Cover of the book under review [Click on this and following images for larger pictures, and sometimes for commentaries by Philip Allingham. Captions are provided by the author. The sources of the images are given either at the end, or on the linked pages. The book itself is not illustrated.]

Some of the best-known figures in Victorian literature behave in a manner quite at odds with their biological age. In this wide-ranging book, Claudia Nelson explores this intriguing phenomenon. Selecting relevant examples from diverse sources, she analyses their characters and roles, showing how age inversion works in the novel and on us, and how it relates to and reflects upon the life and thought of the time. No one could be more qualified for the task: Nelson is a well-known scholar in the field of childhood in literature, with several of her own writings listed in her "Works Cited," one of them (Boys Will Be Girls, 1991) a seminal work focusing on gender inversion in Victorian children's literature. With such a variety of material, it is not easy for her to pin down the phenomenon, and her categories tend to overlap. But the resultant study is valuable precisely for its crossing of borders, as well as for its many subtle readings, incidental insights, and wider implications.

Nelson's introduction reminds us of the Victorians' fascination with childhood, and the ways in which it was linked with old age in their literature. The introduction also sets out the general observations she plans to examine more closely (an apparent rise in the number of "child-men" during the period, for instance), and provides brief summaries of each chapter — necessary guidance when some of the material is appropriate to more than one of them.

"The Old-Fashioned Child and the Uncanny Double"

In the first of the five main chapters, Nelson looks at those child characters who, for one reason or another, seem preternaturally aged. Starting with one of the most obvious cases, Dickens's Paul Dombey, she takes her cue from Freud's 1919 essay on the "Uncanny," seeing Paul's father as his double, and quoting to good effect the passage in Chapter 8 in which Dickens describes the two sitting by the fire:

They were the strangest pair at such a time that ever firelight shone upon. Mr Dombey so erect and solemn, gazing at the blare; his little image, with an old, old face, peering into the red perspective with the fixed and rapt attention of a sage. Mr Dombey entertaining complicated worldly schemes and plans; the little image entertaining Heaven knows what wild fancies, half-formed thoughts, and wandering speculations. Mr Dombey stiff with starch and arrogance; the little image by inheritance, and in unconscious imitation. The two so very much alike, and yet so monstrously contrasted.

Quoting from Freud's essay on the "The Uncanny," Nelson finds this an example of the "doubling, dividing and interchanging of the self ... the repetition of the same features or character-traits" and so on across generations (16). Such a reading certainly helps to explain Paul's "'monstrous' old-fashionedness," and why he is "sly and goblin-like" as well as sympathetic (17, 18). He represents, says Nelson, "an innocence so imbricated with its own opposite that its possessor cannot live" (!8). Partly contemporary with Dickens, Freud provides her with a better theoretical basis here than, say, the Swiss psychoanalyst Alice Miller, whose ideas inform Gerhard Joseph's similar reading of the father and son's "pathology" (see 182, n.7).

Left to right: (a) Chris in the background as the children prepare their gardening project in Juliana Ewing's Mary's Meadow (illustration by Harley, facing p.41). He holds aloft like a crown the bonnet his older sister Mary has made for their sister's role as "Weeding Woman," but has been wearing herself — it was a role Mary would have relished, but has selflessly renounced. Instead she willl be "Traveller's Joy." (b) Sara Crewe in Francis Hodgson Burnett's A Little Princess, "a child full of imaginings and whimsical thoughts" (illustration by Ethel Franklin Betts, facing p. 16). (c) Sara with one of her doubles, the beggar girl Anne (illustration by Betts, facing p.168).

As so many critics have noted, such characters were freighted with meaning, and meaning that is absolutely central to the works in which they appear. Nelson finds feminist ideas in much of her material. In stories like Jeanie Hering's Elf (1887), also considered in Chapter 1, these ideas can hardly be missed: the eponymous heroine here emerges successfully from the shadow of her "custodial grandfather" (24) with the help of a female role model, shedding her quaintness in the process. (This summary does no justice to the subtleties of Nelson's reading.) Less obvious though is the feminist thread in another case of an "old-fashioned" child, Lionel Valliscourt in Marie Corelli's best-seller The Mighty Atom (1896). Victim of the secular education provided by his atheistic father, Lionel commits suicide as a way of facing his uncertainities. Here, Nelson links the child convincingly to his "transgressive mother" (31), and finds his death "in one sense a feminist statement, a misguided but understandable response to the real social problem of upper-class male dominance" (32). Age-inverted figures, she shows, can comment on other ideologies as well. Juliana Ewing's children's novella Mary's Meadow (1883-84), in which encephaletic Chris helps "colonise" a disputed meadow with flowers, and win it from the local Squire, can be read, she agrees, as a comment on imperialism — though she points out that it is not at all a straightforward one, and situates anxieties about it in Chris himself. Similar complexity is found in Francis Hodgson Burnett's popular A Little Princess, where the "old-fashioned child" undergoes changes of fortune that bring class and other issues into the picture. In this case, the child is able to rise above them by using her imagination. These opening discussions make it clear that precocity is "a response to adult needs and behaviors rather than an expression of the intrinsic nature of the child in question" (156), and also that the child thus delineated is a vehicle for the authors' concerns about those "needs and behaviours."

