This review is adapted from one originally published under the title of "When Words Moved Fast: The Late Victorian Network of Ideas" in the Times Literary Supplement of 27 March 2020. Page numbers, illustrations, captions and links have been added: click on the images to enlarge them, and for more information about the two paintings featured.

The 1880s have never had much of a chance beside the risqué 90s. In The Victorian Temper (1952), the early Victorianist, Jerome Buckley, found them superficial and uninspiring, summed up not in a literary work or movement, but in the paintings of James Abbott McNeill Whistler. Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s duly features Whistler's Nocturne in Black and Gold, the Falling Rocket on the front cover, as editors Penny Fielding and Andrew Taylor set out to prove that Buckley was as wrong about the literature of the decade as he was about the artist. The cover of Richard Menke's Literature, Print Culture and Media Technologies, 1880-1890 is equally dynamic: it features the celebrated photograph of technophile Mark Twain holding a shining light-globe, with Nikolas Tesla looking on in the background. Menke ranges from one side of the pond to the other, but his agenda is more specialised than Fielding and Taylor's — to throw light on how the "media proliferation" of the time (phonograph, telegraph, telephone and others) affected the period's print culture, including the writing, production and consumption of books.

For all their different parameters, the ground covered in these two studies sometimes overlaps. Both treat their chosen decades as times of transition, when (for example) individual consciousness was stretched and strained as global communications advanced, when information technology began to impact society and authorship, and when networking became at once less serendipitous and more powerful in its effects. Between them, they present the 1880s as a period crackling with new tensions and possibilities.

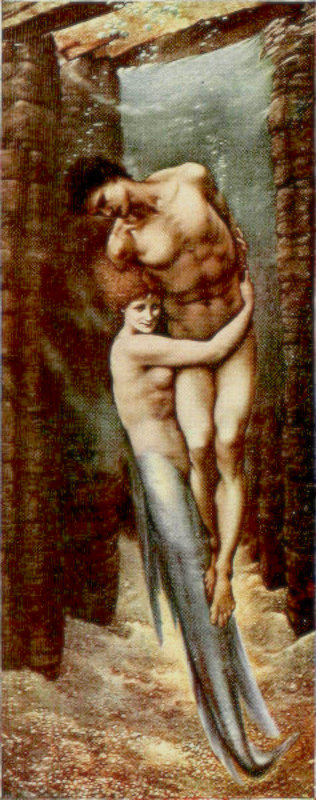

In their introduction, Fielding and Taylor ask: "What happens when we look at a decade that has been neglected in favour of the more seemingly dominant 1890s?" (2). One answer is that closer inspection yields new entries to it. Claire Pettitt's opening chapter ("Mermaids Amongst the Cables") looks beyond the traditional cultural context, to see how both artists and writers responded to emerging technologies and the recent broadening of scientific knowledge — specifically, the spread of underwater telegraph cables, the consequent discovery of exotic forms of sea-life, and the wider effects of this new form of communication. Pettitt analyses two paintings, Evelyn De Morgan's The Sea Maidens and Edward Burne-Jones's The Depth of the Sea, both exhibited in 1886, and showing (respectively) a broken chain of mermaids linking hands in the sea, and a drowned man being dragged to the seabed in the tight embrace of a mermaid. To Pettitt, these efforts to embody "the hidden matter of the media" suggest the artists' fears for humanity on the brink of this brave new connected world, as well as their fascination with it. What will happen to the human element here?

Left: Evelyn De Morgan's The Sea Maidens. Right: Sir Edward Burne-Jones's The Depth of the Sea.

