Oliver Twist was ready made for the stage adapters, who merely excised the social criticism and cut down the plot until it encompassed only the main scenes and characters — although, even in this truncated form, the dramas of Oliver Twist (and indeed of most of Dickens's novels) were generally taken to be extremely "realistic" and not "melodramatic." — Peter Ackroyd, p. 276

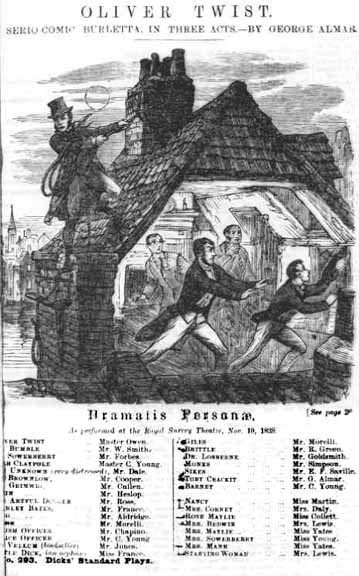

The earliest known playbill of an “Oliver Twist” production

One of the most popular — and sensational — melodramas on nineteenth-century British stages was not an original play, but an adaptation or series of adaptations of Dickens's second novel, which continued to be a best-seller long after the author's death in 1870. Its nineteenth-century stage history, which (according to Bolton), includes over two hundred separate productions, follows the pattern of other adaptations for the stage of Dickens novels: an initial surge of popular interest while novel was appearing in serial form resulted in numerous stage versions by various theatrical pirates who paid no royalties; then a decline in productions in the years following initial volume publication; and finally a second generation of adaptations that took into account both the novel itself and the previous adaptations. In Oliver Twist, moreover, "hack playwrights found in the novel everything they needed to appeal to their audience already written in a form that could be shifted to the dramatic medium with a minimum of effort or talent" [Fulkerson, 83]. The prolific theatrical pirate

Edward Stirling, of course, wrote a version of Oliver, and this was presented in the same season at the City of London Theatre, while a version by C. Z. Barnett was put on at the Royal Pavilion, Whitechapel, a theatre in which the Yates-Gladstane management had an interest, on May 21 [1838]. Then came George Almar's production at the Surrey Theatre on November 19, and many provincial tours. Almar had the advantage over his predecessors of coming late into the field, thus having the dramatic tour de force, the murder of Nancy by Bill Sikes, to play with. This episode had appeared in the Oliver Twist instalment of October, 1838, and was swiftly transferred to the stage with gruesome effect. [Dubrez Fawcett, 54]

(In fact, since Nancy's death occurs in serial instalment no. 21 [January 1839] and since Sikes dies by inadvertence in no. 22 [February 1839], the Bentley triple-decker, published in November 1838 and not Bentley’s Miscellany, must have been the source of these sensational events in George Almar's adaptation. Morley may be incorrect about the "gruesome effect" since Almar's script specifies that Nancy is murdered offstage.)

Dickensian theatre-historian Malcolm Morley notes that, like the jovial Mr. Pickwick, the oppressed waif Oliver found himself on the London stage well before his tale was fully told, although Dickens's project to act as the adaptor for a production at The Adelphi under Frederick Yatescame to nothing. However, on Tuesday, March 27th, 1838, almost a year before the story's serial conclusion in Bentley's Miscellany, the 1200-seat St. James's Theatre (the venue for Dickens's own early plays The Strange Gentleman, The Village Coquettes, and Is She His Wife?) mounted two performances of a script that has not survived. Although its author cannot be definitively identified, Morley conjectures that the dramatist was Dickens's friend and founder of Punch Gilbert Abbot à Beckett, who was both acting-manager and resident adaptor at The St. James's. That it lasted at most two nights suggests that it was not well received by the middle-class audience at the up-and-coming suburban theatre. Designed by Samuel Beazley for tenor and actor-manager John Braham, this small playhouse had opened on 14 December 1835. Dickens's The Village Coquettes, a two-act sentimental/comic operetta set in the year 1829, was presented as a "burletta" at St. James's Theatre on 6 December 1836, starring tenor John Braham as Squire Norton, John Pritt Harley as Martin Stokes, and Elizabeth Rainforth as Lucy Benson. Oliver Twist, however, was not successful at the St. James's, even though the cast was not undistinguished: the celebrated Mrs. Stirling as Nancy, Henry Hall as Sikes, Edward Wright, J. Webster, Alfred Wigan, Hart, Mrs. Seymour, and Miss Allison, with the manager himself enacting the part of Bumble.

