In this posture we marched out

Wal Paget (1863-1935)

half-page lithograph

10 cm high by 6.5 cm wide, vignetted.

1891

Robinson Crusoe, embedded on page 168; signed "Wal Paget" lower right.

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham.

[You may use these images without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the photographer and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the VictorianWeb in a print one.]

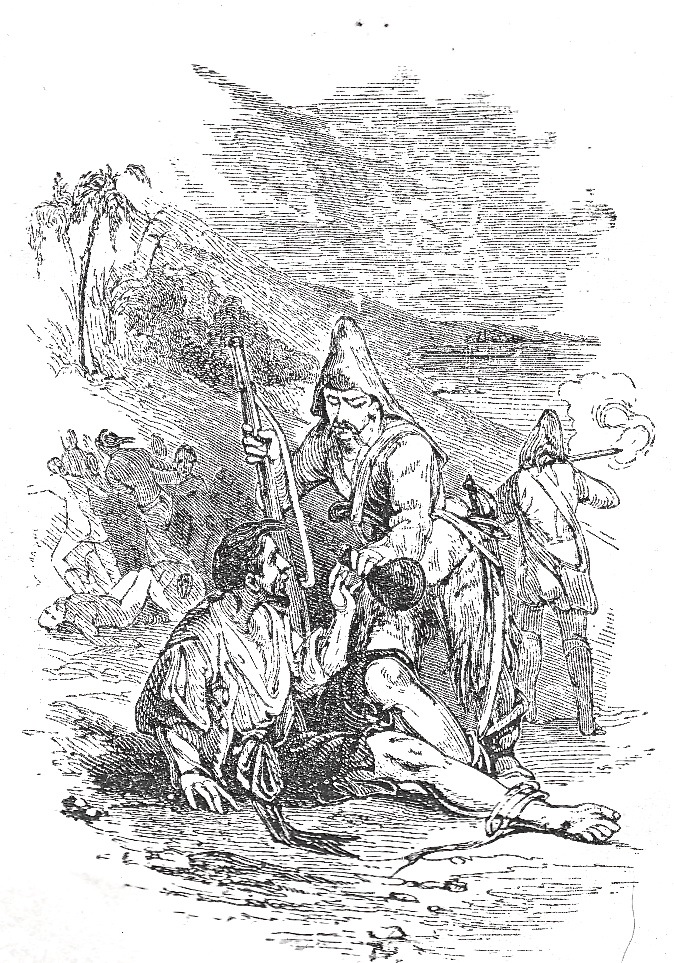

Passage Illustrated: Crusoe arms Friday in preparation for meeting the Cannibals

In this fit of fury I divided the arms which I had charged, as before, between us; I gave Friday one pistol to stick in his girdle, and three guns upon his shoulder, and I took one pistol and the other three guns myself; and in this posture we marched out. I took a small bottle of rum in my pocket, and gave Friday a large bag with more powder and bullets; and as to orders, I charged him to keep close behind me, and not to stir, or shoot, or do anything till I bid him, and in the meantime not to speak a word. In this posture I fetched a compass to my right hand of near a mile, as well to get over the creek as to get into the wood, so that I could come within shot of them before I should be discovered, which I had seen by my glass it was easy to do. [Chapter XVI, "Rescue of the Prisoners from the Cannibals," page 166]

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Commentary: To intervene or not

Paget focuses exclusively on Crusoe and Friday as they prepare to monitor and perhaps intervene in the activities of the cannibals. Crusoe initially vacilates between shooting the detested "naked, unarmed wretches" (106) and remaining aloof, and therefore undetected. However, as the reader turns the page to encounter the complementary illustrations, it becomes obvious that something has prompted Crusoe to intervene after all. Crusoe's expression of indignation is such that the reader wonders whether he will maintain his determination not to intervene. In contrast to the Cannibals Dancing in the Cruikshank sequence, Paget does not show the celebrants preparing for a communal meal; rather, ten of the cannibals have already fallen as Friday and Crusoe discharge their muskets from the trees bordering the beach. Whereas Cruikshank had included, too, the bonfire and canoes in the background and foregrounded Crusoe and Friday, Paget focuses on the heavily armed Crusoe and his companion (left) and the eighteen natives, right. Whereas Phiz had recorded the violent assault on the natives, Cruikshank and Paget momentarily leave the reader wondering about the outcome of the ensuing action. Although Paget seems to give Crusoe the twin advantages of cover and surprise, the action is not over yet. To the left, Paget isolates the heavily armed figures of Crusoe and Friday, now dressed similarly as if to represent the forces of civilisation which oppose the barbarous practices of the natives. However, Paget is not without sympathy for the natives, who are unarmed and confused as to how they are being attacked — and are, moreover, not engaged in preparing to butcher their captives, who are not in evidence. Although Defoe insists the cannibals are naked, Paget has elected (perhaps out if a sense of Victorian propriety) to clothe them in loin-cloths at least whenever he includes them in the frame. Here, Crusoe and his man-servant (rather more like an adopted son) appear on the left-hand page, and the cannibals, under attack by the concealed Crusoe and Friday, on the right-hand page, so that one reads Paget's illustrations as both sequential and complementary. Already in the text accompanying the former illustration Crusoe and Friday have discharged several pieces and are stepping forward to decrease the distance between themselves and their targets. They are letting fly "in the name of God!" (168) because they are coming to the rescue of a "poor Christian" (167), a bearded European who is about to be butchered.

