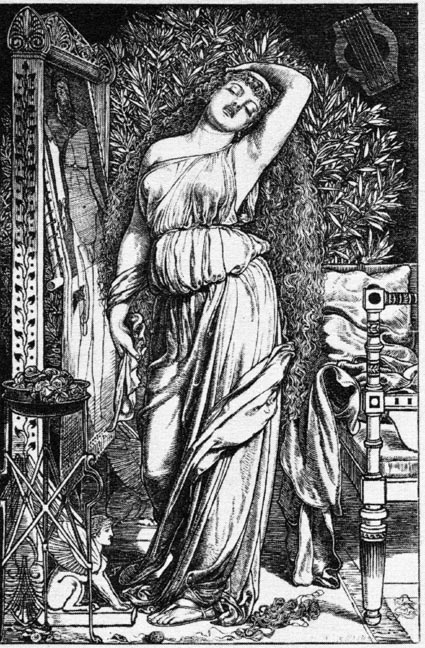

Danaë in the Brazen Chamber

1866

Frederick Sandys

Wood engraving on cream chine-collé paper

7 x 4 5/8 inches (17.8 x 11.6 cm)

Joseph Swain (signed by engraver in plate lower right: Swain, sc.)

Private Collection; reproduced in The Century Guild Hobby Horse, facing p. 147.

Image courtesy of Dennis T. Lanigan. See below for commentary. Mouse over the text for the links.