The Reason Why (New York, McGraw-Hill 1953) pp. 242-59. Chew Yong Jack of the University Scholar's Programme, created the electronic text using OmniPage Pro OCR software, and created the HTML version. Edited and added by Marjie Bloy, Ph.D., Senior Research Fellow, National University of Singapore.

Lord Cardigan rode up and said, 'Lord George, we are ordered to make an attack to the front. You will take command of the second line, and I expect your best support-mind, your best support'. Cardigan, who was very much excited, repeated the last sentence twice very loudly, and Lord George, rather irritated, replied as loudly, 'You shall have it, my lord.' It was the first intimation Lord George had had of an intended attack; he thought it was permissible to keep his cigar, and noticed that it lasted him until he got to the guns.

Lord Cardigan now hastened at a gallop back to his troops and drew the brigade up in two lines: the first the 13th Light Dragoons, 11th Hussars and the 17th Lancers; the second the 4th Light Dragoons and the main body of the 8th Hussars. A troop of the 8th Hussars, under Captain Duberly, had been detached to act as escort to Lord Raglan.

At the last moment Lord Lucan irritatingly interfered and ordered the 11th Hussars to fall back in support of the first line, so that there were now three lines, with the 13th Light Dragoons and the 17th Lancers leading. Lord Lucan's interference was made more annoying by the fact that he gave the order, not to Cardigan, but directly to Colonel Douglas, who commanded the 11th. Moreover, the 11th was Cardigan's own regiment, of which he was inordinately proud, and the 11th was taken out of the first line, while the 17th Lancers, Lucan's old regiment, remained.

Lord Cardigan meanwhile had placed himself quite alone, about two lengths in front of his staff and five lengths in advance of his front line. He now drew his sword and raised it, a single trumpet sounded, and without any signs of excitement and in a quiet voice he gave the orders, 'The Brigade will advance. Walk, march, trot,' and the three lines of the Light Brigade began to move, followed after a few minutes' interval by the Heavy Brigade, led by Lord Lucan. The troop of Horse Artillery was left behind because part of the valley was ploughed.

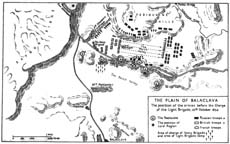

The North Valley was about a mile and a quarter long and a little less than a mile wide. On the Fedioukine Hills, which enclosed the valley to the north, were drawn up eight battalions of infantry, four squadrons of cavalry and fourteen guns; on the Causeway Heights to the south were the bulk of the eleven battalions, with thirty guns and a field battery which had captured the redoubts earlier in the day; at the end of the valley, facing the Light Brigade, the mass of the Russian cavalry which had been defeated by the Heavy Brigade was drawn up in three lines, with twelve guns unlimbered before them, strengthened by six additional squadrons of Lancers, three on each flank. The Light Brigade was not merely to run a gauntlet of fire: it was advancing into a deadly three-sided trap, from which there was no escape.

The Brigade was not up to strength, cholera and dysentery having taken their toll — the five regiments present could muster only about 700 of all ranks, and both regiments in the first line, the 17th Lancers and the 13th Light Dragoons, were led by captains, Captain Morris and Captain Oldham respectively.

Nevertheless, the Brigade made a brave show as they trotted across the short turf. They were the finest light horseman in Europe, drilled and disciplined to perfection, bold by nature, filled with British self-confidence, burning to show the 'damned Heavies' what the Light Brigade could do.

As the Brigade moved, a sudden silence fell over the battlefield: by chance for a moment gun- and rifle-fire ceased, and the watchers on the heights felt the pause was sinister. More than half a century afterwards old men recalled that as the Light Brigade moved to its doom a strange hush fell, and it became so quiet that the jingle of bits and accoutrements could be clearly heard.

The Brigade advanced with beautiful precision, Lord Cardigan riding alone at their head, a brilliant and gallant figure. It was his great day: he was performing the task for which he was supremely well fitted, no power of reflection or intelligence was asked of him, dauntless physical courage was the only requirement, and he had, as Lord Raglan said truly, 'the heart of a lion'. He rode quietly at a trot, stiff and upright in the saddle, never once looking back: a cavalry commander about to lead a charge must keep strictly looking forward; if he looks back his men will receive an impression of uncertainty.

