iven Jerdan’s fascination with shows of all kinds, and particularly the theatre, it was natural that he should first admire and then befriend the great tragic actor of the day, William Charles Macready. An Irishman without a sense of humour, he was ill-tempered and “had a hearty and ill-concealed contempt for his calling” (Macready Diaries). Macready crossed swords with his rival actor Charles Kemble who, in 1822, took over Covent Garden Theatre and moved in 1823 to Drury Lane. His failings were to give “far too much rein to over-sensitiveness and a disposition to manufacture grievances”. As time went on he did not need to manufacture the grievances he had against Jerdan; he had all too much reason for them. Macready entered into a long-running battle with Alfred Bunn, the stage manager at Drury Lane, which had been taken over in 1831 by a Captain Frederick Polhill. The vendetta against Bunn played out in Macready’s Diaries which commenced in 1833.

The Victoria Theatre (or The Old Vic, originally The Royal Coburg Theatre). Click on images to enlarge them.

In May of that year Macready received a visit from Thomas Gaspey, an acquaintance of Jerdan’s, and occasional contributor to the Literary Gazette. Gaspey warned Macready of “Jerdan’s habit of laying his friends under contribution”; this warning was “kind but needless”, Macready noted, and was to come to wish he had listened more carefully. In August 1833 he dined with Jerdan at the Garrick, and they went together to the Victoria Theatre; he invited Jerdan to visit him at his country home at Elstree the following week.

Jerdan’s friend Edward Bulwer was instrumental in getting a Bill passed in Parliament to establish copyright for drama. In light-hearted mood, Jerdan wrote as ‘Teutha’ from the Garrick Club, making fun of the politician:

The Drama: A Squib

Bulwer, my friend, you’ve framed a bill –

I fear ‘tis all bow-wow –

To regulate the Drama’s course,

For where’s the Drama now?

To Covent Garden should you pass,

The doors are shut, I vow,

And all the actors sent to grass,

So where’s the Drama now?<

/p>

And more, thirteen verses in all (Literary Gazette, May 1833, p. 300).

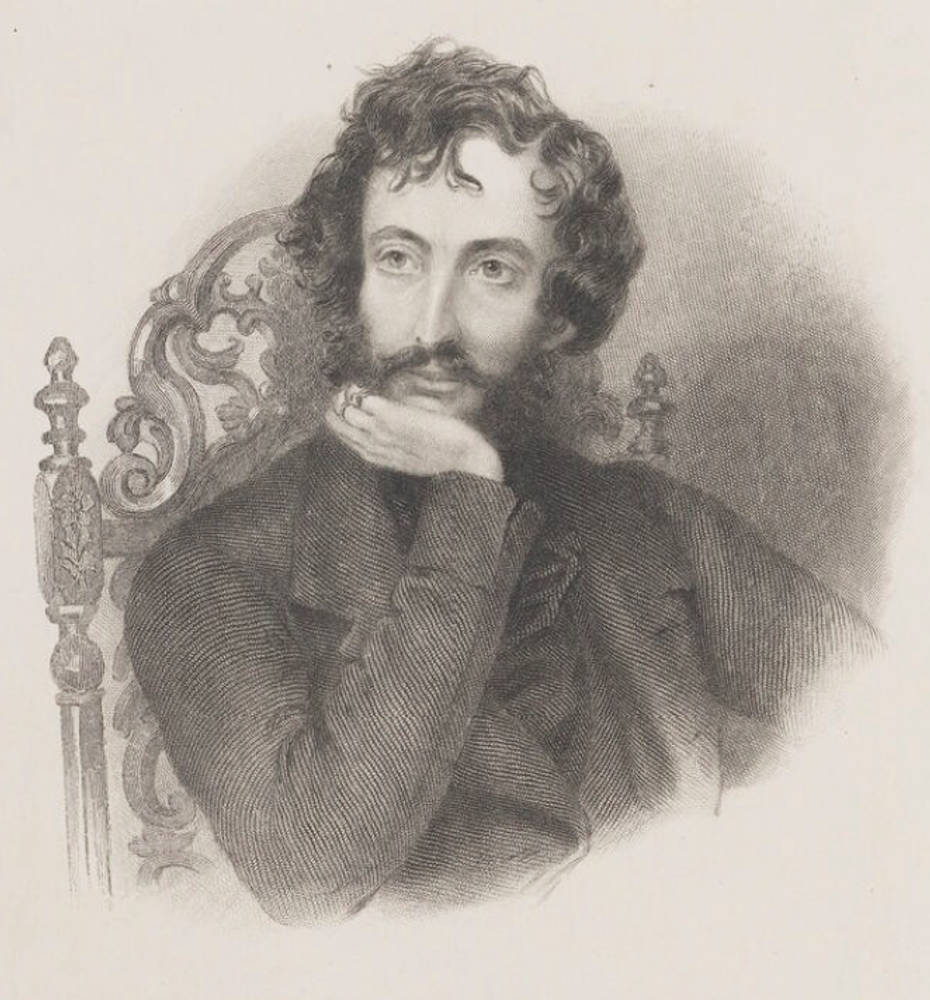

William Maginn by Daniel Maclise from Jerdan’s National Portrait Gallery.

Her real and putative lovers crossed swords in April 1833. As a critic, Jerdan tried always to be kind and positive, especially towards the work of colleagues and associates. It must then have been difficult for him to write to Richard Bentley concerning an anonymous new novel Godolphin which was by Bulwer, although Jerdan may have only suspected this when he wrote his letter:

Finding it impossible to meet your idea of Godolphin, I was most reluctantly compelled to omit the Review of it yesterday. A work of great talent it unquestionably is; but the able author has taken a wrong and perverted twist, which infects his whole story, and spoils what, with a sounder view, would have done credit to any writer now living.

