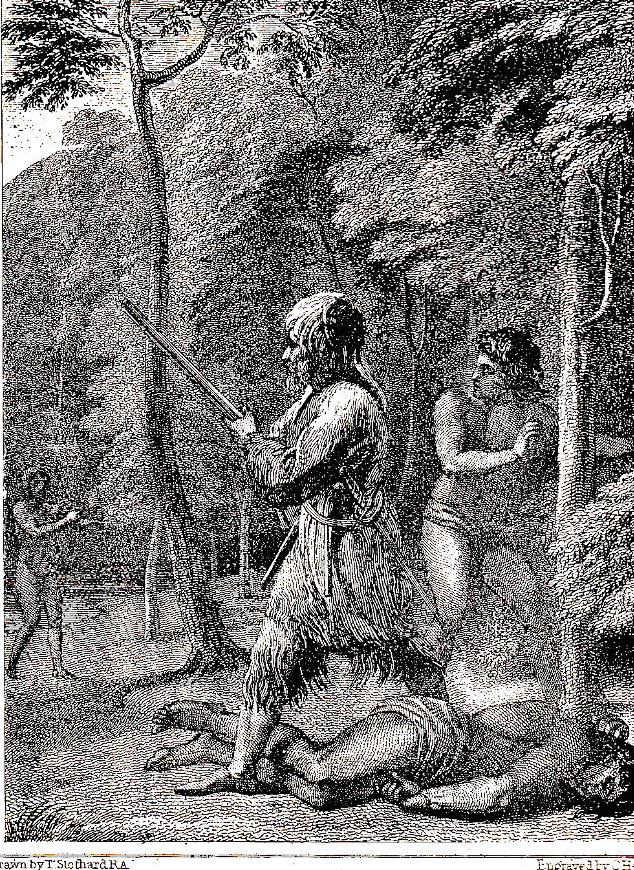

Cannibals dancing around a fire by George Cruikshank as the title-page vignette for the John Major edition of The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (1831). In 1830 publisher Thomas Roscoe had recruited Cruikshank to do a series of Crusoe illustrations for his Novelist's Library in competition with publisher John Murray's Family Library. However, as Robert L. Patten notes, that project fell through just as Major asked Cruikshank to undertake an identical commission. Vignette: 3.7 cm high by 6.5 wide. [Click on the image to enlarge it.]

Scanned image and text by Philip V. Allingham. [You may use this image without prior permission for any scholarly or educational purpose as long as you (1) credit the person who scanned the image and (2) link your document to this URL in a web document or cite the Victorian Web in a print one.]

Passage Anticipated: The Unwelcome Visitors to Crusoe's Island

When I was come down the hill to the end of the island, where, indeed, I had never been before, I was presently convinced that the seeing the print of a man's foot was not such a strange thing in the island as I imagined: and but that it was a special providence that I was cast upon the side of the island where the savages never came, I should easily have known that nothing was more frequent than for the canoes from the main, when they happened to be a little too far out at sea, to shoot over to that side of the island for harbour: likewise, as they often met and fought in their canoes, the victors, having taken any prisoners, would bring them over to this shore, where, according to their dreadful customs, being all cannibals, they would kill and eat them; of which hereafter.

When I was come down the hill to the shore, as I said above, being the SW. point of the island, I was perfectly confounded and amazed; nor is it possible for me to express the horror of my mind at seeing the shore spread with skulls, hands, feet, and other bones of human bodies; and particularly I observed a place where there had been a fire made, and a circle dug in the earth, like a cockpit, where I supposed the savage wretches had sat down to their human feastings upon the bodies of their fellow-creatures. [Chapter XII, "A Cave Retreat," p. 156]

Commentary

[1831]. The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe . . . illustrated with numerous engravings from drawings by George Cruikshank. London: John Major. Engraving by John Jackson, Thomas Williams, Samuel Williams, Mary Ann Williams and Samuel Machlin Slader. . . . in Major's edition the plates are interspersed throughout the text. . . . Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe were often reused in later editions; the exact provenance of these plates is unclear. [PACSCL Finding Aids]

The title-page vignette heightens readers' expectations over 190 pages as to how the protagonist will overcome the cannibals, whose superior numbers (at least thirty, distributed among five canoes) and knowledge of the place should prove distinct advantages in attacking a single colonist, albeit one armed with muskets. The illustrator's choice of subject for the keynote of his series, title-page vignette, is complicated by the fact that it refers to two different places in the book, and, unlike the other vignettes, is not surrounded by informing text. The first possible source text is that in Chapter XII, "A Cave Retreat," in which Crusoe merely reconstructs or imagines the natives dancing after the feast. The second occurs another thirty-four pages later, when the cannibals return — and Friday, one of th captives, makes a dash for freedom.