He wore the gorgeous uniform of the 11th Hussars, and, living as he did on his yacht, he had been able to preserve it in pristine splendour. The bright sunlight lit up the brilliance of cherry colour and royal blue, the richness of fur and plume and lace; instead of wearing his gold-laced pelisse dangling from his shoulders, he had put it on as a coat, and his figure, slender as a young man's, in spite of his fifty-seven years, was outlined in a blaze of gold. He rode his favourite charger, Ronald, 'a thoroughbred chestnut of great beauty', and as he led his Brigade steadily down the valley towards the guns he was, as his aide-de-camp Sir George Wombwell wrote, 'the very incarnation of bravery'.

Before the Light Brigade had advanced fifty yards the hush came to an end: the Russian guns crashed out and great clouds of smoke rose at the end of the valley. A moment later an extraordinary and inexplicable incident took place. The advance was proceeding at a steady trot when suddenly Nolan, riding beside his friend Captain Morris in the first line, urged on his horse and began to gallop diagonally across the front. Morris thought that Nolan was losing his head with excitement, and, knowing that a mile and a quarter must be traversed before the guns were reached, shouted, 'That won't do, Nolan! We've a long way to go and must be steady.' Nolan took no notice; galloping madly ahead and to the right, he crossed in front of Lord Cardigan — an unprecedented breach of military etiquette — and, turning in his saddle, shouted and waved his sword as if he would address the Brigade, but the guns were firing with great crashes, and not a word could be heard. Had he suddenly realised that his interpretation of the order had been wrong, and that in his impetuosity he had directed the Light Brigade to certain death? No one will ever know, because at that moment a Russian shell burst on the right of Lord Cardigan, and a fragment tore its way into Nolan's breast, exposing his heart. The sword fell from his hand, but his right arm was still erect, and his body remained rigid in the saddle. His horse wheeled and began to gallop back through the advancing Brigade, and then from the body there burst a strange and appalling cry, a shriek so unearthly as to freeze the blood of all who heard him. The terrified horse carried the body, still shrieking, through the 4th Light Dragoons, and then at last Nolan fell from the saddle, dead.

Lord Cardigan, looking strictly straight ahead and not aware of Nolan's death, was transported with fury. It was his impression that Nolan had been trying to take the command of the Brigade away from him, to lead the charge himself; and so intense was his rage that when he was asked what he thought about as he advanced towards the guns, he replied that his mind was entirely occupied with anger against Nolan.

The first few hundred yards of the advance of the Light Brigade covered the same ground, whether the attack was to be on the guns on the Causeway Heights or the guns at the end of the valley. The Russians assumed that the redoubts were to be charged, and the watchers on the heights saw the Russian infantry retire first from Redoubt No. 3 and then from No. 2 and form hollow squares to receive the expected charge; but the Light Brigade, incredibly, made no attempt to wheel. With a gasp of horror, the watchers saw the lines of horsemen continue straight on down the North Valley.

The Russian artillery and riflemen on the Fedioukine Hills and the slopes of the Causeway Heights were absolutely taken by surprise; it was not possible to believe that this small force trotting down the North Valley in such beautiful order intended to attempt an attack on the battery at the end of the valley, intended, utterly helpless as it was, to expose itself to a cross fire, of the most frightful and deadly kind, to which it had no possibility of replying. There was again a moment's pause, and then from the Fedioukine Hills on one side and the Causeway Heights on the other, battalion upon battalion of riflemen, battery upon battery of guns, poured down fire on the Light Brigade.

Charge of the Light Brigade by R. Caton Woodville. This page graciously has been shared with the Victorian Web by from Stephen Luscombe, from his website, The British Empire, and to whom thanks are due. Copyright, of course, remains with him.

Click on the image for a larger view.

