A Friend of Jack's by Phiz (Hablot K. Browne), seventh serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 4 (October 1857), Chapter 13, facing page 112.

Bibliographical Note

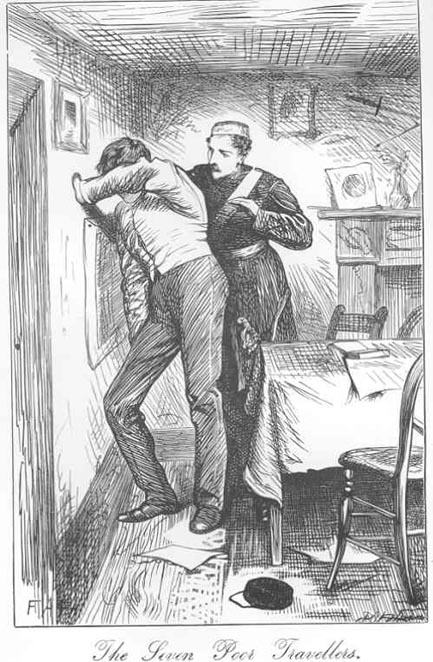

This, the seventh serial illustration for Charles Lever's Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Time, Part 4 (October 1857), Chapter 13, "A Friend of Jack's," is a conventional steel-plate etching; 4 by 5 ⅝ inches (10 cm high by 17.7 cm wide), vignetted. The story was serialised by Chapman and Hall in monthly parts, from July 1857 through April 1859. The ninth and tenth illustrations in the volume initially appeared in reverse order at the very beginning of the fourth monthly instalment, which went on sale on 1 October 1857. This number included Chapters XII through XIV, and ran from page 97 through 128.

Scanned image by Simon Cooke; colour correction, sizing, caption, and commentary by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose, as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image, and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.] Click on the image to enlarge it.

Pssage Illustrated: Jack Kellett writes his father from Sevastopol

“Captain Kellett lives here, doesn't he?” said a tall young fellow, in the dress of a soldier in the Rifles.

Kellett's heart sank heavily within him as he muttered a faint “Yes.”

“I'm the bearer of a letter for him,” said the soldier, “from his son.”

“From Jack!” burst out Kellett, unable to restrain himself. “How is he? Is he well?”

“He's all right now; he was invalided after that explosion in the trenches, but he's all right again. We all suffered more or less on that night;” and his eyes turned half inadvertently towards one side, where Kellett now saw that an empty coat-sleeve was hanging.

“It was there you left your arm, then, poor fellow,” said Kellett, taking him kindly by the hand. “Come in and sit down; I'm Captain Kellett. A fellow-soldier of Jack's, Bella,” said Kellett, as he introduced him to his daughter; and the young man bowed with all the ease of perfect good-breeding.

“You left my brother well, I hope?” said Bella, whose womanly tact saw at once that she was addressing her equal.

“So well that he must be back to his duty ere this. This letter is from him; but as he had not many minutes to write, he made me promise to come and tell you myself all about him. Not that I needed his telling me, for I owe my life to your son, Captain Kellett; he carried me in on his back under the sweeping fire of a Russian battery; two rifle bullets pierced his chako as he was doing it; he must have been riddled with shot if the Russians had not stopped their fire.”

“Stopped their fire!”

“That they did, and cheered him heartily. How could they help it! he was the only man on that rude glacis, torn and gullied with shot and shell.” [Chapter XIII, "A Message from Jack," page 112]

Note: The "chako" or "shako" was a tall, cylindrical piece of military headgear, usually with a visor, and sometimes tapered at the top. Specimens from the period are adorned with some kind of ornamental plate or badge on the front, metallic or otherwise, and often will have a feather, plume, or pompom attached at the top — see the Furniss illustration below. Other spellings include "czako," "schako," and "tschako."

Commentary: A Letter from the Crimean Theatre of War

Readers of the novel in the Chapman and Hall monthly parts might have felt that they were receiving a "real-time" text rather than an historical reminiscence; in fact, Lever seems to have set the action in just the previous year, so that, for example, the Crimean War still rages beyond the shabby confines of Dublin (the setting of this seventh monthly illustration) and the elegant Villa d'Este at Lake Como in Italy. Since the war effectively ended with the Czar's acquiescing to Austrian peace terms in January 1856, the date of the present action, when retired army Captain Paul Kellett receives a letter from his son, Jack, stationed in the Crimea, is either late autumn, 1855, or possibly 1854. Lever makes no allusions to figures such as Florence Nightingale (who arrived in the war zone in October 1854) or incidents such as the Charge of the Light Brigade (25 October 1854) which might help the reader in establishing this chapter's chronological setting. Lever's discussion of the new divorce provisions considered by Parliament complicates further a satisfactory dating of the action since the Commons was actively debating that legislative initiative in 1856 — and Lady Grace, Lady Lackington, and Davenport Dunn in the Chapter 10, "A 'Small Dinner'," seem to be discussing the divorce courts as if they were already in operation. A telling detail added by Charles Conway, the young soldier who delivers the letter to Kelletts, is that members of his corps are now using the Minie rifle, an allusion which dates the action to 1854; it was replaced by the Enfield rifle in April 1855.

