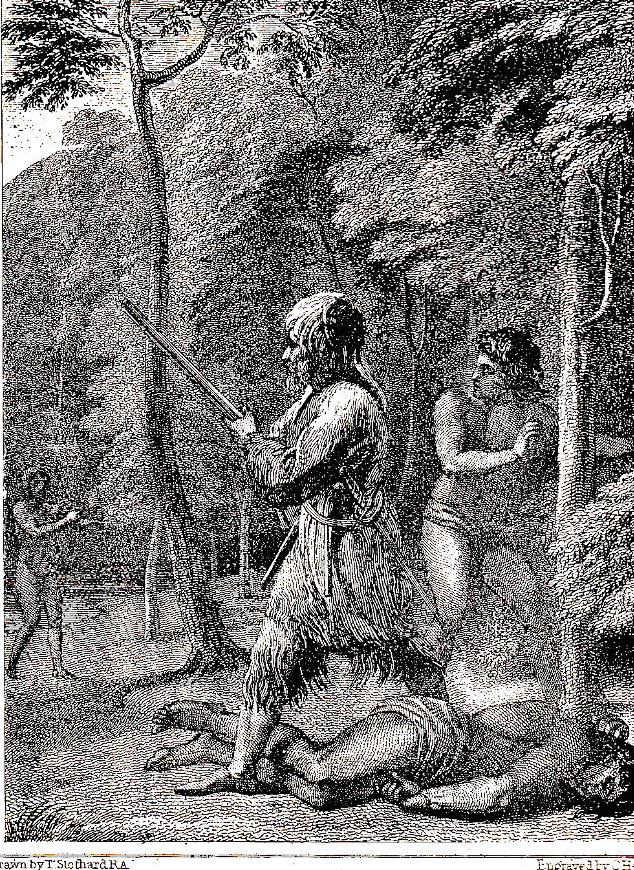

Picture source: Defoe's The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe (London: Harrison, 1782), illustrated by Thomas Stothard.

Biographical Materials: Introduction

When he wrote the first part of The Life and Strange Surprising Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, of York, Mariner, by far the best known of the 375 works with which he is authoritatively credited, Defoe was fifty-nine. By any standard he was one of the most remarkable men who ever lived. Yet while it would be absurd to maintain that his genius has not received its due, one does notice quite commonly in his critics a certain meanness of spirit towards him; praise tends to be grudging; and one can only see in this then vestigial remains of the contempt, which is one of class, expressed in Swift's reference to him as 'the fellow that was pilloried, I have forgot his name'. In fact, Defoe was almost the prototype of a kind of Englishman increasingly prominent during the eighteenth century and reaching its apotheosis in the nineteenth: the man from the lower classes, whose bias was essentially practical and whose success in life, whether in trade or industry, was intimately connected with his Protestant religious beliefs and the notion of personal responsibility they inculcated. — Walter Allen, The English Novel, pp. 37-38.

Early Life

Born Daniel Foe, probably in the parish of St. Giles Cripplegate, London, Daniel Defoe in youth seemed destined for a career as a dissenting minister. Neither the date nor the place of his birth are documented. His father, James Foe, although a member of the Butchers' Company, was a hard-working London tallow chandler, and a devout Presbyterian. Daniel later changed his name to “Defoe,” out of a desire to have it sound more gentlemanly. Occasionally, he would claim descent from the family of De Beau Faux. Defoe graduated from Reverend Charles Morton’s academy for the children of dissenters at Newington Green—Morton later emigrated to Massachusetts and became vice-president of Harvard University.

In 1683, in his early twenties, Defoe went into business, abandoning his original intention to become a Non-conformist minister. As a businessman he traveled widely, trading principally in hosiery, general woollen goods, and wine. To fulfill his lofty ambitions, he purchased a country estate, a trading vessel, and civet cats with which to make perfume. In 1692, Defoe was arrested for non-payment of a £700 debt, although his liabilities may have amounted to £17,000. Following his release, he probably travelled in Europe and Scotland, and probably traded in wine to Cadiz, Porto, and Lisbon. By 1695 he was back in England, using the name "Defoe", and serving as a "commissioner of the glass duty," a minor official responsible for collecting the tax on bottles. Pursuing a lifelong interest in politics, Defoe published a political pamphlet in 1683, his first literary piece. In 1696, he was operating a tile and brick factory in Tilbury, Essex. Recognizing that he would never repay all his debts if he stayed in business, in 1703 Defoe gave up business entirely for writing.