When advancing cavalry are caught in a withering fire and are too courageous to think of retreat, it is their instinct to quicken their pace, to gallop forward as fast as individual horses will carry them and get to grips with the enemy as soon as possible. But Lord Cardigan tightly restrained the pace of the Light Brigade: the line was to advance with parade-ground perfection. The, inner squadron of the 17th Lancers broke into a canter, Captain White, its leader, being, he said, 'frankly anxious to get out of such a murderous fire and into the guns as being the lesser of two evils', and he shot forward, level with his brigadier. Lord Cardigan checked him instantly; lowering his sword and across Captain White's breast, he told him sharply not to ride level with his commanding officer and not to force the pace. Private Wightman of the 17th Lancers, riding behind, heard his stern, hoarse voice rising above the din of the guns, 'Steady, steady, the 17th Lancers.' Otherwise during the whole course of the charge Lord Cardigan neither spoke nor made any sign.

All he could see at the end of the valley as he rode was a white bank — of smoke, through which from time to time flashed great tongues of flame marking the position of the guns. He chose one which seemed to be about the centre of the battery and rode steadily for it, neither turning in his saddle nor moving his head. Erect, rigid and dauntless, his bearing contributed enormously to the steadiness, the astonishing discipline which earned the Charge of the Light Brigade immortality.

And now the watchers on the heights saw that the lines of horsemen, like toys down on the plain, were expanding and contracting with strange mechanical precision. Death was coming fast, and the Light Brigade was meeting death in perfect order; as a man or horse dropped, the riders on each side of him opened out; as soon as they had ridden clear the ranks closed again. Orderly, as if on the parade-ground, the Light Brigade rode on, but its numbers grew every moment smaller and smaller as they moved down the valley. Those on the heights who could understand what that regular mechanical movement meant in terms of discipline and courage were intolerably moved, and one old soldier burst into tears. It was at this moment that Bosquet, the French General, observed, 'C'est magnifique mais, ce n'est pas la guerre' [it is magnificent, but it isn't war].

The fire grew fiercer; the first line was now within range of the guns at the end of the valley, as well as the fire pouring from both flanks. Round-shot, grape and shells began to mow men down not singly, but by groups; the pace quickened and quickened again — the men could no longer be restrained, and the trot became a canter.

The Heavy Brigade were being left behind; slower in any case than the Light Cavalry, they were wearied by their earlier action and, as the pace of the Light Brigade quickened, the gap began to widen rapidly. At this moment the Heavy Brigade came under the withering cross-fire which had just torn the Light Brigade to pieces. Lord Lucan, leading the Brigade, was wounded in the leg and his horse hit in two places; one of his aides was killed, and two of his staff wounded. Looking back, he saw that his two leading regiments — the Greys and the Royals — were sustaining heavy casualties. In the Royals twenty-one men had already fallen. Lord Lucan's indifference under fire was remarkable: it was on this occasion that an officer described as 'one of his most steady haters' admitted, 'Yes, damn him, he's brave', but he felt himself once more in a dilemma. Should he continue to advance and destroy the Heavy Brigade, or should he halt and leave the Light Brigade to its fate without support? He turned to Lord William Paulet, who was riding at his side and had just had his forage cap torn off his head by a musket ball. 'They have sacrificed the Light Brigade: they shall not the Heavy, if I can help it,' he said. Ordering the halt to be sounded, he retired the brigade out of range and waited, having decided in his own words that 'the only use to which the Heavy Brigade could be turned was to protect the Light Cavalry against pursuit on their return'.

With sadness and horror the Heavy Brigade watched the Light Brigade go on alone down the valley and vanish in smoke. Help now came from the French. As a result of General Canrobert's earlier order the Chasseurs d'Afrique were drawn up beneath the heights. Originally raised as irregular cavalry, this force, which had a record of extraordinary distinction, now consisted of French troopers, mounted on Algerian horses.

