ord Roberts had now been six weeks in the capital, and British troops had overrun the greater part of the south and west of the Transvaal, but in spite of this there was continued Boer resistance, which flared suddenly up in places which had been nominally pacified and disarmed. It was found, as has often been shown in history, that it is easier to defeat a republican army than to conquer it. From Klerksdorp, from Ventersdorp, from Rustenburg, came news of risings against the newly imposed British authority. The concealed Mauser and the bandolier were dug up once more from the trampled corner of the cattle kraal, and the farmer was a warrior once again. Vague news of the exploits of De Wet stimulated the fighting burghers and shamed those who had submitted. A letter was intercepted from the guerilla chief to Cronje’s son, who had surrendered near Rustenburg. De Wet stated that he had gained two great victories and had fifteen hundred captured rifles with which to replace those which the burghers had given up. Not only were the outlying districts in a state of revolt, but even round Pretoria the Boers were inclined to take the offensive, while both that town and Johannesburg were filled with malcontents who were ready to fly to their arms once more.

Already at the end of June there were signs that the [475/476] Boers realised how helpless Lord Roberts was until his remounts should arrive. The mosquitoes buzzed round the crippled lion. On June 29th there was an attack upon Springs near Johannesburg, which was easily beaten off by the Canadians. Early in July some of the cavalry and mounted infantry patrols were snapped up in the neighbourhood of the capital. Lord Roberts gave orders accordingly that Hutton and Mahon should sweep the Boers back upon his right, and push them as far as Bronkhorst Spruit. This was done on July 6th and 7th, the British advance meeting with considerable resistance from artillery as well as rifles. By this movement the pressure upon the right was relieved, which might have created a dangerous unrest in Johannesburg, and it was done at the moderate cost of thirty-four killed and wounded, half of whom belonged to the Imperial Light Horse. This famous corps, which had come across with Mahon from the relief of Mafeking, had, a few days before, ridden with mixed feelings through the streets of Johannesburg and past, in many instances, the deserted houses which had once been their homes. On July 9th the Boers again attacked, but were again pushed back to the eastward.

It is probable that all these demonstrations of the enemy upon the right of Lord Roberts’s extended position were really feints in order to cover the far-reaching plans which Botha had in his mind. The disposition of the Boer forces at this time appears to have been as follows: Botha with his army occupied a position along the Delagoa railway line, further east than Diamond Hill, whence he detached the bodies which attacked Hutton upon the extreme right of the British position to the south-east of Pretoria. To the north of Pretoria a second force was acting under Grobler, while a third [476/477] under Delarey had been dispatched secretly across to the left wing of the British, north-west of Pretoria. While Botha engaged the attention of Lord Roberts by energetic demonstrations on his right, Grobler and Delarey were to make a sudden attack upon his centre and his left, each point being twelve or fifteen miles from the other. It was well devised and very well carried out; but the inherent defect of it was that, when subdivided in this way, the Boer force was no longer strong enough to gain more than a mere success of outposts.

Delarey’s attack was delivered at break of day on July 11th at Nitral’s Nek, a post some eighteen miles west of the capital. This position could not be said to be part of Lord Roberts’s line, but rather to be a link to connect his army with Rustenburg. It was weakly held by three companies of the Lincolns with two others in support, one squadron of the Scots Greys, and two guns of Battery R.H.A. The attack came with the first grey light of dawn, and for many hours the small garrison bore up against a deadly fire, waiting for the help which never came. All day they held their assailants at bay, and it was not until evening that their ammunition ran short and they were forced to surrender. Nothing could have been better than the behaviour of the men, both infantry, cavalry, and gunners, but their position was a hopeless one. The casualties amounted to eighty killed and wounded. Nearly two hundred were made prisoners and the two guns were taken. With the ten guns of Colenso, two of Stormberg, and seven of Sanna’s Post, this made twenty-one British guns which the Boers had the honour of taking. On the other hand, the British had captured up to the end of July two at Elandslaagte, one at Kimberley, one at Mafeking, six at Paardeberg, one at Bethlehem, three at Fouriesberg, two [475/476] at Johannesburg, and two in the west, while early in August Methuen took one from De Wet and Hamilton took two at Olifant’s Nek — which made the honours easy.

