This article has been peer-reviewed under the direction of Kristen Guest (University of Northern British Columbia) and Ronja Frank (Memorial University, St John's, Newfoundland). It forms part of the Equine Breed and the Making of Modern Identity project, funded by the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

orses were everywhere in Victorian Britain, visible and audible, in town and in country. Here is the poet W.E. Henley on being discharged from an Edinburgh hospital in the mid-1870s, free again to exult in the urban scene:

O, the wonder, the spell of the streets!

The stature and strength of the horses,

The rustle and echo of footfalls,

The flat roar and echo of wheels! [42]

Here, by way of contrast, is a much quieter, rural passage from Thomas Hardy's Far from the Madding Crowd (1874):

Inside the blue door, open half-way down, were to be seen at this time the backs and tails of half a dozen warm and contented horses standing in their stalls; and as thus viewed, they presented alternations of roan and bay, in shapes like a Moorish arch, the tail being a streak down the midst of each. Over these, and lost to the eye gazing in from the outer light, the mouths of the same animals could be heard busily sustaining the above-named warmth and plumpness by quantities of oats and hay. [121]

Both passages display an appreciative familiarity with the look and sound of horses, whether in street or in stable, and provide vivid evidence of a horse culture that was nearing its zenith. 1877 was, after all, the year of Anna Sewell's Black Beauty, the very well-informed protest on behalf of the modern horse that would lead to widespread humanitarian campaigns. The later nineteenth century also witnessed two scientific works that reflected an equally intimate knowledge of horses and their ways: Charles Darwin's The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals (1872) and Animal Intelligence (1882) by Darwin's protégé, C. J. Romanes. Both were attempts to develop a theory of "mental evolution" based on the idea that the inner life of animals developed alongside anatomical change, and that this could be deduced from their behaviour. Horses were vegetarians, they were more prey than predator, their essential passivity was balanced against their sporadic capacity for violence, their herd instinct made them dependent upon a leader, their ways had been co-opted and manipulated for human benefit for centuries. All of this made them obvious candidates for study.

In practice the theorists relied upon traditional ideas about the behaviour of horses, augmenting these with empirical evidence derived from anecdotes while offering new interpretations. The animals were said to possess resources that had never been properly acknowledged in earlier works such as William Youatt's The Horse. With A Treatise of Draught (1831, new edition 1843) and J. H. Walsh (Stonehenge) and I. J. Lupton's The Horse, in the Stable and the Field (1861). These were voluminous veterinary handbooks, well documented and detailed, by no means immune to animal suffering, but primarily aimed at horse-owners who needed to learn about their animals in order to care for them more effectively.

Clues to the primary concerns of Darwin and Romanes lay in the titles to their books: "intelligence" and "expression." "Intelligence" referred to patterns of reactive behaviour in animals that were strictly comparable to those well-known in human beings. "Expression" and "expressive" indicated a communicative impulse that went beyond the merely reactive, from which internal emotional states could be inferred. Following evolutionary principle, the mental processes of the different species not only needed to be compared with one another but with those possessed by human beings and to be described in similar ways. The divinely ordained subservience of animals to human needs, as Judeo-Christian Biblical tradition insisted, might to some degree remain in place, but with evolution the gap between "us" and "them" had undeniably become smaller, without ever closing entirely. Horses might remain intriguingly "other," but the similarities with humans had to be recognised and acted upon.

For instance, the horse's tendency to flee when confronted by any supposed threat was widely acknowledged as the most fundamental of its behavioural characteristics. If the animals were to serve humanity this obviously had to be curbed by training, a universal process over many cultures. For Romanes, though, it was remarkable for what it released. The horse is "subjected to various manipulations which, without necessarily causing pain, make the animal feel its helplessness and the mastery of the operator. The extraordinary fact is that, after having once felt this, the spirit or emotional life of the animal undergoes a complete and sudden change, so that having been "'wild' it becomes 'tame'" (329). Cruel only to be kind, the trainer forces the horse to undergo a "transformation" that will allow it to express more acceptable emotions when treated well. Romanes thought it important to stress that this revealed a capacity for affection towards humans as well as towards other horses (329-30).