Engagement in Political and Religious Issues

As a staunch Protestant, Defoe joined the disastrous rebellion by the son of Charles II, the Duke of Monmouth, when James II, a Roman Catholic, ascended the British throne on 2 February 1685. Luckily, Defoe escaped the ill-fated Battle of Sedgemoor, Somerset, on 6 July 1685, in which the rebels were routed. Three years later, Defoe sided with William of Orange against the Jacobites, the supporters of King James II, who went into exile after the Glorious Revolution of 1688. One of his most popular works during the reign of Queen Mary and William III was The True-Born Englishman (1701), in which he defended the Dutch Protestant monarch against racial prejudice, calling him "William, the Glorious, Great, and Good, and Kind." Throughout William III's reign, Defoe supported him loyally as his leading pamphleteer.

In 1702, as a result of suppression of religious dissent by the established Church of England, Defoe adopted a rhetorical strategy which Jonathan Swift, championing the cause of Ireland, would emulate in A Modest Proposal For Preventing the Children of Poor People From Being a Burden to Their Parents or Country, and For Making Them Beneficial to the Public (1729). In The Shortest Way with the Dissenters, Defoe writing anonymously appears to embrace the religious intolerance of some radical Anglicans in order to reduce their position to absurdity. Although he sided with the Dissenters, Defoe pretended to advocate for the "off-with-their-heads" stance towards any who dared to diverge from the tenets of the Church of England. The authorities at first thought the anonymous author of the pamphlet was in earnest, and many unwary Church authorities embraced the political agenda of the seemingly rabid document. When his authorship and true intention were discovered, he was arrested for sedition, and on 31 July 1703 Defoe was sentenced to both a prison term and three successive appearances in the public pillory, a penalty usually reserved for those guilty of public immorality. However, he turned his punishment into a triumph when his supporters sang a satirical song that Defoe had composed especially for his public humiliation ("Hymn to the Pillory," 1703) and pelted him with flowers rather than with the customary rotting fruits and vegetables at him. After his three days in the pillory, Defoe was sent to Newgate Prison. In exchange for Defoe's agreeing to serve as a government spy, Robert Harley, First Earl of Oxford, arranged the pamphleteer's release. Subsequently, masquerading as a merchant (although he was in truth a government operative), Defoe travelled throughout western Europe and Scotland, trading in wine from Cadiz, Porto, and Lisbon. By 1695 he was back in England, using the name "Defoe," and serving as a "commissioner of the glass duty," collecting the tax on bottles. He mined his mercantile travels from these years in the three-volume Tour Through the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724–26).

Defoe was absorbed by English foreign policy since he feared that, as a consequence of the Treaty of Rijswijk (1697), Great Britain would become embroiled in a major European war which the death of the childless Spanish king would precipitate—hence its name, The War of Spanish Succession (also called Queen Anne's War). To support his political masters, in 1704 Defoe established the pro-Tory political periodical A Review of the Affairs of France, which ran uninterrupted for the next nine years. When Harley lost power in 1708, Defoe continued writing it to support Godolphin, then again to support Harley and the Tories in the Tory ministry of 1710 to 1714. After the death of Queen Anne and the Tories’ fall from power, Defoe continued his intelligence work for the Whig government, meanwhile continuing as a political writer and journalist, activities which occasionally landed him in jail. Just after the accession of King George I in 1714, perhaps prompted by a severe illness, Defoe wrote the best known and most popular of his many educational works, The Family Instructor.

Takes up a Writing Career

Suddenly turning his back on party factionalism in 1719, Defoe, aged 59, published companion Robinson Crusoe novels, true-to-life fictions based on several short essays that he had composed over the years and mining the castaway experiences of sailor Alexander Selkirk and of Henry Pitman, a castaway who had been surgeon to the Duke of Monmouth. Another five novels followed between 1722 and 1724, for the most part employing rogues and criminals as the protagonists: Moll Flanders, Colonel Jack, Captain Singleton, The Journal of the Plague Year, and Roxana.