I am very sorry for this on every ground; and especially because I am sure that what springs from private and individual feeling will scarcely meet with general success. It is impossible indeed to make other characters and the action of a fiction conform to such a feeling; and this induces inconsistency throughout. I look upon Godolphin therefore altogether to be the mistake of a person as capable of writing successfully as any of our time.

This was a hard-hitting critique, particularly since Bulwer had six earlier novels published, including several best-sellers, such as Pelham. He was to be hailed the following year by the American Quarterly Review as “without doubt, the most popular writer now living” (quoted DNB)j. The faults Jerdan found in Godolphin were ones Bulwer knew himself. Having been the target of furious attacks by Maginn, Thackeray and others for his previous book Eugene Aram, which made a hero out of a murderer, Godolphin was published anonymously. Jerdan, or possibly Landon, reviewed it in the Literary Gazette of 11 May, in similar vein to his letter to Bentley, devoting in all five and a half columns to comment and extracts. Other periodicals gave it a lukewarm reception, even the New Monthly Magazine of which Bulwer himself was editor. The strain of vituperation and the consequences of his huge output of writings over the past decade told on Bulwer’s health. In the summer he resigned from the editorship of the New Monthly Magazine and travelled with his wife to Italy in an attempt to save their marriage, after his indiscreet liaison with a society beauty. How Jerdan must sometimes have envied Bulwer’s economic independence, to be able to relinquish his duties so easily, relying confidently on the income that his writing brought him, as well as hoping that his mother would eventually accept his marriage, and thus raise expectations of his family connections.

A clue that Jerdan was not as happy as he could be is found in a letter from his old family friends Ellen and John Carne. They wrote on 12 April 1833 thanking Jerdan for his kindness, sending warm wishes to Mrs Jerdan, Agnes and Mary, inviting them again to visit Cornwall. Their letter hoped for Jerdan "much more happiness than you have at present be your portion” (Bodleian Library MSD. Eng. lett. d. 113, f100). The unhappiness to which they referred could have been caused by the ongoing rumours about Landon and her imminent engagement, or more probably, the rough time he was getting from the gutter press. The Carnes’s letter indicates that on family matters nothing was amiss – Frances and the daughters were still at home in Grove House.

Jerdan was embattled on another front besides his association with Bentley. He was still in financial trouble and received a terse letter dated 23 November 1833 from Reese at Longmans who had been approached by Twinings for one hundred and twenty-five pounds Jerdan owed to them (University of Reading, Special Collections, Longman Archives, I, 102 198H). Jerdan had made an agreement to pay the bank but had not complied, and Longmans warned him that they would have to release the funds unless he did so himself. Five days later Longmans told him that as he had not replied, the money had been paid to Twinings. This sum was presumably added to the advances already made to Jerdan. Another probable cause for Jerdan’s unhappiness was the continual struggle to keep control of the Literary Gazette as he fought against interference from his partners and from Richard Bentley, who wanted him to “puff” their productions, and even to dictate the placement of important reviews. In June he had occasion to protest to Bentley:

As you have departed from the old and wonted course which you assured me you would always follow, it is less in my power to do all I could wish in regard to your publications. But you may rely upon it, I shall ever be happy to do my best for you; tho’ I decline running in common and equal harness with inferior periodicals – you must see that it would not do for the Gazette at its price to have too much of the same external features and appearance as the cheaper papers. I perceive today how right I was in not putting Beckford first review; but in all these matters I wish to be clearly understood – I object to nothing done for others to wean them from the system of attack and abuse which a publisher might fear; nor do I court any favour for myself. My course under every circumstance is unbiased and founded on principles not to be shaken; only I must shape it somewhat differently as the case requires. [21 June 1833]

A few months later Jerdan again complained to Bentley, “I must also repeat my other standing objection to be made the organ of common communications – it wd destroy the whole character and power of the Gazette to serve you and any one; by showing that it was the vehicle of the opinions of others and not of its own unbiased judgment” (16 October 1833). Jerdan did not anticipate these private letters becoming public, so he was not grand-standing his repeated claims of independence. When he came to write his Autobiography twenty years later, such claims were for public consumption and for posterity, and were only to be expected. His private correspondence therefore is more convincing, setting out the ethos as to how he believed the Literary Gazette should be conducted.

A new magazine, the National Standard, burst upon the scene in January 1833. Jerdan warned of “ cheap periodicals” in Literary Gazette articles even before it appeared. Its price was two pence. The front page of the first issue of the Standard noted sententiously that it “contained the same quantity of material as the eightpence Literary Gazette and considerably more matter than the fourpence Athenaeum” On an inside page, Thomas Hood made Jerdan and Dilke figures of fun, portraying them as desperately anxious about the new competition:

Jerdan, for instance, has been crying before our office door: aye, actually dropping An Editor’s Tear

Before the door he stood To take his first sad look At the page as large as his Gazette, And the twopence in the nook. He paused till “Oh how cheap,” grew quite Familiar to his ear, Then thought of eight-pence for his own, And wiped away a tear.

Beside that office door Poor Dilke was on his knees, He held an Athenaeum sheet, That fluttered in the breeze. He cried out “That can never last, It’s cheaper than this here,” – But when men shouted “Yes, it will” He wiped away a tear.

They turned to leave the spot, Yes, Jerdan did – and Dilke, Both saying that, “a sow’s ear next Would make a purse of silk.” Go – wait another month or two, You’ll find it pretty clear, That when we talk of our success, They’ll wipe away a tear.

The first editor of the National Standard was F.W.N. Bayley; five months after it began, the paper was bought by Thackeray and lasted only until February 1834 when Thackeray was confronted by financial disasters. Jerdan and Dilke had the last laugh, this time.

William Wilkins’s National Gallery with James Gibbs’s St. Martin-in-the-Fields’s at right.