What, however, is to be said against such criticisms as the following, all taken from contemporary journals?

Actors by Daylight: "a very meagre and dull affair and the sooner taken from the [theatre's play]bills the better"; The Literary Gazette: "a thing more unfit for any stage, except that of a Penny Theatre, we never saw"; and from another magazine: "It was consigned by the audience to the lower depths of Tartarus". [Morley 75]

(Morley speculates that, given Dickens's close connection to The St. James's, he would have known about the production, and may even have served as a consultant for the manager, Harley.)

The second stage debut of young Oliver occurred in C. Z. Barnett's Oliver Twist, or, The Parish Boy's Progress at the Pavilion Theatre, Mile End Road, on 21-26 May 1838. Without the conclusion of the story known to its adaptor, however, this version did not prove a palpable hit for the managers, Frederick Yates and Gladstone. However, the third version, by comedian George Almar, which premiered on 19 November 1838 at the Surrey (with both John Forster and Charles Dickens in a box), proved to be one of the most enduring theatrical adaptations of the nineteenth century, with a slightly different version staged at New York City's Winter Garden and subsequently published by Samuel French.

In an era when there were no matinees (for the working-class could ill-afford to take an afternoon off in the 1830s), when most people walked rather than drove or rode, when omnibuses carried workers to and from their shops and businesses only, when a theatre survived or went into bankruptcy based on its ability to serve its local community, The Royal Surrey's production of Oliver Twist, the first to include both the murder of Nancy and the death of Sikes, did phenomenally well. In advertising his performance as Oliver, Master Owen later asserted that he had performed the role for "150 nights before 600,000" (cited in Dubrez Fawcett, 55) theatre-patrons.

Generally the character was taken by an actress [e. g., Mrs. Honner in the 1838-38 production at Sadler's Wells], and not always to the novelist's satisfaction. His own words were, "If it be played by a female it should be a very sharp girl of thirteen or fourteen, not more, or the character would be an absurdity." [Morley 78]

The cast were veterans of Surrey-side melodramas: character actor Heslop played Fagin; E. F. Saville, hero of many a transpontine drama, played Sikes; Ross took the Artful Dodger, the comedian W. Smith played Bumble, and the popular comedian-dramatist George Almar gave himself the "comic man" role of "Flash" Toby Crackit, much expanded in his "serio-comic burletta." And the melodramatic adaptation was highly appropriate for the stage of The Royal Surrey Theatre, a working-class venue famous for vastly popular and lucrative productions of the transpontine melodrama by Douglas Jerrold, Black-Eyed Susan; or, All in the Downs, in 1829, and Edward Fitzball's thriller Jonathan Bradford; or, The Murder at the Roadside Inn, in 1833. Almar's adaptation, the first to incorporate the whole story, comprising three acts and thirty-one scenes, concludes with the sensational death of Sikes rather than Fagin's execution or Oliver's contemplation of his mother's memorial.