On the same day that Delarey made his coup at Nitral’s Nek, Grobler had shown his presence on the north side of the town by treating very roughly a couple of squadrons of the 7th Dragoons which had attacked him. By the help of a section of the ubiquitous Battery and of the 14th Hussars, Colonel Lowe was able to disengage his cavalry from the trap into which they had fallen, but it was at the cost of between thirty and forty officers and men, killed, wounded, or taken. The old ‘Black Horse’ sustained their historical reputation, and fought their way bravely out of an almost desperate situation, where they were exposed to the fire of a thousand riflemen and four guns. These two affairs were, however, among the last successes which the Boers could claim in a war which had opened with so brilliant a series of victories. Against the long odds of distance, of pestilence, and of inferior mobility, the persistence of the British was slowly wearing down all resistance.

On this same day of skirmishes, July 11th, the Gordons had seen some hot work twenty miles or so to the south of Nitral’s Nek. Orders had been given to the 19th Brigade (Smith-Dorrien’s) to proceed to Krugersdorp, and thence to make their way north. The Scottish Yeomanry and a section of the 78th R .F.A. accompanied them. The idea seems to have been that they would be able to drive north any Boers in that district, who would then find the garrison of Nitral’s Nek at their rear. The advance was checked, however, at a place called Dolverkrantz, which was strongly held by Boer riflemen. The two guns were insufficiently [478/479] protected, and the enemy got within short range of them, killing or wounding many of the gunners. The Lieutenant in charge, Mr. A. J. Turner, the famous Essex cricketer, worked the gun with his own hands until he also fell wounded in three places. The situation was now very serious, and became more so when news was flashed of the disaster at Nitral’s Nek, and they were ordered to retire. They could not retire and abandon the guns, yet the fire was so hot that it was impossible to remove them. Gallant attempts were made by volunteers from the Gordons — Captain Younger and other brave men throwing away their lives in the vain effort to reach and to limber up the guns. At last, under the cover of night, the teams were harnessed and the two field-pieces successfully removed, while the Boers who rushed in to seize them were scattered by a volley. The losses in the action were thirty-six and the gain nothing. Decidedly July llth was not a lucky day for the British arms.

It was well known to Botha that every train from the south was bringing horses for Lord Roberts’s army, and that it had become increasingly difficult for De Wet and his men to hinder their arrival. The last horse must win, and the Empire had the world on which to draw. Any movement which the Boers would make must be made at once, for already both the cavalry and the mounted infantry were rapidly coming back to their full strength once more. This consideration must have urged Botha to deliver an attack on July 16th, which had some success at first, but was afterwards beaten off with heavy loss to the enemy. The fighting fell principally upon Pole-Carew and Hutton, the corps chiefly engaged being the Royal Irish Fusiliers, the New Zealanders, the Shropshires, and the Canadian Mounted [449/4S0] Infantry. The enemy tried reiieatedly to assault the position, but were beaten back each time with a loss of nearly a hundred killed and wounded. The British loss was about sixty, and included two gallant young Canadian officers, Borden and Birch, the former being the only son of the minister of militia. So ended the last attempt made by Botha upon the British positions round Pretoria. The end of the war was not yet, but already its futility was abundantly evident. This had become more apparent since the junction of Hamilton and of Buller had cut off the Transvaal army from that of the Free State. Unable to send their prisoners away, and also unable to feed them, the Freestaters were compelled, before their own collapse, to deliver up in Natal the prisoners whom they had taken at Lindley and Roodeval. These men, a ragged and starving battalion, emerged at Ladysmith, having made their way through Van Reenen’s Pass. It is a singular fact that no parole appears on these and similar occasions to have been exacted by the Boers.

Lord Roberts, having remounted a large part of his cavalry, was ready now to advance eastward and give Botha battle. The first town of any consequence along the Delagoa Railway is Middelburg, some seventy miles from the capital. This became the British objective, and the forces of Mahon and Hamilton on the north, of Pole-Carew in the centre, and of French and Hutton to the south, all converged upon it. There was no serious resistance, though the weather was abominable, and on July 27th the town was in the hands of the invaders. From that date until the final advance to the eastward French held this advanced post, while Pole-Carew guarded the railway line. Rumours of trouble in the west had convinced Roberts that it was not yet time to [480/481] push his advantage to the east, and he recalled Ian Hamilton’s force to act for a time upon the other side of the seat of the war. This excellent little army, consisting of Mahon’s and Pilcher’s mounted infantry, M Battery R.H.A., the Elswick Battery, two 5-in. and two 4-7 guns, with the Berkshires, the Border Regiment; the Argyle and Sutherlands, and the Scottish Borderers, put in as much hard work in marching and in fighting as any body of troops in the whole campaign.