According to his Autobiography, Jerdan used the Literary Gazette as a platform for various campaigns, one of which was a fight against the building of the National Gallery in Trafalgar Square, “the perpetration of which unseemly job I in vain endeavoured to prevent, brought on a fracas and complaints and hostilities of a rather bitter description” he said (2.193). He ran a determined campaign, setting out several cogent reasons for objecting to the proposed building. He approved, at least, of the site, the Literary Gazette of 23 February 1833 admitting that “the site assigned is most eligible; with every local capability, central, convenient and obvious to view” (122). But, the Literary Gazette of 2 March 1833 argued, such a public building should “stand single and alone in grandeur and grace, rather than see it cabined, cribbed, confined – a masked battery for soldiery, with gateways through which to debouch, should occasion require it” (120). Moreover, the dirty London air would ruin the pictures. A serious objection was the capacity of the proposed building to house the national art collection; no extension was possible with the barracks on one side and a poor house in the rear. This would surely discourage future benefactors from leaving collections to the National Gallery. Wilkins’s building would partially obscure the church of St. Martin’s, cutting in half the view of it from Pall Mall. The Royal Academy which, under the present proposal, would be housed in the middle of the National Gallery, should “be placed where it ought to be, by itself; it gives up, it is said, the worth of £50,000 in Somerset House, and ought in return to have an adequate provision made for it. Do not let us drivel away our means and our character together for a worthless folly, and lose this almost last chance of excellence by niggardly dabbling in fantastic theories” (137). The architecture itself came in for damning criticism; Wilkins’s “pure Greek” style may not be suitable in London.

The difference between a Grecian plain and Charing Cross; between an ever-bright sky and our smoky atmosphere; between insulation and architectural confusion, does not seem to have been considered in a theory which would bend every thing to an idea of abstract grace. Mr Wilkins’s other buildings, Downing College Cambridge, the London University and St. Georges Hospital, are samples – the new work will be the least elevated of them all. [23 February 1833]

Various changes were made to the design, some of which answered Jerdan’s complaints. By the 14 September 1833 number of the Gazette, Jerdan admitted that he was beaten: “Wilkins’s Greek job…IS ACTUALLY IN PROGRESS”. He followed up with a dozen reasons why “We lament” this decision, “but above all, we lament it on account of its being done in the face of the disapprobation of the country, of every man of taste and judgment in art and after the blinding mock discussion in the House of Commons, in order to get the vote of a sum of money upon other provisos and pretences… but complaint seems useless as a reason and we shall only add a pithy quotation: IT IS TOO BAD!" (586).

Better-qualified men than Jerdan also objected to the design of the Gallery; Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin and Charles Robert Cockerell wrote against it “as the epitome of a debased and demoralized architecture” (Conlin 366). The Gallery did expand however, when the barracks and the poor house were demolished, and in 1869 the Royal Academy found another home in Burlington House and in 1895 the National Portrait Gallery moved to its own building. The National Gallery itself, both as an institution and a building, has a long and detailed history, the latest incarnation being Prince Charles’s rejection in 2004, of the proposed extension as “a monstrous carbuncle on the face of a much-loved and elegant friend", in favour of what is now known as the Sainsbury Wing, an addition which would surely have earned Jerdan’s renewed disapproval.

Jerdan never allowed himself to be so distracted that he forgot his charitable interests. The Literary Fund continued its work of donations to needy writers, but still came under occasional attack. One writer, R. H. Horne, asked in 1833 whether it had enabled anyone to write a fine work, and wondered how many ‘men of genius’ had been relieved from distress. It was not the Fund’s purpose to sponsor literary works, “though in fact it did so on several occasions… the Literary Fund had given grants to some twenty men and women of distinction and at least six hundred other authors, and was to recognize Horne’s own literary merit by granting him a total of £430 in his declining years” (Cross 15), Reviewing Horne’s work Exposition of False Medium and Barriers Excluding Men of Genius in which his accusation was made, Jerdan had taken the trouble to consult the Fund’s records and could refute Horne’s allegation in the case of a Mr Heron in 1807. The Fund was flourishing, and had increased its bounties. As the Literary Gazette of 14 September 1833 pointed out, “were it possible for its presence to be generally known, there would be found very many cases of such exquisite misery turned into joy and gladness as would shame all the invented pathos of romance, and we are convinced, excite thousands to contribute to the increase of so patriotic, so interesting and so nobly benevolent a resource, where the destitute and deserving never seek help in vain and where judgment and pity ever go hand in hand in lifting up the oppressed and saving the broken-hearted” (580). Jerdan’s evident passion for the Literary Fund clearly over-rode his objectivity in assessing the worth of Horne’s work, although in line with his usual practice of being “fair” gave the book (which was dedicated to Bulwer), three instalments in the Literary Gazette.

Jerdan was always alert for those in real need, and claimed to send to the Literary Fund any monies received by the Literary Gazette incorrectly. “From this source frequent and considerable subscriptions were derived” (4.34). He cited £50 from the Marquis of Normanby and £67 from the well-known novelist G.P.R. James as Jerdan’s fee for negotiating the sale of some manuscripts for publication A letter from W. Jerdan to Colburn and Bentley requests them to send him £75 for Mr James’s MSS payable to the Literary Fund probably for James’s “String of Pearls”; this may have been a different occasion which would account for the discrepancy in the sum named (Ransom Humanities Research Center). He related an anecdote in which he met an old man, feeble and poorly clothed, walking near Grove House. Touched, Jerdan spoke to him and proferred half a crown, which was declined. The shabby old man turned out to be wealthy, and thenceforward donated £20 annually to the Literary Fund because of Jerdan’s kindness and his connection to the Fund.

