Introduction: artist and antiquarian

eorge Heywood Maunoir Sumner (1853–1940) is well known as an Arts and Crafts designer. An associate of William Morris in the 1880s and 90s, he was also a member of the Art Workers’ Guild and the Century Guild. Versatile in the manner of so many of his contemporaries, Sumner produced tapestries (which were made by Morris and Co); mosaics; stained glass windows; paintings; furniture; and architectural decorations. He is perhaps best remembered for his sgraffito panels. These were coloured designs in plaster using an Italian technique and creating an effect which seems both archaic and modern. Good examples can be seen in St Mary’s Church, Sunbury, Surrey, in All Saint’s, Kensington, London , and in the little known church of St Mary the Virgin, Llanfair Kilgeddin, Monmouthshire.

However, these activities were only some of his achievements. Perhaps disillusioned with the practice of Arts and Crafts as a source of employment, Sumner abandoned professional design and in the later part of his career became an antiquarian and historian, publishing books on traditional folk songs and Roman and Neolithic monuments. Tirelessly creative, he switched apparently effortlessly from the demands of fine and applied art to the scholarly investigation of Stonehenge and the prehistoric monuments of Cranborne Chase in the New Forest, close to his home at Cuckoo Hill. He designed this house, its furnishings, and its garden; surrounded by artefacts of his own making, he lived his life in the manner of Morris’s ideal of practicality and beauty.

These varied specialisms have been the subject of scholarly investigation. His ecclesiastical work is essentially well-charted, and so are his archaeological studies. Less attention has been directed at his work as an illustrator and binder. Sumner worked on four books: a version of Cinderella(1896); another juvenile, Jacob and the Raven(1896); and two translations of texts by F.H.K.De La Motte Fouqué. Sintram and His Companions was published in 1883, and this was followed in 1888 by Undine. Both books are fine examples of late Victorian illustration and are embellished with distinctive cloth bindings.

Sumner as illustrator: text and style

r Heywood Sumner shows a charming decorative sense and imaginative feeling’. So writes Walter Crane in his classic account Of the Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New (p.166). Crane’s comments are telling: Sumner’s illustrations are both ornamental and interpretive, helping the reader to understand the text while entertaining his eye.

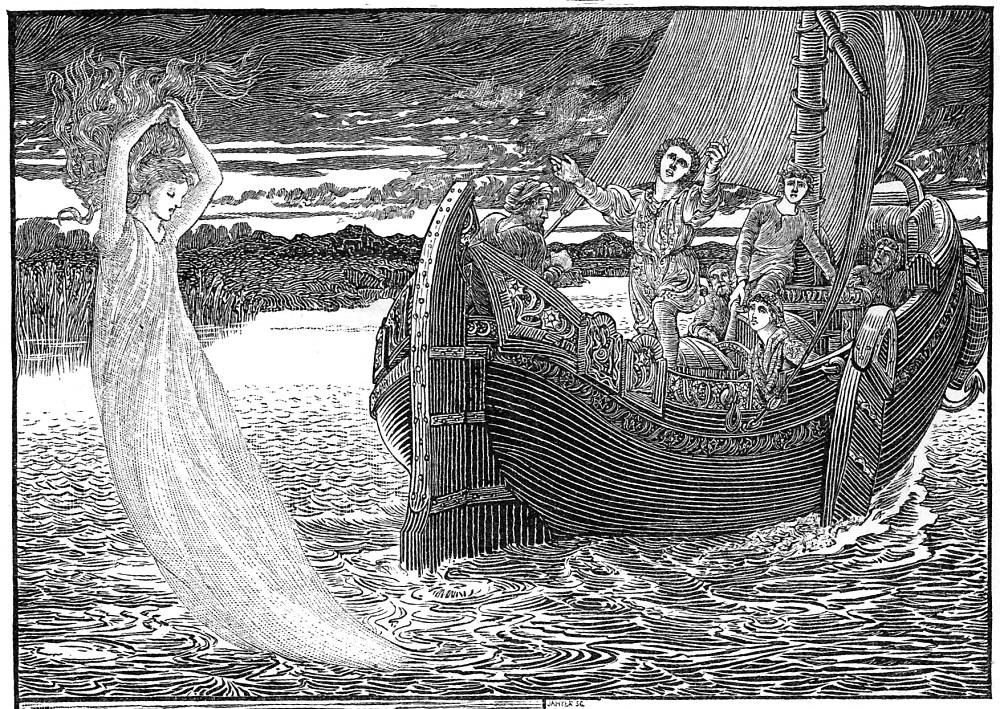

One focus is the representation of tone, and Sumner notably preserves the author’s combination of dramatic narrative and dreamy fantasy, ‘half asleep and half awake’ (Undine,p.105). Some of the illustrations are neo-medieval representations of archaic interiors, costumes and décor, shown in a bright light in which every detail is seen; while the other, hallucinatory elements are depicted an ethereal shadow. Sumner’s sensitive approach is exemplified by the illustration of Undine hovering over the waters of the Danube with Huldrand reaching out to her from the deck of the bark (Undine, p.95): at once real and dream-like, it mediates between the text’s inner tensions. The effect is quaint in the manner of medieval picture-books, and both publications focus on the slippage between myth and history. Yet their prime interest lies in their fusion of a series of styles, and Sumner manipulates a number of sources in the production of his imagery.