The full gamut of equine emotion, as Darwin and Romanes claimed, was apparent in physical manifestations involving teeth, ears and the movement of eyes. Darwin recorded all manner of examples: "Horses when savage draw their ears close back, protrude their head, and partially uncover their incisor teeth, ready for biting. When inclined to kick behind, they generally, through habit, draw back their ears; and their eyes are turned backwards in a peculiar manner. When pleased, and when some coveted food is brought to them in a table, they raise and draw in their heads, prick their ears, and looking intently towards their friend, often whinny. Impatience is expressed by pawing the ground" (123). These were all "expressive" signs of intense feelings; even more important was the amount of anecdotal evidence which proved that horses possessed the faculty of memory, especially where previously travelled routes were concerned. This was significant because it showed that the animals could adapt to experience, a supreme mark of intelligence. Even more, it showed that they remembered their dealings with humans.

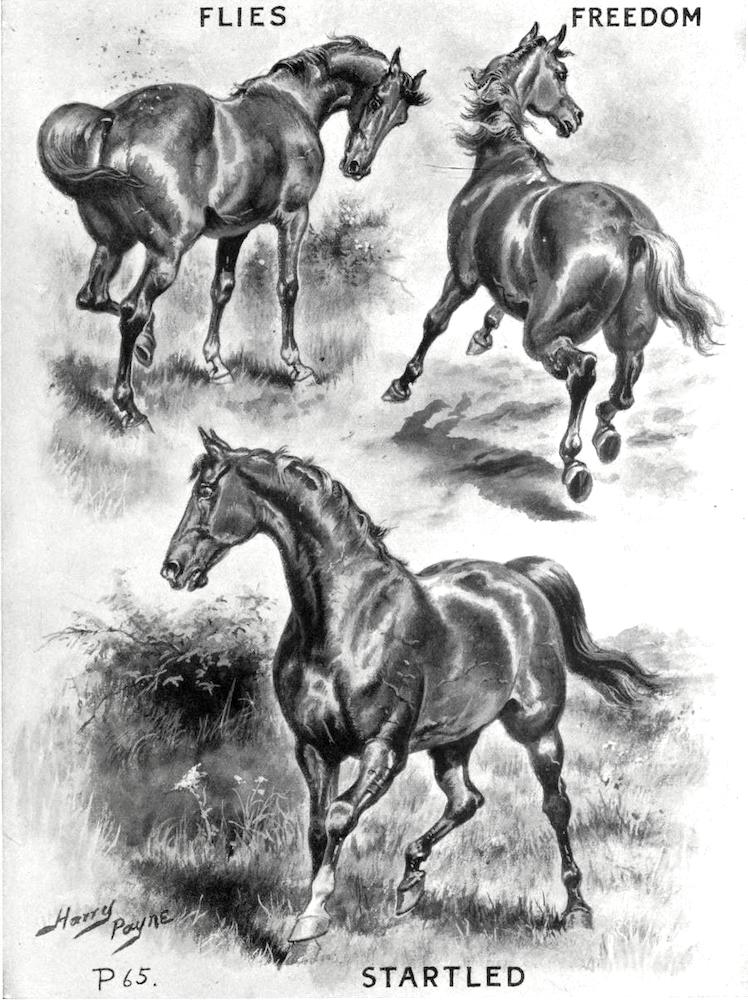

The behaviour of horses in Harry Payne's Flies – Freedom – Startled. Timmis, Plate 65.

The implications of these "evolutionary" discoveries were profound because they implied that the behaviour of such intelligent and expressive animals would inevitably reflect the personalities of the people around them. The possibility of interspecific interaction was certainly not lost upon Victorian novelists, who frequently drew upon the subject when they sought to indicate individual human qualities and to solicit recognition on the part of their readers. Although there is little concrete evidence that the theories about animal evolution put forward by Darwin and Romanes (or the criticism of their ideas led by the proto-behaviourist C. Lloyd Morgan) directly influenced the more intuitive ways in which late Victorian authors wrote about horses, it is nevertheless clear that equine behaviour was to be seen as reciprocal, as an indication of human sensitivity as well as that of the horse itself. Invariably, in the literature of the period, understanding the ways of horses, their "intelligence" however "expressed," and knowing how to live with them is the mark of someone who possesses a heightened awareness of the world they mutually inhabit. The true equestrian is exceptional – although he or she may not be able to enact their special vocation within their immediate circumstances. Anthropomorphic analogies between the lives of humans and the lives of horses are rarely complete.