Their commander, General Morris, had seen the Light Brigade fail to wheel and advance down the valley to certain doom with stupefied horror. Nothing could be done for them, but he determined to aid the survivors. He ordered the Chasseurs d'Afrique to charge the batteries and infantry battalions on the Fedioukine Hills. Galloping as if by a miracle over broken and scrubby ground in a loose formation learned in their campaigns in the Atlas mountains of Morocco, they attacked with brilliant success. Both Russian artillery and infantry were forced to retreat, and at a cost of only thirty-eight casualties — ten killed and twenty-eight wounded — the fire from the Fedioukine Hills was silenced. Such remnants of the Light Brigade as might return would now endure fire only on one flank: from the Causeway Heights.

The first line of the Light Brigade was now more than halfway down the valley, and casualties were so heavy that the squadrons could no longer keep their entity: formation was lost and the front line broke into a gallop, the regiments racing each other as they rode down to death. 'Come on,' yelled a trooper of the 13th to his comrades, 'come on. Don't let those b��s of the 17th get in front of us.' The men, no longer to be restrained, began to shoot forward in front of their officers, and Lord Cardigan was forced to increase his pace or be overwhelmed. The gallop became headlong, the troopers cheering and yelling; their blood was up, and they were on fire to get at the enemy. Hell for leather, with whistling bullets and crashing shells taking their toll every moment, cheers changing to death-cries, horses falling with a scream, the first line of the Light Brigade — 17th Lancers and 13th Light Dragoons — raced down the valley to the guns. Close behind them came the second line. Lord George Paget, remembering Lord Cardigan's stern admonition, 'Your best support mind, your best support', had increased the pace of his regiment, the 4th Light Dragoons, and caught up the 11th Hussars. The 8th Hussars, sternly kept in hand by their commanding officer, Colonel Shewell, advanced at a steady trot, and refused to increase their pace. The second line therefore consisted of the 4th Light Dragoons and the 11th Hussars, with the 8th Hussars to the right rear.

As they, too, plunged into the inferno of fire, and as batteries and massed riflemen on each flank began to tear gaps in their ranks and trooper after trooper came crashing to the ground, they had a new and horrible difficulty to face. The ground was strewn with casualties of the first line — not only dead men and dead horses, but horses and men not yet dead, able to crawl, to scream, to writhe. They had perpetually to avoid riding over men they knew, while riderless horses, some unhurt, some horribly injured, tried to force their way into the ranks. Troop-horses in battle, as long as they feel the hand of their rider and his weight on their backs, are, even when wounded, singularly free from fear. When Lord George Paget's charger was hit, he was astonished to find the horse showed no sign of panic. But, once deprived of his rider, the troop-horse becomes crazed with terror. He does not gallop out of the action and seek safety: trained to range himself in line, he seeks the companionship of other horses, and, mad with fear, eyeballs protruding, he attempts to attach himself to some leader or to force himself into the ranks of the nearest squadrons. Lord George, riding in advance of the second line, found himself actually in danger. The poor brutes made dashes at him, trying to gallop with him. At one moment he was riding in the midst of seven riderless horses, who cringed and pushed against him as round-shot and bullets came by, covering him with blood from their wounds, and so nearly unhorsing him that he was forced to use his sword to free himself.

And all the time, through the cheers, the groans, the ping of bullets whizzing through the air, the whirr and crash of shells, the earth-shaking thunder of galloping horses' hooves, when men were not merely falling one by one but being swept away in groups, words of command rang out as on the parade-ground, 'Close in to your centre. Back the right flank! Keep up, Private Smith, Left squadron, keep back. Look to your dressing.' Until at last, as the ranks grew thinner and thinner, only one command was heard: 'Close in! Close in! Close in to the centre! Close in! Close in!'