Related Material

- Daniel Defoe

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe il. H. M. Brock at Project Gutenberg

- The Further Adventures of Robinson Crusoe at Project Gutenberg

Relevant illustrations from other 19th editions, 1790-1867

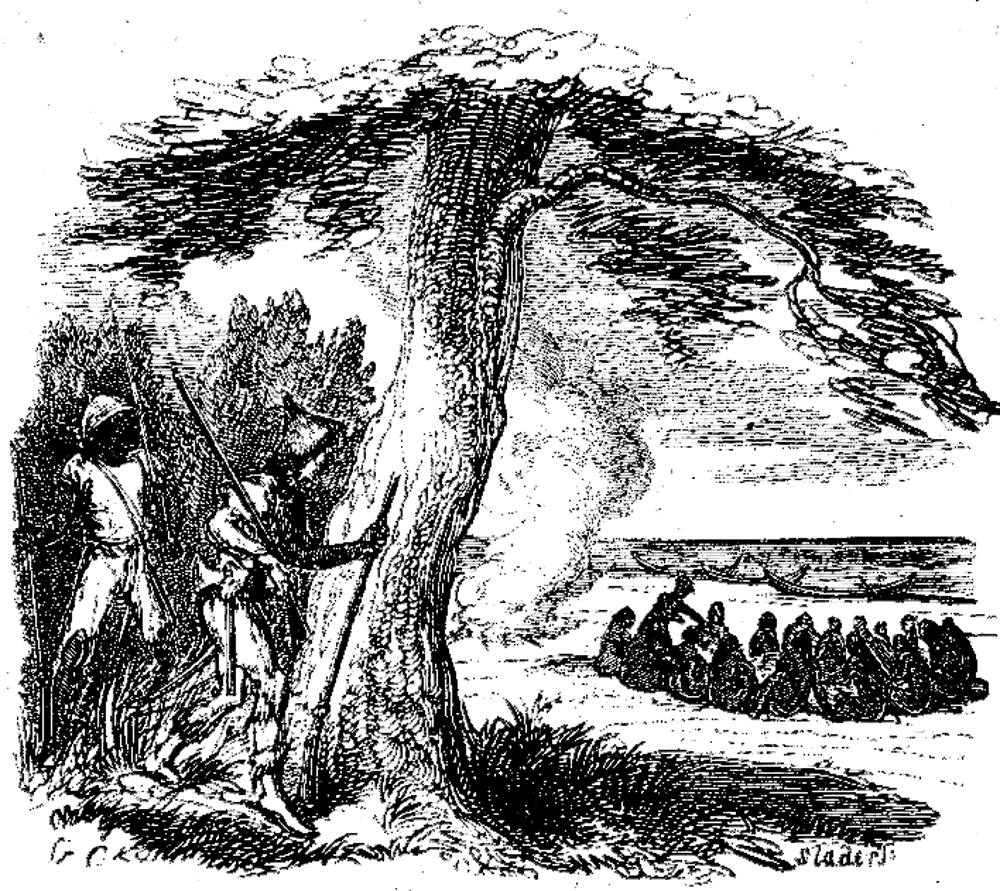

Above: Cruikshank's somewhat theatrical scene of Crusoe and Friday's spying upon the cannibals, Crusoe and Friday watch the Cannibals from hiding (1831). [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