Even whilst revelling in the good living and parties at Grove House, Jerdan was still painfully aware of others’ poverty. He heard of a sad case just nearby and, on visiting the writer who had produced some creditable work, found him sitting stupefied, a dead three-year old in a corner, and the mother with another child on a makeshift bed on the floor. Jerdan immediately arranged for the child’s burial, for the family to get food, and for the rent arrears to be paid. In such a case he conceded that those who criticised the Literary Fund for giving too little too late were right. He gave this man some assistance for years, horribly aware that he could not fill the needs of all penniless writers. Such straits were painful to behold, and strengthened the view that became a theme of his memoirs, that writing was a chancy business and could not be relied upon for a living.

In January 1834 Jerdan began a series of eleven articles on “The Publishing Trade”. His main target was the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge and its “Superintending Committee” whose Chairman was the Lord Chancellor; the list of its members featured many in exalted public office. Jerdan’s first front page article drew on support from Colburn’s other journal, the New Monthly Magazine which had dealt with the same matter in its January issue. Jerdan attacked the current “low estate” of literature and the cheap publication of compilations and “monthly epitomes of every sort” in which “the beauty of the arts, and the utility, not to say the dignity of letters, are utterly sacrificed.” What really upset him though, was the “false pretence” of the Society. The Committee of “high names” raised subscriptions for the Society’s range of publications “(Almanacs, Magazines, Cookery, History, Penny Cyclopaedias etc.)” under the guise of diffusing useful knowledge among the poorer classes of the people. Jerdan insisted that this was “a shameful violation of just principles, a gross invasion of private property, and an odious monopoly most injurious to the true interests of learning and the freedom of the press”. He challenged the notion that the men on the Committee actually “superintended” any of the publications, asking rhetorically if the Lord Chancellor’s official duties could be neglected so as to oversee fourpenny maps and tenpenny portraits. He believed “the whole matter is fallacy and fudge; that they have not even seen the works sanctioned by their names.” Moreover, in addition to this deception, Jerdan stated that such public officials “have no right to impose upon the people by lending their names to subterfuge and falsehood…Is it proper that the highest dignitaries of the law and state should be at the head of a publishing club?”

Jerdan’s article then turned to the old question of puffing, listing examples which were designed, he said, to mislead the public and ultimately to disappoint purchasers of the books so puffed. He deplored “the new method of manufacturing books merely for the ready market of the day”, the pursuit of profit with no regard for the quality of information or content. Promotion of the worthless, he maintained, shut out the worthy. “They load the public with the poor and injurious production of the venal and profligate, while they exclude from the press such works as would improve the age, and reflect an honour upon our national literature.” In a direct attack on Colburn, with his staff of paid “puff” writers, Jerdan made a pointed reference to “the clever project of having a band of hacks in regular pay, organised to tell readers what they ought to think of other hacks also in regular pay – the aforesaid hacks, as need arose, changing places at a wave of the conjuror’s golden wand.”

The remaining articles in the series of “The Publishing Trade” expounded at greater length on the matters set out in the first. Jerdan looked back and claimed some credit for the Literary Gazette “for having, in a considerable degree, checked the career of what were miscalled fashionable novels, of which not one in forty ought ever to have affronted the public taste and judgment”. Jerdan was not against dissemination of knowledge, whether useful or merely entertaining, but in these articles he insisted that books should be of a high standard, otherwise they were

proportionately injurious to the growth of human intellect…when we begin with inaccuracy and trumpery, the desire created is for the same sort of ignorance and trifling; the readers have made to real acquisition to their means of comfort or enjoyment, and having only learnt what is wrong, the end, instead of improvement, is dissatisfaction; instead of content, presumption; instead of moral and religious truth, restlessness of disposition, and vicious indulgence.

Jerdan’s agenda was to raise awareness of the low standard of the books put out by unscrupulous publishers, in which he included the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, as being interested solely in profit, but under the cloak of educating the poor. Henry Vizetelly agreed with him saying that the Society was “bent upon teaching the working classes something of everything, if not everything of something” (1.85). Jerdan accused the Society of being a monopoly with unwarranted power to injure fair booksellers and publishers, “(individual competition forming the mass of national wealth and prosperity)”; he reproduced a letter which had appeared in The Times, asking Lord Brougham the Lord Chancellor and Chairman of the Society, to consider his position should the Society face an injunction for literary piracy – as many of their compilations merely copied from other works without acknowledgement. The Chairman would have to defend the Society before the Lord Chancellor – that is, himself. Jerdan called upon these “eminent men” to resign from their bookselling concern and “leave the publishing trade as they found it, open”. The following week he listed those who had left the Committee since its inception and those who remained.

He then turned his fire on to another Society which, thinking the Useful Knowledge diffused by the first one was not sufficiently religious, formed The Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, supported by voluntary contributions. Jerdan called this “unwarrantable competition”, the contributions paying for printing and publishing religious tracts and bibles, risking the funds subscribed, and by implication, taking work from genuine publishers and booksellers. In an effort to be fair, Jerdan printed a letter supporting cheap reprints of original old books, which would otherwise be beyond the reach of most people’s pockets. He had no objection to this type of cheap publication but every objection to piracy and plagiarism. He devoted his fifth article to this, naming works so pirated. So that there should be no misunderstanding his reasoning, he clarified “It is the principle which we denounce and reprobate. We care not one farthing for any publisher existing; but it is unjust to every private interest, unfavourable to the pursuits of literature, and injurious to the country, that these scandalous monopolies should be established and supported under false pretence.”

In the seventh of his series, Jerdan reproduced extracts from “The Printing Machine: a Review for the Many”, an attempted rebuttal by the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge against his earlier articles. He selected their attack on the Literary Gazette’s own position as a “cheap paper”, to which Jerdan parried that “Dearness and cheapness are not merely comparative but convertible terms. One sheet may be dear at a penny – another cheap at half a crown. It is the merits, not the bulk of periodicals, that we contend for…” He held their detailed accusations to ridicule, letting them be hung by their own words, generously conceding, “To be sure it is but bread and water after all; but then consider the quantity – as much as you can drink and all for the small sum of One Penny.”