The question recurs in Pettitt's equally striking examination of Swinburne's Century of Roundels, also dating from 1883, which shows how the roundels' complexities, repetitions and small variations of sound, rhythm and sequencing function like digital coding, to convey the poet's unique flow of creative energy, remaining medium rather than meaning. The full implications of Pettitt's approach become clear at the end of the chapter, when she questions the impact of the disembodied processing and transmission of information on both politics and the individual. Here she mentions the "Bloody Sunday" protest of 1887 in Trafalgar Square, which ended in carnage. This protest is analysed by John Stokes in a later chapter, "Public Spectacle in 1887"; what it exemplifies for Pettitt is simply, and presciently, the violent "abstraction" of the physical being (28), the alienation and disavowal of the "individual subject or citizen" (29) whose own meaning seemed under threat in this new age.

Words travelled fast now; so did literary forms. But there was a return to an older tradition as well as breaks with it. Linda K. Hughes takes up the 80s' rather curious vogue for early French verse-forms, and the shared transatlantic interest in their revival — noting that Austin Dobson's Vignettes in Rhyme and Other Verses (1880) came out first in America, and that these short, tight forms were ideally suited to the periodicals circulating on both sides of the pond. As if to address the problem of the individual's worth and the individual voice, Hughes pays attention here to women writers like Amy Levy, who used such forms for their own very present and subversive purposes. Levy's remarkably prophetic "Ballad of Religion and Marriage," in which she foresees that one day "Folk shall be neither pairs nor odd," and marriage and faith will both become obsolete, was too daring to be published in her own lifetime. But Levy and the other women poets who adopted this form did contribute, as boldly as they could, to the changing discourse on gender and other issues of the day. In this respect, they were moving on, rather than back. Later on, Fielding refers to Levy in her own chapter, about the so-called "minor poetry" of the time ("The Time of W.E. Henley: 'Minor Poetry' and the 1880s"). There, she shows how consciously Levy rejected the sage's stance in favour of the kind of "passionately subjective" poetry of the eighteenth-century poet, James Thomson (82). Others, moving in the same direction, adopted a similar approach. Fielding's close, sensitive reading of excerpts from Henley's "In Hospital" sequence, published in book form in 1888, avoids associating him too closely with modernism, but goes a long way towards placing the decade on the literary roadmap which does, in the end, lead to aestheticism and beyond.

Far from being insubstantial, this was a decade of great change. It was bound to be: W. E. Forster's Education Act of 1870 was already having its effect on the literary marketplace. As literacy spread, the demand for pacey adventure stories, as well as pithier forms of verse, grew. Gripping yarns like Robert Louis Stevenson's and Rider Haggard's became popular, and the hefty three-volume novel tipped into terminal decline. Menke, in his brilliant chapter on "Format Wars," is very good on the contributory causes of this, and its effects strike a chord even now: "later in the century," he says, "an interest in lightness or craftedness in aesthetics coincided with an acceptance of the kind of punctuated attention suited to briefer reading, the kind of reading that might be done on public transport or between tasks" (105-6). Yet some of the new enthusiasts took their reading more seriously than that implies, as Angela Dunstan points out her contribution to Fielding and Taylor's collection, "The Newest Culte': Victorian Poetry and the Literary Societies". The democratisation of the reading public led to a widespread taste for analysing and judging literature, and, even more importantly, to valuing the individual response to it. Dunstan suggests that by privileging this response (just as Levy privileged personal feelings over received wisdom), readers were helping to offset the flattening effects of mass communication and develop their own sensibilities. Here is another way in which the 1880s looked forward to the next century.