Like Phiz's other illustrations, this one provides a guide that makes clear which set of characters Lever follows in a particular chapter. Here, the novelist transports serial readers from the affluent environment of the Villa d'Este to the shabby environs of the Dublin suburb where Paul Kellett and his daughter live. In telling Jack Kellett's inset story, Lever makes use of conventional narrative, the first-person account of the young Welsh private, an epistolary document, and Phiz's illustration, from which the reader may immediately see that the young man in uniform has lost an arm, and is therefore in all likelihood a Crimean veteran. Until the readers complete the chapter by perusing the letter that Private Charles Conway has delivered, they cannot be sure whether Jack Kellett has survived the initial battles of the Crimean campaign.

Bella and her father recognise their visitor as a member of "the Rifles" because, as most British readers of 1857 would have known, the two regiments of sharp-shooters (the King's Royal Rifle Corps and the Rifle Brigade) did not wear the conventional red uniforms of the British military, but rather dark green (almost black) uniforms. In Ireland in particular interest in the war was running high by 1856, and Irish soldiers had served with distinction in the Crimea:

In Ireland there was much public interest in both the regiments and the men and women departing for the Crimea. This was due to the great number of Irishmen recruited in Ireland and serving in the British army. Irish-born soldiers serving in 1854 constituted some 30–35 per cent of the army, and it is estimated that by the end of the war, around 30,000 Irish soldiers had served in the Crimea. It was a sailor, Charles Lucas, an Irishman from Poyntzpass, County Armagh, who won the very first Victoria Cross; it was awarded for his gallantry during a Royal Navy action against the Russians in the Baltic in 1854. In total, 28 men of Irish birth were awarded the Victoria Cross during the Crimean War. ["Event: Sunday, 17 December, 1854."]

Lever has made Private Jack Kellett a member of the most distinguished corps in the British forces serving in the Crimea. Known simply as "The Rifle Brigade" from the period in which British forces defeated Napoleon, from the outbreak of hostilities in 1853 the Rifle Brigade sent two battalions which saw fierce action at the Alma River, across which one of the battalions led the advance, at Inkerman, and at the Siege of Sevastopol. Lever, writing in 1857, would have been aware (as would many of his readers) that the regiment won eight Victoria Crosses during the Crimean War, more than any other regiment.

Jack Kellett's Letter from the trenches at Sevastapol

“How joyously he writes!” continued Bella, as she bent over the letter: “'I see by the papers, dearest Bella, that we are all disgusted and dispirited out here, — that we have nothing but grievances about green coffee and raw pork, and the rest of it; don't believe a word of it. We do curse the Commissariat now and then. It smacks like epicurism to abuse the rations; but ask Charley if these things are ever thought of after we rise from dinner and take a peep at those grim old earthworks, that somehow seem growing every day, or if we grumble about fresh vegetables as we are told off for a covering party. There's plenty of fighting; and if any man hasn't enough in the regular way, he can steal out of a clear night and have a pop at the Russians from a rifle-pit. I'm twice as quick a shot as I was when I left home, and I confess the sport has double the excitement of my rambles after grouse over Mahers Mountain. It puts us on our mettle, too, to see our old enemies the French taking the work with us; not but they have given us the lion's share of it, and left our small army to do the same duties as their large one. One of the regiments in our brigade, rather than flinch from their share, returned themselves twelve hundred strong, while they had close upon three hundred sick, — ay, and did the work too. Ask dad if his Peninsulars beat that? Plenty of hardships, plenty of roughing, and plenty of hard knocks there are, but it's the jolliest life ever a fellow led, for all that. Every day has its own story of some dashing bit of bravery, that sets us all wild with excitement, while we wonder to ourselves what do you all think of us in England. Here comes an order to summon all to close their letters, and so I shut up, with my fondest affection to the dear old dad and yourself.

“'Ever yours,

“'Jack Kellett.

“'As I don't suppose you'll see it in the “Gazette,” I may as well say that I'm to be made a corporal on my return to duty. It's a long way yet to major-general, but at least I'm on the road, Bella.'” [126

Significant historical background: The Crimean War (1854-56)

- The Great Storm: 14 November 1854

- Alma Crimea 1854

- The New York Times' account of the Battle of Inkerman

- The British landing at Eupatoria

- Voice from the Ranks: Sevastopol — the First Assault

- The Crimean War: "Britain in Blunderland"

- The Crimean War: Visual Materials

Relevant images of Crimean War era uniforms, 1861-1911

Left: John Bell's statue group The Brigade of Guards from Crimean War Memorial (1861), located in Waterloo Place, at the junction of Lower Regent Street and Pall Mall, London. Centre: Harry Furniss's lithograph of the Dickens Christmas Story about the Crimean War, "The Tale of Richard Doubledick" in The Seven Poor Travellers, The Death of Major Taunton (1910), illustrating a framed tale which originally appeared in the Christmas 1854 number of Household Words. Right: The F. A. Fraser illustration of the same story, showing the everyday uniforms of the period, "The Seven Poor Travellers" (1911). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Other Illustrations involving the Crimean War background of the story

- Frontispiece, Attorney Reggis captured by Cossacks behind Russian lines (April 1859)

- The Pony Race (October 1857)

- Catching a Colonel (September 1858)

- Charley the Smasher (February 1859)

- The Vision (March 1859)

References

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: A Man of Our Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, 1859.

Lever, Charles. Davenport Dunn: The Man of The Day. Illustrated by "Phiz" (Hablot Knight Browne). London: Chapman and Hall, October 1857 (Part IV).

Northern Ireland War Memorial Home Front Exhibition. "Event: Sunday, 17 December, 1854." Royal Irish: The Irish Soldier in Service to the Crown. 2019.

Last modified 28 August 2019