Eight minutes had now passed since the advance began, and Lord Cardigan, with the survivors of the first line hard on his heels, galloping furiously but steadily, was within a few yards of the battery. The troopers could see the faces of the gunners, and Lord Cardigan selected the particular space between two guns where he intended to enter. One thought, wrote a survivor, was in all their minds: they were nearly out of it at last, and close on the accursed guns, and Lord Cardigan, still sitting rigid in his saddle, 'steady as a church', waved his sword over his head. At that moment there was a roar, the earth trembled, huge flashes of flame shot out and the smoke became so dense that darkness seemed to fall. The Russian gunners had fired a salvo from their twelve guns into the first line of the Light Brigade at a distance of eighty yards. The first line ceased to exist. To the second line, riding behind, it was as if the line had simply dissolved. Lord Cardigan's charger Ronald was blown sideways by the blast, a torrent of flame seemed to belch down his right side, and for a moment he thought he had lost a leg. He was, he estimated, only two or three lengths from the mouths of the guns. Then, wrenching Ronald's head round, he drove into the smoke and, charging into the space he had previously selected, was the first man into the battery. And now the Heavy Brigade, watching in an agony of anxiety and impatience, became aware of a sudden and sinister silence. No roars, no great flashes of flame came from the guns — all was strangely, menacingly quiet. Nothing could be seen: the pall of smoke hung like a curtain over the end of the valley; only from time to time through their glasses the watchers saw riderless horses gallop out and men stagger into sight to fall prostrate among the corpses of their comrades littering the ground.

Fifty men only, blinded and stunned, had survived from the first line. Private Wightman of the 17th Lancers felt the frightful crash, saw his captain fall dead; then his horse made a 'tremendous leap into the air', though what he jumped at Wightman never knew — the pall of smoke was so dense that he could not see his arm before him — but suddenly he was in the battery, and in the darkness there were sounds of fighting and slaughter. The scene, was extraordinary: smoke so obscured the sun that it was barely twilight, and in the gloom the British troopers, maddened with excitement, cut and thrust and hacked like demons, while the Russian gunners with superb courage fought to remove the guns.

While the struggle went on in the battery, another action was taking place outside. Twenty survivors of the 17th Lancers — the regiment was reduced to thirty-seven men — riding behind Captain Morris had outflanked the battery on the left, and, emerging from the smoke, suddenly found themselves confronted with a solid mass of Russian cavalry drawn up behind the guns. Turning in his saddle, Morris shouted, 'Now, remember what I have told you, men, and keep together', and without a moment's hesitation charged. Rushing himself upon the Russian officer in command, he engaged him in single combat and ran him through the body. The Russians again received the charge halted, allowed the handful of British to penetrate their ranks, broke and retreated in disorder, pursued by the 17th. Within a few seconds an overwhelming body of Cossacks came up, the 17th were forced to retreat in their turn, and, fighting like madmen, every trooper encircled by a swarm of Cossacks, they tumbled back in confusion towards the guns. Morris was left behind unconscious with his skull cut open in two places.

Meanwhile in those few minutes the situation in the battery had completely changed. In the midst of the struggle for the guns, Colonel Mayow, the Brigade Major, looked up and saw a body of Russian cavalry preparing to descend in such force that the men fighting in the battery must inevitably be overwhelmed. Shouting, 'Seventeenth! Seventeenth! this way! this way!' he collected the remaining survivors of the 17th and all that was left of the 13th Light Dragoons — some twelve men — and, placing himself at their head, charged out of the battery, driving the Russians before him until he was some 500 yards away.

At this moment the second line swept down. The 11th Hussars outflanked the battery, as the 17th had done; the 8th Hussars had not yet come up, but the 4th Light Dragoons under Lord George Paget crashed into the battery. So great was the smoke and the confusion that Lord George did not see the battery until his regiment was on top of it. As they rode headlong down, one of his officers gave a 'View halloo', and suddenly they were in and fighting among the guns. The Russians gunners, with great courage, persisted in their attempt to take the guns away, and the 4th Light Dragoons, mad with excitement, fell on them with savage frenzy. A cut-and-thrust, hand-to-hand combat raged, in which the British fought like tigers, one officer tearing at the Russians with his bare hands and wielding his sword in a delirium of slaughter. After the battle this officer's reaction was so great that he sat down and burst into tears. Brave as the Russians were, they were forced to give way; the Russian gunners were slaughtered, and the 4th Light Dragoons secured absolute mastery of every gun.