"The Arrested Child-Man and Social Threat"

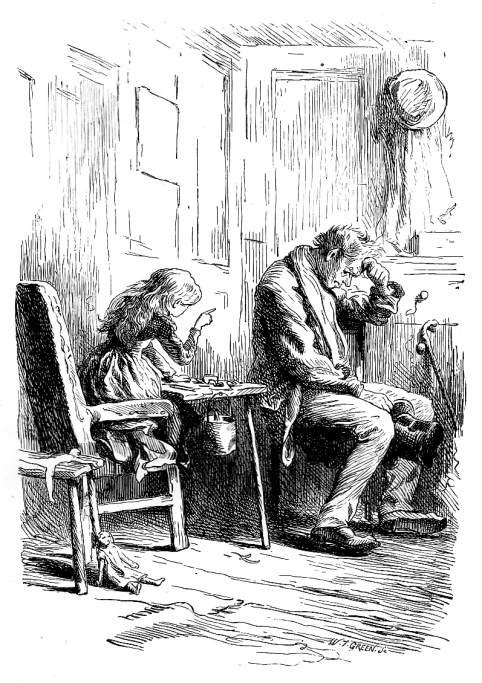

Jenny Wren reproving her alcoholic father in Our Mutual Friend.

The title of Chapter 2 is more dramatic. Subjects again range from the predictable (such as Harold Skimpole in Bleak House, and Jenny Wren's father in Our Mutual Friend) to the unexpected (such as the ruthless pygmy Tonga in Arthur Conan Doyle's The Sign of Four and even Kurtz in Conrad's Heart of Darkness, found crawling on hands and knees towards the bush by the horrified Marlow). Simple, other-worldly child-men like Dickens's Mr. Dick in David Copperfield might be looked at askance by others in their narratives, but, by and large, Nelson sees them as providing a reproach to corrupt adult society. Primitives like Tonga, on the other hand, pose the "social threat" of this chapter's title. Horror fiction provides the ultimate expression of this. Nelson has already shown in Chapter 1 how often "old-fashioned" child figures have "doubles" of some kind. Bringing these to the fore again, she looks at perhaps the most famous doubles of all, seeing Hyde as the "child-man" hidden in R. L. Stevenson's Dr Jekyll. Finding that such uninhibited, unconstrained figures provoke "a touch of envy" (70), she associates them with the discourse about natural instinct, and the whys, wherefores, and consequences of its frustration in Victorian society. Although sometimes disconcerting, the linking of characters from standard texts, children's stories and popular fiction is also stimulating.

"Women as Girls" and "Girls as Women"

Left to right: (a) The girlish Dora before marriage, paying more attention to her flowers than her suitor, as David Copperfield gazes at her yearningly. (b) Little Nell, a child doomed to bear the burden of her irresponsible grandfather, and to die as a sacrifice to him. (c) Amy Dorrit clinging to her father in Little Dorrit, where again both are age-inverted subjects.

These two chapters (3 and 4), with their complementary discussions, also deal with gender — Nelson's forte. As before, Dickens features more prominently than other canonical authors, with Dora Copperfield leading in the procession of child-women in Chapter 3, and the Infant Phenomenon from Nicholas Nickleby and Little Nell from The Old Curiosity Shop putting in appearances later, the latter very briefly; while Chapter 4 analyses heroines like Esher Summerson in Bleak House and Amy Dorrit in Little Dorrit, adolescents whose circumstances have brought them responsibilities beyond their years. The Brontës and Thackeray put in brief appearances too, with Nelson showing how little Paulina from Villette manages to be simultaneously daughter and wife, and (acutely) how Thackeray manipulates our response to that "precocious daughter" Becky Sharp (122), by undermining the grief she feels after her father's death.

Two illustrations from Diana Mulock's Olive, by the illustrator G. Bowers. Left to right: The eponymous heroine, walking in her favourite meadow, is stooped because of a congenital curvature of the spine, and looks prematurely old. (b) Olive with her future husband Harold, who has just rescued her from a fire. Her touch of deformity now makes her look girlishly petite (Ch. 46), and indeed she will act girlishly with Harold too.

But most examples are again drawn from other sources. One such is Dinah Mulock's eponymous heroine in Olive (1850). A child who has been "less a child than a woman dwarfed into childhood and older than her age" (qtd. 79; Mulock, Ch. 5), but who becomes a diminutive adult who clings girlishly to her beloved Harold, she fits both categories of age inversion. Another eponymous heroine, Rider Haggard's in Ayesha (the sequel to She) has even more aspects, as "a manifestation of the Triple Goddess: mother, maiden and crone in one" (90). All fascinating stuff, especially when examined, as here, in light of Victorian anthropology, sexology (Havelock Ellis) and, in the case of H. G. Wells's Weena in The Time Machine, Darwinism — or, rather, its inverse. One or two of the children's works discussed by Nelson seem to sink under the weight of critical debate, but this is not the case with Wells, and it is good to see him included here.

