Doubtless the idea of visiting America had fascinated Dickens ever since

the early 1830s, when Mrs. Trollope

published her Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832): he

probably alludes to in The Pickwick

Papers (1836-7), Chapter 45, when Tony Weller suggests that to avoid prison

Mr. Pickwick should escape to America, and afterwards write a book "as'll pay all his

expenses and more, if he blows 'em up enough." Eventually Dickens himself made the trip.

Principally relying upon his voluminous correspondence to his friend and business manager

John Forster, but also referring to letters he had sent to other

friends between late January and early June, 1842, Dickens gives a detailed account of

his voyage out on the steamship Britannia (3 January through 22

January 1842), and of his travels by rail and boat through New England, Ohio, southern

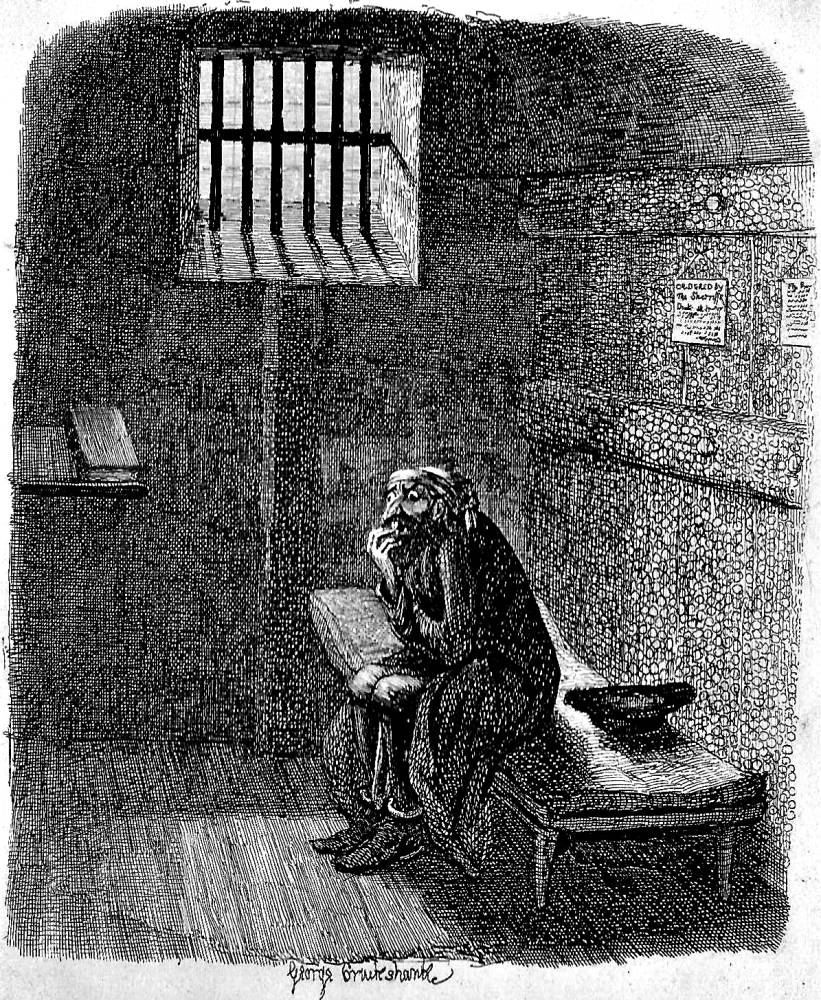

Ontario, and Quebec. Marcus Stone added four psychologically telling full-page composite

woodblock engravings for the Library Edition (1874), including

The Emigrants (frontispiece) and

The

Solitary Prisoner.

Doubtless the idea of visiting America had fascinated Dickens ever since

the early 1830s, when Mrs. Trollope

published her Domestic Manners of the Americans (1832): he

probably alludes to in The Pickwick

Papers (1836-7), Chapter 45, when Tony Weller suggests that to avoid prison

Mr. Pickwick should escape to America, and afterwards write a book "as'll pay all his

expenses and more, if he blows 'em up enough." Eventually Dickens himself made the trip.

Principally relying upon his voluminous correspondence to his friend and business manager

John Forster, but also referring to letters he had sent to other

friends between late January and early June, 1842, Dickens gives a detailed account of

his voyage out on the steamship Britannia (3 January through 22

January 1842), and of his travels by rail and boat through New England, Ohio, southern

Ontario, and Quebec. Marcus Stone added four psychologically telling full-page composite

woodblock engravings for the Library Edition (1874), including

The Emigrants (frontispiece) and

The

Solitary Prisoner.