The renewal of the war in the west had begun some weeks before, but was much accelerated by the transference of Delarey and his burghers to that side. To attempt to give any comprehensive or comprehensible account of these events is almost impossible, for the Boer movements are still shrouded in mystery, but the first sign of activity appears to have been on July 7th, when a commando with guns appeared upon the hills above Rustenburg. Where the men or the guns came from is as difficult a problem as where they go to when they wish to disappear. It is probable that the guns are buried and dug up again when wanted. However this may be, Hanbury Tracy, Commandant of Rustenburg, was suddenly confronted with a summons to surrender. He had only 120 men and one gun, but he showed a bold front. Colonel Holdsworth, at the first whisper of danger, had started from Zeerust with a small force of Australian bushmen, and arrived at Rustenburg in time to drive the enemy away in a very spirited action. On the evening of July 8th Baden Powell took over the command, the garrison being reinforced by Plumer’s command.

The Boer commando was still in existence, however, and it was reinforced and reinvigorated by Delarey' s success at Nitral’s Nek. On July 13th they began to [481/482] close in upon Rustenburg again, and a small skirmish took place between them and the Australians. Methuen’s division, which had been doing very arduous service in the north of the Free State during the last six weeks, now received orders to proceed into the Transvaal and to pass northwards through the disturbed districts en route for Eustenburg, which appeared to be the storm centre. The division was transported by train from Kroonstad to Krugersdorp, and advanced on the evening of July 18th upon its mission, through a bare and fire-blackened country. On the 19th Lord Methuen manoeuvred the Boers out of a strong position, with little loss to either side. On the 21st he forced his way through Olifant’s Nek, in the Magaliesberg range, and so established communication with Baden-Powell, whose valiant bushmen, under Colonel Airey, had held their own in a severe conflict near Magato Pass, in which they lost six killed, nineteen wounded, and nearly two hundred horses. The fortunate arrival of Captain FitzClarence with the Protectorate Regiment helped on this occasion to avert a disaster.

Although Methuen came within reach of Eustenburg, he did not actually join hands with Baden-Powell. No doubt he saw and heard enough to convince him that that astute soldier was very well able to take care of himself. Learning of the existence of a Boer force in his rear, Methuen turned, and on July 29th he was back at Frederickstad on the Potchefstroom-Krugersdorp railway. The sudden change in his plans was caused doubtless by the desire to head off De Wet in case he should cross the Vaal River. Lord Roberts was still anxious to clear the neighbourhood of Eustenburg entirely of the enemy; and he therefore, since Methuen was needed to complete the cordon round De Wet, [487/488

recalled Hamilton’s force from the east and despatched it, as already described, to the west of Pretoria.

Before going into the details of the great De Wet hunt, in which Methuen’s force was to be engaged, I shall follow Hamilton’s division across, and give some account of their services. On August 1st he set out from Pretoria for Rustenburg. On that day and on the next he had brisk skirmishes which brought him successfully through the Magaliesberg range with a loss of forty wounded mostly of the Berkshires. On the 5th of August he had made his way to Eustenburg and drove off the investing force. A smaller siege had been going on to westward, where at Elands River another Mafeking man, Colonel Hore, had been held up by the burghers. For some days it was feared, and even ofificially announced, that the garrison had surrendered. It was known that an attempt by Carrington to relieve the place on August 5th had been beaten back, and that the state of the country appeared so threatening that he had been compelled to retreat as far as Mafeking, evacuating Zeerust and Otto’s Hoop. In spite of all these sinister indications the garrison was still holding its own, and on August 16th it was relieved by Lord Kitchener.