The fight became personal, Jerdan accusing the writers for the Society of being careless of “one grand element of knowledge – namely, Truth”. He spoke highly of Charles Knight, publisher of “The Printing Machine” and of most of the Society’s works, absolving him from the errors and untruths of the other writers. If they had only asked Knight’s opinion, Jerdan said, they would have avoided “some of their negligent or wilful misrepresentations”. The Literary Gazette had been accused of encouraging young, and sometimes indifferent writers, a charge to which Jerdan pleaded guilty; his “leaning was decidedly to cherish the youthful to higher efforts…Our chiefest boast is having done precisely what is here alleged as a fault.” He confronted other criticisms in the same tone of patient explanation, ending by repeating his core philosophy, from which he did not waver his whole life: “…truth and kindness and mercy are the best canons of criticism.”

Jerdan was sensitive to the allegation in “The Printing Machine” that because of the vast numbers of new books pouring off the presses, it was impossible for a weekly periodical to offer a valuable criticism, joking that it was like sticking a bodkin into a ham and smelling it to see if the meat was cooked – a joke reflecting the one from his detractors, that Jerdan cut the pages of a new book with a paper knife and smelled it for the book’s contents. He vigorously refuted such allegations, turning the attack towards the “essay writing” of the monthly and quarterly reviews, and insisting that if there were “more of mere judicious reporting, in every periodical devoted to these pursuits, we should deem it a very essential gain and benefit to the public.” He had read three hundred pages of a review, he complained, without learning anything about the book it purported to discuss.

Stung by the suggestion that his attacks on the cheap mass productions of the publishing societies were in effect support of a “tax on knowledge” Jerdan was crystal clear: “The Literary Gazette is, and has ever been, as warm and sincere an advocate as the Penny Magazine for the unlimited instruction of every class of the people. We hold education to be the staff of life to the mind, as much as bread itself is the staff of life to the body; and we should as soon think of desiring the former to be stinted as the latter. God forbid that we should do either!” It was the quality of mass publishing he decried, and even more, the self-congratulation of those eminent men who promulgated it. It was not because of the cheapness of the publications “that we dislike them; but because they are BAD.”

His final article in this series on “The Publishing Trade” was in April, and noted that the articles had made people realise the dangers of the “inferiority…like an insidious weed [which has] been creeping over the fair and fruitful class of literature.” Dismissing the old chestnut that the Literary Gazette always gave Colburn’s books undeserving praise, Jerdan said that he was not going to defend all Colburn’s novels, but that along with “the many bad ones, he also published many of the best in our day”, and reminded readers that the Literary Gazette’s reviews of the bad ones had driven Colburn to take a share in the Athenaeum.

The whole series of Jerdan’s articles can be taken as his creed for the publishing industry at the time, for his personal philosophy, and even for his political views. Some points were personal, like his grievance against the “worthies” of a subscription body who did not, as they claimed, superintend the works put out in their name. Other arguments he made were clearly deeply felt and genuine, but with hindsight read like the protests of a man embattled against the oncoming tide.

Landon wrote Jerdan on 10 June 1834 asking him to approach Bentley “in the most forcible light” for an advance; she planned to set her next novel “in Paris during the latter end of the Revolution” and needed local colour (Sypher Letters 101). She wanted new ideas and to escape for a while from money worries. Only a very few letters between Landon and Jerdan seem to have survived, and most of those that have are printed by Jerdan in his Autobiography. They are from Landon on her trip to Paris in the summer of 1834 and from their often affectionate and playful tone indicate the close relationship between the two correspondents who, if they were no longer in the throes of a sexual relationship, were still good friends and colleagues.

But there may well have been more than friendship at this time, despite the interruption of Landon’s engagement to Forster. In Unpublished Letters of Lady Bulwer Lytton to A E Chalon in 1914, was a letter concerning an incident in the mid-1830s, told from a perspective of twenty years after the event.

Left: Edward George Earle Lytton Bulwer-Lytton, 1st Baron Lytton. G. Cook after Richard James Lane. 1848. Right: Rosina Anne Doyle Bulwer Lytton (née Wheeler), Lady Lytton (1802-1882). Engraving by John Jewell Penstone after Alfred Edward Chalon. 1852. Both courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery, London.

According to Rosina’s husband, ‘that loathsome satyr, old Jerdan, in one of his drunken fits at some dinner let out all his liaison with Miss Landon and gave her name coupled with some disgusting toast.’ Rosina Bulwer Lytton says that she then warned Landon not to admit Jerdan, and Landon promised not to, but not long afterwards, making a surprise visit to the poet’s room at the boarding house, she found ‘Miss Landon on old Jerdan’s knee, with her arm around his neck!’ This moved her to end her long friendship with Landon. No one has ever paid much attention to the allegations made in her letter to Chalon. [Lawford]

However, it has been noted that by the time this letter was written, Rosina “was so far gone in hysterical loathing of Bulwer and everything connected with him, that to throw filth at his friends had become a form of indulgence of her hatred of himself” (Sadleir 423). Rosina’s hatred for Jerdan was an old story, probably simply for the reason that he was a friend of her husband’s, but if there is any truth in her account of surprising Jerdan dangling Landon on his knee around the mid-1830s, it seems quite likely that the affair was not yet over.