Complementing each other again, both these books deal with the kind of networking that went on long before the arrival of the web. The most striking example was the amazingly prolific and influential Scottish writer, Andrew Lang. Best known as a collector of fairy-tales, Lang was much more than that: a networker incarnate, and an ideal subject for those currently applying the ideas of relational sociology to the literary scene. Fielding and Taylor include a chapter by Nathan K. Hensley on "Network, History, Method: Andrew Lang in and after the 1880s"; later in the collection, Sara Lodge shows Lang in operation in "He and She: The 1880s, Camp Aesthetics and the Literary Magazine," subtly drawing out the conscious and subconscious reasons for the exclusively male nature of this networking. Menke, for his part, comes to Lang in his chapter on "The Unmediated Novel," through discussing Marie Corelli's The Sorrows of Satan (1895). Here, one struggling author, albeit male, falls prey to the kind of "system" that Lang runs; another, a woman who writes romantic novels, bypasses it by appealing to her audience directly. Few people outside academe will have read the novel, but Menke's point will not be lost on his wider audience: Lang features as the Scotsman David McWhing, who has "his finger in every pie" (121), and Corelli's bitterness about him is unmistakeable. At the end of this chapter, Menke shows how George Paton, aka Emily Morse Symonds, made the system itself her subject in A Writer of Books (1898), and then turned to writing non-fiction. This illustrates all too well his own disturbing words at the end of this chapter, which embody the same kind of fears that Pettitt expresses in Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s: "what remains after the loss of material media in all their distinctness is information" (136).

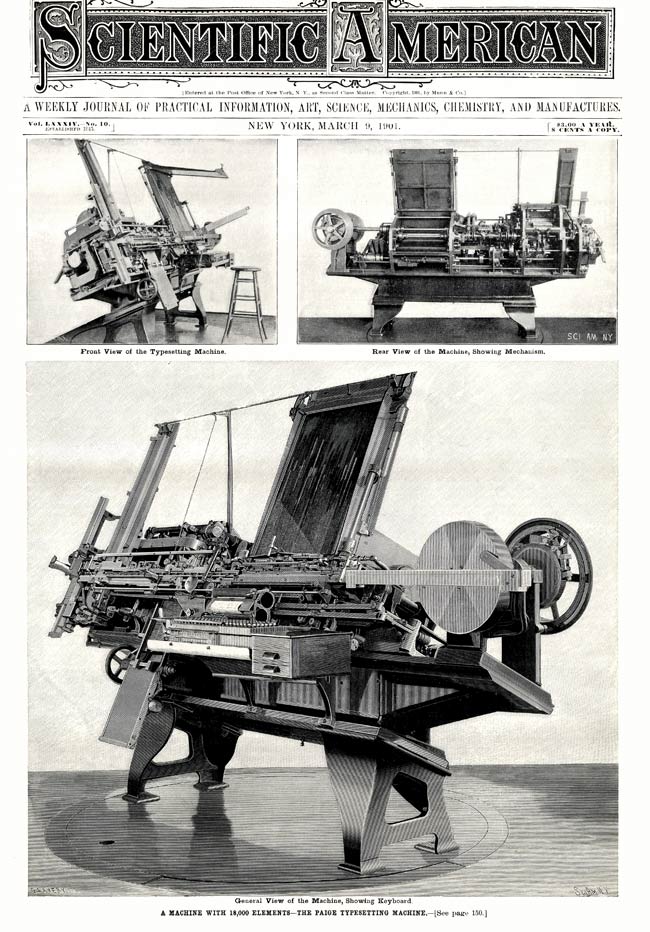

As Menke moves into the 1890s, beyond the self-appointed (though not overly strict) limits of Fielding and Taylor's book, he finds the means of technological communication multiplying dizzyingly, and interacting with one another. In short, it does become more like the information-based system we know today. In 1895, in the very throes of writing Dracula, Bram Stoker was recruited by Mark Twain to invest in the cumbersome Paige Compositor — "an entire printshop on a camshaft" (176). Although the project spelled financial ruin for Twain, both writers' interest in technology proved fruitful.

The Paige Compositor seen from different angles

on the front cover of the Scientific American

in March 1901, in the Internet Archive.

Stoker drew usefully on this development in Dracula, which is, as Menke says, a veritable "mosaic" of fictional records purporting to produce not simply a narrative but factual, verifiable knowledge (45). That, of course, produces huge tension, because Stoker's other main inspiration, which these records were intended to convey, was the occult — the ultimately unverifiable.