Although the question of international copyright and numerous public receptions consumed much of his time in America, before his departure for home from the port of New York on 7 June, he had visited a number of factories, and public institutions such as hospitals, asylums, and prisons, and had observed enough about the living and working conditions of slaves to take an abolitionist stance.

By the time of his tour of Philadelphia's "solitary prison," the Eastern Penitentiary, Dickens had acquired through personal experience a considerable first-hand knowledge about the subject of incarceration, since his father had been kept in London's infamous Marshalsea Prison (demolished in 1842) for non-payment of debts in 1824. Moreover, Dickens had published an account of a visit to London's Newgate Prison in Sketches by Boz (1835), Chapter 32. In America, he had already visited the Boston House of Correction and New York City's Tombs, and afterwards visited Maryland's State Penitentiary. Given his personal background knowledge of the subject, then, it is not surprising that prisons and prisoners should be a staple of his fiction from Barnaby Rudge (1841) through Great Expectations (1861), and that the Bastille and its solitary prisoner, Dr. Manette, should figure so prominently in the plot of A Tale of Two Cities (1859).

The title American Notes for General Circulation involves a topical allusion to the counterfeiting of notes issued by private banks in the United States, and therefore the general untrustworthiness of such accounts as had recently been published by James Silk Buckingham, Capt. Frederick Marryat, and Harriet Martineau. Dickens may also be poking fun at his own reliability as a witness to the culture of the new republic. Returning to England in June, 1842, Dickens quickly assembled the travel-book, and published it early in October 1842. "Especially in the USA in pirated editions," notes Paul Schlicke in the Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens, the travelogue proved a best-seller, "but the notices even in England were disappointing" (20) because the subject matter was "far from novel"and "his impressions not sufficiently 'Dickensian'." Only those with Abolitionist sentiments among his American reviewers responded positively.

"The Solitary System" which Dickens witnessed in operation at the Eastern Penitentiary on 8 March 1842 seems to have made a lasting impact on the novelist. The essay in which he exposed the evils of the solitary system became the seventh chapter in American Notes. Dickens had visited Philadelphia's Eastern Penitentiary to see the progressive system of prison discipline often called "The Panopticon System" of political philosopher Jeremy Bentham because it facilitated the scrupulous monitoring of individual prisoners in private cells. As his letter to John Forster back in London foreshadowed, Dickens almost at once denounced the separate system as cruel and unusual punishment. As the following excerpts reveal, Dickens sought to have his reader enter the prisoner's rigidly-controlled world, to give the incarcerated a voice, and to describe the stages of psychological trauma that the solitary prisoner would endure throughout his sentence. Ironically, Dickens had previously eulogized the "silent system" instituted in England's Coldbath Fields and Tothill Fields Prisons, which had instituted it to replace the common lockup and exercise yard because this progressive system would discourage recidivism and reduce costs.

His denunciation of this system at Philadelphia immediately angered British leaders of penal reform. For example, John Field, the chaplain of Reading Gaol, in Prison Discipline and the Advantages of the Separate System of Imprisonment. A Detailed Account of the Discipline in the New County Gaol (1848), accused Dickens of having written sheer fiction when he described the system.

The Visitor's Experience of The Solitary System

The cells of three solitary prisoners whom Dickens visited at the Eastern State Penitentiary on 8 March 1842 were oppressive in their isolation. In his essay "Philadelphia, and its Solitary Prison" Dickens makes clear his concern that the much-vaunted "Solitary" or "Silent System" will lead to psychological breakdown.

In another cell, there was a German, sentenced to five years' imprisonment for larceny, two of which had just expired. With colours procured in the same manner, he had painted every inch of the walls and ceiling quite beautifully. He had laid out the few feet of ground, behind, with exquisite neatness, and had made a little bed in the centre, that looked, by-the-bye, like a grave. The taste and ingenuity he had displayed in everything were most extraordinary; and yet a more dejected, heart-broken, wretched creature, it would be difficult to imagine. I never saw such a picture of forlorn affliction and distress of mind. My heart bled for him; and when the tears ran down his cheeks, and he took one of the visitors aside, to ask, with his trembling hands nervously clutching at his coat to detain him, whether there was no hope of his dismal sentence being commuted, the spectacle was really too painful to witness. I never saw or heard of any kind of misery that impressed me more than the wretchedness of this man.