While this fierce and bloody combat was being waged, Colonel Douglas, outflanking the battery with the 11th Hussars, had charged a body of Lancers on the left with considerable success, only to find himself confronted with the main body of the Russian cavalry and infantry in such strength that he felt he was confronted by the whole Russian army. He had hastily to retreat with a large Russian force following in pursuit.

Meanwhile the 4th Light Dragoons, having silenced the guns, had pressed on out of the battery and beyond it. Lord George had, he said, an idea that somewhere ahead was Lord Cardigan, and Lord Cardigan's admonition enjoining his best support was 'always ringing in his ears'. As they advanced they collided with the 11th in their retreat, and the two groups, numbering not more than seventy men, joined together. Their situation was desperate. Advancing on them were enormous masses of Russian cavalry — the leading horsemen were actually within a few hundred yards; but Lord George noticed the great mass was strangely disorderly in its movements and displayed the hesitation and bewilderment the Russian cavalry had shown when advancing on the Heavy Brigade in the morning. Reining in his horse, Lord George shouted at the top of his voice, 'Halt front; if you don't front, my boys, we are done'. The 11th checked, and, with admirable steadiness, the whole group 'halted and fronted as if they had been on parade'. So for a few minutes the handful of British cavalry faced the advancing army. The movement had barely been completed when a trooper shouted, 'They are attacking us, my lord, in our rear', and, looking round, Lord George saw, only 500 yards away, a formidable body of Russian Lancers formed up in the direct line of retreat. Lord George turned to his major: 'We are in a desperate scrape; what the devil shall we do? Has anyone seen Lord Cardigan?'

When Lord Cardigan dashed into the battery he had, by a miracle, passed through the gap between the two guns unhurt, and in a few seconds was clear — the first man into the battery and the first man out. Behind him, under the pall of smoke, in murk and gloom, a savage combat was taking place, but Lord Cardigan neither turned back nor paused. In his opinion, he said later, it was 'no part of a general's duty to fight the enemy among private soldiers'; he galloped on until suddenly he was clear of the smoke, and before him, less than 100 yards away, he saw halted a great mass of Russian cavalry. His charger was wild with excitement and before he could be checked Lord Cardigan had been carried to within twenty yards of the Russians. For a moment they stared at each other, the Russians utterly astonished by the sudden apparition of this solitary horseman, gorgeous and glittering with gold. By an amazing coincidence, one of the officers, Prince Radzivill, recognised Lord Cardigan — they had met in London at dinners and balls — and the Prince detached a troop of Cossacks with instructions to capture him alive. To this coincidence Lord Cardigan probably owed his life. The Cossacks approached him, but did not attempt to cut him down and after a short encounter in which he received a slight wound on the thigh he evaded them by wheeling his horse, galloped back through the guns again, and came out almost where, only a few minutes earlier, he had dashed in.

By this time the fight in the guns was over and the battery, still veiled with smoke, was a hideous, confused mass of dead and dying. The second line had swept on, and Lord George Paget and Colonel Douglas, with their handful of survivors, were now halted, with the Russian army both in front of them and behind them, asking 'Where is Lord Cardigan?'

Lord Cardigan, however, looking up the valley over the scene of the charge, could see no sign of his brigade. The valley was strewn with dead and dying; small groups of men — wounded or unhorsed — were struggling towards the British lines; both his aides-de-camp had vanished; he had ridden never once looking back, and had no idea of what the fate of his brigade had been. Nor had he any feeling of responsibility — in his own words, having 'led the Brigade and launched them with due impetus, he considered his duty was done'. The idea of trying to find out what had happened to his men or of rallying the survivors never crossed his mind. With extraordinary indifference to danger he had led the Light Brigade down the valley as if he were leading a charge in a review in Hyde Park, and he now continued to behave as if he were in a review in Hyde Park. He had, however, he wrote, some apprehension that for a general his isolated position was unusual, and he avoided any undignified appearance of haste by riding back very slowly, most of the time at a walk. By another miracle he was untouched by the fire from the Causeway Heights, which, although the batteries on the Fedioukine Hills had been silenced by the French, was still raking the unfortunate survivors of the charge in the valley. As he rode he continued to brood on Nolan's behaviour, and on nothing else. The marvelous ride, the dauntless valour of the Light Brigade and their frightful destruction, his own miraculous escape from death, made no impression on his mind; Nolan's insubordination occupied him exclusively, and when he reached the point where the Heavy Brigade was halted, he rode up to General Scarlett and immediately broke into accusations of Nolan, furiously complaining of Nolan's insubordination, his ride across the front of the brigade, his attempt to assume command and., Lord Cardigan finished contemptuously, 'Imagine the fellow screaming like a woman when he was hit'. General Scarlett checked him: 'Say no more, my lord; you have just ridden over Captain Nolan's dead body'.