This stand at Brakfontein on the Elands River appears to have been one of the very finest deeds of arms of the war. The Australians have been so split up during the campaign, that though their valour and efficiency were universally recognised, they had no single large exploit which they could call their own. But now they can point to Elands River as proudly as the Canadians can to Paardeberg. They were only 400 in number on an exposed kopje, with 2,500 Boers round them, and no help near. Six guns were trained upon them, and during 11 days 1,800 shells fell within their [483/484] lines. The river was half a mile off, and every drop of water for man or beast had to come from there. Nearly all their horses and 75 of the men were killed or wounded. With extraordinary energy and ingenuity the little band dug shelters which are said to have exceeded in depth and efficiency any which the Boers have devised. Neither the repulse of Carrington, nor the jamming of their only gun, nor the death of the gallant Arnet, was sufficient to dishearten them. They were sworn to die before the white flag should wave above them. And so fortune yielded, as fortune will when brave men set their teeth, and Broadwood’s troopers, filled with wonder and admiration, rode into the lines of the reduced and emaciated but indomitable garrison. When the ballad-makers of Australia seek for a subject, let them turn to Elands River, for there was no finer fighting in the war. They will not grudge a place in their record to the 130 gallant Rhodesians who shared with them the honours and the dangers of the exploit.

On August 7th Ian Hamilton abandoned Eustenburg, taking Baden-Powell and his men with him. It was obviously unwise to scatter the British forces too widely by attempting to garrison every single town. For the instant the whole interest of the war centred upon De Wet and his dash into the Transvaal. One or two minor events, however, which cannot be fitted into any continuous narrative may be here introduced.

One of these was the action at Faberspruit, by which Sir Charles Warren crushed the rebellion in Griqualand. In that sparsely inhabited country of vast distances it was a most difficult task to bring the revolt to a decisive ending. This Sir Charles Warren, with his special local knowledge and interest, was able to do, and the success is doubly welcome as bringing additional [484/485] honour to a man who, whatever view one may take of his action at Spion Kop, has grown grey in the service of the Empire. With a column consisting mainly of colonials and of yeomanry he had followed the rebels up to a point within twelve miles of Douglas. Here at the end of May they turned upon him and delivered a fierce night attack, so sudden and so strongly pressed that much credit is due both to General and to troops for having repelled it. The camp was attacked on all sides in the early dawn. The greater part of the horses were stampeded by the firing, and the enemy’s riflemen were found to be at very close quarters. For an hour the action was warm, but at the end of that time the Boers fled, leaving a number of dead behind them. The troops engaged in this very creditable action, which might have tried the steadiness of veterans, were four hundred of the Duke of Edinburgh’s volunteers, some of Paget’s horse and of the 8th Kegiment Imperial Yeomanry, four Canadian guns, and twenty-five of Warren’s Scouts. Their losses were eighteen killed and thirty wounded. Colonel Spence, of the volunteers, died at the head of his regiment. A few days before, on May 27th, Colonel Adye had won a small engagement at Kheis, some distance to the westward, and the effect of the two actions was to put an end to open resistance. On June 20th De Villiers, the Boer leader, finally surrendered to Sir Charles Warren, handing over two hundred and twenty men with stores, rifles, and ammunition. The last sparks had been stamped out in the colony.

There remain to be mentioned those attacks upon trains and upon the railway which had spread from the Free State to the Transvaal. On July 19th a train was wrecked on the way from Potchefstroom to Krugersdorp without serious injury to the passengers. On [485/486] July 31st, however, the same thmg occurred with more murderous effect, the train running at full speed off the metals. Thirteen of the Shropshires were killed and thirty-seven injured in this deplorable affair, which cost us more than many an important engagement. On August 2nd a train coming up from Bloemfontein was derailed by Sarel Theron and his gang some miles south of Kroonstad. Thirty-five trucks of stores were burned, and six of the passengers (unarmed convalescent soldiers) were killed or wounded. A body of mounted infantry followed up the Boers, who numbered eighty, and succeeded in killing and wounding several of them.

On July 21st the Boers made a determined attack upon the railhead at a point thirteen miles east of Heidelberg, where over a hundred Koyal Engineers were engaged upon a bridge. They were protected by three hundred Dublin Fusiliers under Major English. For some hours the little party was hard pressed by the burghers, who had two field-pieces and a pom-pom. They could make no impression, however, upon the steady Irish infantry, and after some hours the arrival of General Hart with reinforcements scattered the assailants, who succeeded in getting their guns away in safety.