That it is a singularly unequal punishment, and affects the worst man least, there is no doubt. In its superior efficiency as a means of reformation, compared with that other code of regulations which allows the prisoners to work in company without communicating together, I have not the smallest faith. All the instances of reformation that were mentioned to me, were of a kind that might have been — and I have no doubt whatever, in my own mind, would have been — equally well brought about by the Silent System. With regard to such men as the negro burglar and the English thief, even the most enthusiastic have scarcely any hope of their conversion.

It seems to me that the objection that nothing wholesome or good has ever had its growth in such unnatural solitude, and that even a dog or any of the more intelligent among beasts, would pine, and mope, and rust away, beneath its influence, would be in itself a sufficient argument against this system. But when we recollect, in addition, how very cruel and severe it is, and that a solitary life is always liable to peculiar and distinct objections of a most deplorable nature, which have arisen here, and call to mind, moreover, that the choice is not between this system, and a bad or ill-considered one, but between it and another which has worked well, and is, in its whole design and practice, excellent; there is surely more than sufficient reason for abandoning a mode of punishment attended by so little hope or promise, and fraught, beyond dispute, with such a host of evils.

The only visual and tactile stimulations that the ESP [Eastern State Penitentiary] Solitary System would afford the inmate were his blanket, a pillow, a hand-hooked mat, and his shoe-making equipment, all of these being manifestations of the system's Quaker origins. The ESP's intention was, first and foremost, to discourage recidivism or the repeating of criminal offences. Thus, inmates did not have the usual recourse to socialisation with other inmates in communal lockups and exercise yards, both long having been features of such British prisons as Newgate, which Dickens as a young reporter had visited. Everything in the ESP was intended to encourage the inmate through penitence and thoughtful reflection to become a productive citizen of the Republic upon his release, applying his newly acquired vocational skills for the good of the American economy.

Dickens, Prisoners, and Prisons: Pickwick to A Tale of Two Cities — A Rogues’ Gallery

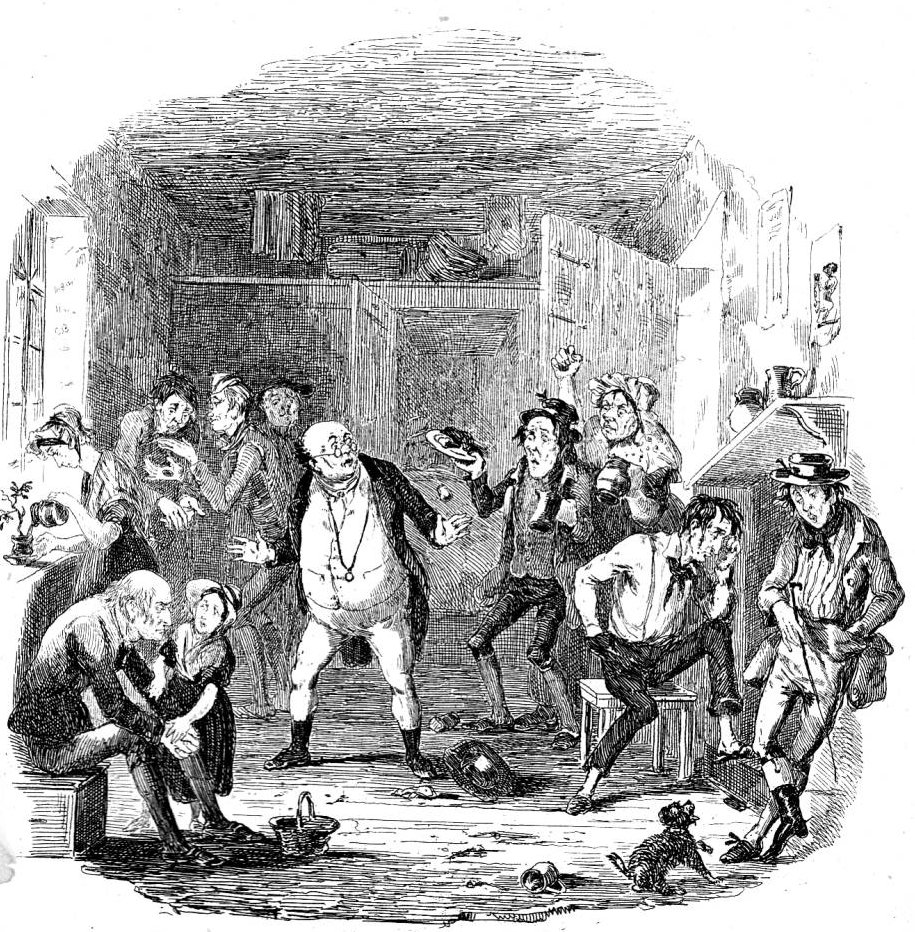

The following illustrations of various Dickens prisoners contrast the traditional lockup, which permitted socialisation of inmates, with the new system of "Solitary Confinement."