Meanwhile the seventy survivors of the 4th Light Dragoons and 11th Hussars under Lord George Paget, unaware that their General had retired from the field, were preparing to sell their lives dearly. There seemed little hope for them: they were a rabble, their horses worn out, many men wounded. Nevertheless, wheeling about, and jamming spurs into the exhausted horses, they charged the body of Russian Lancers who barred their retreat, 'as fast', wrote Lord George Paget, ' as our poor tired horses could carry us'. As the British approached, the Russians, who had been in close column across their path, threw back their right, thus presenting a sloping front, and, with the air of uncertainty Lord George had noticed earlier, stopped — did nothing. The British, at a distance of a horse's length only, were allowed to 'shuffle and edge away', brushing along the Russian front and parrying thrusts from Russian lances. Lord George said his sword crossed the end of lances three or four times, but all the Russians did was to jab at him. It seems probable that the Russians, having witnessed the destruction of the main body of the Light Brigade, were not greatly concerned with the handfuls of survivors. So, without the loss of a single man, 'and how I know not', wrote Lord George, the survivors of the 4th Light Dragoons and the 11th Hussars escaped once more, and began the painful retreat back up the valley.

One other small body of survivors had also been fighting beyond the guns. The 8th Hussars, restrained with an iron hand by their commanding officer, Colonel Shewell, had reached the battery in beautiful formation to find the 4th Light Dragoons had done their work and the guns were silenced. Colonel Shewell then led his men through the battery and halted on the other side, enquiring, like Lord George Paget,'Where is Lord Cardigan?' For about three minutes the 8th Hussars waited, then on the skyline appeared lances. The fifteen men of the 17th Lancers, who with the few survivors of the 13th Light Dragoons had charged out of the battery before the second line attacked, were now retreating, with a large Russian force in pursuit. Colonel Mayow, their leader, galloped up to Colonel Shewell. 'Where is Lord Cardigan?' he asked. At that moment Colonel Shewell turned his head and saw that he, too, was not only menaced in front: in his rear a large force of Russian cavalry had suddenly come up, and was preparing to cut off his retreat and the retreat of any other survivors of the Light Brigade who might still be alive beyond the guns. A stern, pious man, by no means popular with his troops,. Colonel Shewell had the harsh courage of Cromwell's Bible soldiers. Assuming command, he wheeled the little force into line and gave the order to charge. He himself, discarding his sword — he was a poor swordsman — gripped his reins in both hands, put down his head and rushed like a thunderbolt at the Russian commanding officer. The Russian stood his ground, but his horse flinched. Shewell burst through the gap and was carried through the ranks to the other side. Riding for their lives, his seventy-odd troopers dashed after him. The Russians were thrown into confusion and withdrew, and the way was clear.

But what was to be done next? Colonel Shewell paused. No supports were coming up, Lord Cardigan was not to be seen; there was nothing for it but retreat, and, just ahead of Lord George Paget and Colonel Douglas with the 4th Light Dragoons and the 11th Hussars, the other survivors of the Light Brigade began slowly and painfully to trail back up the valley.

Confusion was utter. No one knew what had taken place, who was alive or who was dead; no control existed; no one gave orders; no one knew what to do next. At the time when the survivors of the Light Brigade had begun to trail up the valley, Captain Lockwood, one of Lord Cardigan's three aides-de-camp, suddenly rode up to Lord Lucan.