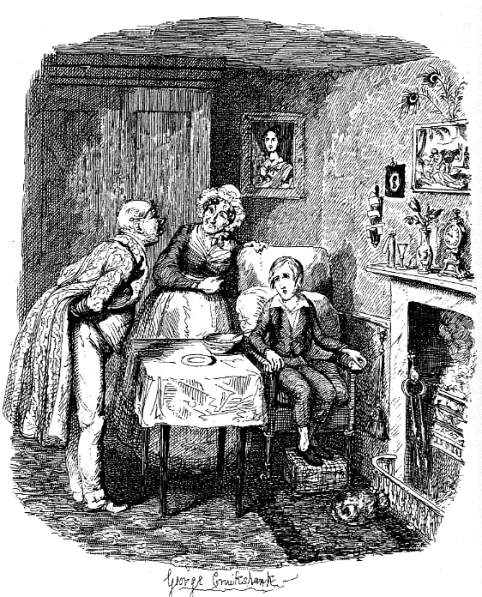

Left: Oliver Plucks up a Spirit. Right: Oliver Recovering from the Fever. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

Martin Meisel notes that, despite the abrupt cut to Oliver's apprenticeship at Sowerberry's funeral parlour, Almar follows the order of the Cruikshank illustrations from Oliver Plucks up a Spirit into the second act,

and some of the best dramatic pictures [i. e., theatrical tableaux] come directly from the text. So, for example, though Cruikshank's Oliver Recovering from the Fever [originally, August 1837] in the house of Mr. Brownlow is fully realized at the opening of Act II as a discovered tableau, the scene ends with the much more effective and situational tableau, not to be found among the plates, of Grimwig and Brownlow, who "each sink into their chairs, with their eyes fixed attentively on the watch upon the table between them" as they await Oliver's return from his errand of trust. [Meisel, 254]