Equine interventions in fiction might be passing reminders or they might occupy a discrete episode. Examples of both kinds can be found in, for example, the novels of George Eliot, Thomas Hardy and Henry James. More specifically, the ambiguities of training and taming carry over to gender relations, leading to the recurrent appearance of female characters whose prowess as horsewomen is an indication of their potential. Woman and horse are inextricably linked, and because the bond is physical in its manifestation it frequently provokes the erotic interest of a male observer. To consider just four examples: Dorothea Brooke, Bathsheba Everdene, Grace Melbury and Isabel Archer.

In the very early chapters of Middlemarch (1871-1872) we learn that "most men thought her bewitching when she was on horseback" (9-10). Yet we are also told that for Dorothea Brooke herself, "Riding was an indulgence which she allowed herself in spite of conscientious qualms; she felt that she enjoyed it in a pagan sensuous way, and always looked forward to renouncing it" (10). It may not be surprising, then, that when Sir James Chettam offers her a horse for hunting, she should decline the offer – "I mean to give up riding" (18) – nor that he should persist with "Every lady ought to be a perfect horsewoman, that she may accompany her husband" (22). To this Dorothea responds in turn "I have made up my mind that I ought not to be a perfect horsewoman, and so I should never correspond to your pattern of a lady" (22). This exchange is recalled much later on when Dorothea, by now committed to assisting Causabon's burdensome scholarship, protests, "but they don't understand – they want me to be a great deal on horseback, and have the garden altered and new conservatories, to fill up my days" (364). The implicit comparison is with Rosamond Vincy, whose horse (ridden against the advice of her doctor husband, Tertius Lydgate) takes fright, causing her to lose her baby. A wilful woman is matched by a wilful horse. Dorothea, again by contrast, is later seen as securely if unhappily contained as a passenger within her own coach (635-36). Eliot's narrative is deliberately ambivalent in the matter of women and horses: riding is both a socially conventional, and intellectually limited pastime and, at the same time, an undoubted skill requiring courage and intuition.

For Dorothea Brooke horse riding, although "pagan" and "sensuous," may have been an "indulgence"; for Bathsheba Everdene in Thomas Hardy's Far From the Madding Crowd the recreation is shown to be, although risky, personally and physically liberating. The passage describing her gymnastic display of oneness with a fellow creature, as secretly witnessed by the shepherd Gabriel Oak, is justly famous:

The performer seemed quite at home anywhere between a horse's head and its tail, and the necessity for this abnormal attitude having ceased with the passage of the plantation, she began to adopt another, even more obviously convenient than the first. She had no side-saddle, and it was very apparent that a firm seat upon the smooth leather beneath her was unattainable sideways. Springing to her accustomed perpendicular like a bowed sapling, and satisfying herself that nobody was in sight, she seated herself in the manner demanded by the saddle, though hardly expected of the woman, and trotted off …. [21-22.]

Again, there are comparisons to be made with male characters, with William Boldwood's carelessness with both women and horses and with his lack of empathy with his own expressive mount: "The horse bore him away, and the very step of the animal seemed significant of dogged despair" (235). Other men are equally self-revealing in their dealings with horses. The swordsman Sergeant Troy has a careless way with a whip (254) and ends up as a circus performer impersonating Dick Turpin, his horse a much-rehearsed version of the highwayman's Black Bess (331). It's the ever-dependable Gabriel Oak, Bathsheba's eventual partner, who is seen happily "mounted on a strong cob" (323).

Bathsheba Everdene and Farmer Boldwood — "I feel — almost — too much — to think," he said, by Helen Paterson Allingham, Far From the Madding Crowd.