Here then was another feature of the decade, strangely intertwined with technological advances. The role of the occult in Victorian culture has long interested Menke, who discussed instances of it in his book on Telegraphic Realism: Victorian Fiction and Other Information Systems (2008). In Dracula, the new media rise splendidly to the challenge of reporting on the vampiric anti-hero and his doings; but their very capabilities are proved at the cost of their credibility. Menke puts it like this: "The occulting of media translation allows late nineteenth-century culture to use its vaunted technological advance in a paradoxical way: to create a template for representing the mystical and supernatural, the imperfectly knowable" (144).

Two points here are of special interest. First, the methodology. This is not so much because of the self-consciousness of the process, since earlier gothic novelists also very deliberately married their sensationalism with claims to realism. It was expected of them: a publisher in Corelli's The Sorrows of Satan advises one of the aspiring authors, "What goes down ... is a bit of sensational realism told in terse newspaper English" (qtd. in Menke 116). Rather, Menke argues, it is the thoroughness with which all the pieces of information, however extraordinary, are given their own "fictional metadata pointing to their sources, tags identifying their dates and a riot of 1890s media" (138). There is a jostling for space and influence here that is very much of our own times. Then, there is the matter of trust, even in what appear to be such impeccable sources. At the end of Dracula, Jonathan Harker admits, "in all the mass of material of which the record is composed,there is hardly one authentic document" (qtd. in Menke 145). Menke says he has "tried to avoid making simplistic claims about the relationships between the media systems of the late nineteenth century and the twenty–first" (156), but the connections are surely inescapable.

Menke knows a good story when he sees it. He opened the book with a cracker, about Léon Scott's mid-nineteenth-century invention, the "phonoautograph." This machine successfully translated the vibrations of the human voice into marks visible on paper — only (almost incredibly) for twenty-first century technicians to reverse the process, treating present-day listeners to an indistinct but recognisable snatch of "Au Clair de la Lune" from an age before audio-transmission was even imagined, let alone possible. Menke's last main chapter also involves a time-slip with a surprising denouement. "A Connecticut Yankee's Media Wars: Orality and Obliteracy" is a virtuoso treatment of Twain's black comedy in which the hero, Hank Morgan, a nineteenth-century American, finds himself transposed to Arthurian England. His attempts to bring it forward into the technological age have an alarming outcome, as he deploys modern machine warfare, in the form of mines and Gatling guns, on an army of knights. Again, Pettitt comes to mind: her fears about the abstraction of the human element certainly seem to be realised here. But, Menke points out (and this is the real twist at the end), Hank's efforts do not really change the course of history: he reawakens in his own age, when the past has already happened, and been recorded in print.

The scholarly apparatus of each of these unusually thought-provoking books is exemplary (and authentic!): Menke's notes and bibliography run to more than fifty pages. Yet, significantly, mentions of the fin de siècle are few and far between: Penny Fielding and Andrew Taylor say in their introduction that the term has been consciously avoided in their collection, and it is not used at all in Menke's text. It only appears in the title of two of the books he cites. The various authors' interests consistently lie in change rather than ending, in progress rather than decadence. They acknowledge their fears for the future. Nevertheless, Menke calls on us in his "After Words" to be more open to it. As far as the printed word is concerned, he cites recent encouraging publishing data, and reminds us of the prediction in the Book of Ecclesiastes, "of making many books there is no end". Lest we should be infected by the wisdom-speaker's world-weariness, Menke then reminds us of Twain and Tesla as they appear in his cover picture, the one being brightly illuminated by the technological advances of the other.

Bibliography

Fielding, Penny, and Andrew Taylor, ed. Nineteenth-Century Literature in Transition: The 1880s. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. Hardcover. 249 + xi pp. £75.00. ISBN 978-1-107-18190-8

Menke, Richard. Literature, Print Culture, and Media Technology, 1880-1900. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019. Hardcover. 259 + ix pp. £75.00. ISBN 978-1-108-49294-2

Created 20 March 2025

Last modified 23 October 2025