'My lord, can you tell me where is Lord Cardigan?' he asked. Lord Lucan replied that Lord Cardigan had gone by some time ago, upon which Captain Lockwood, misunderstanding him, turned his horse's head, rode down into the valley and was never seen again.

The retreat, wrote Robert Portal, was worse than the advance. Men and horses were utterly exhausted and almost none was unhurt. Troopers who had become attached to their horses refused to leave them behind, and wounded and bleeding men staggered along, dragging with them wounded and bleeding beasts. Horses able to move were given up to wounded men; Major de Salis of the 8th Hussars retreated on foot, leading his horse with a wounded trooper in the saddle. All formation had been lost, and it was a rabble who limped painfully along. Mrs. Duberly on the heights saw scattered groups of men appearing at the end of the valley. 'What can those skirmishers be doing?' she asked. 'Good God! It is the Light Brigade!' The pace was heartbreakingly slow; most survivors were on foot; little groups of men dragged along step by step, leaning on each other. At first Russian Lancers made harassing attacks, swooping down, cutting off stragglers, and taking prisoners, but when the retreating force came under fire from the Causeway Heights the Russians sustained casualties from their own guns and were withdrawn. Nearly a mile had to be covered, every step under fire; but the fire came from one side only, and the straggling trail of men offered no such target as the brilliant squadrons in parade order which had earlier swept down the valley. The wreckage of men and horses was piteous. 'What a scene of havoc was this last mile — strewn with the dead and dying and all friends!' wrote Lord George Paget. Men recognised their comrades, 'some running, some limping, some crawling', saw horses in the trappings of their regiments 'in every position of agony struggling to get up, then floundering back again on their mutilated riders'. So, painfully, step by step, under heavy fire, the exhausted, bleeding remnants of the Light Brigade dragged themselves back to safety. As each group stumbled in, it was greeted with ringing cheers. Men ran down to meet their comrades and wrung them by the hand, as if they had struggled back from the depths of hell itself.

One of the last to return was Lord George Paget, and as he toiled up the slope

he was greeted by Lord Cardigan, 'riding composedly from the opposite direction'.

Lord George was extremely angry with Lord Cardigan; later he wrote an official

complaint of his conduct. He considered it was Lord Cardigan's 'bounden duty',

after strictly enjoining that Lord George should give, his best support — 'your

best support, mind' — to 'see him out of it'; instead of which Lord Cardigan

had disappeared, leaving his Brigade to its fate. 'Halloa, Lord Cardigan! were

you not there?' he said. 'Oh, wasn't I, though!' replied Lord Cardigan. 'Here,

Jenyns, did you not see me at the guns?' Captain Jenyns, one of the few survivors

of the 13th Light Dragoons, answered that he had: he had been very near Lord

Cardigan at the time when he entered the battery.

Out of this conversation, and a feeling that Lord Cardigan's desertion of his

brigade could not be reconciled with heroism, grew a legend that Lord Cardigan

never had taken part in the charge. During his life-time he was haunted by the

whisper, and as late as 1909 Wilfrid Scawen Blunt was told positively that 'Cardigan

was not in the charge at all, being all the time on board his yacht, and only

arrived on the field of battle as his regiment was on its way back from the

Valley of Death'.

When the last survivors had trailed in, the remnants of the Light Brigade re-formed on a slope looking southward over Balaclava. The charge had lasted twenty minutes from the moment the trumpet sounded the advance to the return of the last survivor. Lord Cardigan rode forward. 'Men, it is a mad-brained trick, but it is no fault of mine', he said in his loud, hoarse voice. A voice answered, 'Never mind, my lord; we are ready to go again', and the roll-call began, punctuated by the melancholy sound of pistol-shots as the farriers went round despatching ruined horses.

Some 700 horsemen had charged down the valley, and 195 had returned. The 17th Lancers was reduced to thirty-seven troopers, the 13th Light Dragoons could muster only two officers and eight mounted men; 500 horses had been killed.

Last modified 30 May 2002