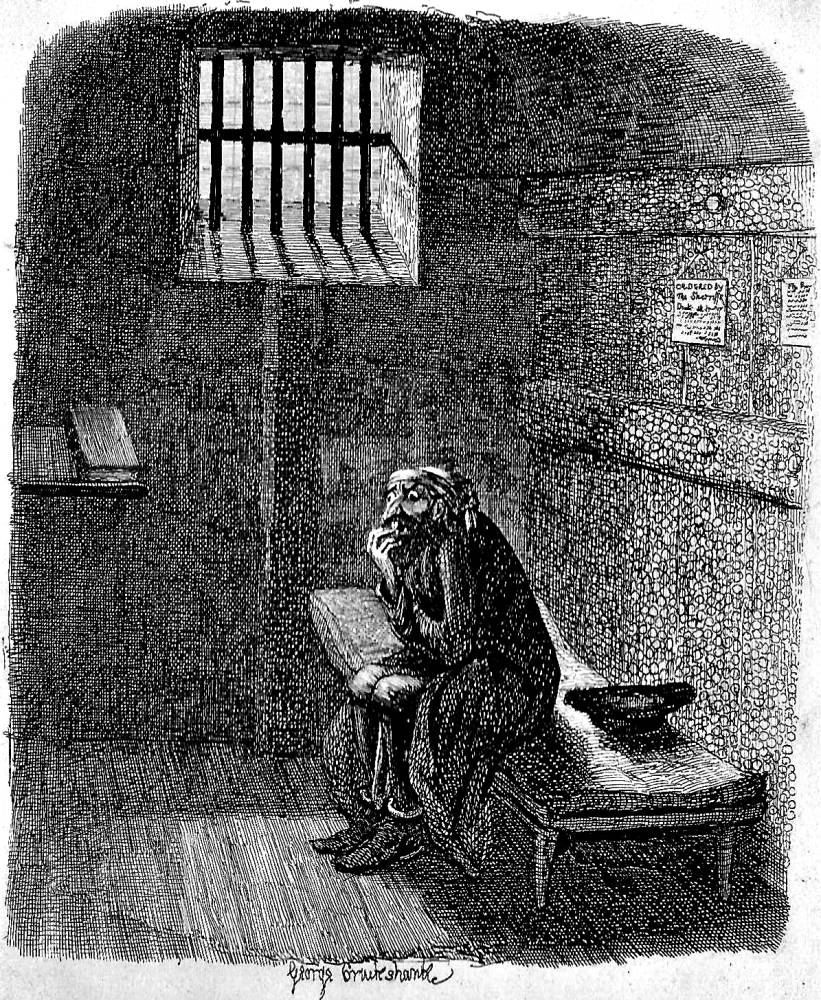

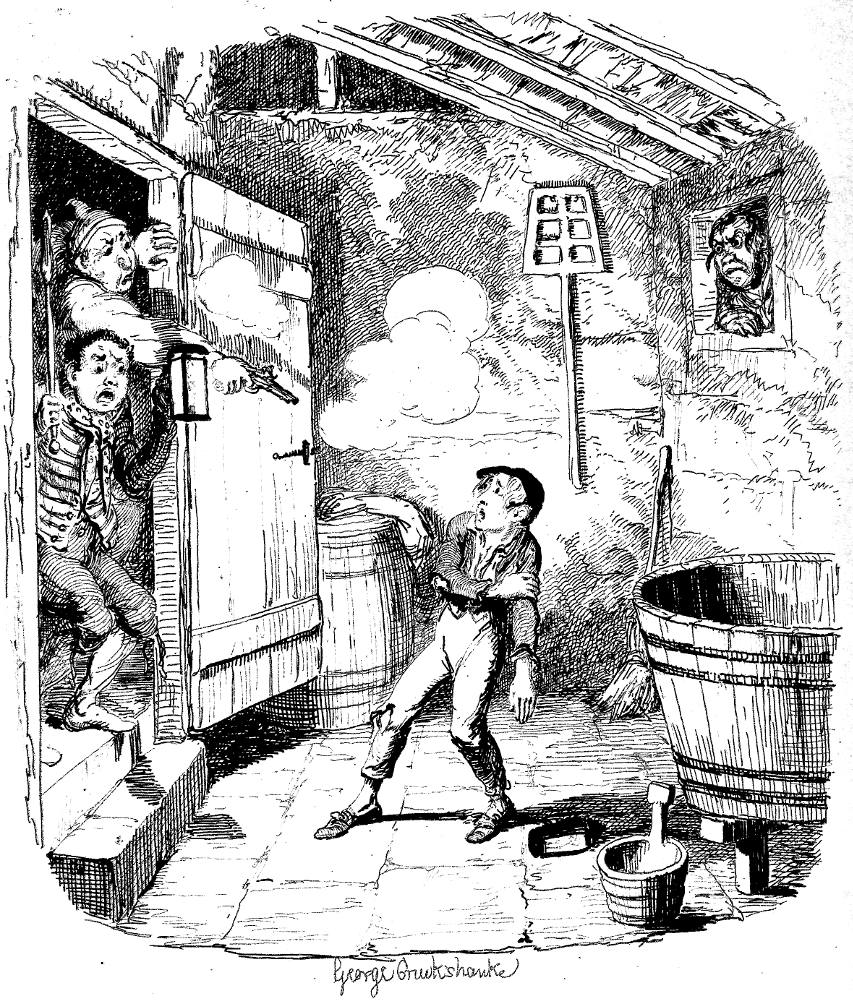

Left: Fagin in the condemned Cell. Right: The Burglary. [Click on images to enlarge them.]

In the second half of the play, perhaps in order to advance the action, Almar does not rely as heavily on tableaux from the Cruikshank engravings, and even replaces the now-famous Fagin in the condemned Cell with Fagin soliloquizing about a terrible dream just prior to his apprehension, thereby placing the emphasis on the scene in which Sikes dies by inadvertance as a demonstration of the power of Divine Justice. Having reversed the perspective in his dramatisation of The Burglary by showing the scene from outside the brewhouse, in this culmination of the Sikes plot, Almar

resolves the problem of uniting inside and outside in the sensation scene near the very end of the play. This is the scene in which Sikes, exposed and pursued by the aroused virtue of Charley Bates, providentially hangs himself, and (in the novel only) is joined by his abused dog in death. The scene begins in "The interior of an old house situated on Jacob's Island with a view of the Thames by moonlight," and Toby Crackit playing cribbage with Charlie [sic] Bates [in the four-act American and three-act Lacy editions, the script identifies the card-players as The Dodger and Toby, likely because in the original play The Dodger has not been sentenced to transportation prior to this scene]. It ends both inside "he sets his foot against a stack of chimneys, fastens one end of the rope firmly round it" (as in Cruikshank's plate), makes a running noose, gets it over his head, and sees Nancy's eyes. . . . . Cruikshank more conventionally separates outside from inside in his poetic image of Sikes and his dog on the rooftops. [Meisel 256]

