

and they were taken by him to General Liprandi's tent, when he was asked by

the General a great many questions as to the English army, their position, numbers,

etc., as Parkes stated in his blunt way, "We tried all we could to deceive

the General," who (though in a joking way, as he described it) said, "You

are a liar, and I know more about the English than you will tell me." The General would hardly believe that he was a Light Dragoon (he was about

six feet two inches high), and said, " If you are a Light Dragoon what

sort of men are your Heavy Dragoons?" Liprandi then said that it was well known that all the Light Brigade were drunk

that morning; and when Parkes assured him that neither he nor any of his comrades

had put a morsel of food or drop of drink in their mouths that day, he said,

"Well, my boy, you shall not remain in that state long," and he called

to an aide-de-camp and told him to give the prisoners a plentiful allowance

of food and drink. They were the next day started off for the interior of Russia, marching on

foot most of the way, and though at first they were not treated with much consideration,

the treatment became better as they went on, resulting ultimately in every sort

of kindness and attention from every one, Parkes winding up his description

thus: "Ay, my Lord, the officers were not ashamed of being seen walking

about with us." Parkes likewise told us that there was a rifleman behind every bush in the

end of the valley, taking pot shots at us as we approached, which fact he learned

from the Russians. He also told me that when he and Crawford were running home

together, they fell in with Halkett, whom they found with a bad body wound (this

must have been some time after all the firing had ceased). In accordance with

his cries, Crawford lifted him on to Parkes' back, and he carried him a short

distance, when, to save himself from attacks from the Cossacks, knots of whom

were hovering around, he was forced to let him down and leave him. In returning

shortly after, as prisoners, they found him dead and naked, with the exception

of his jacket. (1) I was extremely puzzled at seeing this, but afterwards

ascertained from Colonel Douglas that, almost immediately after the commencement

of the advance, he received an order direct from Lord

Lucan, conveyed by an aide-de-camp of his, that be should thus drop back

and form a support to the first line, thus (consequently) constituting us the

third line, though I was unaware of this fresh disposition till afterwards. (2) It was about this time that my orderly, Private Parkes,

a fine specimen of an Englishman, about six feet two inches high, who had lost

sight of me in the mêlée, came rushing past me, his sword up in

the air, and holloaing out, "Where's my chief?" to which I answered,

"Here I am, my boy, all right," — the last I saw of him, for he had

his horse shot under him, was himself wounded, and afterwards take prisoner. (3) It was at this moment, and I think with reference to

this gun that the following took place. Lieutenant Hunt, 4th Light Dragoons,

was close to my right, when, before I could stop him, or rather before my attention

was drawn to him, he returned his sword, jumped off his horse, and began trying

to unhook the traces from this gun! the only acknowledgment of this act of devotion

being, I fear, a sharp rebuke, and an order to remount. When the circumstances

are considered in which he committed this act, it must be acknowledged that

it was a truly heroic one. He thus disarmed himself in the mêlée,

amid hand-to-hand encounters, and the act which he attempted would have been

a most useful one, had support been near to retain possession of the gun which

he was trying to dismember, though under the circumstances it was of course

a useless attempt — but none the less worthy of record and of a Victoria Cross,

for which he would have been recommended, had the choice lain with me.

(4) The following details are the result of conversations

I afterwards had with Douglas, but in addition to this I find the following

remark made in my Journal, after he had perused what I am now going to narrate.

"In making this attack on the Russian cavalry, I thought I should have

been supported, and that our infantry were coming from Balaclava. A Russian

officer, covered with decorations, surrendered to me in passing through the

guns. "(Signed) J. DOUGLAS, Colonel." (5) At this moment, I remember with what force, occurred

to my mind an expression I had often beard from the lips of Lord Anglesey: "Cavalry

are the bravest fellows possible in an advance, but once get them into a scrape,

and get their backs turned, and it is a difficult matter to stop, or rally them."

And now, thought I, would this be verified? The few that were left together

(amounting probably to about 60 or 70 in the two regiments) HALTED AND FRONTED

AS IF THEY HAD BEEN ON PARADE! (6) Lieut. Martyn, Acting Adjutant of the 4th, who was close

to me all the time, has since told me, that when I rallied the two regiments

here and had fronted them, I ordered a fresh advance, which was only stopped

by his and Major Low's expostulating with me, and pointing out the masses before

us (for behind the broken few who were so close upon us, and through them as

it were, were to be seen the main body advancing). To this I can only express

my belief that they were mistaken, for to the best of my recollection I never

meditated a fresh advance, my object in fronting being to save us from immediate

and inevitable destruction, which object, be it observed, was gained by the

front which we — I must say judiciously — showed those who were the nearest

to us, and who were thus for the moment checked in their advance. We, the 4th, advanced as we did, because until the 11th fell back on us, we

were acting in their support, but from the moment when these two regiments were

united, it would have been clearly an act of madness (if indeed it had been

possible) to have attempted another advance. I must attribute the supposition in the mind of those officers to this — that

by the act of fronting I intended to advance, for I cannot think that I gave

the order. The difference between showing a momentary front to an overwhelming

enemy and attempting another advance is, in my opinion, very great, the latter

being in the highest degree imprudent, nay impossible. (7) It should be here explained that these Lancers ("Teropkine,"

I believe) must have debouched out of the road leading on to the valley from

the Tractir Bridge, after we had passed by the road on our advance, the point

at which they were formed up to cut off our retreat being that where the road

issues on the valley. If it were a preconcerted trap on their part, it was a

well-conceived one, and had it been equally well followed up, would have been

fatal to us. (8) The doings of this brave fellow deserve record. He was

shot through the right thigh during the advance, and holloaed out to his squadron

leader, "Low, I am wounded, what shall I do?" to which the latter

replied, " If you can sit on your horse, you had better come on with us

; there's no use going back now, you'll only be killed." He went on, and if report speaks truly, made good use of his powerful arm in

disabling some of the enemy. On his return he was shot through his other thigh

(he ultimately recovered), his horse being hit in eleven places. When I overtook

him, he complained of feeling faint, and asked if I could give him a little

rum, which I fumbled out of my holster as we were going along. He then naïvely

said, "I have been wounded, Colonel; would you have any objection to

my going to the doctor when I get in?" (This all under a heavy fire!) (9) One of the first of the many who rode up to greet me on

my safe return was Lord Cardigan, riding composedly from the opposite direction. The involuntary exclamation escaped me, "Holloa, Lord Cardigan! were not

you there? " to which he answered, "Oh, wasn't I, though! Here, Jenyns,

did not you see me at the guns?" I then said, "I am afraid there are no such regiments left as the 13th

and 17th, for I can give no account of them," but before I had finished

the sentence, I caught sight of a cluster of them standing by their horses,

on the brow of the hill, in my front (10) Lieutenant Martyn, Acting-Adjutant 4th Light Dragoons,

told me afterwards that, hearing my vociferations, he galloped off to Colonel

Shewell (whether by my order or not, he does not recollect, but he thinks that

I ordered him) and said, " Lord George is holloaing to you to close in

to the 8th," to which he replied, I know it, I bear him, and am doing my

best. Last modified 24 August 2024

The 11th were advancing (somewhat in echelon to the first line) in rather

an oblique direction towards the left of the valley.

The 4th were advancing in support of the 11th, and somewhat to their right

in echelon to them.

The 8th Hussars to the right of the 4th, and in echelon to them, but following

the course of the first line to the right.Notes