Harry Furniss, The Solitary Prisoner (1910). Fagin in the Condemned Cell from Oliver Twist by George Cruikshank (Nov., 1838).

Hablot Knight Browne ('Phiz'), In The Bastille (1859). Released from The Bastille from Harper's Weekly by John McLennan (7 May 1859).

Dickens’s Socialized Prisoners

Left: Felix Octavius Carr Darley, “A Visit to Newgate” from Sketches by Boz, Vol. I (1865). Centre: Hablot Knight Browne, “The Brothers” from Little Dorrit (Part 10: May 1856). Right: Hablot Knight Browne, “The Discovery of Jingle in the Fleet” from Pickwick Papers (July 1837).

Breezy Humour rather than Social Commentary in the American Household Edition

Thomas Nast, Philadelphia in the Harper & Bros. Household Edition of American Notes, Chapter VII (1877).

For the Harper and Brothers’ version of the Household Edition, New York political cartoonist Thomas Nast (1841-1907) rarely offers a psychological study in the socially realistic manner of such sixties illustrators as Marcus Stone, whose prisoner mentally collapsing in the "Solitary System" of Philadelphia's Eastern Penitentiary grimly reminds us that young Dickens saw himself as a political reformer (Radical) and social critic. Certainly such an in-depth examination of the prisoner's derangement would not have been congenial to Nast's inventiveness and lively comic sense. Instead, then, Nast for the American Household Edition imagines a pedestrian (perhaps even Dickens himself) gingerly trying to avoid all the water accumulating on the sidewalks from the washing of steps and windows by African-American household servants on the tree-lined streets of Philadelphia. Other illustrators, in contrast, have focussed on the evils of the "Silent System" of Britain's Pentonville Prison, Reading Gaol, and Belfast's Crumlin Road Prison as adapted by American penal authorities in the City of Brotherly Love.

Related Material

- Text of Charles Dickens's "Philadelphia, and its Solitary Prison"

- Reading and Discussion Questions

- The Panopticon System: Machines That Make Machines

- Designing the Workhouse

Images scanned by the author [You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the author and (2) link your document to this URL or cite it in a print document.]

Bibliography

Bailey, Victor. “Part 7. Silent and Separate Systems of Prison Discipline.” Chapter 40. Charles Dickens, “On the Eastern Penitentiary, Philadelphia,” American Notes, 1st published in 1842. Nineteenth-Century Crime and Punishment. Vol. 3, Prisons and Prisoners. London and New York: Routledge, 2022. Pp. 1-19.

Darley, Felix Octavius Carr. “A Visit to Newgate.” Frontispiece for Dickens’s Sketches by Boz, Volume 1. New York: Sheldon and Company, 1865.

Davis, Paul. Charles Dickens A to Z: The Essential Reference to His Life and Work. New York: Checkmark and Facts On File, 1998.

Dickens, Charles. American Notes for General Circulation and Pictures from Italy. The Illustrated Library Edition. Illustrated by Marcus Stone. London: Chapman & Hall, 1874.

Dickens, Charles. American Notes and Pictures from Italy, Volume 20, in the New York: P. F. Collier & Son edition, n. d.

Furniss, Harry (illustrator). “The Solitary Prisoner.” Frontispiece for Dickens’s American Notes and Pictures from Italy. Charles Dickens Library Edition. London: Educational Book, 1910. Vol. 13.

Nast, Thomas. (illustrator). Dickens’s Pictures from Italy and American Notes for General Circulation. Household Edition. New York: Harper and Brothers, 1877.

Schlicke, Paul. The Oxford Reader's Companion to Dickens. Oxford: Oxford U. P., 1999.

Stone, Marcus. “The Solitary Prisoner.” Chapter 7, “Philadelphia and Its Solitary Prison.” Dickens’s American Notes for General Circulation. Illustrated Library Edition. London: Chapman and Hall, 1874. Facing p. 124.

Created 7 July 2004

Last modified 26 January 2026