Although the illustration of the cutaway set would have been somewhat odd as a book illustration, as the Dicks cover-plate it is effective in recalling the most powerful scene in the Almar script. The artist for the Acting National Drama, cover, by the way, Meisel gives as Pierce Egan, the Younger.

In an era in which many a play closed after just two nights, Almar's highly pictorial adaptation, produced by William Davidge (1815-89), had an initial run of 86 performances (19 November 1838 through 21 June 1839), perhaps a testimonial to its fidelity to Cruikshank, if not to Dickens. Omitting the workhouse scenes entirely for the sake of economy, Almar opens with Bumble in soliloquy announcing that Oliver has been apprenticed to an undertaker. After several scenes set in Mr. Sowerberry's establishment, Oliver, escorted by The Dodger and Charley Bates, arrives at Fagin's den, where he witnesses the master-thief crack a whip to bring his charges into line. Proceeding generally according to the events in the novel, the play is particularly effective because it successfully uses Oliver to evoke pathos through the early apprenticeship and underworld scenes. Although simplified for the stage, Fagin (Heslop) and Nancy (Miss Martin) are foils in the villain's growing love of deceit (in league with Monks, without taking his confederates into his confidence) and her moral conflict over whether to remain loyal to Bill (E. F. Saville) or to assist Rose Maylie in saving Oliver. Thus, as Fulkerson remarks, "the adaptor was able to transfer to the stage Nancy’s fairly complex motivation, her anguish, and her innate humaneness despite the life she leads—attributes which together make her an essentially credible and sympathetic creation in the romantic mould" (87). The deaths of the reformed Nancy and then of the "savage" and "reckless" Sikes, although consistent with Dickens’s text, are nevertheless gripping in Almar’s adaptation. On page 8, Almar entitles the synopsis of the scene in Sikes's garret "The Murder — Fatal Consequences," as if to suggest that both are repaid by Nemesis for their ill-treatment of Oliver. "The man struggled violently to release his arm, but those of the girl were clasped around his, and he could not tear them away." The dialogue is terse as Sikes, under Fagin's influence, is deaf to Nancy's pleas.

Act III, Scene VI: Sikes's garret, as before.

NANCY discovered asleep on the bed. Music. Enter Sikes, L. door, he puts out the light on the table.

Sikes (rouses Nancy): Get up.

Nancy (rises): Is that you, Bill? Oh, I'm so glad! but you’ve put out the candle.

Sikes: There's light enough for what I've got to do.

Nancy: I'll open the window.

Sikes: Stay where you are; I want you (seizes her)

Nancy: Oh, tell me what I've done. I won't scream or cry out. What's the matter?

Sikes: You know well enough; you’ve been watched tonight; I know all about it.

Nancy: Then spare my life, as I spared yours. Oh, you cannot have the heart to kill me. I will not loose my hand till you say, you forgive me.

Sikes: Let go, will you?

Nancy: Stop and hear me, Bill — I have been true to you — I have, upon my guilty soul.

Sikes: It's a lie.

Nancy: No, it's the truth. The good lady and gentleman told me of a home where I could end my days in peace. Let me see them again, and beg them to show the same mercy to you; we will lead better lives, and forget how wicked we have been — It is never too late to repent — never — never.

Sikes: Will you let go?

Nancy: No, never, not till you say you forgive me.

Sikes: Then die.