Personality traits and gender relations are once again established through horsemanship in Hardy's subsequent novel The Woodlanders (1887), where one horse in particular shares endearing characteristics with her female owner. This is Darling, a mare twice described as "combining a perfect docility with an almost human intelligence" (190 and 202), whose outward demeanour will turn out to conceal a natural resourcefulness. Once more, inadequate men are shown up by their conduct on horseback. Dr. Edred Fitzpiers, Grace Melbury's husband, is a poor rider who usually needs to be accompanied. There are two exemplary incidents. In the first Fitzpiers takes out Dolly but falls asleep lying on her back. Luckily the horse, demonstrating the equine faculty of memory noted by Romanes returns him to the stable, preventing disaster. In the second, Fitzpiers, "a man ever unwitting in horseflesh" (235), when returning from his mistress, mounts the wrong horse, the far less manageable Blossom, who panics causing Fitzpiers to be thrown. This time he is rescued by Grace's father, who is riding Darling. The horses are contrasting examples of the two sides of equine nature, although they are content to walk home together, exhibiting the mutually affectionate behaviour valued by Darwin and Romanes. Hardy is nevertheless careful not to take the anthropomorphic possibilities much further; horses retain their animal identity; human beings are obliged to confront their social and sexual destiny.

Dorothea, Bathsheba and Grace are all on the brink of formal entry into the social world through marriage; their ease with horses hinting at an alternative, a freer, though still elusive way of life. Isabel Archer, Henry James's heroine in A Portrait of a Lady (1881), isn't given to riding, but early on at Gardencourt she "drove over the country in a phaeton." She "enjoyed it largely, and, handling the reins in a manner which approved itself to the groom as 'knowing,' was never weary of driving her uncle's capital horses through ending lanes and by-ways full of rural incident" (66). Following her marriage to Gilbert Osmund the freedom to follow her own inclinations cannot survive. Osmund, who cares more for insentient objects than living things, is firmly in the line of Hardy's men who are "ever unwitting in horseflesh." His sister, married to an Italian Count but with a poor social reputation and in many ways superficial, complains that her brother has let her animals suffer from neglect:

… I have always had good horses; whatever else I may have lacked, I have always managed that. My husband doesn't know much, but I think he does know a horse. In general the Italians don't, but my husband goes in, according to his poor light, for everything English. My horses are English – so it's all the greater pity they should be ruined. [267]

The Countess's concern for her horses provides a mildly comic but telling counterpoint to her humane attempts to protect her young niece from the devious schemes of her brother and his mistress. Here the interspecific analogy is lightly done, but unmistakably present nonetheless.

In the ever more self-conscious atmosphere of the fin-de-siècle the possibilities for equine identification shifted yet again. Following on from Black Beauty, there's a noticeable increase in moral sentiment, led by H. S. Salt, founder of the Humanitarian League in 1891, and bolstered by a greater sense of the psychology of all domestic animals. There are also changes in representation that reflect current social and political concerns: deepening public interest in questions of gender and sexuality, heightened social awareness driven by sociological enquiry and an overall feeling of it being a time of transition.

Abuse of horses continues to be linked with male despotism – the whip as a sexualised weapon. There's an example in one of the scandalous short stories of "George Egerton," who was closely associated with 'New Woman' writing, when the heroine, threatened by her male lover, witnesses his cruelty to his horses and then offers healing solace to the ill-treated animals (Keynotes, 142-3). The sexual implications of horsemanship are ever more present, too, in Hardy's penultimate novel, Tess of the D'Urbervilles (1891). When Alex D'Urberville, with Tess reluctantly beside him, embarks on a hazardous and intentionally menacing dog-cart gallop, "it was evident that the horse, whether of her own free will or of his (the latter being the more likely), knew so well the reckless performance expected of her that she hardly required a hint from behind" (58). For Tib, the "free will" of the human, specifically of the violent man, takes priority over whatever intelligence she may possess as a horse. As Alex boasts in the course of the ride: "Tib has killed one chap; and just after I bought her she nearly killed me…. And then, take my word for it, I nearly killed her. But she's touchy still, very touchy; and one's hardly safe behind her sometimes" (59-60). The moment is prophetic to the extent that Tess will have her own experience of forced submission when similarly abused by Alex – although that will hardly be the end of her developing human story.

Away from the hard-riding countryside the stresses and strains of crowded urban spaces result in a literature that views the city as simultaneously exhilarating and threatening, with the horse as its emblematic mascot. Here is W. E. Henley again, this time in the 1890s, celebrating the transforming power of sunlight on London life:

Gifting the long, lean, lanky street

With its abounding confluences of being

With aspects generous and bland;

Making a thousand harnesses to shine,

And every horse's coat so full of sheen

He looks new-tailored and every 'bus feels clean

And never a hansom but is worth the feeing; [1892-3]

This vision of a temporary horse heaven must, though, be compared with the more frequently recorded glimpses of horse hell.