"Boys as Men"

The Artful Dodger in his oversized men's clothes, as illustrated by James Mahoney (Dickens 30).

Age inversion in female characters has much to do with money, or the lack of it: the poverty-stricken girl must take on family responsibilities, caring for her siblings or even her parents, while her better-off counterpart can afford to depend on the breadwinner, whether father or, later, husband. Returning to men again in Chapter 5, Nelson focuses on financial matters. Her interest here is not on strangely old-fashioned or old-looking children, who could be of either sex, but with boys who act like men, typically if not invariably for gain. As so often, Dickens provides a starting-point, with the top-hatted Artful Dodger and his fellow pickpockets in Oliver Twist, and Bart Smallweed in Bleak House, the latter

a weird changeling to whom years are nothing. He stands precociously possessed of centuries of owlish wisdom. If he ever lay in a cradle, it seems as if he must have lain there in a tail-coat. He has an old, old eye, has Smallweed; and he drinks and smokes in a monkeyish way; and his neck is stiff in his collar; and he is never to be taken in; and he knows all about it, whatever it is. In short, in his bringing up he has been so nursed by Law and Equity that he has become a kind of fossil imp. (Chapter 20)

Then there are what Nelson calls, when summarising the chapter in her introduction, "the heroic or the mock-heroic" (20). Two pairs of contrasting boy-men and men-boys — David Balfour and Alan Breck Stewart in Stevenson's Kidnapped, and the father and son who change places in Thomas Anstey' s ever-popular comic Vice Versa, demonstrate the importance of economic issues, and of readjusting our own values. Pairing can obviously be as effective a technique as doubling, pointing up contrasts and suggesting ways in which a better balance can be achieved in adult life. But alternatives are not always offered. Nelson's last sub-heading in this chapter is "Tragic Precocity at the Turn of the Century," and here, dealing with Hardy's "Little Father Time" in Jude the Obscure amongst others, she finds that as time goes by growing boys are even more radically affected than their sisters by the social norm — in their case, by the pressure to become providers. Young Time famously relieves his family of its economic burden in the only way currently within his power, by hanging his two half-siblings and then himself.

Conclusion

Finally, picking up the idea of readjusting values, Nelson turns the spotlight on the reader in her conclusion — to be precise, on "The Adult Reader as Child." This allows her to press the claims of children's writers to be taken more seriously, by demonstrating that some, like Anstey and (here) Florence Montgomery and George MacDonald, establish a construct of childhood which they invite the adult reader to enter and become "resocialised" through. No one was more influential in this respect than Samuel Smiles, whose immensely successful Self-Help is also considered here, on the grounds that it shrewdly adapted "the techniques of the children's literature of Smiles's youth" in order to influence and empower his readership (170). Again, a perceptive and sometimes surprising (and therefore refreshing) choice of material.

The 1840s, just before the period dealt with here, had produced what Sally Shuttleworth calls "an extraordinary flowering of the literature of child development" (2), and there was extensive cross-fertilisation in this area between the scientists and the creative writers. To use a pair of examples of my own, George Meredith was much influenced by the developmental ideas of Herbert Spencer when writing about the stages of his hero's development in The Ordeal of Richard Feverel in the late 1850s. It must have seemed all the more transgressive now to produce characters who, like that "fossil imp" Bart Smallweed, departed so completely from the norm. But Nelson has clearly succeeded in one of her aims, that of showing that "the idea of age as a construct, something separable from biological condition" (179) was accepted, by writers and readers alike.

It would seem, from many of the figures discussed here, that writers used age inversion primarily as a technique, often to convey criticism of society and urge a change of heart or behaviour, generally but by no means always towards children themselves. Nelson would like us to see it as much more than a ploy, though — as a way of opening windows on conflicts at the very heart of the age, between "respect for history and heritage on the one hand and for innovation, progress, vitality and newness on the other" (180). Age, she believes, joins gender and other major issues of the day as a subject on which the period was multivocal, and she prompts us to pay more attention to the different approaches to it, and the complexities that arise from them. The chief value of her study is probably in its insights into individual texts, which will be of great interest to children's literature specialists and Dickens scholars in particular. But it is well worth considering these larger implications, and Victorianists in general will find the book both richly informative and thought-provoking.

Book under review:

Nelson, Claudia. Precocious Children & Childish Adults: Age Inversion in Victorian Literature. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2012. 211pp. ISBN 13: 978-1-4214-0534-6 / ISBN 10: 1-4214-0534-2. £24.70.

Other references and sources of illustrations:

Burnett, Francis Hodgson. A Little Princess, being the whole story of Sara Crewe now told for the very first time (1905). New York: Scribner's, 1917. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2012.

Dickens, Charles. Oliver Twist. New York: Harper, 1872. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2012.

Ewing, Juliana. Mary's Meadow. Boston: Little, Brown, 1900. Internet Archive. Web. 1 September 2012.

Mulock, Dinah. Olive. New York: Harper, 1872. Project Gutenberg. Web. 1 September 2012.

Shuttleworth, Sally. The Mind of the Child: Child Development in Literature, Science and Medicine, 1840-1900. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Last modified1 September 2012