(strikes her with pistol — a fearful struggle ensues — and drags her off, R., a pistol shot is heard — a pause, and SIKES re-enters trembling, he falls on the bed — a groan is heard, he starts up, goes to the R. door, looks off, staggers across and exits, L. D.) [Almar, T. H. Lacy, p. 44]

Although Almar specifically directs that his Sikes murder Nancy off-stage, in the September 1842 Old Vic production mounted by Osbaldistone, transpontine character actor E. F. Saville reprising his role as Sikes (now "Sykes") played to the audience like some sort of proletarian Richard the Third — and took the life of Nance (Miss Martin from the original Almar production) with much blood-letting on stage:

The 'murder of Nancy' was the great scene. Nancy was always dragged round the stage by her hair, and after this effort Sikes always looked up defiantly at the gallery, as he was doubtless told to do in the marked prompt copy. He was always answered by one loud and fearful curse, yelled by the whole mass like a Handel Festival chorus. The curse was answered by Sikes dragging Nancy twice around the stage, and then, like Ajax [in The Iliad], defying the lighting. The simultaneous yell then became louder and more blasphemous. Finally, when Sikes, working up to a well rehearsed climax, smeared Nancy with red-ochre, and taking her by the hair (a most powerful wig) seemed to dash her brains out on the stage, no explosion of dynamite invented by the modern anarchist, no language ever dreamt of in Bedlam could equal the outburst. [John Hollingshead, My Lifetime, 1895, I, 189-190; cited in Fulkerson, 88]

But precisely which adaptation of the novel did Hollingshead witness on stage at the Royal Victoria Theatre? Although the actor and actress were the very same as in the original Almar production (i. e., E. F. Saville as Sikes, Miss Martin as Nancy), the George Almar script does not actually show the murder of Nancy as occurring on stage, so that the playwright was not necessarily Almar. Philip Bolton in Dickens Dramatized lists the adaptor responsible as "anon" (116), but it is possible that the 1842 script was merely a re-working of Almar's 1838 script, which even in its American iteration (New York: Samuel French) for the March 1861 production does not involve Nancy murdered before the audience. Lacy No. 33, published in 1842, likewise omits an on-stage murder. The "vamping up" of old scripts was a common enough practice; for example, the March 1840 version that ran at The Royal Theatre, Edinburgh, ostensibly by William Henry Murray, was "Specially adapted for this theatre" (C. J. Dibdin; cited in Bolton, 115), and therefore may well have been a revision of the Almar script, which was the basis for the January-February 1841 production at Sheffield. Saville and Morelli (Fagin) appeared in the May 1843 revival at The Royal Victoria, so that Hollingshead's comments may concern this production.