Two illustrations from Undine. [Click on these images for larger pictures.]

A central influence is second stage Pre-Raphaelitism, the archaic picture-making which pervaded the Arts and Crafts Movement and the language Sumner deploys throughout his stained glass windows and tapestries. Both books are fine examples of late Pre-Raphaelite design and the lineage from the 1860s to the 1880s is lucidly expressed in Sumner’s flexible manipulation of a well-established code. For example, the medievalist interiors (Undine, pp.72–73; Sintram, pp. 1, 117) recall the detailed rooms of William Holman Hunt and J. E. Millais in their reading of Tennyson’s verse in the famous Moxon edition (1855); the female figures, described by R.E.D. Sketchley as ‘gracefully designed’ (p.7), are versions of Pre-Raphaelite beauty in the manner of Dante Rossetti and Frederick Sandys; and other physical types are clearly modelled on the linear tableaux of Edward Burne-Jones.

At the same time, Sumner’s designs are closely linked to other, contemporary treatments of Pre-Raphaelite style. His illustrations prefigure Arthur Gaskin’s gloss of Pre-Raphaelite imagery in Good King Wenceslas (1894) and also look forward to Bernard Sleigh’s treatments of the nineties. Sumner’s two books can be positioned, in short, as Arts and Crafts versions of Pre-Raphaelite conventions: radical and traditional, they represent a continuity with the earlier part of the movement while suggesting how Pre-Raphaelitism will develop.

Sumner also explores the connection between the rusticity of ‘Germanism’ and the evolving Art Nouveau of the 1880s. Mindful of the fact that both texts were illustrated in the style of Germanic graphic art by H. C. Selous and John Tenniel in the 1840s and '50s, Sumner self-consciously quotes the visual idiom of these artists, and of others, such as John Franklin, who employed Alfred Rethel’s Teutonic rusticity. Sintram’s pictorial frontispiece acknowledges the idea that a German text demands to be visualized in a German style: the swirling arabesque containing a figure is a type of composition that appears in books by Franklin, Selous and Tenniel, linking Sumner’s interpretation with an older tradition. It is also a version of Art Nouveau, a flame-like line that is as much of the eighties and nineties as it is of the forties and fifties. In this way Sumner offers a book for the visually literate viewer of the late nineteenth century, linking his book to several overlapping discourses.

Within this rich synthesis a final ingredient is an elegant celebration of Art Nouveau in the manner of Selwyn Image. Alongside images of Pre-Raphaelite fantasy and Germanic interlaces, Sumner positions a series of decorative headings that enhance the texts with linear friezes of striking modernity. The ‘new style’ is most forcefully conveyed in the patterns appearing on the covers, both of which were designed by the artist; drawn in black line, they bear interesting comparison with the gilt patterns of A. A. Turbayne, and, as in the work of that designer, promote Art Nouveau as a revolutionary style to a large readership.

Works Cited: books designed by Sumner

De La Motte Fouqué, F. K. M. Sintram and his Companions. Illustrated by Heywood Sumner. London: Seeley Jackson & Halliday, 1883.

De La Motte Fouqué, F. K. M. Undine. Illustrated by Heywood Sumner. London: Chapman & Hall, 1888.

Secondary material

Barbour, Jane. ‘Sumner, (George) Heywood Maunoir (1853–1940)’, rev. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online ed. Sept 2012 [http.//www.oxforddnb,com/view/article/38033, accessed 20 Dec 2013].

Crane, Walter. Of the Decorative Illustration of Books Old and New. London: Bell, 1905.

De La Motte Fouqué, F. K. M. Sintram and his Companions.Illustrated by H. C. Selous. London: Lumley [1845].

De La Motte Fouqué, F. K. M. Undine. Illustrated by John Tenniel. London: Lumley [1855].

Morgan-Guy, John. ‘Heywood Sumner’s Masterpiece Restored’. www.imaginingthe bible.org./wales/llanfairkilgeddin.html (accessed 30 December 2013)

Sketchley, R.E.D. English Book Illustration of Today. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trübner & Co., 1901.

Last modified 7 January 2014