At the beginning of August it must be confessed that the general situation in the Transvaal was not reassuring. Springs near Johanneslmrg had in some inexplicable way, without fighting, fallen into the hands of the enemy. Klerksdorp, an important place in the south-west, had also been reoccupied, and a handful of men who garrisoned it had been made prisoners without resistance. Rustenburg was about to be abandoned, and the British were known to be falling back from Zeerust and Otto’s Hoop, concentrating upon Mafeking. The sequel proved however, that there was no cause for [486/487] uneasiness in all this. Lord Roberts was concentrating his strength upon those objects which were vital, and letting the others drift for a time. At present the two obviously important things were to hunt down De Wet and to scatter the main Boer army under Botha. The latter enterprise must wait upon the former, so for a fortnight all operations were in abeyance while the flying columns of the British endeavoured to run down their extremely active and energetic antagonist.

At the end of July De Wet had taken refuge in some exceedingly difficult country near Reitzburg, seven miles south of the Vaal River. The operations were proceeding vigorously at that time against the main army at Fouriesberg, and sufficient troops could not be spared to attack him, but he was closely observed by Kitchener and Broadwood with a force of cavalry and mounted infantry. With the surrender of Prinsloo a large army was disengaged, and it was obvious that if De Wet remained where he was he must soon be surrounded. On the other hand, there was no place of refuge to the south of him. With great audacity he determined to make a dash for the Transvaal, in the hope of joining hands with Delarey’s force, or else of making his way across the north of Pretoria, and so reaching Botha’s army. President Steyn went with him, and a most singular experience it must have been for him to be harried like a mad dog through the country in which he had once been an honoured guest. De Wet’s force was exceedingly mobile, each man having a led horse, and the ammunition being carried in light Cape carts.

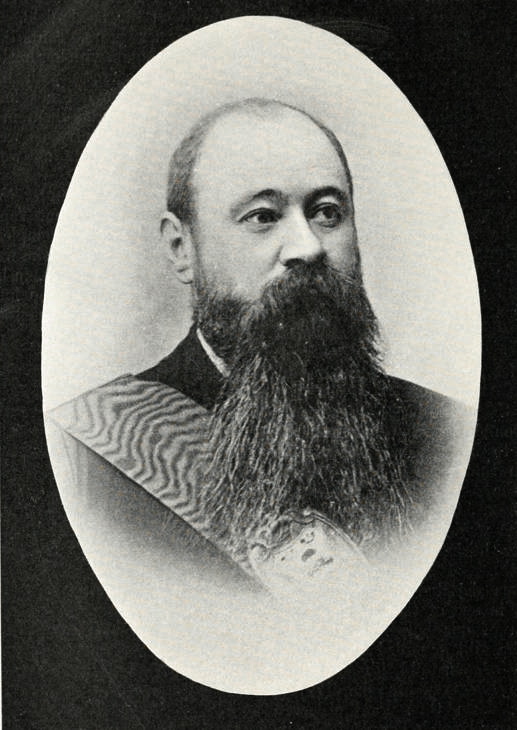

M. T. Steijn, President of the Orange Free State from Rompel’s Heroes of the Boer War. Click on image to enlarge it.

In the first week of August the British began to thicken round his lurking-place, and De Wet knew that it was time for him to go. He made a great show of fortifying a position, but it was only a ruse to deceive [487/488] those who watched him. Traveling as hghtly as possible, he made a dash on August 7th at the drift which bears his own name, and so won his way across the Vaal River, Kitchener thundering at his heels with his cavalry and mounted infantry. Methuen’s force was at that time at Potchefstroom, and instant orders had been sent to him to block the drifts upon the northern side. It was fomid as he approached the river that the vanguard of the enemy was already across and that it was holding the spurs of the hills which would cover the crossing of their comrades. But the dash of the Royal Welsh Fusiliers and the exertions of the artillery ridge after ridge was carried, but before evening De Wet with supreme skill had got his convoy across, and had broken away, first to the eastward and then to the north. On the 9th Methuen was in touch with him again, and the two savage little armies, Methuen worrying at the haunch, and De Wet snapping back over his shoulder, swept northward over the huge plains. Wherever there was ridge or kopje the Boer riflemen staved off the eager pursuers. Where the ground lay flat and clear the British guns thundered onwards and fired into the lines of wagons. Mile after mile the running fight was sustained, but the other British columns, Broadwood’s men and Kitchener’s men, had for some reason not come up. Methuen alone was numerically inferior to the men he was chasing, but he held on with admirable energy and spirit. The Boers were hustled off the kopjes from which they tried to cover their rear. Twenty men of the Yorkshire Yeomanry carried one hill with the bayonet, though only twelve of them were left to reach the top.