Sometimes in the demanding modern world the horse suffers alone, beyond the reach of human pity; sometimes fiction appears to draw outright parallels with the limits of human endurance, at which point identification can be both indulged as a painful reminder and questioned as a delusion. Jasper Milvain, the desperately ambitious journalist in George Gissing's New Grub Street (1891), contemplates a "poor worn-out beast" in a field neighbouring his home: "All skin and bone, which had presumably been sent here in the hope that a little more labour might still be exacted from it if it were suffered to repose for a few weeks. There were sores upon it back and legs; it stood in a fixed attitude of despondency, just flicking away troublesome flies with its grizzled tail" (34). Yet Milvain resists the mirror image: a victim of commercial exploitation is precisely what he is determined never to become. There are, though, peripheral characters in the novel, fellow writers struggling in the marketplace, with whom the reader might well associate this deceptively placed picture of a worn-out cab horse.

The realms of human and animal suffering in the workplace may intersect, but they are not necessarily identical. To return to Hardy's Tess, there's an instructive parallel to be drawn with the physical condition and ultimate death of Prince, the much-loved horse belonging to the Durbeyfield family. Prince, though ancient and "rickety" (35), is a "bread winner" (40); though never given a personality as such, his expressive intelligence is well-attested. Woken in the middle of the night to go on an unexpected journey, he "looked wonderingly around… as if he could not believe that at that hour, when every living thing was intended to be in shelter and at rest, he was called upon to go out and labour" (35-6). Prince will die when an early morning mail cart crashes into the loaded wagon with Tess at the reins, her mind elsewhere, its shaft puncturing his chest: "his life's blood… spouting in a stream, and falling with a hiss into the road" (38).

In stagnant blackness they waited through an interval which seemed endless. Illustration to Thomas Hardy's Tess of the D'Urbervilles by D. A. Wehrschmidt.

The amount of feeling that Hardy manages to compact into the moment when Prince's body becomes a quasi-religious spectacle is extraordinary. The flood of coagulating blood that splashes onto Tess's body as she places her hand on the wound of her co-worker joins human and non-human in their shared mortality, leading her to regard herself, in a self-condemning and grotesquely misplaced word, as a "murderess" (40). Certainly, the bond that Tess and her family have with Prince has the air of tragedy, his equine stoicism ratified by his death and deserving of the near-human funeral that they provide for him. As an example of anthropomorphic pathos this could hardly be more powerful – all the more anguished in that neither human nor animal fully comprehend their situation. The death of Prince places them both within the unforgiving context of rural labour. Alex's patronising gift of an unnamed cob to the Durbeyfields as a replacement will be little more than a sexual bribe (80), and this "second horse" will, in turn, have to be sold out of necessity (276). Yet, within the novel as a whole, the death of Prince in a very early chapter only partly foreshadows what lies ahead for Tess. The work horse dies in harness; Tess will fight on alone and grow in understanding.

In the course of the long nineteenth century the working habits that humans shared with horses underwent continual change, partly through the extended coming of mechanisation. At what point, in purely literary terms, did the horse retreat from being a universal if often unremarked presence, to occupying a more marginal and more symbolic role? Obviously, that process, which has been comprehensively explored by Ulrich Raulff, was never fully completed – and it still has far to go today – but (if we put the military horse to one side) literary appreciation of the horse as a daily companion becomes less common while changes in farming practice reinforce a complex form of nostalgia. A.E. Housman's poem about a dead ploughboy in A Shropshire Lad (1896) can be heard as the late affirmation of pastoral tradition, the recognition of an ancient, enduring and arduous way of life:

Is my team ploughing,

That was I used to drive

And hear the harness jingle

When I was man alive?