The cannibalism that runs as a negative strain throughout the first book of Crusoe’s adventures is not merely the "serpent in Eden," so to speak, but a justification for the European eradication of native religious and cultural traditions and the wholesale takeover of aboriginal territories. The cannibalism, upon which Victorian illustrators such as Cruikshank place considerable emphasis (as in his title-page vignette, "Cannibals Dancing"), then justifies European/Christian violence toward the pagan "other," which has included West Indian and eighteenth-century American colonial slavery:

The confounding irony which reveals a serious identity between Crusoe and the cannibals, however, and accounts for the split the fable effects between them, and for his strong antagonism to them, is that Crusoe set out on the adventure that cast him upon the island for twenty-eight years in order to be a trafficker in Negro slaves. The savagery of this act of consuming and devouring, in order to be denied for the sake of the European conscience, was displaced onto the blacks themselves by inventing a fable that focuses on the more blatant savagery of a simpler cannibalism attributed to them. In Robinson Crusoe, the intended victims become the victimizers, and the original victimizers, the Europeans, can feel righteous and justified in their course of "enterprize." Through its fable, Robinson Crusoe shows the justifying fantasy of the Europeans for their brutal consumption of human lives. [Heims, p. 193]

Crusoe originally has no intention to interfere in the cannibals' second grisly feast as long as they leave him alone. However, when Crusoe realizes that one of the victims is bearded, he concludes that he must intervene to preserve the life of a "Christian," even though such intervention may expose him to considerable danger, both in the actual battle to liberate the Spanish captive, in which he and Friday are badly outnumbered, and afterwards, should any of the cannibals escape to return later to take revenge on Crusoe. In the second half, the Asiatic pagans, the Tartars, receive far gentler treatment from Crusoe and his party because, although their idolatry is anathema to the Christian travellers, it does not represent the utter annihilation of the individual involved in cannibals' rites, which seem to be a perversion or parody of the Christian eucharist.

Bibliographical Note

The "thirty-seven illustrations" announced on the 1890 title-page do not take into account the repetition of the title-page vignette in Cannibals dancing around a fire on the beach in Chapter XIV, "A Dream Realised," page 190. Moreover, the 1890 single-volume re-printing of the 1831 John Major edition does not include either of the original frontispieces of Crusoe, Friday, Will Atkins and Will's wife, placing the emphasis in the re-print firmly on the initial volume of Caribbean adventures.

Related Material

- Illustrations of Robinson Crusoe by various artists

- Illustrations of children’s editions

- Daniel Defoe

- Title-page with vignette

- Frontispiece for the 1831 Edition — Volume One: Robinson Crusoe's first interview with Friday (Vol. I)

- Frontispiece for the 1831 Edition — Volume Two: Will Atkins and his native Wife

Related Scenes from Stothard (1790), Phiz (1864), the 1818 Children's Book, Cassell's (1863-64) and Paget (1891)

Left: Stothard's 1790 realisation of the rescue scene, an illustration of which Cruikshank was probably aware, Robinson Crusoe first sees and rescues his man Friday (copper-plate engraving, [Chapter XIV, "A Dream Realised"). Centre: Phiz's steel-engraved frontispiece, with the surviving pursuer about to attack the unwitting Crusoe, Robinson Crusoe rescues Friday (1864). Right: Colourful realisation of the same scene, with a decidedly subservient and Negroid Friday: Friday's first interview with Robinson Crusoe. (1818). [Click on the images to enlarge them.]

Left: Cruikshank's 1831 realisation of the rescue scene, Crusoe having just rescued Friday (frontispiece, Volume I). Centre: Sir John Gilbert's realisation of the rescue scene, Crusoe rescues Friday (1867?). Right: Realistic but emotionally muted realisation of the same scene, Crusoe and Friday (1863-64).

Above: Wal Paget's realistic interpretation of the cannibals prior to Crusoe's intervening on Friday's behalf, Dancing round the fire (1891).

Bibliography

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, with introductory verses by Bernard Barton, and illustrated with numerous engravings from drawings by George Cruikshank expressly designed for this edition. 2 vols. London: Printed at the Shakespeare Press, by W. Nichol, for John Major, Fleet Street, 1831.

De Foe, Daniel. The Life and Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, Written by Himself. Illustrated by Gilbert, Cruikshank, and Brown. London: Darton and Hodge, 1867?].

Defoe, Daniel. The Life and Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe of York, Mariner. (1831). Illustrated by George Cruikshank. Major's Edition. London: Chatto & Windus, 1890.

Heims, Neil. "Robinson Crusoe and the Fear of Being Eaten." Colby Library Quarterly 19, 4 (December 1983). Pp.190-193. https://digitalcommons.colby.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?referer=https://search.yahoo.com/&httpsredir=1&article=2528&context=cq

Patten, Robert L. "Phase 2: "'The Finest Things, Next to Rembrandt's,' 1720–1835." Chapter 20, "Thumbnail Designs." George Cruikshank's Life, Times, and Art, vol. 1: 1792-1835. Rutgers, NJ: Rutgers U. P., 1992; London: The Lutterworth Press, 1992. Pp. 325-339.

Last modified 3 May 2018