Jerdan was, as always, trying to help Landon’s family. In a letter of 14 July 1834 her brother urgently asked Jerdan to meet a bill of fifteen pounds. Whittington had not had a successful career, but his letter claimed that he was attempting to improve. “I have done all I could for the last three years to recover the effects of former errors and faults by my conduct.” He had been advised to publish a few sermons, “it must do me good – it will shew the authorities, tho’ unhired, I have not been idle, positive failure cannot lower me in opinion because opinion never raised me” (Bodleian Library 114-11). His sister had paid his way through Oxford and was probably still supporting their mother, so Whittington may not have felt able to face asking her to meet his debt. It is somewhat ironic that he turned to Jerdan for help, a man equally bad at managing his own finances. Jerdan did what he could to help, reviewing Landon’s Ten Sermons Preached in the Parish Church of Tavistock in the Literary Gazette in December 1834, linking him with his “association with the poetry and imaginative literature of our age and country as Mr Landon is through the same of his gifted sister L.E.L” (849). A brief but favourable review followed. This did not please L.E.L. who, three days later on 23 December 1834, berated Jerdan: “I cannot get over my dissappointment (sic) about Whittington’s book. You should have made one or two quotations…can you not say you omitted last week by mistake? And give a column or two?” (Sypher Letters).

Landon continued to review for the Literary Gazette, earning the vilification of Henry Fothergill Chorley, who had recently joined the editorial staff of the Athenaeum as music critic and literary reviewer. “It would not be easy to sum up the iniquities of criticism (the word is not too strong) perpetrated at the instance of publishers,” fulminated Chorley, “by a young woman writer who was in the grasp of Mr Jerdan, and who gilt or blackened all writers of the time as he ordained…It is hard to conceive anyone who by flimsiness and flippancy was made more distasteful to those who did not know her than was Miss Landon” (Chorley 81). Clearly, Landon had written something critical of Chorley’s work, and he was intent on getting his revenge.

As previously noted, public taste in reading was changing rapidly. Musing on the 1830s from the perspective of fifty years later, Walter Besant noted in Fifty Years Ago a turning away from the glut of popular, and often poor, novels of the 1820s, when everyone wanted to be a second Walter Scott. Where publishers had printed two thousand copies, they sold only fifty, and at the same time “The drop in poetry was even more terrible than that of novels. Suddenly, and without any warning, the people of Great Britain left off reading poetry.” Dickens, Thackeray and Eliot redeemed the novel by their huge success, but otherwise the public turned to books of non-fiction: travel, exploration and science. Besant noted that for instance, James Holman’s ‘Round the World’ (1834) and Lamartine’s ‘Pilgrimage’, sold at least a thousand copies each. Landon had been just in time in producing her novels, although she was still churning out poetry for the annuals. Besant’s opinion was that “one of the causes of the decay of trade as regards poetry and fiction may have been the badness of the annuals.” Beautifully printed and bound, the engravings were interesting, but the literary content was of much lower quality.

The Literary Gazette however, remained consistent to its pattern of the last twenty years, Jerdan failing to notice, or to acknowledge, the changing tastes of his readers. This was by no means his only problem at this time. According to one opinion, another factor was that the Literary Gazette “continued to review the fashionable novels seriously, while almost all the other reviews…were decrying them without mercy…the Literary Gazette was still addressing those who were ambitious to move above the salt, or at least dream about it” (Duncan 160). Duncan here disagrees with Jerdan himself who pointed out in “The Publishing Trade” articles that he had omitted reviewing “fashionable novels” to a great extent. Fraser’s was still on the attack: “To say that the Literary Gazette is feeble, is certainly not being very original; it should be called the Laudatory rather than the Literary Gazette. With it ‘all is fish that comes to net’” (Jan-June 1834): 724).

No stranger to finding himself in a Court of Law, Jerdan was again dragged into a case heard in the Lord Mayor’s Court in July 1834. According to The Times of 14 July 1834. He was not a principal in the action, which was Chambers v. Longman & Co., but it was a case of “attachment”. Chambers was a tailor who claimed that Jerdan owed him £315, a huge sum. He knew that Longmans held money of Jerdan’s, paid him a salary as editor of the Literary Gazette, and also a share of the profits. Longmans denied they held any money belonging to Jerdan. The publisher Scripps was questioned and explained that proceeds from the sale of the Literary Gazette and its advertisements were paid directly to Longmans. A clerk from Longmans was then called to confirm that he handed Literary Gazette money to Longmans every week, and knew nothing of any money belonging to Mr Jerdan. The unfortunate tailor lost his case, having failed to make a claim which convinced the Recorder.

In 1834 the seeds of yet another financial disaster were sown for Jerdan. This time it was of his own making, not due to collapsing banks as had previously been the case. This was a disaster of immense consequences for him, and he felt the pain long afterwards, devoting only a few pages to the incident in his Autobiography, but no other mention or reference to it is made in surviving letters. There is thus only Jerdan’s own account and this is guarded as even twenty years later he divulged no names or corroborative details.

Jerdan related how a wealthy man had returned from India with two sons; they lived in a handsome square in high style. The sons were gifted and had literary ambitions, swiftly establishing a place in society. They became intimate friends of Jerdan’s and he watched them for years as they rose in literary repute and reward. “The foundations were hollow”, he wrote, and despite their gains in reputation, “the whole superstructure fell miserably to the ground, and the sunny times were lost in painful darkness” (4.358). Jerdan had participated in some of their endeavours, more as a friend than on a formal basis, as he admired their cleverness and abilities. Jerdan was induced, “for certain reasons” which he did not disclose, to negotiate a contract with one of the brothers, for him to take over a portion of Jerdan’s work in the Literary Gazette. The partners were brought into the negotiations. Whilst talks were proceeding, the other brother “entered into a copartnery with one of a reputedly very rich Jewish family in the city”. Dazzled by this alliance, Jerdan “in an evil hour” put his name to several large bills, “to enable him to show something against the Leviathan fortune in the administration of which he was about to participate as a broker.” It does not seem to have occurred to Jerdan that the father of the two brothers, reputedly so wealthy, would have been the man to guarantee his son’s investment, but he clearly believed he was running no risk in doing so himself.