De Wet trekked onwards during the night of the 9th, shedding wagons and stores as he went. He was [488/489] able to replace some of his exliausted beasts from the farmhouses which he passed. Methuen on the morning of the 10th struck away to the west, sending messages back to Broadwood and Kitchener in the rear that they should bear to the east, and so nurse the Boer column between them. At the same time he sent on a messenger, who unfortunately never arrived, to warn Smith-Dorrien at Bank Station to throw himself across De Wet’s path. On the 11th it was realised that De Wet had succeeded, in spite of great exertions upon the part of Smith-Dorrien’s infantry, in crossing the railway line, and that he had left all his pursuers to the south of him. But across his front lay the Magaliesberg range. There are only three passes, the Magato Pass, Olifant’s Nek, and Commando Nek. It was understood that all three were held by British troops. It was obvious, therefore, that if Methuen could advance in such a way as to cut De Wet off from slipping through to the west he would be unable to get away. Broadwood and Kitchener would be behind him, and Pretoria, with the main British army, to the east.

Methuen continued to act with great energy and judgment. At three a.m. on the 12th he started from Fredericstadt, and by 5 p.m. on Tuesday he had done eighty miles in sixty hours. The force which accompanied him was all mounted, 1,200 of the Colonial Division and the Yeomanry with ten guns. Douglas with the infantry was to follow behind, and these brave fellows covered sixty- six miles in seventy-six hours in their eagerness to be in time. No men could have made greater efforts than did those of Methuen, for there was not one who did not appreciate the importance of the issue and long to come to close quarters with the wily leader who had baffled us so long. [489/490]

On the 12th Methuen’s van again overtook De Wet’s rear, and the old game of rearguard riflemen on one side, and a pushing artillery on the other, was once more resumed. All day the Boers streamed over the veldt with the guns and the horsemen at their heels. A shot from the 78th Battery struck one of De Wet’s guns, which was abandoned and captured. Many stores were taken and much more, with the wagons which contained them, burned by the Boers. Fighting incessantly, both armies traversed thirty-five miles of ground that day.

It was fully understood that Olifant’s Nek was held by the British, so Methuen felt that if he could block the Magato Pass all would be well. He therefore left De Wet’s direct track, knowing that other British forces were behind him, and he continued his swift advance until he had reached the desired position. It really appeared that at last the elusive raider was in a corner. But, alas for fallen hopes, and alas for the wasted efforts of gallant men! Olifant’s Nek had been abandoned and De Wet had passed safely through it into the plains beyond, where Delarey’s force was still in possession. Whose the fault, or whether there was a fault at all, it is for the future to determine. At least unalloyed praise can be given to the Boer leader for the admirable way in which he had extricated himself from so many dangers. On the 17th, moving along the northern side of the mountains, he appeared at Commando Nek on the Little Crocodile Kiver, where he summoned Baden-Powell to surrender, and received some chaff in reply from that light-hearted commander. Then, swinging to the eastward, he endeavoured to cross to the north of Pretoria. On the 19th he was heard of at Hebron. Baden-Powell and Paget had, however, already barred this path, and De Wet, having [490/491] sent Steyn on with a small escort, turned back to the Free State. On the 22nd it was reported that, with only a handful of his followers, he had crossed the Magaliesberg range by a bridle-path and was riding southwards. He had not been captured, but at least he could now do no serious harm to the British line of communications. Lord Roberts was at last free to turn his undivided attention upon Botha.

Two Boer plots had been discovered during the first half of August, the one in Pretoria and the other in Johannesburg, each having for its object a rising against the British in the town. Of these the former, which was the more serious, involving as it did the kidnapping of Lord Roberts, was broken up by the arrest of the deviser, Hans Cordua, a German lieutenant in the Transvaal Artillery. On its merits it is unlikely that the crime would have been met by the extreme penalty, especially as it was a question whether the agent provocateur had not played a part. But the repeated breaches of parole, by which our prisoners of one day were in the field against us on the next, called imperatively for an example, and it was probably rather for his broken faith than for his hare-brained scheme that Cordua died. At the same time it is impossible not to feel sorrow for this idealist of twenty-three who died for a cause which was not his own. He was shot in the garden of Pretoria Gaol upon August 24th. A fresh and more stringent proclamation from Lord Roberts showed that the British Commander was losing his patience in the face of the wholesale return of paroled men to the field, and announced that such perfidy would in future be severely punished.

Created 20 December 2013