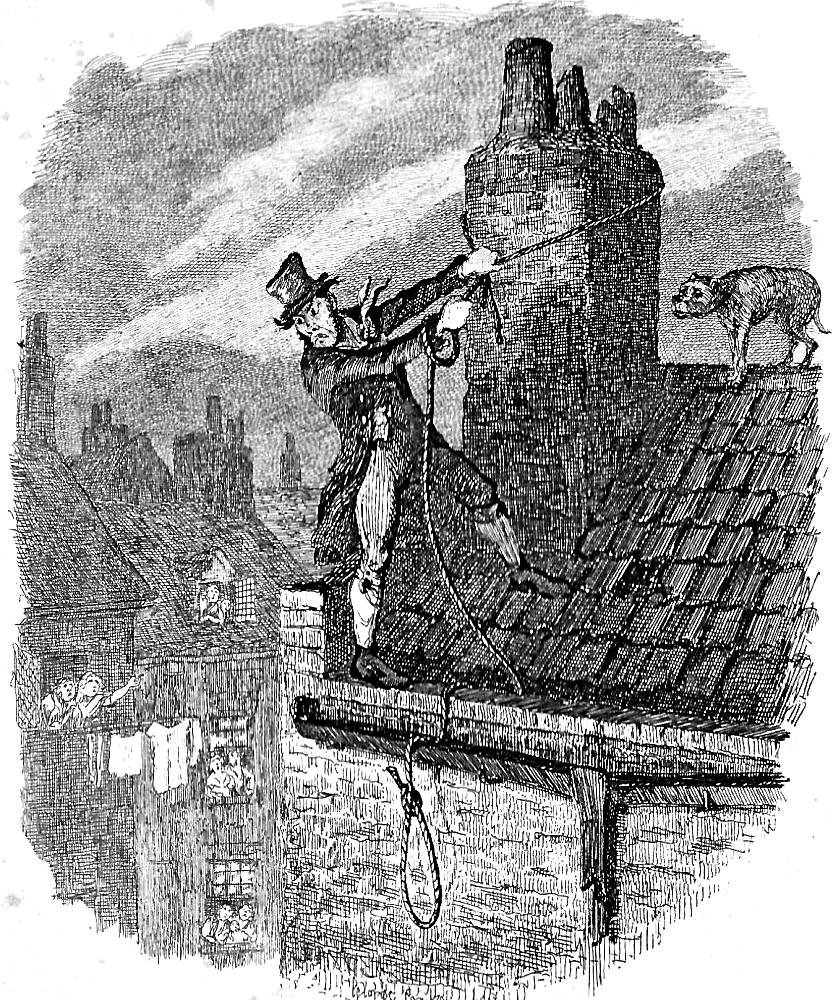

In Almar's final scene in the Samuel French version, the dramatist realizes the George Cruikshank illustration The Last Chance (Part 22, February 1839; originally published in the third volume of the Richard Bentley publication, November 1838):

MR. BROWNLOW. (without L. U. E.) Open, in the king's name.

TOBY. Do you hear, Bill?

SIKES. Is the door down stairs fast?

TOBY. Double locked and chained, and the panels lined with sheet iron.

SIKES. (shaking his fist over the wall, L. C.) Then damn you all, do your worst &mdasah; I'll cheat you yet.

MR. B. (without) Twenty guineas to the man who brings a ladder.

TOBY. Quick, Bill, or you'll be nabbed! Exit into room, R.

SIKES. Ah! here's a coil of rope! (takes one up) By the window I can lower myself down to the ditch, and then may the devil aid me (music — gets out of window to the roof of house — loud yells, when he is seen by the mob, L. — SIKES shakes his fist at them, is seen to fasten one end of rope round chimney, and form a noose at the other) I can let myself down to within a a few feet of the ground, and then cut the rope &mdasah; stop! I will put it for a moment round my neck till I fasten it under my armpits. [He puts loop over his head.] Now Nancy! Ah, those eyes again! Hell! I have fallen!

[In turning his head he staggers and is precipitated from roof, the rope tightens and he is left hanging, the mob below shouting He has hanged himself! — Others overcome TOBY. — Picture. [alluding to the Cruikshank illustration The Last Chance]

The Lacy version of the text adds the following directions, and an epilogue spoken by Brownlow, acting as a chorus to articulate the workings of poetic justice:

Loses his footing and falls from roof, loud cheers and clapping of hands when he falls—at the same moment the door, L. 2 E. is burst open, OFFICERS enter, with BROWNLOW, OLIVER, ROSE MAYIE, MR. GRIMWIG, &c.

MR. B. The murderer has met his death, hung by his own bloodthirsty hands, and poor Nancy is avenged. Oliver, dear son of my only brother, your trials are over; your enemies vanquished, and a happy life is opening before you.