Things fell apart; the negotiation concerning the Literary Gazette failed, as did the promising brokerage. Jerdan was sued for between three and four thousand pounds. He was ruined. Looking back to this time, he sought to find a moral in the story. The brother with whom he was closest was a happy, spirited individual, welcomed everywhere. He had not a vicious or evil disposition. “What then,” asked Jerdan, “caused his downfall? Vanity! Vanity alone led to boasts and falsehoods”, to an extent that the young man could no longer distinguish truth from lie. Jerdan approached the bankers who held his bills, apprising them of the “real state of the case”, and that he had personally received absolutely nothing in exchange for his guarantees. The bankers offered to forgo their claims on him – all he had to do was to get a letter stating this fact from the brother for whom he had signed the bills. Relieved and elated to be so close to salvation, Jerdan requested such a note from his friend. The man had, however, told so many lies on such a scale when depositing the bills at the bank, he could not bring himself to do as Jerdan asked, which would have shown himself to be a liar. Accordingly, he fled to the Continent, leaving Jerdan “to bide the brunt of my unpardonable imprudence”.

In his account, it must be to Jerdan’s credit that he did not try to whitewash his own vanity or greed, but noted it for what it was, the character flaw that had dogged him always, imprudence and a misplaced faith that as in his childhood ‘spoiling’, things would work out well despite his behaviour. The consequences of this incident were catastrophic. Jerdan was forced to sell his beloved Grove House, scene of so many happy parties and home to his large family. The contents went to auction, fetching less than he had paid Wilberforce for the fixtures alone, and adding a further thousand pounds to his losses. He was obliged to take up residence in the Westminster Bridge Road. His long-suffering wife would have had to bear the strain not only of moving from a grand house to lodgings, but of having to cope with a husband whose bad judgment alone had brought such disaster down upon them.

Focused by the recent introduction of workhouses in the Poor Law Amendment Act, Jerdan said that “by every possible sacrifice” he met all his debts, but in doing so he incurred other “incumbrances”. The Literary Gazette was falling in circulation, as a direct result of the Athenaeum halving its price. This in turn led to Longmans losing interest in the Gazette. The publisher too was older and overworked, causing errors to creep in. Jerdan was frustrated to hear that “while I was losing more and more from week to week, one of my employés, at a guinea-a-week wages contrived, as I am informed, to save enough to purchase houses!!” (4.361). All this misfortune was the beginning of the long and slippery slope that was the remainder of his life.

In an undated letter to Bentley, Jerdan told him, “I have exposed myself to be swindled out of a ruinous sum, which however I am assured can be avoided by an immediate payment of no very large amount, but at present out of my power. What to do for about £100 I know not, and if I do not find them, I dread the consequences of a law suit with a scoundrel attorney at the head of a conspiracy to defraud me.” Undated as this letter is, its contents could have applied to several occasions in Jerdan’s life from this time onwards. He also told Bentley that he was involved in a “soap concern” which could be used as collateral. Benjamin Hawes’s successful soapworks was a prominent landmark at the Temple, near to Jerdan’s office, and perhaps this gave him the idea to go into the business. No more was said about the enterprise.

On 23 April 1834 Macready gathered some friends for a private supper at the Garrick, including Forster and Talfourd. The number of guests increased, some were even strangers to him. Then he noted, “Jerdan was amongst us! And I thought (not, I hope, uncharitably) that it would have been more graceful to have absented himself from a festive meeting under his peculiar circumstances which he evidently cannot feel very strongly” (Macready Diary). Most probably Macready referred to Jerdan’s downfall although he did not know any details, merely surmising that they were “probably of a financial nature”.

The Literary Fund had sent Macready an invitation which he did not quite understand, and he called at the Literary Fund’s office for clarification. The Secretary, Snow, told him that a compliment was intended, but they would not even drink his health if he preferred. On that basis Macready accepted their invitation and spent the following week in a state of nerves, writing his speech. On the day of the Dinner, Jerdan presented him to the Duke of Somerset, President of the Fund, and he enjoyed the company and the dinner, overshadowed only by worries over his speech which, in the end, he was not called upon to make. On 18 August Jerdan and Landon shared a box at the Opera House for one of Macready’s performances, and were joined afterwards by the actor and John Forster.

Fraser’s Magazine still ran its series, ‘Gallery of Illustrious Literary Characters’, of which Jerdan had been the first. It now featured the hitherto derided author and publisher Leigh Hunt, on the occasion of his 50th birthday. “He has been an excessively ill-used man in many respects, and by none more than by Lord Byron, and those who panegyrise his lordship”, said Fraser’s (quoted Holden 240). Even Blackwood’s Maga, penitent over ‘Z’s scathing attacks on the ‘Cockney School’ years earlier, praised Hunt’s new periodical the London Journal Here one should note that Jerdan’s old friend and rival William Blackwood died in 1834 and was succeeded by his son. This, as so many of Hunt’s publishing ventures, lasted for only a year, despite, or maybe because, “it was still well ahead of its time in its appreciation of Keats’s significance [in the ‘Eve of St Agnes]” (Holden 241).

In the first issue of his new London Journal, Hunt wrote an obituary for his schoolfriend Charles Lamb, who died in December 1834. Bryan Proctor, whose poetry had first been published in the Literary Gazette and subsequently in Hunt’s own journals, complained that Hunt’s treatment of his friend was scanty and cold. A public row ensued, which was overwhelmed by the country’s concern about an increasingly belligerent Russia, with the British Mediterranean Squadron on standby-by to defend Constantinople in the event of a Russian attack. The peace was a fragile one (Holden 245).

The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834 by J. M. W. Turner. 1835. Oil on canvas, F36 ¼ × 48 ½ inches (92.1 × 123.2 cm) Framed: 46 × 58 &frac716; × 5 ½ inches (116.8 × 148.4 × 14 cm) Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. M1928-1-41. The John Howard McFadden Collection, 1928.