Ay, the horses trample

The harness jingles now;

No change though you lie under

The land you used to plough. [35]

Housman's elegy is just one of a number of late Victorian literary works that tell, if only incidentally, of the everchanging appreciation of horses. They include George Moore's Esther Waters (1894), poems by Rudyard Kipling, even Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897), where the screams of tormented horses are even louder than those of tortured humans. As they entered the twentieth century, writers continued to appeal to the interdependence of species, not only aware that horses shared overlapping spaces within a socially structured whole, but that, despite being "other," they might actually possess the expressive intelligence claimed by evolutionary theory.

Bibliography

Akilli, Sinan. "The Agency and the Matter of the Dead Horse in the Victorian Novel." In Equestrian Cultures. Horses, Human Society, and the Discourse of Modernity, Edited by Kristen Guest and Monica Mattfeld, 39-53. Chicago and London: The University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Chamberlin, J. Edward. Horse: How the Horse has Shaped Civilisation. Toronto: Alfred A. Knopf, 2006.

Darwin, Charles. The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. (1872, 1890 edition). Edited by Joe Cain and Sharon Messenger with an introduction by Joe Cain. London: Penguin Classics, 2009.

Dorré, Gina M. Victorian Fiction and the Cult of the Horse. London: Routledge, 2006.

Eliot, George. Middlemarch. (1871-2). Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Rosemary Ashton. London: Penguin, 1994.

Egerton, George. Keynotes & Discords. London: Virago, 1983 (1893 and 1894).

Forrest, Susanna. The Age of the Horse: An Equine Journey through Human History. London: Atlantic, 2016.

Gissing, George. New Grub Street. (1891). Edited with an Introduction and Notes by John Goode. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 1998.

Gordon, William J. The Horse-World of London. London: The Religious Tract Society, 1893, reprinted Newton Abbot, Devon: David & Charles (Publishers) Ltd, 1971.

Hardy, Thomas. Far from the Madding Crowd. (1874). Edited with Notes by Suzanne B. Falck-YI and with a new Introduction by Linda M. Shires. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 2002.

Hardy, Thomas. The Woodlanders. (1887). Edited by Dale Kramer. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1981.

Hardy, Thomas. Tess of the D'Ubervilles. (1891). Edited by Juliet Grindle and Simon Gatrell with a new Introduction by Penny Boumelha and Notes by Nancy Barrineau. Oxford: Oxford World's Classics, 2005.

Henley, W.G. Poems. London: David Nutt, 1898.

Housman, A.E. Shropshire Lad. (1896). Edited by Archie Burnett with an Introduction by Nick Laird. London: Penguin, 2010.

James, Henry. The Portrait of a Lady. (1882). Edited with an Introduction and Notes by Philp Horne. London: Penguin, 2011.

Kean, Hilda. Animal Rights: Political and Social Change in Britain since 1800. London: Reaktion, 1998.

McShane, Clay and Joel A. Tarr. The Horse in the City. Living Machines in the Nineteenth Century. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2007.

Moore, George. Esther Waters: An English Story. London: Walter Scott Ltd, 1894.

Raulff, Ulrich. Farewell to the Horse. The Final Century of Our Relationship. London etc: Penguin Books, 2018.

Rees, Lucy. The Horse's Mind. London: Stanley Paul, 1984.

Ritvo, Harriet. The Animal Estate: The English and Other Creatures in the Victorian Age. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1987.

Romanes, C. J. Animal Intelligence. London: Routledge, Kegan Paul, 1882.

Timmis, R. S. Modern Horse Management. London: Cassell and Co., 1915. Biodiversity Heritage Library, from a copy in the Webster Family Library of Veterinary Medicine. Web. 13 March 2025.

Walker, Elaine. Horse. London: Reaktion, 2008.

Walsh, J.H. The Horse, in the stable and the field: his varieties, management in health and disease, anatomy, physiology, etc. London: Routledge, Warne and Routledge, 1861.

Ward, Neil. Horses, Power and Place. A More-Than-Human Geography of Equine Britain. London and New York: Routledge, 2024.

Wood, Rev. J. G. Horse and Man: Their Mutual Dependence and Duties. London: Longmans, Green, and Co., 1885.

Youatt, William. The Horse: With A Treatise of Draught. London: Chapman and Hall, 1831, Revised 1843.

Youatt, William. The Obligation and Extent of Humanity to Brutes; principally considered with reference to the domesticated animals. London: Longman, Orme, Brown, Green, and Longman, 1839.

Created 22 April 2025