In the mid-1720s, Defoe returned to writing editorial pieces, focusing on such subjects as morality, politics and the breakdown of social order in England. Some of his later works include Everybody's Business is Nobody's Business (1725); the nonfiction essay "Conjugal Lewdness: or, Matrimonial Whoredom" (1727); and a follow-up piece to the "Conjugal Lewdness" essay, entitled "A Treatise Concerning the Use and Abuse of the Marriage Bed."

Final Years: Death in Poverty

Although hardly working in optimal conditions for a writer, Defoe continued producing pamphlets and manualswell into 1728, when he was in his late sixties, but he was never able to avoid his debtors, including a Mary Brooke. To escape these harassing creditors Defoe lodged in a rooming-house in the Barbican area of central London, in Ropemaker's Alley. Defoe's last years had been fraught with legal problems resulting (allegedly) from unpaid bonds dating back a generation, and he probably he died while in hiding, on 24 April 1731. Given his later national and international popularity as a writer, it is ironic that he was buried in Bunhill Fields under the name "Dubow" because a semi-literate gravedigger has misspelled the name he was given at the boarding house. Although his novels continued to be best-sellers in the next century, Defoe was stalked in his final years, as Moll Flanders says, by the "spectre of poverty" The cause of his death was labelled as lethargy, suggesting that he probably experienced a stroke. He was interred two days later in in what is today Bunhill Fields Burial and Gardens alongside such Puritan worthies as John Bunyan, in the Borough of Islington, London, where a subscription list of seventeen hundred persons (undoubtedly admiring readers) with a Christian newspaper resulted in the erection of a plain stele to his memory in September 1870.His chief contribution to European letters is the distinction of having written the ultimate boys' adventure book:

As De Foe was a man of very powerful but very limited imagination — able to see certain aspects of things with extraordinary distinctness, but little able to rise above them — even his greatest book shows his weakness, and scarcely satisfies a grown-up man with a taste for high art. In revenge, it ought, according to Rousseau, to be for a time the whole library of a boy, chiefly, it seems, to teach him that the stock of an iron-monger is better than that that of a jeweller. We may agree in the conclusion without caring about the reason; and to have pleased all the boys in Europe for near a hundred and fifty years is, after all, a remarkable feat. [Leslie Stephen, "De Foe's Novels"]

Victorian Afterlife

Defoe's Robinson Crusoe cotinued to be enormously popular in the nineteenh century, and was frequently abridged and adapted for younger readers. A number of prominent Victorian artists, including the Dickens illustrators George Cruikshank, Hablot Knight Browne (Phiz), and Wal Paget published illustrated editions that emphasized the exotic and adventure-story aspects of the novel The Adventures of Robinson Crusoe and its sequel, The Farther Adventures of Robinson Crusoe, often issued together in a single volume.

The children's pantomime Robinson Crusoe was staged at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, in 1796, with Joseph Grimaldi as Pierrot in the harlequinade. The piece was produced again in 1798, this time starring Grimaldi as Clown. In 1815, Grimaldi played Friday in another version of Robinson Crusoe.

Jacques Offenbach wrote an opéra comique called Robinson Crusoé, which was first performed at the Opéra-Comique in Paris on 23 November 1867. This was based on the British pantomime version rather than the novel itself. The libretto was by Eugène Cormon and Hector-Jonathan Crémieux.

Bibliography

Bastian, F. Defoe's early life. Totowa, N.J.: Barnes & Noble, 1981.

Furbank, P. N. & W.R. Owens. A political biography of Daniel Defoe. London & Brookfield, Vt.: Pickering & Chatto, 2006.

Moore, John Robert. Daniel Defoe, Citizen of the Modern World. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1958.

Novak, Maximillian E, Daniel Defoe, Master of Fictions: His Life and Ideas. Oxford & New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

Richetti, John, The life of Daniel Defoe. Malden, MA & Oxford: Blackwell Pub., 2005.

Last modified 14 Febuary 2018