OLIVER. How can I thank you, sir? Words cannot convey to you the gratitude I feel towards you, and the kind friends who have befriended the poor orphan Parish Boy — Oliver Twist! [Curtain]

Epilogue

Below: The title-page of Oliver Twist: Serio-comic Burletta in Three Acts. George Almar's dramatic adaptation of Dickens's Oliver Twist. Dick's Standard Plays 293. First performed at The Royal Surrey Theatre, 19 November 1838. Scene illustrated on cover and title-page: In turning his head, [Sikes] staggers and precipitated from the roof, the rope tightens and he is left hanging, the mob below shouting "He has hanged himself" — others overcome Toby. Picture. (end of Scene XII, page 26). Although it is based on the Cruikshank illustration The Last Chance, instead of the denizens of Jacob's Island, at their windows, watching the action unfold, in the background the illustrator has placed a church spire and the river, spanned (apparently) by Old London Bridge. Moreover, in the split scene technique, the illustrator has placed constables making to apprehend Toby Crackit within (quite possibly an indication of a cutaway set of Toby Crackit's safe-house used in the 1838 production). As in the Cruikshank illustration, Sikes looks down as, having attached a rope to the chimney, he prepares to descend, but his dog is entirely absent. Since animals are notoriously unreliable on stage, the illustration may very well reflect the fact that the director and playwright decided to dispense with Bull's-eye in this scene.

By the end of 1838, scarcely six weeks after volume publication, Oliver Twist had been staged by six different theatres in London. By 1850, despite the unsavoury nature of the dramatisations and the concomitant adverse reaction by the official censor, the Examiner of Plays, to plays that seemed to encourage juvenile criminality, Bolton records fifty different stagings in Britain and America, most of them by "anon." By 1860, some forty versions had been staged in and around London, including the first printed text, Oliver Twist; or, The parish boy's progress ... adapted from the novel by Mr. Charles Dickens (T. H. Lacy, 1838) by C. Z. Barnett, the other principal adaptations after volume publication being by Thomas Greenwood, Edward Stirling, William Henry Murray, Harwood Cooper, Colin Henry Hazlewood, J. George Moore, and George Dibdin Pitt; however, the standard theatrical text throughout the nineteenth century remained Almar’s, although the latest staging which Bolton ascribes to him is an Anglo-American amalgam curiously entitled Nancy Sikes which ran for about a month at London’s Olympic Theatre from 9 July 1878. "This Play," announced its programme on 19 November 1838, "can be performed without risk of infringing any rights" (Pemberton 11), implying that somehow it enjoyed Dickens's sanction; thus, it came to be published in the Dicks' Standard Drama series as No. 293, and is therefore the most accessible Victorian adaptation of the novel.

References

Ackroyd, Peter. Dickens: A Biography. London: Sinclair-Stevenson, 1990.

Almar, George. Oliver Twist A Serio Comic Burletta in Four Acts. London: John Dicks Standard Drama, c. 1840.

Almar, George. Oliver Twist A Serio Comic Burletta in Three Acts. London: Lacy, c. 1838.

Almar, George. Oliver Twist A Serio Comic Burletta in

Four Acts. New York: Samuel French, 1864. Rpt. Delhi, India, 2015.

Barnett, Charles Zachary. Oliver Twist; or, The parish

boy's progress: A Drama in Three Acts adapted from the novel by Mr Charles

Dickens. London: Thomas Lacey, 1838. Bolton, H. Philip. Dickens Dramatized. Boston:

G. K. Hall, 1987. Fulkerson, Richard P. "Oliver Twist in the

Victorian Theatre." Dickensian 70 (1974): 83-95. Matz, B. W. "Oliver Twist on Stage." Dickensian 1 (1905): 211-212. Maunder, Andrew. "Chapter Five: Sensation Fiction on Stage." The Cambridge Companion to Sensation Fiction, ed. Andrew Mangham.

Cambridge: Cambridge U. P., 2013. Pp. 52-69. Meisel, Martin. "Dickens through a Horse-collar." Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in

Nineteenth-Century England. Princeton U. P., 1983. Pp. 251-265. Morley, Malcolm. "Early Dramas of Oliver

Twist." Dickensian 43 (1947): 74-79. Pemberton, T. Edgar. Charles Dickens and The

Stage. London: George Redway, 1888. Rowell, George. The Victorian Theatre 1792-1913, A

Survey. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1956. Rpt. 1967. Last modified 15 October 2015