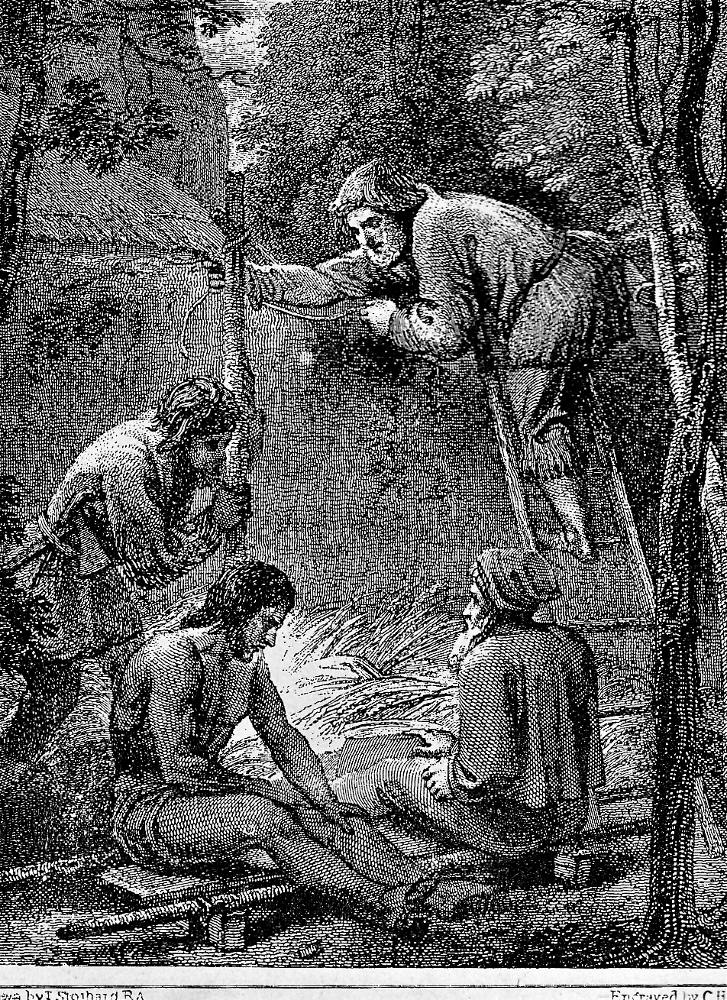

Above: Phiz's's dramatic steel-engraving of Crusoe's rescuing the cannibal's European captive, Robinson Crusoe rescues the Spaniard (1864).

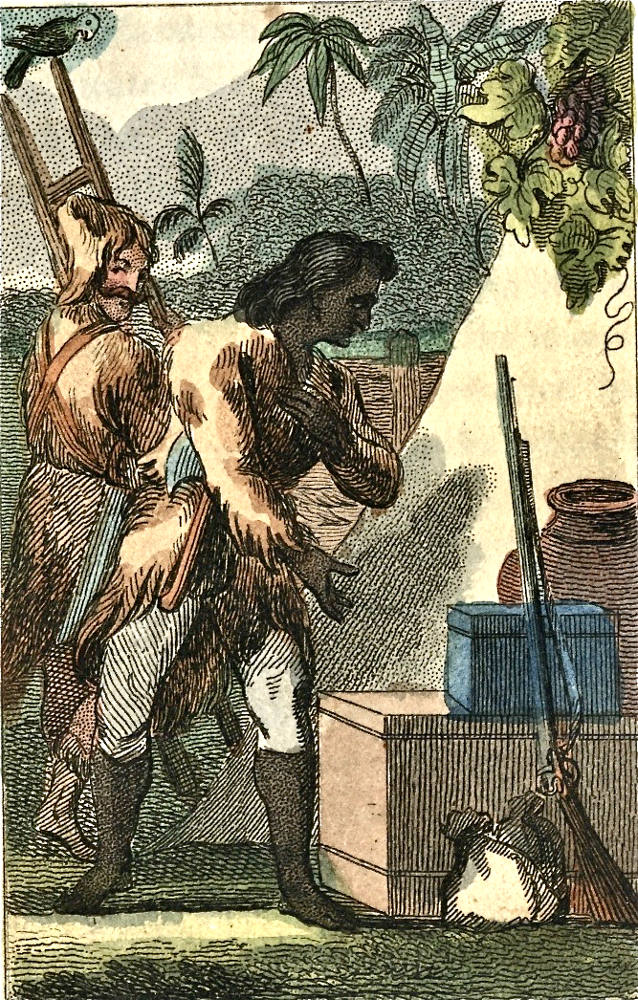

Left: The original Stothard copper-plate engraving in which Crusoe welcomes both former captives, the Spaniard and Friday's father (1790), Robinson Crusoe builds a tent for Friday's father and the Spaniard. Centre: From the 1818 children's book, the far less violent Friday and his Father. Right: John Gilbert's realisation of the rescue scene, de-emphasizing the violence and bloodshed, The Rescue of the Spaniard (1860s).

Reference

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe Of York, Mariner. As Related by Himself. With upwards of One Hundred and Twenty Original Illustrations by Walter Paget. London, Paris, and Melbourne: Cassell, 1891.

Victorian

Web

Visual

Arts

Illustra-

tion

Walter

Paget

Next

Last modified 4 May 2018