A few weeks earlier, in October, a terrible fire had engulfed the Houses of Parliament, scene of Jerdan’s early journalistic endeavours. It was caused by the burning of a large amount of wooden Exchequer tallies in the stoves of the House of Lords. Jerdan was seen in the crowd valiantly trying to dowse the flames. Only Westminster Hall remained, but on the positive side, the conflagration inspired J. M. W. Turner to paint two famous pictures of the event.

Left: The Burning of the Houses of Lords and Commons, 16 October 1834 by J. M. W. Turner. 1835. Oil on canvas, Framed: 123.5 x 153.5 x 12 cm (48 5/8 x 60 7/16 x 4 3/4 in.); Unframed: 92 x 123.2 cm (36 1/4 x 48 1/2 in.) Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Art. Bequest of John L. Severance 1942.647. Right: The Burning of the Houses of Parliament, by J. M. W. Turner. 1834-35. Watercolour and gouache on paper, 302 × 444 mm. Tate Britain D36235 Turner Bequest CCCLXIV 373.

During the year, within sight of several of the Literary Gazette’s former offices, on the corner of Wellington Street and the Strand, the Lyceum Theatre was built. A special room was included in the building for meetings of the elite Beefsteak Club, about which Jerdan was to write in the last article of his life.

Bibliography

Besant, W. Fifty Years Ago. London: Chatto & Windus, 1888.

Blanchard, Laman. The Life and Literary Remains of L.E.L. London: Henry Colburn, 1841.

Canning, George. Some Correspondence of George Canning. Ed. E. Stapleton. London: Longman & Co., 1887.

Collins, A. S. The Profession of Letters – a Study of the Relations of Author to Patron, Publisher and the Public 1780-1832. London: George Routledge & Sons, 1928.

Conlin, Jonathan. The Nation’s Mantelpiece: A History of the National Gallery. London: Pallas Athene Ltd., 2006.

Cross, Nigel. The Royal Literary Fund 1790-1918. London: World Microfilms, 1984.

Cruse, Amy. The Englishman and his Books in the Early Nineteenth Century. London: George Harrap & Co., 1930.

Disraeli, R. Ed. Lord Beaconsfield’s Letters 1830-1852. London: John Murray, 1887.

Duncan, Robert. “William Jerdan and the Literary Gazette.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Cincinnati, 1955.

Fisher, J. L. Victorian Periodicals Review 39, No. 2 (2006): 97-135.

Gettmann, Royal A. A Victorian publisher, A Study of the Bentley Papers. Cambridge: University Press, 1960.

Griffin, D. Life of Gerald Griffin. London: 1843.

Hall, S. C.Retrospect of a Long Life. 2 vols. London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1883.

Hall, S. C. The Book of Memories of Great Men and Women of the Age, from personal acquaintance. 2nd ed. London: Virtue & Co. 1877.

Holden, Anthony. The Wit in the Dungeon: A Life of Leigh Hunt. Little, Brown, 2005.

Jerdan, William. Autobiography. 4 vols. London: Arthur Hall, Virtue & Co., 1852-53.

Jerdan, William. Men I Have Known. London: Routledge & Co., 1866.

Kitton, F.G. Dickensiana. London: G. Redway, 1886.

The Letters of Letitia Elizabeth Landon. Ed. F. J. Sypher, Delmar, New York: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2001.

Landon, L. E. Romance and Reality. London: Richard Bentley, 1848.

Landon, L. E. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Ed. Jerome J. McGann and D. Reiss. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Lawford, Cynthia. “Diary.” London Review of Books. 22 (21 September 2000).

Lawford, Cynthia. “Turbans, Tea and Talk of Books: The Literary Parties of Elizabeth Spence and Elizabeth Benger.” CW3 Journal. Corvey Women Writers Issue No. 1, 2004.

Lawford, Cynthia. “The early life and London worlds of Letitia Elizabeth Landon., a poet performing in an age of sentiment and display.” Ph.D. dissertation, New York: City University, 2001.

Macready, William Charles. The Diaries of 1833-1851 Ed. W. Toynbee. 2 vols. London: Chapman & Hall, 1912.

Marchand, L. The Athenaeum – A Mirror of Victorian Culture. University of North Carolina Press, 1941.

Mackenzie, R. S. Miscellaneous Writings of the late Dr. Maginn. Reprinted Redfield N. Y. 1855-57.

McGann, J. and D. Reiss. Letitia Elizabeth Landon: Selected Writings. Broadview Literary Texts, 1997.

Pyle, Gerald. “The Literary Gazette under William Jerdan.” Ph. D. dissertation, Duke University, 1976.

Roe, Nicholas. The First Life of Leigh Hunt: Fiery Heart. London: Pimlico, 2005.

Sadleir, Michael. Blessington D’Orsay: a Masquerade. London: Constable, 1933.

Sadleir, Michael. Bulwer and his Wife: A Panorama 1803-1836. London: Constable & Co. 1931.

St. Clair, W. The Reading Nation in the Romantic Period.

Stoddard, R. H., ed. Personal Reminiscences by Chorley, Planché and Young. New York: Scribner, 1874. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing.

Sypher, F. J. Letitia Elizabeth Landon, A Biography. Ann Arbor, Michigan: Scholars’ Facsimiles & Reprints, 2004, 2nd ed. 2009.

Thomson, Katharine. Recollections of Literary Characters and Celebrated Places. 2 vols. New York: Scribner, 1874. Reprinted Kessinger Publishing.

Thrall, Miriam. Rebellious Fraser’s: Nol Yorke’s Magazine in the days of Maginn, Carlyle and Thackeray. New York: Columbia University Press, 1934.

Timbs, J. Club Life of London. London: Richard Bentley, 1866.

Vizetelly, Henry. Glances back through seventy years. Kegan Paul, 1893.

Watts, A. A. Alaric Watts. London: Richard Bentley, 1884.

Last modified 30 June 2020